По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

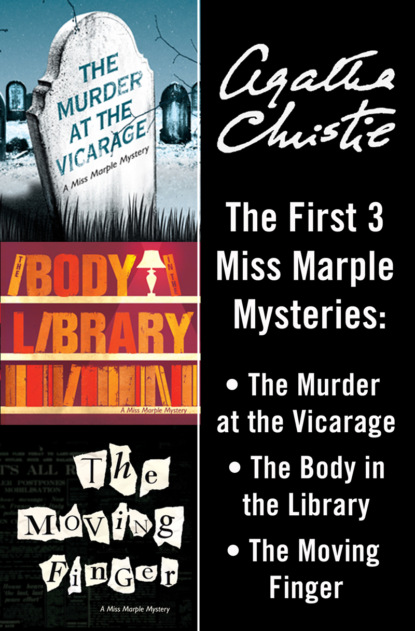

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Just what I feel myself,’ I said.

‘Well, then, sir, what about the lady who called on Colonel Protheroe the night before the murder?’

‘Mrs Lestrange,’ I cried, speaking rather loud in my astonishment.

The Inspector threw me a reproachful glance.

‘Not so loud, sir. Mrs Lestrange is the lady I’ve got my eye on. You remember what I told you – blackmail.’

‘Hardly a reason for murder. Wouldn’t it be a case of killing the goose that laid the golden eggs? That is, assuming that your hypothesis is true, which I don’t for a minute admit.’

The Inspector winked at me in a common manner.

‘Ah! She’s the kind the gentlemen will always stand up for. Now look here, sir. Suppose she’s successfully blackmailed the old gentleman in the past. After a lapse of years, she gets wind of him, comes down here and tries it on again. But, in the meantime, things have changed. The law has taken up a very different stand. Every facility is given nowadays to people prosecuting for blackmail – names are not allowed to be reported in the press. Suppose Colonel Protheroe turns round and says he’ll have the law on her. She’s in a nasty position. They give a very severe sentence for blackmail. The boot’s on the other leg. The only thing to do to save herself is to put him out good and quick.’

I was silent. I had to admit that the case the Inspector had built up was plausible. Only one thing to my mind made it inadmissible – the personality of Mrs Lestrange.

‘I don’t agree with you, Inspector,’ I said. ‘Mrs Lestrange doesn’t seem to me to be a potential blackmailer. She’s – well, it’s an old-fashioned word, but she’s a – lady.’

He threw me a pitying glance.

‘Ah! well, sir,’ he said tolerantly, ‘you’re a clergyman. You don’t know half of what goes on. Lady indeed! You’d be surprised if you knew some of the things I know.’

‘I’m not referring to mere social position. Anyway, I should imagine Mrs Lestrange to be a déclassée. What I mean is a question of – personal refinement.’

‘You don’t see her with the same eyes as I do, sir. I may be a man – but I’m a police officer, too. They can’t get over me with their personal refinement. Why, that woman is the kind who could stick a knife into you without turning a hair.’

Curiously enough, I could believe Mrs Lestrange guilty of murder much more easily than I could believe her capable of blackmail.

‘But, of course, she can’t have been telephoning to the old lady next door and shooting Colonel Protheroe at one and the same time,’ continued the Inspector.

The words were hardly out of his mouth when he slapped his leg ferociously.

‘Got it,’ he exclaimed. ‘That’s the point of the telephone call. Kind of alibi. Knew we’d connect it with the first one. I’m going to look into this. She may have bribed some village lad to do the phoning for her. He’d never think of connecting it with the murder.’

The Inspector hurried off.

‘Miss Marple wants to see you,’ said Griselda, putting her head in. ‘She sent over a very incoherent note – all spidery and underlined. I couldn’t read most of it. Apparently she can’t leave home herself. Hurry up and go across and see her and find out what it is. I’ve got my old women coming in two minutes or I’d come myself. I do hate old women – they tell you about their bad legs and sometimes insist on showing them to you. What luck that the inquest is this afternoon! You won’t have to go and watch the Boys’ Club Cricket Match.’

I hurried off, considerably exercised in my mind as to the reason for this summons.

I found Miss Marple in what, I believe, is described as a fluster. She was very pink and slightly incoherent.

‘My nephew,’ she explained. ‘My nephew, Raymond West, the author. He is coming down today. Such a to-do. I have to see to everything myself. You cannot trust a maid to air a bed properly, and we must, of course, have a meat meal tonight. Gentlemen require such a lot of meat, do they not? And drink. There certainly should be some drink in the house – and a siphon.’

‘If I can do anything –’ I began.

‘Oh! How very kind. But I did not mean that. There is plenty of time really. He brings his own pipe and tobacco, I am glad to say. Glad because it saves me from knowing which kind of cigarettes are right to buy. But rather sorry, too, because it takes so long for the smell to get out of the curtains. Of course, I open the window and shake them well very early every morning. Raymond gets up very late – I think writers often do. He writes very clever books, I believe, though people are not really nearly so unpleasant as he makes out. Clever young men know so little of life, don’t you think?’

‘Would you like to bring him to dinner at the Vicarage?’ I asked, still unable to gather why I had been summoned.

‘Oh! No, thank you,’ said Miss Marple. ‘It’s very kind of you,’ she added.

‘There was – er – something you wanted to see me about, I think,’ I suggested desperately.

‘Oh! Of course. In all the excitement it had gone right out of my head.’ She broke off and called to her maid. ‘Emily – Emily. Not those sheets. The frilled ones with the monogram, and don’t put them too near the fire.’

She closed the door and returned to me on tiptoe.

‘It’s just rather a curious thing that happened last night,’ she explained. ‘I thought you would like to hear about it, though at the moment it doesn’t seem to make sense. I felt very wakeful last night – wondering about all this sad business. And I got up and looked out of my window. And what do you think I saw?’

I looked, inquiring.

‘Gladys Cram,’ said Miss Marple, with great emphasis. ‘As I live, going into the wood with a suitcase.’

‘A suitcase?’

‘Isn’t it extraordinary? What should she want with a suitcase in the wood at twelve o’clock at night?

‘You see,’ said Miss Marple, ‘I dare say it has nothing to do with the murder. But it is a Peculiar Thing. And just at present we all feel we must take notice of Peculiar Things.’

‘Perfectly amazing,’ I said. ‘Was she going to – er – sleep in the barrow by any chance?’

‘She didn’t, at any rate,’ said Miss Marple. ‘Because quite a short time afterwards she came back, and she hadn’t got the suitcase with her.’

Chapter 18 (#ulink_782c7d88-a148-517c-839f-733741a42f0b)

The inquest was held that afternoon (Saturday) at two o’clock at the Blue Boar. The local excitement was, I need hardly say, tremendous. There had been no murder in St Mary Mead for at least fifteen years. And to have someone like Colonel Protheroe murdered actually in the Vicarage study is such a feast of sensation as rarely falls to the lot of a village population.

Various comments floated to my ears which I was probably not meant to hear.

‘There’s Vicar. Looks pale, don’t he? I wonder if he had a hand in it. ’Twas done at Vicarage, after all.’

‘How can you, Mary Adams? And him visiting Henry Abbott at the time.’ ‘Oh! But they do say him and the Colonel had words. There’s Mary Hill. Giving herself airs, she is, on account of being in service there. Hush, here’s coroner.’

The coroner was Dr Roberts of our adjoining town of Much Benham. He cleared his throat, adjusted his eyeglasses, and looked important.

To recapitulate all the evidence would be merely tiresome. Lawrence Redding gave evidence of finding the body, and identified the pistol as belonging to him. To the best of his belief he had seen it on the Tuesday, two days previously. It was kept on a shelf in his cottage, and the door of the cottage was habitually unlocked.

Mrs Protheroe gave evidence that she had last seen her husband at about a quarter to six when they separated in the village street. She agreed to call for him at the Vicarage later. She had gone to the Vicarage about a quarter past six, by way of the back lane and the garden gate. She had heard no voices in the study and had imagined that the room was empty, but her husband might have been sitting at the writing-table, in which case she would not have seen him. As far as she knew, he had been in his usual health and spirits. She knew of no enemy who might have had a grudge against him.

I gave evidence next, told of my appointment with Protheroe and my summons to the Abbotts’. I described how I had found the body and my summoning of Dr Haydock.

‘How many people, Mr Clement, were aware that Colonel Protheroe was coming to see you that evening?’

‘A good many, I should imagine. My wife knew, and my nephew, and Colonel Protheroe himself alluded to the fact that morning when I met him in the village. I should think several people might have overheard him, as, being slightly deaf, he spoke in a loud voice.’

‘It was, then, a matter of common knowledge? Anyone might know?’