По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

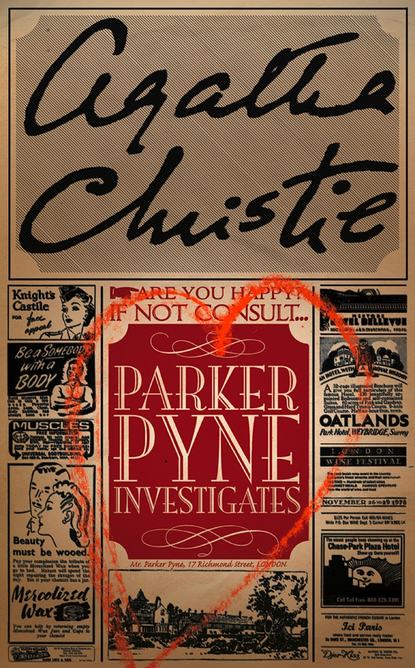

Parker Pyne Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I do indeed. The question is, what shall we do next? You don’t want to go to the police, I suppose?’

‘Oh, no, please.’

‘I’m glad you say that. I don’t see what good the police could do, and it would only mean unpleasantness for you. Now I suggest that you allow me to give you lunch somewhere and that I then accompany you back to your lodgings, so as to be sure you reach them safely. And then, we might have a look for the paper. Because, you know, it must be somewhere.’

‘Father may have destroyed it himself.’

‘He may, of course, but the other side evidently doesn’t think so, and that looks hopeful for us.’

‘What do you think it can be? Hidden treasure?’

‘By jove, it might be!’ exclaimed Major Wilbraham, all the boy in him rising joyfully to the suggestion. ‘But now, Miss Clegg, lunch!’

They had a pleasant meal together. Wilbraham told Freda all about his life in East Africa. He described elephant hunts, and the girl was thrilled. When they had finished, he insisted on taking her home in a taxi.

Her lodgings were near Notting Hill Gate. On arriving there, Freda had a brief conversation with her landlady. She returned to Wilbraham and took him up to the second floor, where she had a tiny bedroom and sitting-room.

‘It’s exactly as we thought,’ she said. ‘A man came on Saturday morning to see about laying a new electric cable; he told her there was a fault in the wiring in my room. He was there some time.’

‘Show me this chest of your father’s,’ said Wilbraham.

Freda showed him a brass-bound box. ‘You see,’ she said, raising the lid, ‘it’s empty.’

The soldier nodded thoughtfully. ‘And there are no papers anywhere else?’

‘I’m sure there aren’t. Mother kept everything in here.’

Wilbraham examined the inside of the chest. Suddenly he uttered an exclamation. ‘Here’s a slit in the lining.’ Carefully he inserted his hand, feeling about. A slight crackle rewarded him. ‘Something’s slipped down behind.’

In another minute he had drawn out his find. A piece of dirty paper folded several times. He smoothed it out on the table; Freda was looking over his shoulder. She uttered an exclamation of disappointment.

‘It’s just a lot of queer marks.’

‘Why, the thing’s in Swahili. Swahili, of all things!’ cried Major Wilbraham. ‘East African native dialect, you know.’

‘How extraordinary!’ said Freda. ‘Can you read it, then?’

‘Rather. But what an amazing thing.’ He took the paper to the window.

‘Is it anything?’ asked Freda tremulously. Wilbraham read the thing through twice, and then came back to the girl. ‘Well,’ he said, with a chuckle, ‘here’s your hidden treasure, all right.’

‘Hidden treasure? Not really? You mean Spanish gold–a sunken galleon–that sort of thing?’

‘Not quite so romantic as that, perhaps. But it comes to the same thing. This paper gives the hiding-place of a cache of ivory.’

‘Ivory?’ said the girl, astonished.

‘Yes. Elephants, you know. There’s a law about the number you’re allowed to shoot. Some hunter got away with breaking that law on a grand scale. They were on his trail and he cached the stuff. There’s a thundering lot of it–and this gives fairly clear directions how to find it. Look here, we’ll have to go after this, you and I.’

‘You mean there’s really a lot of money in it?’

‘Quite a nice little fortune for you.’

‘But how did that paper come to be among my father’s things?’

Wilbraham shrugged. ‘Maybe the Johnny was dying or something. He may have written the thing down in Swahili for protection and given it to your father, who possibly had befriended him in some way. Your father, not being able to read it, attached no importance to it. That’s only a guess on my part, but I dare say it’s not far wrong.’

Freda gave a sigh. ‘How frightfully exciting!’

‘The thing is–what to do with the precious document,’ said Wilbraham. ‘I don’t like leaving it here. They might come and have another look. I suppose you wouldn’t entrust it to me?’

‘Of course I would. But–mightn’t it be dangerous for you?’ she faltered.

‘I’m a tough nut,’ said Wilbraham grimly. ‘You needn’t worry about me.’ He folded up the paper and put it in his pocket-book. ‘May I come to see you tomorrow evening?’ he asked. ‘I’ll have worked out a plan by then, and I’ll look up the places on my map. What time do you get back from the city?’

‘I get back about half-past six.’

‘Capital. We’ll have a powwow and then perhaps you’ll let me take you out to dinner. We ought to celebrate. So long, then. Tomorrow at half-past six.’

Major Wilbraham arrived punctually on the following day. He rang the bell and enquired for Miss Clegg. A maid-servant had answered the door.

‘Miss Clegg? She’s out.’

‘Oh!’ Wilbraham did not like to suggest that he come in and wait. ‘I’ll call back presently,’ he said.

He hung about in the street opposite, expecting every minute to see Freda tripping towards him. The minutes passed. Quarter to seven. Seven. Quarter-past seven. Still no Freda. A feeling of uneasiness swept over him. He went back to the house and rang the bell again.

‘Look here,’ he said, ‘I had an appointment with Miss Clegg at half-past six. Are you sure she isn’t in or hasn’t–er–left any message?’

‘Are you Major Wilbraham?’ asked the servant.

‘Yes.’

‘Then there’s a note for you. It come by hand.’

Dear Major Wilbraham,–Something rather strange has happened. I won’t write more now, but will you meet me at Whitefriars? Go there as soon as you get this.

Yours sincerely,

Freda Clegg

Wilbraham drew his brows together as he thought rapidly. His hand drew a letter absent-mindedly from his pocket. It was to his tailor. ‘I wonder,’ he said to the maid-servant, ‘if you could let me have a stamp.’

‘I expect Mrs Parkins could oblige you.’

She returned in a moment with the stamp. It was paid for with a shilling. In another minute Wilbraham was walking towards the tube station, dropping the envelope in a box as he passed.

Freda’s letter had made him most uneasy. What could have taken the girl, alone, to the scene of yesterday’s sinister encounter?