По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

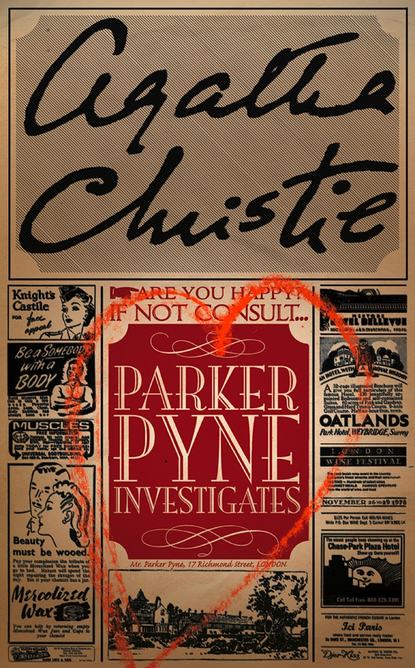

Parker Pyne Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Which means that we shall have to act quickly,’ said Mr Pyne thoughtfully. ‘It means gaining admission to the house–and if possible not in any menial capacity. Servants have little chance of handling valuable rings. Have you any ideas yourself, Mrs St John?’

‘Well, Naomi is giving a big party on Wednesday. And this friend of mine mentioned that she had been looking for some exhibition dancers. I don’t know if anything has been settled–’

‘I think it can be managed,’ said Mr Parker Pyne. ‘If the matter is already settled it will be more expensive, that is all. One thing more, do you happen to know where the main light switch is situated?’

‘As it happens I do know that, because a fuse blew out late one night when the servants had all gone to bed. It’s a box at the back of the hall–inside a little cupboard.’

At Mr Parker Pyne’s request she drew him a sketch.

‘And now,’ said Mr Parker Pyne, ‘everything is going to be all right, so don’t worry, Mrs St John. What about the ring? Shall I take it now, or would you rather keep it till Wednesday?’

‘Well, perhaps I’d better keep it.’

‘Now, no more worry, mind you,’ Mr Parker Pyne admonished her.

‘And your–fee?’ she asked timidly.

‘That can stand over for the moment. I will let you know on Wednesday what expenses have been necessary. The fee will be nominal, I assure you.’

He conducted her to the door, then rang the buzzer on his desk.

‘Send Claude and Madeleine here.’

Claude Luttrell was one of the handsomest specimens of lounge lizard to be found in England. Madeleine de Sara was the most seductive of vamps.

Mr Parker Pyne surveyed them with approval. ‘My children,’ he said, ‘I have a job for you. You are going to be internationally famous exhibition dancers. Now, attend to this carefully, Claude, and mind you get it right…’

II

Lady Dortheimer was fully satisfied with the arrangements for her ball. She surveyed the floral decorations and approved, gave a few last orders to the butler, and remarked to her husband that so far nothing had gone wrong!

It was a slight disappointment that Michael and Juanita, the dancers from the Red Admiral, had been unable to fulfil their contract at the last moment, owing to Juanita’s spraining her ankle, but instead, two new dancers were being sent (so ran the story over the telephone) who had created a furore in Paris.

The dancers duly arrived and Lady Dortheimer approved. The evening went splendidly. Jules and Sanchia did their turn, and most sensational it was. A wild Spanish Revolution dance. Then a dance called the Degenerate’s Dream. Then an exquisite exhibition of modern dancing.

The “cabaret” over, normal dancing was resumed. The handsome Jules requested a dance with Lady Dortheimer. They floated away. Never had Lady Dortheimer had such a perfect partner.

Sir Reuben was searching for the seductive Sanchia–in vain. She was not in the ballroom.

She was, as a matter of fact, out in the deserted hall near a small box, with her eyes fixed on the jewelled watch which she wore round her wrist.

‘You are not English–you cannot be English–to dance as you do,’ murmured Jules into Lady Dortheimer’s ear. ‘You are the sprite, the spirit of the wind. Droushcka petrovka navarouchi.’

‘What is that language?’

‘Russian,’ said Jules mendaciously. ‘I say something to you in Russian that I dare not say in English.’

Lady Dortheimer closed her eyes. Jules pressed her closer to him.

Suddenly the lights went out. In the darkness Jules bent and kissed the hand that lay on his shoulder. As she made to draw it away, he caught it, raised it to his lips again. Somehow a ring slipped from her finger into his hand.

To Lady Dortheimer it seemed only a second before the lights went on again. Jules was smiling at her.

‘Your ring,’ he said. ‘It slipped off. You permit?’ He replaced it on her finger. His eyes said a number of things while he was doing it.

Sir Reuben was talking about the main switch. ‘Some idiot. Practical joke, I suppose.’

Lady Dortheimer was not interested. Those few minutes of darkness had been very pleasant.

III

Mr Parker Pyne arrived at his office on Thursday morning to find Mrs St John already awaiting him.

‘Show her in,’ said Mr Pyne.

‘Well?’ She was all eagerness.

‘You look pale,’ he said accusingly.

She shook her head. ‘I couldn’t sleep last night. I was wondering–’

‘Now, here is the little bill for expenses. Train fares, costumes, and fifty pounds to Michael and Juanita. Sixty-five pounds, seventeen shillings.’

‘Yes, yes! But about last night–was it all right? Did it happen?’

Mr Parker Pyne looked at her in surprise. ‘My dear young lady, naturally it is all right. I took it for granted that you understood that.’

‘What a relief! I was afraid–’

Mr Parker Pyne shook his head reproachfully. ‘Failure is a word not tolerated in this establishment. If I do not think I can succeed I refuse to undertake a case. If I do take a case, its success is practically a foregone conclusion.’

‘She’s really got her ring back and suspects nothing?’

‘Nothing whatever. The operation was most delicately conducted.’

Daphne St John sighed. ‘You don’t know the load off my mind. What were you saying about expenses?’

‘Sixty-five pounds, seventeen shillings.’

Mrs St John opened her bag and counted out the money. Mr Parker Pyne thanked her and wrote out a receipt.

‘But your fee?’ murmured Daphne. ‘This is only for expenses.’

‘In this case there is no fee.’

‘Oh, Mr Pyne! I couldn’t, really!’

‘My dear young lady, I insist. I will not touch a penny. It would be against my principles. Here is your receipt. And now–’