По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

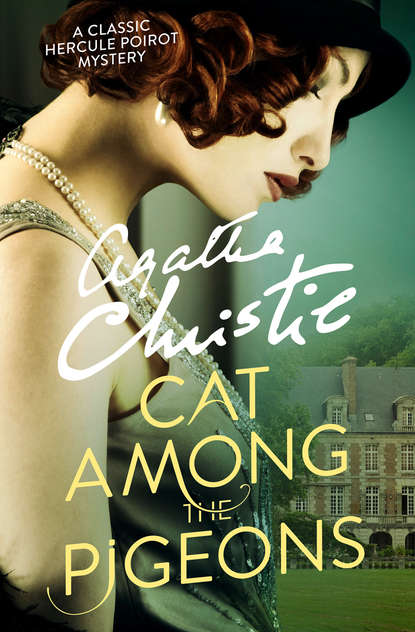

Cat Among the Pigeons

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Trying’s not enough. You have to succeed. Send me along Ronnie first. I’ve got an assignment for him.’

II

Colonel Pikeaway was apparently just going off to sleep again when the young man called Ronnie entered the room. He was tall, dark, muscular, and had a gay and rather impertinent manner.

Colonel Pikeaway looked at him for a moment or two and then grinned.

‘How’d you like to penetrate into a girls’ school?’ he asked.

‘A girls’ school?’ The young man lifted his eyebrows. ‘That will be something new! What are they up to? Making bombs in the chemistry class?’

‘Nothing of that kind. Very superior high-class school. Meadowbank.’

‘Meadowbank!’ the young man whistled. ‘I can’t believe it!’

‘Hold your impertinent tongue and listen to me. Princess Shaista, first cousin and only near relative of the late Prince Ali Yusuf of Ramat, goes there this next term. She’s been at school in Switzerland up to now.’

‘What do I do? Abduct her?’

‘Certainly not. I think it possible she may become a focus of interest in the near future. I want you to keep an eye on developments. I’ll have to leave it vague. I don’t know what or who may turn up, but if any of our more unlikeable friends seem to be interested, report it…A watching brief, that’s what you’ve got.’

The young man nodded.

‘And how do I get in to watch? Shall I be the drawing master?’

‘The visiting staff is all female.’ Colonel Pikeaway looked at him in a considering manner. ‘I think I’ll have to make you a gardener.’

‘A gardener?’

‘Yes. I’m right in thinking you know something about gardening?’

‘Yes, indeed. I ran a column on Your Garden in the Sunday Mail for a year in my younger days.’

‘Tush!’ said Colonel Pikeaway. ‘That’s nothing! I could do a column on gardening myself without knowing a thing about it—just crib from a few luridly illustrated Nurseryman’s catalogues and a Gardening Encyclopedia. I know all the patter. “Why not break away from tradition and sound a really tropical note in your border this year? Lovely Amabellis Gossiporia, and some of the wonderful new Chinese hybrids of Sinensis Maka foolia. Try the rich blushing beauty of a clump of Sinistra Hopaless, not very hardy but they should be all right against a west wall.”’ He broke off and grinned. ‘Nothing to it! The fools buy the things and early frost sets in and kills them and they wish they’d stuck to wallflowers and forget-me-nots! No, my boy, I mean the real stuff. Spit on your hands and use the spade, be well acquainted with the compost heap, mulch diligently, use the Dutch hoe and every other kind of hoe, trench really deep for your sweet peas—and all the rest of the beastly business. Can you do it?’

‘All these things I have done from my youth upwards!’

‘Of course you have. I know your mother. Well, that’s settled.’

‘Is there a job going as a gardener at Meadowbank?’

‘Sure to be,’ said Colonel Pikeaway. ‘Every garden in England is short staffed. I’ll write you some nice testimonials. You’ll see, they’ll simply jump at you. No time to waste, summer term begins on the 29th.’

‘I garden and I keep my eyes open, is that right?’

‘That’s it, and if any oversexed teenagers make passes at you, Heaven help you if you respond. I don’t want you thrown out on your ear too soon.’

He drew a sheet of paper towards him. ‘What do you fancy as a name?’

‘Adam would seem appropriate.’

‘Last name?’

‘How about Eden?’

‘I’m not sure I like the way your mind is running. Adam Goodman will do very nicely. Go and work out your past history with Jenson and then get cracking.’ He looked at his watch. ‘I’ve no more time for you. I don’t want to keep Mr Robinson waiting. He ought to be here by now.’

Adam (to give him his new name) stopped as he was moving to the door.

‘Mr Robinson?’ he asked curiously. ‘Is he coming?’

‘I said so.’ A buzzer went on the desk. ‘There he is now. Always punctual, Mr Robinson.’

‘Tell me,’ said Adam curiously. ‘Who is he really? What’s his real name?’

‘His name,’ said Colonel Pikeaway, ‘is Mr Robinson. That’s all I know, and that’s all anybody knows.’

III

The man who came into the room did not look as though his name was, or could ever have been, Robinson. It might have been Demetrius, or Isaacstein, or Perenna—though not one or the other in particular. He was not definitely Jewish, nor definitely Greek nor Portuguese nor Spanish, nor South American. What did seem highly unlikely was that he was an Englishman called Robinson. He was fat and well dressed, with a yellow face, melancholy dark eyes, a broad forehead, and a generous mouth that displayed rather over-large very white teeth. His hands were well shaped and beautifully kept. His voice was English with no trace of accent.

He and Colonel Pikeaway greeted each other rather in the manner of two reigning monarchs. Politenesses were exchanged.

Then, as Mr Robinson accepted a cigar, Colonel Pikeaway said:

‘It is very good of you to offer to help us.’

Mr Robinson lit his cigar, savoured it appreciatively, and finally spoke.

‘My dear fellow. I just thought—I hear things, you know. I know a lot of people, and they tell me things. I don’t know why.’

Colonel Pikeaway did not comment on the reason why.

He said:

‘I gather you’ve heard that Prince Ali Yusuf’s plane has been found?’

‘Wednesday of last week,’ said Mr Robinson. ‘Young Rawlinson was the pilot. A tricky flight. But the crash wasn’t due to an error on Rawlinson’s part. The plane had been tampered with—by a certain Achmed—senior mechanic. Completely trustworthy—or so Rawlinson thought. But he wasn’t. He’s got a very lucrative job with the new régime now.’

‘So it was sabotage! We didn’t know that for sure. It’s a sad story.’

‘Yes. That poor young man—Ali Yusuf, I mean—was ill equipped to cope with corruption and treachery. His public school education was unwise—or at least that is my view. But we do not concern ourselves with him now, do we? He is yesterday’s news. Nothing is so dead as a dead king. We are concerned, you in your way, I in mine, with what dead kings leave behind them.’

‘Which is?’

Mr Robinson shrugged his shoulders.

‘A substantial bank balance in Geneva, a modest balance in London, considerable assets in his own country now taken over by the glorious new régime (and a little bad feeling as to how the spoils have been divided, or so I hear!), and finally a small personal item.’