По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

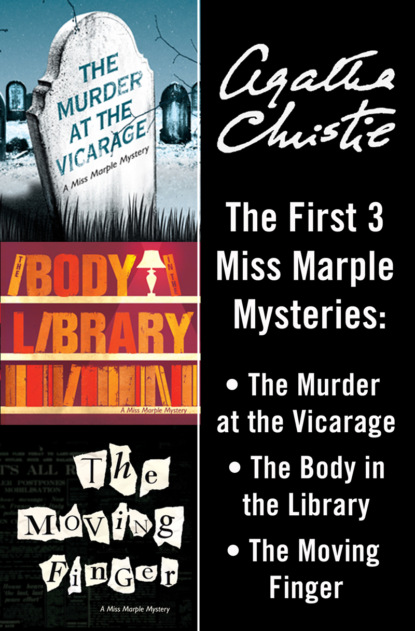

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I agreed.

Haydock followed. He was an important witness. He described carefully and technically the appearance of the body and the exact injuries. It was his opinion that the deceased had been shot at approximately 6.20 to 6.30 – certainly not later than 6.35. That was the outside limit. He was positive and emphatic on that point. There was no question of suicide, the wound could not have been self-inflicted.

Inspector Slack’s evidence was discreet and abridged. He described his summons and the circumstances under which he had found the body. The unfinished letter was produced and the time on it – 6.20 – noted. Also the clock. It was tacitly assumed that the time of death was 6.22. The police were giving nothing away. Anne Protheroe told me afterwards that she had been told to suggest a slightly earlier period of time than 6.20 for her visit.

Our maid, Mary, was the next witness, and proved a somewhat truculent one. She hadn’t heard anything, and didn’t want to hear anything. It wasn’t as though gentlemen who came to see the Vicar usually got shot. They didn’t. She’d got her own jobs to look after. Colonel Protheroe had arrived at a quarter past six exactly. No, she didn’t look at the clock. She heard the church chime after she had shown him into the study. She didn’t hear any shot. If there had been a shot she’d have heard it. Well, of course, she knew there must have been a shot, since the gentleman was found shot – but there it was. She hadn’t heard it.

The coroner did not press the point. I realized that he and Colonel Melchett were working in agreement.

Mrs Lestrange had been subpoenaed to give evidence, but a medical certificate, signed by Dr Haydock, was produced saying she was too ill to attend.

There was only one other witness, a somewhat doddering old woman. The one who, in Slack’s phrase, ‘did for’ Lawrence Redding.

Mrs Archer was shown the pistol and recognized it as the one she had seen in Mr Redding’s sitting-room ‘over against the bookcase, he kept it, lying about.’ She had last seen it on the day of the murder. Yes – in answer to a further question – she was quite sure it was there at lunch time on Thursday – quarter to one when she left.

I remembered what the Inspector had told me, and I was mildly surprised. However vague she might have been when he questioned her, she was quite positive about it now.

The coroner summed up in a negative manner, but with a good deal of firmness. The verdict was given almost immediately:

Murder by Person or Persons unknown.

As I left the room I was aware of a small army of young men with bright, alert faces and a kind of superficial resemblance to each other. Several of them were already known to me by sight as having haunted the Vicarage the last few days. Seeking to escape, I plunged back into the Blue Boar and was lucky enough to run straight into the archaeologist, Dr Stone. I clutched at him without ceremony.

‘Journalists,’ I said briefly and expressively. ‘If you could deliver me from their clutches?’

‘Why, certainly, Mr Clement. Come upstairs with me.’

He led the way up the narrow staircase and into his sitting-room, where Miss Cram was sitting rattling the keys of a typewriter with a practised touch. She greeted me with a broad smile of welcome and seized the opportunity to stop work.

‘Awful, isn’t it?’ she said. ‘Not knowing who did it, I mean. Not but that I’m disappointed in an inquest. Tame, that’s what I call it. Nothing what you might call spicy from beginning to end.’

‘You were there, then, Miss Cram?’

‘I was there all right. Fancy your not seeing me. Didn’t you see me? I feel a bit hurt about that. Yes, I do. A gentleman, even if he is a clergyman, ought to have eyes in his head.’

‘Were you present also?’ I asked Dr Stone, in an effort to escape from this playful badinage. Young women like Miss Cram always make me feel awkward.

‘No, I’m afraid I feel very little interest in such things. I am a man very wrapped up in his own hobby.’

‘It must be a very interesting hobby,’ I said.

‘You know something of it, perhaps?’

I was obliged to confess that I knew next to nothing.

Dr Stone was not the kind of man whom a confession of ignorance daunts. The result was exactly the same as though I had said that the excavation of barrows was my only relaxation. He surged and eddied into speech. Long barrows, round barrows, stone age, bronze age, paleolithic, neolithic kistvaens and cromlechs, it burst forth in a torrent. I had little to do save nod my head and look intelligent – and that last is perhaps over optimistic. Dr Stone boomed on. He was a little man. His head was round and bald, his face was round and rosy, and he beamed at you through very strong glasses. I have never known a man so enthusiastic on so little encouragement. He went into every argument for and against his own pet theory – which, by the way, I quite failed to grasp!

He detailed at great length his difference of opinion with Colonel Protheroe.

‘An opinionated boor,’ he said with heat. ‘Yes, yes, I know he is dead, and one should speak no ill of the dead. But death does not alter facts. An opinionated boor describes him exactly. Because he had read a few books, he set himself up as an authority – against a man who has made a lifelong study of the subject. My whole life, Mr Clement, has been given up to this work. My whole life –’

He was spluttering with excitement. Gladys Cram brought him back to earth with a terse sentence.

‘You’ll miss your train if you don’t look out,’ she observed.

‘Oh!’ The little man stopped in mid speech and dragged a watch from his pocket. ‘Bless my soul. Quarter to? Impossible.’

‘Once you start talking you never remember the time. What you’d do without me to look after you, I really don’t know.’

‘Quite right, my dear, quite right.’ He patted her affectionately on the shoulder. ‘This is a wonderful girl, Mr Clement. Never forgets anything. I consider myself extremely lucky to have found her.’

‘Oh! Go on, Dr Stone,’ said the lady. ‘You spoil me, you do.’

I could not help feeling that I should be in a material position to add my support to the second school of thought – that which foresees lawful matrimony as the future of Dr Stone and Miss Cram. I imagined that in her own way Miss Cram was rather a clever young woman.

‘You’d better be getting along,’ said Miss Cram.

‘Yes, yes, so I must.’

He vanished into the room next door and returned carrying a suitcase.

‘You are leaving?’ I asked in some surprise.

‘Just running up to town for a couple of days,’ he explained. ‘My old mother to see tomorrow, some business with my lawyers on Monday. On Tuesday I shall return. By the way, I suppose that Colonel Protheroe’s death will make no difference to our arrangements. As regards the barrow, I mean. Mrs Protheroe will have no objection to our continuing the work?’

‘I should not think so.’

As he spoke, I wondered who actually would be in authority at Old Hall. It was just possible that Protheroe might have left it to Lettice. I felt that it would be interesting to know the contents of Protheroe’s will.

‘Causes a lot of trouble in a family, a death does,’ remarked Miss Cram, with a kind of gloomy relish. ‘You wouldn’t believe what a nasty spirit there sometimes is.’

‘Well, I must really be going.’ Dr Stone made ineffectual attempts to control the suitcase, a large rug and an unwieldy umbrella. I came to his rescue. He protested.

‘Don’t trouble – don’t trouble. I can manage perfectly. Doubtless there will be somebody downstairs.’

But down below there was no trace of a boots or anyone else. I suspect that they were being regaled at the expense of the Press. Time was getting on, so we set out together to the station, Dr Stone carrying the suitcase, and I holding the rug and umbrella.

Dr Stone ejaculated remarks in between panting breaths as we hurried along.

‘Really too good of you – didn’t mean – to trouble you…Hope we shan’t miss – the train – Gladys is a good girl – really a wonderful girl – a very sweet nature – not too happy at home, I’m afraid – absolutely – the heart of a child – heart of a child. I do assure you, in spite of – difference in our ages – find a lot in common…’

We saw Lawrence Redding’s cottage just as we turned off to the station. It stands in an isolated position with no other houses near it. I observed two young men of smart appearance standing on the doorstep and a couple more peering in at the windows. It was a busy day for the Press.

‘Nice fellow, young Redding,’ I remarked, to see what my companion would say.

He was so out of breath by this time that he found it difficult to say anything, but he puffed out a word which I did not at first quite catch.

‘Dangerous,’ he gasped, when I asked him to repeat his remark.