По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

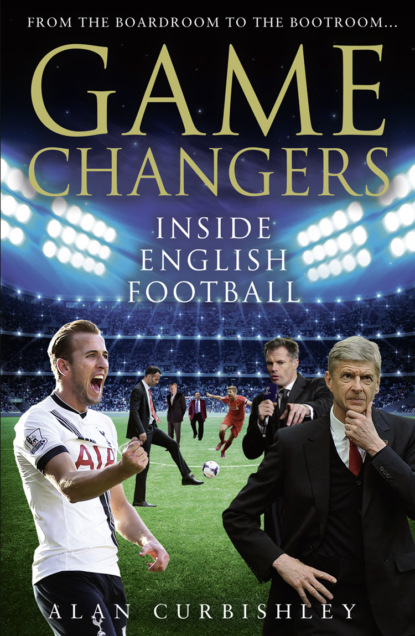

Game Changers: Inside English Football: From the Boardroom to the Bootroom

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u5dbca813-44d2-5c6a-85f0-2694964d15b0)

I can’t remember exactly when I became hooked on football, but I’m sure like many other kids it happened at a very young age. In fact I don’t recall a time when football wasn’t part of my life. It just seems to have always been there.

I’ve been lucky enough to have been able to play the game professionally and continue in the sport as a coach and manager, but before all of that came along I was first and foremost a football fan. I still am. I was born and brought up close to Upton Park, and becoming a West Ham fan was never really in question for me or any of my mates. It was the club we all supported and the one we all hoped to be able to play for one day. I was fortunate to be considered good enough to train with them when I was a youngster, and privileged enough to be given match tickets to their home games. These were little green vouchers that allowed us to stand just behind where the dugouts were later positioned at the stadium. I would always try to make my way to the North Bank behind one of the goals and watch the matches from there. I remember some memorable matches looking on from those terraces, like the day Geoff Hurst scored six goals, including the first one, which he punched into the net, in an 8–0 win against Sunderland in 1968. I also watched on in despair as a great Manchester United side inflicted a 6–1 defeat on the Hammers in 1967, the season the visitors went on to win the league. So later on in my life being able to actually play for the club and manage – it was something special.

Having the good fortune to be professionally involved in the game for most of my life has given me an insight into the workings of football in this country, and during that time I have seen the game grow, change and evolve from those matches I watched as a youngster in the 1960s to the industry it now is. I wanted to go behind the headlines and the general media coverage to try to shed some light on exactly what happens in the game. To interview the sort of people who are part of the fabric of the modern game in this country, and who play, or have played, important roles in what football is now about.

There are some very familiar names included, but equally there are others who are not so well known, and perhaps some who are not known at all outside of the game. However, they all share something in common, and that’s football. There are many people involved in the game and who earn their living from it. They are part of what modern football is about, and although it would have been impossible to include everyone who plays a part, I have tried to speak to people who I believe can shed some light on the workings of the game at the top in this country.

Supporters see their favourite team or player running out onto the field each week, but might not have any idea about those involved in making sure that can happen – people such as the coaches, the medical and sports science team, the player liaison officers and the kit men. They all play their part, and that is why I have tried to talk to a broad cross-section of people from the boardroom to the bootroom.

Things are always changing in football, with managers, players and others involved in the game moving on or changing clubs. The vast majority of the interviews I conducted took place in 2015, with the others happening in the early part of 2016. Although circumstances may have changed for some of the people I spoke to at the time, I hope the relevance of what they told me and the candid way in which they were prepared to speak about their roles within the game give the sort of insight that fans will be interested in.

Football at the highest level might now be an industry, but at the same time it is still a very simple game with very simple rules. The drama, spectacle, excitement, happiness and sadness that come along with it make it special for those of us who love it. Once you’re hooked, football becomes an addiction – and it stays with you for life.

Chapter 1

Manager (#u5dbca813-44d2-5c6a-85f0-2694964d15b0)

Sir Alex Ferguson, Arsène Wenger, Harry Redknapp, Chris Powell

When it comes to talking about football management in Britain there is probably only one place to start. If you’ve won two Champions League finals, a couple of European Cup Winners’ Cups, seventeen domestic league titles and fourteen domestic cup competitions, the chances are you know what you’ve been doing. Add to all of that a managerial career that lasted for almost forty years, twenty-seven of which were spent at Manchester United – one of the biggest clubs in the world – and you can see why Sir Alex Ferguson has rightly earned legendary status as one of the greatest managers of all time.

He took his first steps in management in 1974 with East Stirlingshire in Scotland, and then went on to have success with St Mirren, winning the Scottish First Division, before taking over at Aberdeen for eight years, during which time he won three Scottish Premier Division titles, four Scottish Cups, one League Cup and, perhaps most remarkably of all, the European Cup Winners’ Cup. During his spell at United he not only won the Champions League twice, he also guided his teams to an incredible thirteen Premier League titles in the space of twenty years. He built and rebuilt his United teams, producing an attacking brand of football that enabled the club to become consistent winners.

Throughout his time as a manager his fierce drive and determination to win stayed at the centre of what he was about, producing teams on either side of the border that were successful and entertaining. As a manager I faced Alex’s teams on several occasions, and the one thing you could always be sure of was that they were going to come after you and attack, whether it was at Old Trafford or your own ground. His teams played in a certain way and were incredibly successful as a result.

‘It was the way I was,’ he says. ‘At Aberdeen I always played with two wide players and at St Mirren I always played with two wide players, and I always had a player who’d play off the centre-forward. When I started as a player I had a wee bit of pace, but when I got towards the end of my career I used to drop in and it’s a problem for defenders. Brian McClair was the first one to do it for me at United, when I had Mark Hughes with him. Then it was Hughes and Cantona, then it was Andy Cole and Cantona. I’ve always done it.’

Something else he always did as a manager was to go for a win where others might have settled for a draw. I remember some years ago Alex telling me he didn’t do draws, and he’d often end up with five forwards on the pitch because he always wanted those three points.

‘Yes, that’s why I was prepared to take a risk in the last fifteen minutes of a game,’ he admits. ‘We just threw them all up front! Sometimes it was dictated by substitutions our opponents made. A lot of them would put a defender on, that gave me the licence to bring an extra forward on. Reducing their own attacking position meant I could risk it. I think risk is part of football. I never worried about it. I was always happy to have a gamble.’

Those gambles paid off on so many occasions for United, and they were something that ran right through his time at the club. Players came and players went, teams were built and then rebuilt, but the level of success never dropped as United consistently won trophies. Yet it wasn’t all about success for Alex during his early years at the club, and after three years with them he hit what was to be one of his worst periods in management.

‘I had a really bad period at United in 1989,’ he recalls. ‘In the whole of December I never won a game. We had a lot of injuries. But no matter who you are your job is to win games, and it was probably a lesson for me in how to handle that part of the game. At United you’re expected to win. That’s the expectation – and it was a great lesson for me. I used to pick teams with five players injured, and the games in December come one on top of the other during that Christmas and New Year period.

‘I remember we played Crystal Palace at home and lost 2–1, and we were 1–0 up. It was one of those horrible rainy days in Manchester, and when I got home I got a call to say we’d drawn Nottingham Forest away in the FA Cup, who at that time were arguably the best cup team in the country. When we got to that game we still had a lot of players injured. You’d find it impossible to think that the team won that day, but they did. We had players playing out of position, we had Ince out, Danny Wallace out, Neil Webb was out – and we won. We won 1–0 when Mark Robins scored. One of the best crossers I had at United, of all time, was not a winger. It was Mark Hughes. He was a fantastic crosser of a ball, with either foot. He got the ball on the wing and then bent it in with the outside of his foot. In actual fact, Stuart Pearce shoved Mark Robins on to the ball and he scored. We won, went through and won the cup that season.’

The FA Cup win in 1990 after a replay against Crystal Palace at Wembley was the first trophy Alex won as United manager, and it was followed the next season by victory in the European Cup Winners’ Cup. In 1993 United became the first winners of the newly formed Premier League. That year not only ushered in a golden period for United in terms of their title-winning ability as a club. It was also the dawn of a new era in English football, with television money playing a significantly more prominent role for those clubs who were part of the Premier League. It was one of the major changes to take place during the time he was in charge, although there have been others that he feels have had an impact on managers.

‘I came into management before Sky really took off. I started in 1974 when I was thirty-two years of age, so when those various changes happened and the explosion came I had the experience to handle all of that,’ he says. ‘You integrated into all the various changes, so in terms of dealing with players at that time I could see if there was a change in the player’s personality because of the success we were having. I could deal with that because I had a few years behind me. I always remember when I started at Aberdeen the vice-chairman, Chris Anderson, said to me, “We need to be at the top of the Scottish Premier Division when satellite television comes in.” I had absolutely no idea what he meant, but I didn’t want to say, “What do you mean?” It just registered in my head that I had to be successful. The way Sky have elevated the game and made all these players film stars, in terms of the way they are recognised now – that changed everything. But the one place you wanted to be was the Premier League.

‘The other thing which changed was ownership of clubs. You wonder why these owners – from America, from China, from the Middle East – why are they there? Is it because of television? I think it must be part of the reason. Can you imagine if Premier League teams were allowed to sell their own television rights? It’s never happened, but you say to yourself, “Well, it may change.” If Manchester United were to sell their television rights they’d be comfortably the biggest club in the world.

‘The other change of course was the Bosman rule. It was a massive change and it caught us all on the hop. Nobody expected it. All of a sudden you were panicking, and that created the explosion of agents – there’s no doubt about that. You had guys who were agents in the music industry who wanted to be football agents, and that was a seismic change for managers, having to deal with all that. So the manager had the training through the week, he’s got to pick the team on the Saturday, he’s got a board meeting to answer to directors and he’s got his television interviews. But on top of that you’ve got agents plugging away. They’re maybe phoning other clubs – “My player’s not happy” – we know it happens, not everyone, but some of them do, and they negotiate with you knowing they’ve got a full deck of cards under the table. “Well, we’ll think about it.” I don’t know how many times I’ve heard that – “We’ll think about your offer.”

‘If you were to write down the things a manager has to deal with, managers wouldn’t want to be managing! They have a massive task – the managers of today – massive, and the media is a big problem. They are under pressure. They need to be successful – just like managers – and get a piece in the papers, but they’re up against things like the internet and Sky television. They used to run my press conference on a Friday, or bits of it, through the whole day. That used to get me really annoyed.’

Alex has always had a great affinity with other managers, and was invariably there to wish a young manager luck when they got their first job. He knows just what a tough profession it is for everyone, whether they achieve the level of success he has had with a top club like Manchester United or simply toil away in the lower leagues. They are at either end of the managerial spectrum, and then there are all the other managers in between who do a great job week in and week out but perhaps never hit the headlines. Only a handful of managers can win trophies or get their side promoted each season, but so many others have done fantastically well throughout their careers, and it’s clear he not only values them as friends but also knows just what good work they’ve done.

‘When I was at Aberdeen the most regular calls I used to get about players in Scotland were from Lennie Lawrence, who was at Charlton, and John Rudge, who was at Port Vale. Rudgie must have been on the lowest budget in the history of the game! But he used to live with that. He would find a way of getting players on loan, and only if you’ve been in the job do you realise how difficult that is. Lennie Lawrence would be on the phone asking about players, and when I first came down to England, if you went to a reserve game these same guys were at the matches.

‘They were a great example of perseverance and staying in the game – surviving. They were good guys and I enjoyed working with them. David Pleat was another one who phoned a lot, and Mel Machin, who was at Norwich. When I came down to England I relied on one person for my information on other teams – John Lyall at West Ham. John Lyall and I met on holiday once and we got very friendly. When I came down here he was fantastic for me. He sent me all his reports on the players, the games, the teams. For the nine months until I got my feet under the table, got my scouting staff sorted out, he was very good to me.

‘There were quite a few managers I knew reasonably well, like Keith Burkinshaw, and another manager who needs recognition is Dario Gradi, who was at Crewe – and he’s still there. You look at these managers, the Lawrences and the Rudges, they’re still in the game. So they were there before I came and they were there after I’ve left! Realistically, you should have a reasonable amount of success with a club like Manchester United. With the resources, the history – you should have reasonable success. These guys have a place in the game. They’ve not won the FA Cup, or the Premier League or European cups, and they’ve had harder jobs than I’ve had. If you look at Lennie Lawrence and John Rudge, their success has been relative to their resources. As a manager it’s up to you to make the best of what you’ve got.’

You don’t stay in any job for as long as Alex did without being able to adapt and change as the game around you changes. I think his ability to do this, and at the same time retain the kind of football beliefs and attitude he always had, was a key factor for him. He embraced change and innovation but at the same time trusted his own ability and experience as a manager, maintaining a level of authority at United that saw him stamp his own personality on pretty much everything at the club. Sir Alex Ferguson was Manchester United, while the traditions and history of the club very quickly became a part of Sir Alex, something that stayed with him throughout his time at Old Trafford.

‘Accepting change is really important,’ he says. ‘You should look at change. The way I addressed it was if someone gave me a paper that convinced me it was going to make us 1 per cent better, I’ll do it, particularly the sports science. With video analysis I trusted my own eyes. I looked at it and used it for the players. We needed to in the sense that we’d break it down into what I said, and that’s all you need to give them, because it was about us. When the video analysts showed me things, I knew all that because I’d seen all these players before. I’d been in management a long time, I trusted what I knew about my players and my opponents.

‘My team talk when it came to opponents was, “Who’s their best player, who wanted the ball all the time? Pay attention to that one,” in terms of reducing the space or time he had on the ball. I never bothered about any of the rest of it. I talked about certain weaknesses. But it was all about our own team. I know more about my own team than I know about any other team. I think a lot of people rely on video analysis too much. It’s important, the details are important, and if it helps you 1 per cent, do it. But I never made it my bible.’

Many people wondered what life would be like for Alex after he decided to retire, but he’s as busy as ever with various engagements that fill up his diary months in advance. It strikes me that the work ethic that has always been such a feature of his life will never leave him. No matter what he does, that drive and enthusiasm come shining through. But there are some things that he misses about not being a manager, including the family feel he loved at the club.

‘The buzz of the big games,’ he admits. ‘And you miss people, like the staff you had there, and the players and training. You miss that part, and I had a great staff – not just my own playing staff, but the people, the groundsman, the girls in the laundry, the girls in the canteen. When I went to United the stewards were all in their sixties – they were all older guys. They were hand-me-downs, from grandfather to father to son, and they were never paid. The way they were repaid was that if we got to the final they were all invited to the game for the weekend. If we didn’t get to the final they used to have a big dinner at Old Trafford. Me and the staff all went. There’d be maybe 1,000 people there, and in a way they were the institution. They had a bigger tie to Manchester United than anyone, because they went back to their fathers and grandfathers. But then the law changed in terms of security and insurance, and they had to stop it. Today the stewards are all paid.

‘My best period at United was every time I won the league, the first one and the last one, the European cups – these are the moments we’re in it for. That’s what I miss today, the big finals. You can’t beat that, or the game where you win the league and you’re waiting to see the results of other teams. The tingle you get from that.’

For a large part of Alex’s time Arsène Wenger and the various teams he produced as Arsenal manager proved to be among United’s main rivals. Arsène took over at Arsenal twenty years ago, and his management has not only seen the north London club win Premier League titles and FA Cups, as well as consistently playing in the Champions League year after year. He has also been a major factor in building the club both on and off the field.

During his time he has produced great sides, including the ‘Invincibles’ of 2003–04, who went the whole season unbeaten as they won the Premier League title. He also oversaw the construction of a new training ground at the end of the 1990s and the club’s move from Highbury to the Emirates Stadium ten years ago. When Arsène arrived in England the Premier League landscape was very different. Apart from Ossie Ardiles and Ruud Gullit, we didn’t really have foreign managers in charge of our top clubs, and when he showed up at Highbury not too many people had heard of him.

‘There was a lot of scepticism about foreign managers when I arrived,’ he admits, ‘because you had no history of successful managers from abroad and there was a kind of belief that foreign managers couldn’t adapt here. There was a double scepticism about me because nobody knew who I was, and it was, “Arsène who?” I could see as well from the way the players looked at me that they were thinking, “What does this guy want?” One of the problems is that you always have to convince the players, but to start well you also need luck. And my luck was that I inherited a good team, players who were all basically over thirty, very experienced and very intelligent.

‘I had Seaman, Dixon, Adams and Winterburn – they were all over thirty and they were winners – and I had players like Platt, Merson, Ian Wright and Dennis Bergkamp. It was a team. They were all experienced. The other good thing was that they had not made money. When I arrived it coincided with the TV money that was coming into the league. Ian Wright was a star and he was earning £250,000 a year, and from the time I arrived until a year or two later it went from £250,000 to £1 million. So when you are over thirty and suddenly you go from £250,000 to £1 million or £1.2 million a year, if you can gain one more year you’re hungry. In fact, in British football we’ve gone from people who made their money after thirty to today, where they make their money before twenty! And that’s a massive problem.

‘So when I arrived I was able to convince the players that if they were serious, if they were dedicated, if they did my stretching and my preparation they would have a longer spell as a player. And I always gave them one more year, so the carrot was always there. They knew they had to fight for one more year. They were ready to die on the football pitch and that was my luck. They had the quality and they were hungry, and of course that helped. I believe when you come here from a foreign country you have to adapt to the local culture. You bring your own ideas, but you must not forget that you have to adapt to the culture.’

Part of the culture that confronted Arsène was something very different to what he had been used to. Back then it was still quite normal for players to enjoy themselves and go out for a drink after matches. They played hard and put the work in on the pitch, but then enjoyed themselves off it. It was still often a case of a team eating fish and chips on the coach when they were travelling back from an away game.

‘I changed that, but the fact that we were winning and the players were getting bigger contracts helped,’ he says. ‘When you multiply your wages by four as a football player, that’s not common, but they were intelligent and they were men. I did feel sometimes, “Are they going to be able to play on a Saturday?” I came from France where in training you worked hard, but on Saturday sometimes the players disappointed me. But I discovered here a generation that when the game started on a Saturday, they were competitors. I think you can play to play, you can play to compete – and you can play to win. These guys played to win. On Saturday they were ready absolutely 100 per cent to play to win.

‘I slowly changed the diet, the training, and put across my ideas. I adapted a little bit as well, I changed things slowly and I encouraged my players at the back to play more. I came here with the idea that they could not play football, and that’s when I discovered they were much better technically. It was a pleasant surprise because I encouraged them to play – and they liked it, they were capable of doing it. Bould, Adams, Winterburn – they were players, and I think we all met at the right time.

‘I came here because of David Dein – he believed in me. I was lucky enough to meet somebody who gave me the chance to come to England and I will be grateful forever for that. He came a few times to Monaco when I was manager and we had a good relationship. Before I went from Monaco to manage in Japan I met with him and Peter Hill-Wood, but in the end they decided to go for Bruce Rioch as Arsenal manager. I went to Japan for a year and in the second year they came to see me and said, “We want you to take Arsenal.” The most important thing in this job is to have good players. That’s the only thing that matters, basically. No one can make miracles. I was lucky that when I came here I had a top team.

‘What I like in England is the respect for tradition, but they are also crazy enough to innovate. It was surprising, but that’s what I think I admire about this club – they have respect for the traditional values of the game and they keep them alive. But they took a French guy, who at that moment nobody knew, and there was no history of successful foreign managers in England. When I arrived it was nearly impossible to get a chance if you were foreign. I would say that today it’s the reverse. It’s much more difficult for an English manager to get a job in the Premier League than for a foreign manager. It was down to David Dein believing in me and giving me that chance.’

I can remember reading that Arsène had signed Patrick Vieira and then Emmanuel Petit on five-year contracts, and at the time it was quite unusual for a British club to be signing players from France or any other country, really, because we were pretty insular when it came to our football. With a few exceptions managers tended only to sign British players, so it all seemed very different, and not a lot of people knew that much about either of them.

‘At that time, on the French market, I was alone,’ he says. ‘I could go and pick a good player and they were ready to come over to England with me. I knew Vieira from the French league and I had Petit as a player when he was at Monaco. I thought at the time that they both had the physical stature – as well as the ability – to play in the Premier League. I remember when we went out in the tunnel before matches you had Bould, Adams, Petit, Vieira, Bergkamp, Ian Wright. They were massive, the guys were absolutely massive, and you won half the game before you went out. So at that time I could take from the French market what I wanted, and there were good players in France. Today, if you go to the French league there are forty-three scouts and twenty-five are English – so it’s much different now.’

I was at Charlton as a manager for fifteen years, Alex and Arsène have even more years at one club, and I honestly can’t see that happening again. Managing at any level, particularly in the Premier League and the Championship, is much more short-term now for a manager. If Arsène was walking into Arsenal today he probably couldn’t afford to think beyond three or four years. That’s the reality for a manager these days, and it’s one of the big changes to have taken place during his time in England.

‘Firstly, what has changed is ownership,’ he says. ‘When I arrived it was all local. The owners had bought “their” football club. They were fans as kids, were successful in life and then bought the club they loved. It’s different today, it’s an investment – and people are scared to lose their investment. We as managers are under pressure to be successful. It’s a billionaires’ club today.