По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

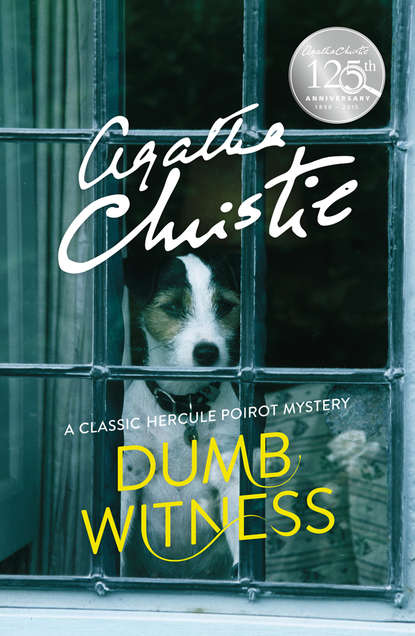

Dumb Witness

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What next?’ I asked.

The dog seemed to be asking the same question.

‘Parbleu, to Messrs—what is it—Messrs Gabler and Stretcher.’

‘That does seem indicated,’ I agreed.

We turned and retraced our steps, our canine acquaintance sending a few disgusted barks after us.

The premises of Messrs Gabler and Stretcher were situated in the Market Square. We entered a dim outer office where we were received by a young woman with adenoids and a lack-lustre eye.

‘Good morning,’ said Poirot politely.

The young woman was at the moment speaking into a telephone but she indicated a chair and Poirot sat down. I found another and brought it forward.

‘I couldn’t say, I’m sure,’ said the young woman into the telephone vacantly. ‘No, I don’t know what the rates would be… Pardon? Oh, main water, I think, but, of course, I couldn’t be certain… I’m very sorry, I’m sure… No, he’s out… No, I couldn’t say… Yes, of course I’ll ask him… Yes…8135? I’m afraid I haven’t quite got it. Oh…8935…39… Oh, 5135… Yes, I’ll ask him to ring you…after six… Oh, pardon, before six… Thank you so much.’

She replaced the receiver, scribbled 5319 on the blotting-pad and turned a mildly inquiring but uninterested gaze on Poirot.

Poirot began briskly.

‘I observe that there is a house to be sold just on the outskirts of this town. Littlegreen House, I think is the name.’

‘Pardon?’

‘A house to be let or sold,’ said Poirot slowly and distinctly. ‘Littlegreen House.’

‘Oh, Littlegreen House,’ said the young woman vaguely. ‘Littlegreen House, did you say?’

‘That is what I said.’

‘Littlegreen House,’ said the young woman, making a tremendous mental effort. ‘Oh, well, I expect Mr Gabler would know about that.’

‘Can I see Mr Gabler?’

‘He’s out,’ said the young woman with a kind of faint, anaemic satisfaction as of one who says, ‘A point to me.’

‘Do you know when he will be in?’

‘I couldn’t say, I’m sure,’ said the young woman.

‘You comprehend, I am looking for a house in this neighbourhood,’ said Poirot.

‘Oh, yes,’ said the young woman, uninterested.

‘And Littlegreen House seems to me just what I am looking for. Can you give me particulars?’

‘Particulars?’ The young woman seemed startled.

‘Particulars of Littlegreen House.’

Unwillingly she opened a drawer and took out an untidy file of papers.

Then she called, ‘John.’

A lanky youth sitting in a corner looked up.

‘Yes, miss.’

‘Have we got any particulars of—what did you say?’

‘Littlegreen House,’ said Poirot distinctly.

‘You’ve got a large bill of it here,’ I remarked, pointing to the wall.

She looked at me coldly. Two to one, she seemed to think, was an unfair way of playing the game. She called up her own reinforcements.

‘You don’t know anything about Littlegreen House, do you, John?’

‘No, miss. Should be in the file.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said the young woman without looking so in the least. ‘I rather fancy we must have sent all the particulars out.’

‘C’est dommage.’

‘Pardon?’

‘A pity.’

‘We’ve a nice bungalow at Hemel End, two bed., one sitt.’

She spoke without enthusiasm, but with the air of one willing to do her duty by her employer.

‘I thank you, no.’

‘And a semi-detached with small conservatory. I could give you particulars of that.’

‘No, thank you. I desired to know what rent you were asking for Littlegreen House.’

‘It’s not to be rented,’ said the young woman, abandoning her position of complete ignorance of anything to do with Littlegreen House in the pleasure of scoring a point. ‘Only to be sold outright.’

‘The board says, “To be Let or Sold.”’

‘I couldn’t say as to that, but it’s for sale only.’

At this stage in the battle the door opened and a grey-haired, middle-aged man entered with a rush. His eye, a militant one, swept over us with a gleam. His eyebrows asked a question of his employee.

‘This is Mr Gabler,’ said the young woman.