По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

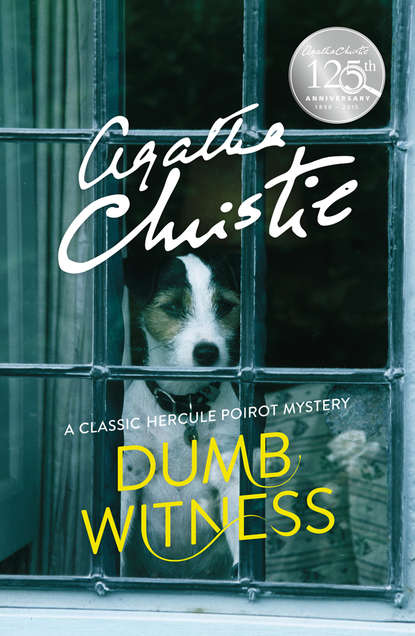

Dumb Witness

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She arrived rather breathless in her employer’s room about five minutes later.

‘I think I’ve got everything,’ she said, putting down wool, work-bag, and a library book. ‘I do hope the book will be all right. She hadn’t got any of the ones on your list but she said she was sure you’d like this one.’

‘That girl’s a fool,’ said Emily Arundell. ‘Her taste in books is the worst I’ve ever come across.’

‘Oh, dear. I’m so sorry—Perhaps I ought—’

‘Nonsense, it’s not your fault.’ Emily Arundell added kindly, ‘I hope you enjoyed yourself this afternoon.’

Miss Lawson’s face lighted up. She looked eager and almost youthful.

‘Oh, yes, thank you very much. So kind of you to spare me. I had the most interesting time. We had the Planchette and really—it wrote the most interesting things. There were several messages… Of course it’s not quite the same thing as the sittings… Julia Tripp has been having a lot of success with the automatic writing. Several messages from Those who have Passed Over. It—it really makes one feel so grateful—that such things should be permitted…’

Miss Arundell said with a slight smile:

‘Better not let the vicar hear you.’

‘Oh, but indeed, dear Miss Arundell, I am convinced—quite convinced—there can be nothing wrong about it. I only wish dear Mr Lonsdale would examine the subject. It seems to me so narrow-minded to condemn a thing that you have not even investigated. Both Julia and Isabel Tripp are such truly spiritual women.’

‘Almost too spiritual to be alive,’ said Miss Arundell.

She did not care much for Julia and Isabel Tripp. She thought their clothes ridiculous, their vegetarian and uncooked fruit meals absurd, and their manner affected. They were women of no traditions, no roots—in fact—no breeding! But she got a certain amount of amusement out of their earnestness and she was at bottom kind-hearted enough not to grudge the pleasure that their friendship obviously gave to poor Minnie.

Poor Minnie! Emily Arundell looked at her companion with mingled affection and contempt. She had had so many of these foolish, middle-aged women to minister to her—all much the same, kind, fussy, subservient and almost entirely mindless.

Really poor Minnie was looking quite excited tonight. Her eyes were shining. She fussed about the room vaguely touching things here and there without the least idea of what she was doing, her eyes all bright and shining.

She stammered out rather nervously:

‘I—I do wish you’d been there… I feel, you know, that you’re not quite a believer yet. But tonight there was a message—for E.A., the initials came quite definitely. It was from a man who had passed over many years ago—a very good-looking military man—Isabel saw him quite distinctly. It must have been dear General Arundell. Such a beautiful message, so full of love and comfort, and how through patience all could be attained.’

‘Those sentiments sound very unlike papa,’ said Miss Arundell.

‘Oh, but our Dear Ones change so—on the other side. Everything is love and understanding. And then the Planchette spelt out something about a key—I think it was the key of the Boule cabinet—could that be it?’

‘The key of the Boule cabinet?’ Emily Arundell’s voice sounded sharp and interested.

‘I think that was it. I thought perhaps it might be important papers—something of the kind. There was a well-authenticated case where a message came to look in a certain piece of furniture and actually a will was discovered there.’

‘There wasn’t a will in the Boule cabinet,’ said Miss Arundell. She added abruptly: ‘Go to bed, Minnie. You’re tired. So am I. We’ll ask the Tripps in for an evening soon.’

‘Oh, that will be nice! Good night, dear. Sure you’ve got everything? I hope you haven’t been tired with so many people here. I must tell Ellen to air the drawing-room very well tomorrow, and shake out the curtains—all this smoking leaves such a smell. I must say I think it’s very good of you to let them all smoke in the drawing-room!’

‘I must make some concessions to modernity,’ said Emily Arundell. ‘Good night, Minnie.’

As the other woman left the room, Emily Arundell wondered if this spiritualistic business was really good for Minnie. Her eyes had been popping out of her head, and she had looked so restless and excited.

Odd about the Boule cabinet, thought Emily Arundell as she got into bed. She smiled grimly as she remembered the scene of long ago. The key that had come to light after papa’s death, and the cascade of empty brandy bottles that had tumbled out when the cabinet had been unlocked! It was little things like that, things that surely neither Minnie Lawson nor Isabel and Julia Tripp could possibly know, which made one wonder whether, after all, there wasn’t something in this spiritualistic business…

She felt wakeful lying on her big four-poster bed. Nowadays she found it increasingly difficult to sleep. But she scorned Dr Grainger’s tentative suggestion of a sleeping draught. Sleeping draughts were for weaklings, for people who couldn’t bear a finger-ache, or a little toothache, or the tedium of a sleepless night.

Often she would get up and wander noiselessly round the house, picking up a book, fingering an ornament, rearranging a vase of flowers, writing a letter or two. In those midnight hours she had a feeling of the equal liveliness of the house through which she wandered. They were not disagreeable, those nocturnal wanderings. It was as though ghosts walked beside her, the ghosts of her sisters, Arabella, Matilda and Agnes, the ghost of her brother Thomas, the dear fellow as he was before That Woman got hold of him! Even the ghost of General Charles Laverton Arundell, that domestic tyrant with the charming manners who shouted and bullied his daughters but who nevertheless was an object of pride to them with his experiences in the Indian Mutiny and his knowledge of the world. What if there were days when he was ‘not quite so well’ as his daughters put it evasively?

Her mind reverting to her niece’s fiancé, Miss Arundell thought, ‘I don’t suppose he’ll ever take to drink! Calls himself a man and drank barley water this evening! Barley water! And I opened papa’s special port.’

Charles had done justice to the port all right. Oh! if only Charles were to be trusted. If only one didn’t know that with him—

Her thoughts broke off… Her mind ranged over the events of the weekend…

Everything seemed vaguely disquieting…

She tried to put worrying thoughts out of her mind.

It was no good.

She raised herself on her elbow and by the light of the night-light that always burned in a little saucer she looked at the time.

One o’clock and she had never felt less like sleep.

She got out of bed and put on her slippers and her warm dressing-gown. She would go downstairs and just check over the weekly books ready for the paying of them the following morning.

Like a shadow she slipped from her room and along the corridor where one small electric bulb was allowed to burn all night.

She came to the head of the stairs, stretched out one hand to the baluster rail and then, unaccountably, she stumbled, tried to recover her balance, failed and went headlong down the stairs.

The sound of her fall, the cry she gave, stirred the sleeping house to wakefulness. Doors opened, lights flashed on.

Miss Lawson popped out of her room at the head of the staircase.

Uttering little cries of distress she pattered down the stairs. One by one the others arrived—Charles, yawning, in a resplendent dressing-gown. Theresa, wrapped in dark silk. Bella in a navy-blue kimono, her hair bristling with combs to ‘set the wave’.

Dazed and confused Emily Arundell lay in a crushed heap. Her shoulder hurt her and her ankle—her whole body was a confused mass of pain. She was conscious of people standing over her, of that fool Minnie Lawson crying and making ineffectual gestures with her hands, of Theresa with a startled look in her dark eyes, of Bella standing with her mouth open looking expectant, of the voice of Charles saying from somewhere—very far away so it seemed—

‘It’s that damned dog’s ball! He must have left it here and she tripped over it. See? Here it is!’

And then she was conscious of authority, putting the others aside, kneeling beside her, touching her with hands that did not fumble but knew.

A feeling of relief swept over her. It would be all right now.

Dr Tanios was saying in firm, reassuring tones:

‘No, it’s all right. No bones broken… Just badly shaken and bruised—and of course she’s had a bad shock. But she’s been very lucky that it’s no worse.’

Then he cleared the others off a little and picked her up quite easily and carried her up to her bedroom, where he had held her wrist for a minute, counting, then nodded his head, sent Minnie (who was still crying and being generally a nuisance) out of the room to fetch brandy and to heat water for a hot bottle.

Confused, shaken, and racked with pain, she felt acutely grateful to Jacob Tanios in that moment. The relief of feeling oneself in capable hands. He gave you just that feeling of assurance—of confidence—that a doctor ought to give.

There was something—something she couldn’t quite get hold of—something vaguely disquieting—but she wouldn’t think of it now. She would drink this and go to sleep as they told her.