По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

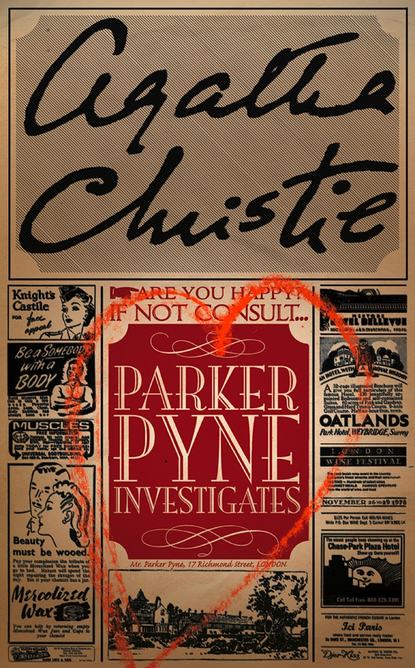

Parker Pyne Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Suddenly she felt alone, helpless, utterly forlorn. Slowly she took up the morning paper and read, not for the first time, an advertisement on the front page.

‘Absurd!’ said Mrs Packington. ‘Utterly absurd.’ Then: ‘After all, I might just see…’

Which explains why at eleven o’clock Mrs Packington, a little nervous, was being shown into Mr Parker Pyne’s private office.

As has been said, Mrs Packington was nervous, but somehow or other, the mere sight of Mr Parker Pyne brought a feeling of reassurance. He was large, not to say fat; he had a bald head of noble proportions, strong glasses, and little twinkling eyes.

‘Pray sit down,’ said Mr Parker Pyne. ‘You have come in answer to my advertisement?’ he added helpfully.

‘Yes,’ said Mrs Packington, and stopped there.

‘And you are not happy,’ said Mr Parker Pyne in a cheerful, matter-of-fact voice. ‘Very few people are. You would really be surprised if you knew how few people are happy.’

‘Indeed?’ said Mrs Packington, not feeling, however, that it mattered whether other people were unhappy or not.

‘Not interesting to you, I know,’ said Mr Parker Pyne, ‘but very interesting to me. You see, for thirty-five years of my life I have been engaged in the compiling of statistics in a government office. Now I have retired, and it has occurred to me to use the experience I have gained in a novel fashion. It is all so simple. Unhappiness can be classified under five main heads–no more, I assure you. Once you know the cause of a malady, the remedy should not be impossible.

‘I stand in the place of the doctor. The doctor first diagnoses the patient’s disorder, then he proceeds to recommend a course of treatment. There are cases where no treatment can be of avail. If that is so, I say frankly that I can do nothing. But I assure you, Mrs Packington, that if I undertake a case, the cure is practically guaranteed.’

Could it be so? Was this nonsense, or could it, perhaps be true? Mrs Packington gazed at him hopefully.

‘Shall we diagnose your case?’ said Mr Parker Pyne, smiling. He leaned back in his chair and brought the tips of his fingers together. ‘The trouble concerns your husband. You have had, on the whole, a happy married life. You husband has, I think, prospered. I think there is a young lady concerned in the case–perhaps a young lady in your husband’s office.’

‘A typist,’ said Mrs Packington. ‘A nasty made-up little minx, all lipstick and silk stockings and curls.’ The words rushed from her.

Mr Parker Pyne nodded in a soothing manner. ‘There is no real harm in it–that is your husband’s phrase, I have no doubt.’

‘His very words.’

‘Why, therefore, should he not enjoy a pure friendship with this young lady, and be able to bring a little brightness, a little pleasure, into her dull existence? Poor child, she has so little fun. Those, I imagine, are his sentiments.’

Mrs Packington nodded with vigour. ‘Humbug–all humbug! He takes her on the river–I’m fond of going on the river myself, but five or six years ago he said it interfered with his golf. But he can give up golf for her. I like the theatre–George has always said he’s too tired to go out at night. Now he takes her out to dance–dance! And comes back at three in the morning. I–I–’

‘And doubtless he deplores the fact that women are so jealous, so unreasonably jealous when there is absolutely no cause for jealousy?’

Again Mrs Packington nodded. ‘That’s it.’ She asked sharply: ‘How do you know all this?’

‘Statistics,’ Mr Parker Pyne said simply.

‘I’m so miserable,’ said Mrs Packington. ‘I’ve always been a good wife to George. I worked my fingers to the bone in our early days. I helped him to get on. I’ve never looked at any other man. His things are always mended, he gets good meals, and the house is well and economically run. And now that we’ve got on in the world and could enjoy ourselves and go about a bit and do all the things I’ve looked forward to doing some day–well, this!’ She swallowed hard.

Mr Parker Pyne nodded gravely. ‘I assure you I understand your case perfectly.’

‘And–can you do anything?’ She asked it almost in a whisper.

‘Certainly, my dear lady. There is a cure. Oh yes, there is a cure.’

‘What is it?’ She waited, round-eyed and expectant.

Mr Parker Pyne spoke quietly and firmly. ‘You will place yourself in my hands, and the fee will be two hundred guineas.’

‘Two hundred guineas!’

‘Exactly. You can afford to pay such a fee, Mrs Packington. You would pay that sum for an operation. Happiness is just as important as bodily health.’

‘I pay you afterwards, I suppose?’

‘On the contrary,’ said Mr Parker Pyne. ‘You pay me in advance.’

Mrs Packington rose. ‘I’m afraid I don’t see my way–’

‘To buying a pig in a poke?’ said Mr Parker Pyne cheerfully. ‘Well, perhaps you’re right. It’s a lot of money to risk. You’ve got to trust me, you see. You’ve got to pay the money and take a chance. Those are my terms.’

‘Two hundred guineas!’

‘Exactly. Two hundred guineas. It’s a lot of money. Good-morning, Mrs Packington. Let me know if you change your mind.’ He shook hands with her, smiling in an unperturbed fashion.

When she had gone he pressed a buzzer on his desk. A forbidding-looking young woman with spectacles answered it.

‘A file, please, Miss Lemon. And you might tell Claude that I am likely to want him shortly.’

‘A new client?’

‘A new client. At the moment she has jibbed, but she will come back. Probably this afternoon about four. Enter her.’

‘Schedule A?’

‘Schedule A, of course. Interesting how everyone thinks his own case unique. Well, well, warn Claude. Not too exotic, tell him. No scent and he’d better get his hair cut short.’

It was a quarter-past four when Mrs Packington once more entered Mr Parker Pyne’s office. She drew out a cheque book, made out a cheque and passed it to him. A receipt was given.

‘And now?’ Mrs Packington looked at him hopefully.

‘And now,’ said Mr Parker Pyne, smiling, ‘you will return home. By the first post tomorrow you will receive certain instructions which I shall be glad if you will carry out.’

Mrs Packington went home in a state of pleasant anticipation. Mr Packington came home in a defensive mood, ready to argue his position if the scene at the breakfast table was reopened. He was relieved, however, to find that his wife did not seem to be in a combative mood. She was unusually thoughtful.

George listened to the radio and wondered whether that dear child Nancy would allow him to give her a fur coat. She was very proud, he knew. He didn’t want to offend her. Still, she had complained of the cold. That tweed coat of hers was a cheap affair; it didn’t keep the cold out. He could put it so that she wouldn’t mind, perhaps…

They must have another evening out soon. It was a pleasure to take a girl like that to a smart restaurant. He could see several young fellows were envying him. She was uncommonly pretty. And she liked him. To her, as she had told him, he didn’t seem a bit old.

He looked up and caught his wife’s eye. He felt suddenly guilty, which annoyed him. What a narrow-minded, suspicious woman Maria was! She grudged him any little bit of happiness.

He switched off the radio and went to bed.

Mrs Packington received two unexpected letters the following morning. One was a printed form confirming an appointment at a noted beauty specialist’s. The second was an appointment with a dressmaker. The third was from Mr Parker Pyne, requesting the pleasure of her company at lunch at the Ritz that day.

Mr Packington mentioned that he might not be home to dinner that evening as he had to see a man on business. Mrs Packington merely nodded absently, and Mr Packington left the house congratulating himself on having escaped the storm.