По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

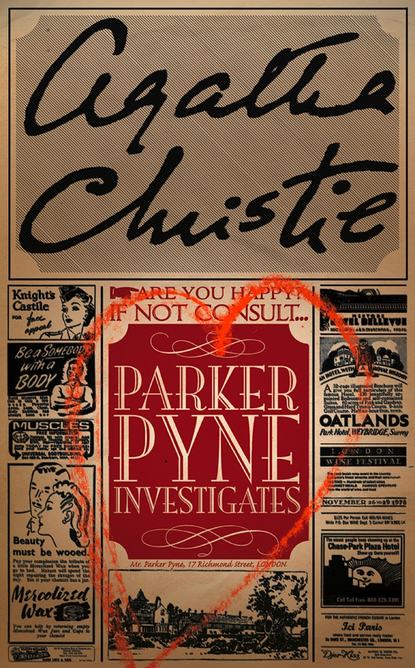

Parker Pyne Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘A bit more difficult, this,’ said Wilbraham. ‘Hallo, here’s a piece of luck. It’s unlocked.’

He pushed it open, peered round it, then beckoned the girl to come on. They emerged into a passage behind the kitchen. In another moment they were standing under the stars in Friars Lane.

‘Oh!’ Freda gave a little sob. ‘Oh, how dreadful it’s been!’

‘My poor darling.’ He caught her in his arms. ‘You’ve been so wonderfully brave. Freda–darling angel–could you ever–I mean, would you–I love you, Freda. Will you marry me?’

After a suitable interval, highly satisfactory to both parties, Major Wilbraham said, with a chuckle:

‘And what’s more, we’ve still got the secret of the ivory cache.’

‘But they took it from you!’

The major chuckled again. ‘That’s just what they didn’t do! You see, I wrote out a spoof copy, and before joining you here tonight, I put the real thing in a letter I was sending to my tailor and posted it. They’ve got the spoof copy–and I wish them joy of it! Do you know what we’ll do, sweetheart! We’ll go to East Africa for our honeymoon and hunt out the cache.’

III

Mr Parker Pyne left his office and climbed two flights of stairs. Here in a room at the top of the house sat Mrs Oliver, the sensational novelist, now a member of Mr Pyne’s staff.

Mr Parker Pyne tapped at the door and entered. Mrs Oliver sat at a table on which were a typewriter, several notebooks, a general confusion of loose manuscripts and a large bag of apples.

‘A very good story, Mrs Oliver,’ said Mr Parker Pyne genially.

‘It went off well?’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘I’m glad.’

‘That water-in-the-cellar business,’ said Mr Parker Pyne. ‘You don’t think, on a future occasion, that something more original–perhaps?’ He made the suggestion with proper diffidence.

Mrs Oliver shook her head and took an apple from her bag. ‘I think not, Mr Pyne. You see, people are used to reading about such things. Water rising in a cellar, poison gas, et cetera. Knowing about it beforehand gives it an extra thrill when it happens to oneself. The public is conservative, Mr Pyne; it likes the old well-worn gadgets.’

‘Well, you should know,’ admitted Mr Parker Pyne, mindful of the authoress’s forty-six successful works of fiction, all best sellers in England and America, and freely translated into French, German, Italian, Hungarian, Finnish, Japanese and Abyssinian. ‘How about expenses?’

Mrs Oliver drew a paper towards her. ‘Very moderate, on the whole. The two darkies, Percy and Jerry, wanted very little. Young Lorrimer, the actor, was willing to enact the part of Mr Reid for five guineas. The cellar speech was a phonograph record, of course.’

‘Whitefriars has been extremely useful to me,’ said Mr Pyne. ‘I bought it for a song and it has already been the scene of eleven exciting dramas.’

‘Oh, I forgot,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘Johnny’s wages. Five shillings.’

‘Johnny?’

‘Yes. The boy who poured the water from the watering cans through the hole in the wall.’

‘Ah yes. By the way, Mrs Oliver, how did you happen to know Swahili?’

‘I didn’t.’

‘I see. The British Museum perhaps?’

‘No. Delfridge’s Information Bureau.’

‘How marvellous are the resources of modern commerce!’ he murmured.

‘The only thing that worries me,’ said Mrs Oliver, ‘is that those two young people won’t find any cache when they get there.’

‘One cannot have everything in this world,’ said Mr Parker Pyne. ‘They will have had a honeymoon.’

Mrs Wilbraham was sitting in a deck-chair. Her husband was writing a letter. ‘What’s the date, Freda?’

‘The sixteenth.’

‘The sixteenth. By jove!’

‘What is it, dear?’

‘Nothing. I just remembered a chap named Jones.’

However happily married, there are some things one never tells.

‘Dash it all,’ thought Major Wilbraham. ‘I ought to have called at that place and got my money back.’ And then, being a fair-minded man, he looked at the other side of the question. ‘After all, it was I who broke the bargain. I suppose if I’d gone to see Jones something would have happened. And, anyway, as it turns out, if I hadn’t been going to see Jones, I should never have heard Freda cry for help, and we might never have met. So, indirectly, perhaps they have a right to the fifty pounds!’

Mrs Wilbraham was also following out a train of thought. ‘What a silly little fool I was to believe in that advertisement and pay those people three guineas. Of course, they never did anything for it and nothing ever happened. If I’d only known what was coming–first Mr Reid, and then the queer, romantic way that Charlie came into my life. And to think that but for pure chance I might never have met him!’

She turned and smiled adoringly at her husband.

The Case of the Distressed Lady

I

The buzzer on Mr Parker Pyne’s desk purred discreetly. ‘Yes?’ said the great man.

‘A young lady wishes to see you,’ announced his secretary. ‘She has no appointment.’

‘You may send her in, Miss Lemon.’ A moment later he was shaking hands with his visitor. ‘Good-morning,’ he said. ‘Do sit down.’

The girl sat down and looked at Mr Parker Pyne. She was a pretty girl and quite young. Her hair was dark and wavy with a row of curls at the nape of the neck. She was beautifully turned out from the white knitted cap on her head to the cobweb stockings and dainty shoes. Clearly she was nervous.

‘You are Mr Parker Pyne?’ she asked.

‘I am.’

‘The one who–advertises?’

‘The one who advertises.’

‘You say that if people aren’t–aren’t happy–to–to come to you.’ ‘Yes.’

She took the plunge. ‘Well, I’m frightfully unhappy. So I thought I’d come along and just–and just see.’

Mr Parker Pyne waited. He felt there was more to come.