По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

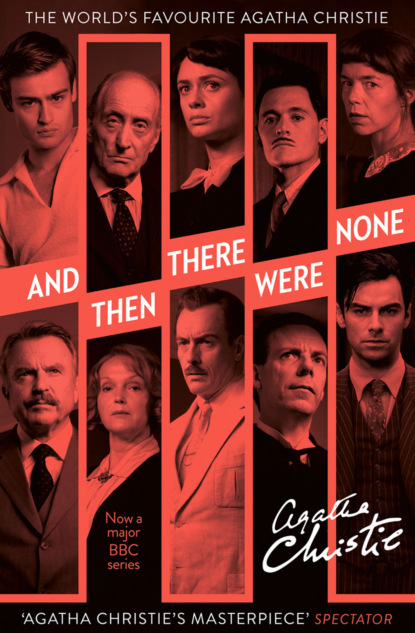

And Then There Were None

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Anthony Marston growled:

‘Don’t know what the damned fool was getting at!’

The upraised hand of Mr Justice Wargrave calmed the tumult.

He said, picking his words with care:

‘I wish to say this. Our unknown friend accuses me of the murder of one Edward Seton. I remember Seton perfectly well. He came up before me for trial in June of the year 1930. He was charged with the murder of an elderly woman. He was very ably defended and made a good impression on the jury in the witness-box. Nevertheless, on the evidence, he was certainly guilty. I summed up accordingly, and the jury brought in a verdict of Guilty. In passing sentence of death I concurred with the verdict. An appeal was lodged on the grounds of misdirection. The appeal was rejected and the man was duly executed. I wish to say before you all that my conscience is perfectly clear on the matter. I did my duty and nothing more. I passed sentence on a rightly convicted murderer.’

Armstrong was remembering now. The Seton case! The verdict had come as a great surprise. He had met Matthews, KC on one of the days of the trial dining at a restaurant. Matthews had been confident. ‘Not a doubt of the verdict. Acquittal practically certain.’ And then afterwards he had heard comments: ‘Judge was dead against him. Turned the jury right round and they brought him in guilty. Quite legal, though. Old Wargrave knows his law. It was almost as though he had a private down on the fellow.’

All these memories rushed through the doctor’s mind. Before he could consider the wisdom of the question he had asked impulsively:

‘Did you know Seton at all? I mean previous to the case.’

The hooded reptilian eyes met his. In a clear cold voice the judge said:

‘I knew nothing of Seton previous to the case.’

Armstrong said to himself:

‘The fellow’s lying—I know he’s lying.’

II

Vera Claythorne spoke in a trembling voice.

She said:

‘I’d like to tell you. About that child—Cyril Hamilton. I was nursery governess to him. He was forbidden to swim out far. One day, when my attention was distracted, he started off. I swam after him… I couldn’t get there in time… It was awful… But it wasn’t my fault. At the inquest the Coroner exonerated me. And his mother—she was so kind. If even she didn’t blame me, why should—why should this awful thing be said? It’s not fair—not fair…’

She broke down, weeping bitterly.

General Macarthur patted her shoulder.

He said:

‘There there, my dear. Of course it’s not true. Fellow’s a madman. A madman! Got a bee in his bonnet! Got hold of the wrong end of the stick all round.’

He stood erect, squaring his shoulders. He barked out:

‘Best really to leave this sort of thing unanswered. However, feel I ought to say—no truth—no truth whatever in what he said about—er—young Arthur Richmond. Richmond was one of my officers. I sent him on a reconnaissance. He was killed. Natural course of events in wartime. Wish to say resent very much—slur on my wife. Best woman in the world. Absolutely—Cæsar’s wife!’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: