По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

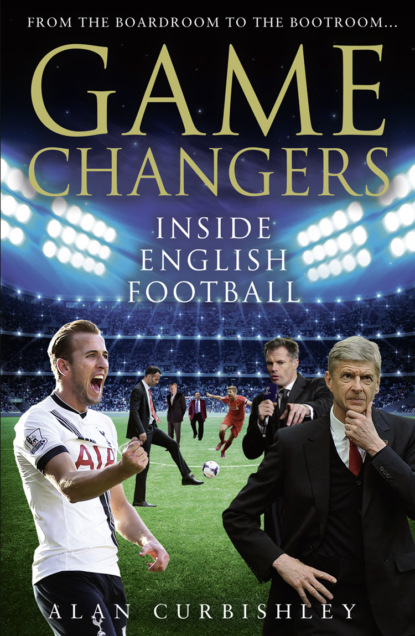

Game Changers: Inside English Football: From the Boardroom to the Bootroom

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What you did at Charlton, and what I have done, is carry the values of the club through the generations, and you have that as a reference when a player comes in. I can say to the player, “This is the way we do things. We do this, we don’t do that, you have to behave like this and not like that,” because I’ve been here for a long time. If the manager changes every two years he’s in a weak position to say things like that. The manager is not the carrier of the values of the club any more. I think it’s very important that the values of the club are pushed through by the manager.

‘I believe a manager has an influence on three levels. The first is on the results and the style of play. The second is the individual influence you can have on a player’s career. Players can have a good career because the manager has put them in the right place, given them the right support, the right training. So you can influence people’s life or career in a positive way, and the third is the influence you have on the structure of the club. I was lucky because when I arrived we had no training ground; we had Highbury, which is the love of my life, but it only had a 38,000 capacity. We got the training ground and the new stadium, and I was part of that, so that gives you a kind of strength as well. We had to pay back the debt. We knew we had limited money and we had to at least be in the Champions League to have a chance to pay off the debt.

‘That was the most difficult period for me. For a while it was very bad, but today the club are financially safe. I personally believe the only way to be a manager is to spend the club’s money as if it were your own, because if you don’t do that you’re susceptible to too many mistakes. You make big decisions and I believe you have to act like it’s your own money. Like you’re the owner of the club and you can identify completely with the club, because if you don’t do that I think you cannot go far.’

To be at a club for as long as Arsène you of course have to cope with changes in the game and with things like the age difference that inevitably opens up when you’re a sixty-six-year-old manager dealing with young players, some of whom are teenagers. He has needed to keep himself fresh, enthusiastic and motivated, as well as retaining the authority that any manager needs. So how has he gone about it?

‘It’s linked to the fact that you want to win the next game and you want to do well,’ he insists. ‘I believe you cannot stand still, you have to move forward. Look at Alex Ferguson – he was not scared to innovate, he did not stand still. I believe that if you want to stay a long time in this job you have to adapt to evolution. Today I’m more a head of a team of assistants. I manage the players, but I manage my own team as well. You have a big medical team, you have a big video team, you have a big scouting team, you have inside fitness coaches, outside fitness coaches. You know, when I first started and coached I was alone with the team and I was thirty-three years old. I was alone with them – and that’s what I liked, that’s what I’ve always liked. I like to go out every day. I don’t like the office. I don’t like paperwork too much. I like football to be more outside than inside.

‘When it comes to the age gap with players, I try to speak about what matters to them. I cannot give them the last song of the latest rapper in the country, but what I can tell them is how they can be successful. That matters to them. With the difference in age I cannot act like I’m twenty, but what hasn’t changed is that the boys try to find a way to be successful, and if I can connect with them in that way I have a chance. I have people who are more in touch with them, who give me the problems they have and then I can intervene at the right moment. But also if you are a young boy sometimes an older guy can give you reassurance on what matters to you. I try to do that – I say I can help them because I’ve done it before, and so they trust me. I believe what is for sure is that if you stay for a long time at a club, people have to believe that you’re honest. That gets you through the generation gap, that’s what I think is most important, because players don’t expect you to be young when you’re sixty-six. But they expect that when you say something, it’s true. If they believe you are honest you have a chance.

‘With authority, I think that some people have that naturally, and secondly as managers, we have the ultimate power – to play them or not to play them! On top of that, the player knows that if he wants to extend his contract he has to go through me. He cannot go to the chairman. That is massive. The player knows there’s one boss and as long as you have that in a club, you have the strength.

‘The more people you have inside the football club the more opinions you have. You have to have a good team spirit in the club, but everyone should just do their job. Do your job, and no more. Do not do the job of your manager. And sometimes when people stay a long time at the club, they have that tendency to have an opinion on everything. Do your job, don’t intervene in what is not your responsibility and respect everybody else in his job. So we have to find a compromise between a family feeling and a respect that you don’t do what is not your responsibility.’

So in those twenty years at Arsenal what have been the biggest changes for him?

‘When I started the eye of the manager was the only data that was important, but today the manager is inundated with different types of information,’ he says. ‘He has to choose the four or five bits of information that are valid, that can help him to be successful. I believe the trend will be that the technical quality of the manager will go down and down, because he will be surrounded by so many analysts who tell him basically, “That’s the conclusion the computer came to, that’s the team you should play next Saturday.” So we might go from a real football person to more a kind of head of a technical team.

‘The power of the agent is another thing that has changed in the last twenty years. I’ve fought all my life for footballers to make money, but when you pay them before they produce it can kill the hunger. I’m scared that we now have players under seventeen, under eighteen, who make £1 million a year. When Ian Wright was earning that he’d scored goals, he’d put his body on the line. Now before they start they are millionaires – a young player who has not even played!

‘What I do think will happen is that you will have more and more players coming out of the lower leagues who have had to fight their way through. Compare that with a player who has been educated here, who has had Champions League for seventeen years, who has not known anything else. So it’s not a dream, it’s normal for him, but if you play for a team in the lower leagues and watch Real Madrid or Barcelona on Wednesday nights you think, “I’d love to play in games like that.” I’ve said to our scouts to do the lower leagues because the good players are there now. Don’t forget we have many foreign players in the Premier League, but good English players have to go down to develop.’

Arsène’s own hunger for the game and for management is very obvious when he talks about football. Like any manager he loves winning and absolutely hates to lose. The thought of retirement seemed a long way off when we talked, even though he knows it’s inevitable one day.

‘It’s been my life, and honestly, I’m quite scared of the day,’ he admits. ‘Because the longer I wait, the more difficult it will be and the more difficult it will be to lose the addiction. After Alex retired and we played them over there he sent a message to me to come up and have a drink with him. I asked, “Do you miss it?” He said, “Not at all.” I didn’t understand that. It’s an emptiness in your life, especially when you’ve lived your whole life waiting for the next game and trying to win it. Our pleasure comes from that – and our suicidal attitude as well!

‘As people, part of us loves to win and part of us hates to lose. The percentage to hate to lose in me is bigger. Managers hate to lose, and if you don’t hate to lose you don’t stay for long in this job. If a match goes really well I might go out with friends or family for dinner or a drink. If it doesn’t I’ll go straight home to watch another football game and see another manager suffer. If we lose it ruins my weekend, but I’ve learned over the years to deal with my disappointments and come back. What helps is when you come in, speak to your assistants, and then sometimes do a training session and start afresh. You could stay at home for three days without going out if you wanted to, but at some stage life must go on.

‘The next game gives you hope again.’

All managers will be able to empathise with Arsène when he talks about losing. The despair of defeat for a manager is far greater than the joy of winning a match. When you win it’s a relief and a time to briefly enjoy the victory that night, but even by the time you get in your car for the drive home your thoughts start to stray to the next match and what you have to try to do in order to win it. When you lose, that horrible feeling stays with you for a long time and it’s hard to shake off. You’ll replay the game over and over in your mind, thinking about what went wrong and what could have gone right. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been in the game, what you’ve won and achieved or how much experience you have. All managers experience very similar emotions.

The most experienced English manager in terms of the Premier League is Harry Redknapp, with more than 630 matches under his belt. Harry first became a manager in 1983 at Bournemouth, and in more than thirty years in the job has been in charge at West Ham, Portsmouth, Southampton, Tottenham and Queens Park Rangers. He’s one of the best-known managers in the country, with bags of experience. He’s always had an eye for a player and has always tried to fill his sides with footballers who have flair and are not afraid to express themselves on the pitch. He also rightly earned a reputation as one of the game’s best man-managers and during his career was ready to take a gamble on some players who other clubs had given up on as they’d proved to be too much of a handful.

‘The first thing I always look for in a player is that ability,’ he insists. ‘And then you think, “Yeah, I can get the best out of him.” Those mavericks, if you can get them playing then you know you’ve got a fantastic player on your hands, and I enjoyed doing that. Di Canio at West Ham, Paul Merson at Portsmouth, Adebayor at Tottenham, young Ravel Morrison at Queens Park Rangers. You think if you can get them on side they can play, because they’re fantastic footballers. I always look for talent first and foremost, because I love people who can play. I would still take Adebayor again, I would still take Ravel Morrison because there’s something about him. I loved his ability, and if I took a club now and could get him in I’d take him tomorrow. Talk about ability – I didn’t know how good he was until I got him at QPR.

‘I always think there’s good in people, and I get on well with people. I look at them and think, “Come on, you’re wasting your talent.” I think that challenge of trying to get the best out of them is something I enjoy doing. I’ve always done it. Even at Bournemouth I had lads who could be a bit of a handful and at times it was hard work, but they did great for me when it came to playing and I loved that. You certainly have to handle players differently these days; managers can’t shout and scream at players like some did years ago. Players don’t respond to it and they can’t accept it.’

Harry’s ability to coax the best out of players and to put together entertaining teams has always been a trademark of his. His early days in management at Bournemouth in 1983 may have been very different to his time at QPR in more recent years, but he always applied certain principles to the way his teams played.

‘When I started you went out and signed the lads on, there was no money and it was a struggle. Even something as basic as pre-season training was difficult. When I was at Bournemouth we never had a training ground. You’d go in the park and train. For one pre-season we found a field in the middle of nowhere that belonged to a little cricket club and they let us use it to train on. But we didn’t have any facilities for food, so I used to go to a local supermarket in the morning to get some French sticks and my missus would make ham and cheese rolls for the players. When I was there it was you, maybe a coach, the physio and the kit man when you played away games, four of you, and everything was put into two baskets – shirts, shorts, the lot. Now when a team in the Premier League play an away game it’s like you’re going away for a year, with trucks full up with gear. I didn’t know who all the people were when I was at Tottenham. There were people there on a Saturday and I didn’t even know what they were doing there! We had so many masseurs, physios, analysts – so many people.

‘I think it’s completely changed for managers now. In the old days you’d do everything. You’d go and watch players, sign them, train them. You ran everything. That doesn’t happen now. Agents don’t deal with managers, they deal with chairmen and chief executives. They know managers are only passing through. I found at Tottenham that a player would very rarely come and see me about football. When a player had a problem they would talk to their agent, who would ring up the chairman and complain about me not picking them or something. The agent would be straight on the blower to Daniel Levy.

‘I think the way managers have to operate now is very different. Like most managers, I used to go out and watch a lot of games looking at players. You’d go to a game and there’d be five or six other managers sitting in the directors’ box as well, because we were getting all of our players from this country. Now they don’t go to watch players. How can you when clubs are signing them from places like Argentina or Uruguay? Scouting systems are different now. You used to have a chief scout – he was the one who would bring players to you. Now so much of it is done by videos or whatever, because that is the way you get to look at players. If you get to go and see a player now it’s a miracle.

‘I think there was also a lot more contact between managers in the past than there is today. You would phone them and speak to each other more, and there was a camaraderie. When I was at West Ham we needed a striker. I remember going to watch a game in Scotland because I wanted to have a look at a particular player. When I got there the manager of this player saw me and actually warned me. He told me not to touch the player with a bargepole because he was a nightmare! There aren’t many people who would do that nowadays, and it’s very different for young managers.

‘When I started I had some sort of grounding. It was a great experience, because you basically learned the ropes. Now, if you’ve played in the Premier League, to go and take a job in the lower leagues is very difficult, because you don’t know the league and you don’t know the players. I went to Oxford City with Bobby Moore years ago before I became a manager, and we never had a clue about any of the players at that level. It was different at Bournemouth for me. I’d played for them, I knew the level and when I got the job as manager I knew that division.’

So will players from the Premier League who want to go into management be prepared to learn their trade and cut their teeth at a lower level as Harry did before getting a crack at the top division, rather than expecting to get a job with a big club straight away?

‘The problem is if a player has been earning £150,000 a week in the Premier League, is he going to take a job in one of the lower leagues for a grand a week?’ asks Harry. ‘He’s earned more money in a week than he will in a year as a manager down there, and he’s going to be thinking, “Now I’ve got to work all year for what I was earning in a week. And instead of getting home at two in the afternoon and having the day to myself, I’ve got to be out grafting!” It’s difficult.’

Like all managers, Harry’s had his ups and downs in the game. He did brilliantly at Portsmouth, getting the club promoted to the Premier League and then keeping them up against the odds, as well as leading them to victory in the FA Cup Final in 2008 against Cardiff. Another major highlight for Harry was leading Tottenham to a Champions League place in 2010 and taking them to the quarter-finals of the competition. The team he had then at Spurs, with the likes of Bale, Modric and Van der Vaart, was a really exciting one, and perhaps with another player or two they could have gone close to actually winning the title during the time Harry was manager at White Hart Lane.

‘It was a great time for me and going into training was a pleasure,’ he recalls. ‘They’d be zipping the ball about, Bale, Modric, Van der Vaart, world-class players. It was a team. They’d have been up in the top four every year that group, but then they sold Modric and then after I left they sold Bale, but that was a good team. When I went in there in 2008 we changed some things around, pushed Bale forward and shoved Modric from wide left and put him in the middle of the park and his career took off then. Bale hadn’t played on a winning Tottenham team for ages, but you always knew he was a fantastic talent.’

Harry lost his job at Spurs in 2012 but then went on to manage QPR, guiding them back to the Premier League after relegation, before deciding to resign in 2015. He’s very much a football man who still loves the game, despite all the changes there have been, and through it all Harry’s eye for a player and his natural ability to get them on side have never changed.

‘I think players respond more to a pat on the back than someone shouting and screaming at them,’ he adds. ‘Bobby Moore once said to me that our manager at West Ham when we were players, Ron Greenwood, had never once said “Well done” to him. Bobby said we all need that in life, someone coming up to you and saying, “You were great today.” People respond to things like that. Players do as well, and I think that’s important.’

While Harry is a vastly experienced manager, Chris Powell is at the other end of the scale. Chris played for me at Charlton and did a fantastic job. It didn’t surprise me when he eventually went on to coach and then turned his hand to management. Ironically, his first full-time managerial appointment was at Charlton, where within the space of little more than three years he experienced both the success of getting the club promoted and the disappointment of losing his job when a new owner took over. Six months later he was back as a manager with Huddersfield, but his time there lasted just fourteen months before he lost his job. It’s been a pretty steep learning curve for Chris, but despite the disappointment of losing his job twice, and knowing the pressures and stresses that go with the career, at the age of forty-six managing is still something he’s determined to carry on doing.

‘I think managers do the job because they love the game,’ he insists. ‘We all love the game. That’s why I do it and it’s why I want to continue doing it. When you go into it you have to be prepared for all the positives and all the negatives that the job will bring. We all have an expectation of how things will go when we take over a club, and you hope that things will go well. But you have to be prepared for the setbacks, and at the same time you have to have a go and put yourself out there. As a manager you’re ultimately on your own – you make the calls and decisions, that’s the manager’s lot. Not everyone is going to be happy with the decisions you make, whether it’s the players, supporters, the media, but you still have to have that inner belief that what you’re doing is right.

‘I think I always had it in my mind that I wanted to be a manager. I got the opportunity to coach when I was at Leicester, and that was invaluable because it was a great education to be involved every day and to see how the manager and coaches prepared, but there’s not a thing in the world that can prepare you for being the number one. When you’re a coach you think, “I can do that, I can be a manager.” But it’s when you actually become a manager and walk into the office on your first day with everyone there and looking at you, that’s when you realise they’re all thinking, “Right, what are you going to do?”

‘When I was at Leicester I got a call to go for an interview at Charlton for the manager’s job. Within twenty-four hours I was their manager, which felt great, but that’s when everything else starts to kick in and you begin to appreciate how much the job involves. There’s so much that you have to organise, and you soon realise that no matter what department in the club, it all comes to you. I think that was the biggest change for me. When I went to Charlton as manager they were in League One. As a coach you organise and do everything you need to for the day, and then you go home. As the manager that doesn’t happen. You speak to the owner, you speak to the chief executive, you speak to the head of recruitment, you speak to agents – it never seems to stop. What you do have to do is try to organise some sort of time for yourself, but that in itself is hard to do because you want to do the job right, you want to do it well and you have to get involved in everything.

‘One of the big things that hit me when I first got the job was when I walked out at the Valley for my first game there. I walked to the technical area, the whistle blew and I thought, “I’m leading this team now!” I’ll never forget it. I turned round and looked at the dugout and the main stand during the game and thought, “This is it. You always said you wanted to manage. Now this is it.” You stand there and you’re really on your own.

‘Winning as a manager surpasses winning as a player because it’s the culmination of your work through the week, and to see it come together on a Saturday with a win, especially if the performance is to the levels you expect, it just surpasses everything. But if you lose it’s terrible. There’s no middle ground. It’s so up and down, but as a manager you know that’s in front of you when you take the job. You don’t switch off, you’re forever thinking about it. Managers are quite good actors – they’ll say they’re going out for a meal with their family to relax and enjoy themselves after a match, but all through that meal they’re just thinking about the game they’ve just played and the next one that’s coming up.

‘I think the first six months I had at Charlton were invaluable. I had time to think about the next season and the restructuring I wanted to do with the team to try to get us promotion. We had a great start to that second season and didn’t lose for twelve games. We got promotion and that was my first full season as a manager, so it was a big moment for me. The next season we were in the Championship, and you have to reassess and be realistic about what you can achieve as a newly promoted team – but we managed to finish ninth and were only three points off the play-offs. The season after I knew there were rumblings in the background about the club getting a new owner, and whenever there’s a change of ownership it’s very rare that you keep your job. It has happened, but it didn’t happen with me.’

I suppose I was fortunate, because although I managed for seventeen years I was never actually sacked. But for most managers the reality is that the sack is really just around the corner, and for managers in the Championship their average tenure is about eight months, which is staggering. Managing in the Premier League is one thing and it brings its own set of problems, but managing outside of it can be very different. There isn’t the money for clubs in the Championship or lower that there is in the Premier League, but everyone in the Championship would love to make that leap up to play with the elite and enjoy all the riches that come with it. As a consequence there’s enormous pressure on a lot of Championship managers to achieve that goal and win promotion.

‘The reality is that twenty-one teams in the Championship are going to fail every season,’ Chris points out. ‘Only three teams go up, and I think with lots of clubs short-termism comes into play. They want to get that success quickly, and maybe are not prepared to plan longer-term and build. I think as a manager you have a responsibility to try to bring young players through, to try to make that happen, but you also know that you’re not always going to get time. That’s the reality, and losing your job is something that every manager has to come to terms with. As a manager I think you should have a period of two or three months out of it when you lose your job. It gives you time to live your life a little bit, and mentally and physically get yourself back to where you should be because it’s a stressful job. The stresses of running a club and dealing with different personalities is very tough on an individual. I think you need that break before you go back in. You always want to do things better next time and hope the people you work for are in line with you.’

Being a manager is tough for anyone, and what you do in your job is always under the microscope. You operate in an extremely public arena and your work is judged on a very regular basis. Chris is one of the few black managers we have in this country and as such I wondered if that brought any added pressures to what is already a very difficult job.

‘To be honest I think the added pressure will always be there because it’s such a big topic,’ he says. ‘It’s an area where people have always wondered, “Why hasn’t it happened more?” So I understand the position I’m in, and a few people who have been before me and who are in positions now. I understand how it is with regard to how I carry myself. I understand that people are looking up to me to see how I handle it, and that it may encourage others to become managers. Being a manager is a huge job regardless, but I’ve got a second job. I understand that to make a difference I have to do my job well. It may not always end up the way you want it to at a club, but as long as you’ve made a difference when you’ve been a manager at your particular club then that’s good. I know people talk about the “Rooney Rule”. That works – or has been working – in America. Maybe they’ve just got a bit more history in other sports like basketball; it’s kind of been ingrained in the mindset of people for a long time there. We have to start somewhere and that somewhere is now. I think there are more black players thinking about coaching and managing, but I think maybe in the past there weren’t too many people to look up to.’

Whenever I get asked about the job by a young manager and about how they should approach it, I always say that the first thing to do is get the expectation level right, from the chairman and from the board. What do they think would be a successful year on the budget they are going to give the manager? I think managing in the Premier League is totally different to managing in the Championship. The chances that come along for a young manager are few and far between. If you don’t give it everything you’ll regret it forever. You have to be totally consumed by it. As a footballer Chris played in all the divisions as well as for England. He had the drive, ability and dedication he needed when he was playing, and hopefully those same qualities will see him have a long and successful career as a manager.

Chapter 2

Player (#u5dbca813-44d2-5c6a-85f0-2694964d15b0)

Harry Kane, Mark Noble

When fans go to watch their favourite teams and see the players walk out onto the pitch before the start of a game they are probably unaware of the different paths those footballers may have taken to get to that point in their lives. Being a first-team player doesn’t just happen, and it certainly doesn’t happen overnight. It has usually involved years of dedication, years of having to prove themselves and years of having to cope with the ups and downs the game will inevitably throw at anyone who wants to earn their living as a professional footballer.

Becoming a regular Premier League player can now offer financial rewards beyond most fans’ dreams. Players are lucky to be playing in an era that offers these rewards, but they don’t just walk into a top club’s first team. There’s a very long road that they have to travel that will test them mentally and physically, and even when they are part of a first team, it’s up to them to keep proving themselves week in, week out. Very few players can afford to feel totally secure about their place in a team. Of course, you’d expect Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo to be the first name on the team sheet each week, but even they are not immune to injuries, and an injury can not only mean time out of a side – it can, in some sad cases, mean the end of a career.

Top players these days are the new rock or movie stars. They become household names, and are on the backs – and fronts – of newspapers. A lot of players get stick for the amount of money they earn and for not having the connection with the fans that players in earlier eras perhaps had. It’s true that some of them don’t do themselves any favours with the way they behave on occasion, but they are by no means the majority; a lot of players are hard-working, decent individuals who recognise how fortunate they are to be playing at a time when the game is awash with money for those who reach the top.