По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

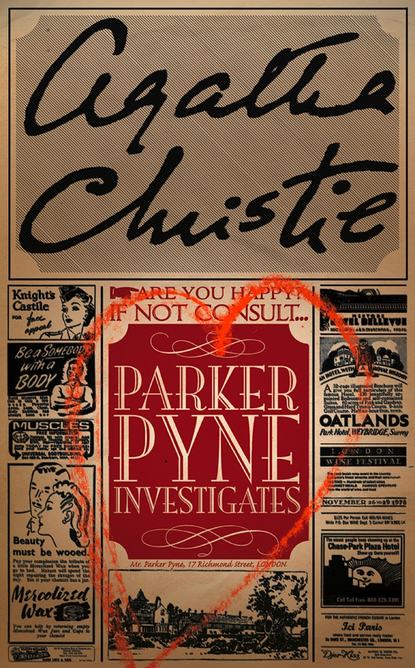

Parker Pyne Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The beauty specialist was impressive. Such neglect! Madame, but why? This should have been taken in hand years ago. However, it was not too late.

Things were done to her face; it was pressed and kneaded and steamed. It had mud applied to it. It had creams applied to it. It was dusted with powder. There were various finishing touches.

At last she was given a mirror. ‘I believe I do look younger,’ she thought to herself.

The dressmaking seance was equally exciting. She emerged feeling smart, modish, up-to-date.

At half-past one, Mrs Packington kept her appointment at the Ritz. Mr Parker Pyne, faultlessly dressed and carrying with him his atmosphere of soothing reassurance, was waiting for her.

‘Charming,’ he said, an experienced eye sweeping her from head to foot. ‘I have ventured to order you a White Lady.’

Mrs Packington, who had not contracted the cocktail habit, made no demur. As she sipped the exciting fluid gingerly, she listened to her benevolent instructor.

‘Your husband, Mrs Packington,’ said Mr Parker Pyne, ‘must be made to Sit Up. You understand–to Sit Up. To assist in that, I am going to introduce to you a young friend of mine. You will lunch with him today.’

At that moment a young man came along, looking from side to side. He espied Mr Parker Pyne and came gracefully towards them.

‘Mr Claude Luttrell, Mrs Packington.’

Mr Claude Luttrell was perhaps just short of thirty. He was graceful, debonair, perfectly dressed, extremely handsome.

‘Delighted to meet you,’ he murmured.

Three minutes later Mrs Packington was facing her new mentor at a small table for two.

She was shy at first, but Mr Luttrell soon put her at her ease. He knew Paris well and had spent a good deal of time on the Riviera. He asked Mrs Packington if she were fond of dancing. Mrs Packington said she was, but that she seldom got any dancing nowadays as Mr Packington didn’t care to go out in the evenings.

‘But he couldn’t be so unkind as to keep you at home,’ said Claude Luttrell, smiling and displaying a dazzling row of teeth. ‘Women will not tolerate male jealousy in these days.’

Mrs Packington nearly said that jealousy didn’t enter into the question. But the words remained unspoken. After all, it was an agreeable idea.

Claude Luttrell spoke airily of night clubs. It was settled that on the following evening Mrs Packington and Mr Luttrell should patronize the popular Lesser Archangel.

Mrs Packington was a little nervous about announcing this fact to her husband. George, she felt, would think it extraordinary and possibly ridiculous. But she was saved all trouble on this score. She had been too nervous to make her announcement at breakfast, and at two o’clock a telephone message came to the effect that Mr Packington would be dining in town.

The evening was a great success. Mrs Packington had been a good dancer as a girl and under Claude Luttrell’s skilled guidance she soon picked up modern steps. He congratulated her on her gown and also on the arrangement of her hair. (An appointment had been made for her that morning with a fashionable hairdresser.) On bidding her farewell, he kissed her hand in a most thrilling manner. Mrs Packington had not enjoyed an evening so much for years.

A bewildering ten days ensued. Mrs Packington lunched, teaed, tangoed, dined, danced and supped. She heard all about Claude Luttrell’s sad childhood. She heard the sad circumstances in which his father lost all his money. She heard of his tragic romance and his embittered feelings towards women generally.

On the eleventh day they were dancing at the Red Admiral. Mrs Packington saw her spouse before he saw her. George was with the young lady from his office. Both couples were dancing.

‘Hallo, George,’ said Mrs Packington lightly, as their orbits brought them together.

It was with considerable amusement that she saw her husband’s face grow first red, then purple with astonishment. With the astonishment was blended an expression of guilt detected.

Mrs Packington felt amusedly mistress of the situation. Poor old George! Seated once more at her table, she watched them. How stout he was, how bald, how terribly he bounced on his feet! He danced in the style of twenty years ago. Poor George, how terribly he wanted to be young! And that poor girl he was dancing with had to pretend to like it. She looked bored enough now, her face over his shoulder where he couldn’t see it.

How much more enviable, thought Mrs Packington contentedly, was her own situation. She glanced at the perfect Claude, now tactfully silent. How well he understood her. He never jarred–as husbands so inevitably did jar after a lapse of years.

She looked at him again. Their eyes met. He smiled; his beautiful dark eyes, so melancholy, so romantic, looked tenderly into hers.

‘Shall we dance again?’ he murmured.

They danced again. It was heaven!

She was conscious of George’s apologetic gaze following them. It had been the idea, she remembered, to make George jealous. What a long time ago that was! She really didn’t want George to be jealous now. It might upset him. Why should he be upset, poor thing? Everyone was so happy…

Mr Packington had been home an hour when Mrs Packington got in. He looked bewildered and unsure of himself.

‘Humph,’ he remarked. ‘So you’re back.’

Mrs Packington cast off an evening wrap which had cost her forty guineas that very morning. ‘Yes,’ she said, smiling. ‘I’m back.’

George coughed. ‘Er–rather odd meeting you.’

‘Wasn’t it?’ said Mrs Packington.

‘I–well, I thought it would be a kindness to take that girl somewhere. She’s been having a lot of trouble at home. I thought–well, kindness, you know.’

Mrs Packington nodded. Poor old George–bouncing on his feet and getting so hot and being so pleased with himself.

‘Who’s that chap you were with? I don’t know him, do I?’

‘Luttrell, his name is. Claude Luttrell.’

‘How did you come across him?’

‘Oh, someone introduced me,’ said Mrs Packington vaguely.

‘Rather a queer thing for you to go out dancing–at your time of life. Musn’t make a fool of yourself, my dear.’

Mrs Packington smiled. She was feeling much too kindly to the universe in general to make the obvious reply. ‘A change is always nice,’ she said amiably.

‘You’ve got to be careful, you know. A lot of these lounge-lizard fellows going about. Middle-aged women sometimes make awful fools of themselves. I’m just warning you, my dear. I don’t like to see you doing anything unsuitable.’

‘I find the exercise very beneficial,’ said Mrs Packington.

‘Um–yes.’

‘I expect you do, too,’ said Mrs Packington kindly. ‘The great thing is to be happy, isn’t it? I remember your saying so one morning at breakfast, about ten days ago.’

Her husband looked at her sharply, but her expression was devoid of sarcasm. She yawned.

‘I must go to bed. By the way, George, I’ve been dreadfully extravagant lately. Some terrible bills will be coming in. You don’t mind, do you?’

‘Bills?’ said Mr Packington.

‘Yes. For clothes. And massage. And hair treatment. Wickedly extravagant I’ve been–but I know you don’t mind.’