По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

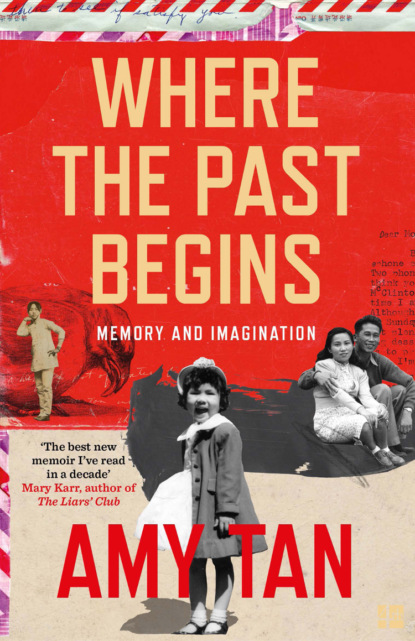

Where the Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Interlude – The Unfurling of Leaves

Interlude – The Auntie of the Woman Who Lost Her Mind

CHAPTER SIX – Unstoppable

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Twenty-Four

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Quirk – Time and Distance: Age Sixty (#litres_trial_promo)

IV. UNKNOWN ENDINGS

CHAPTER SEVEN – The Darkest Moment of My Life

Quirk – Nipping Dog

CHAPTER EIGHT – The Father I Did Not Know

Quirk – Reliable Witness

V. READING AND WRITING

Interlude – I Am the Author of This Novel

CHAPTER NINE – How I Learned to Read

Quirk – Splayed Poem: The Road

Quirk – Eidolons

CHAPTER TEN – Letters to the Editor

CHAPTER ELEVEN – Letters in English

Quirk – Why Write?

VI. LANGUAGE

CHAPTER TWELVE – Language: A Love Story

Quirk – Intestinal Fortitude

CHAPTER THIRTEEN – Principles of Linguistics

Epilogue – Companions in the House

Acknowledgments

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Amy Tan (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ubd66489a-40f1-517b-b0b7-a99d88cec6c0)

WHERE THE PAST BEGINS (#ubd66489a-40f1-517b-b0b7-a99d88cec6c0)

In my office is a time capsule: seven large clear plastic bins safeguarding frozen moments in time, a past that began before my birth. During the writing of this book, I delved into the contents—memorabilia, letters, photos, and the like—and what I found had the force of glaciers calving. They reconfigured memories of my mother and father.

Among the evidence were my parents’ student visas to the United States, letters from the U.S. Department of Justice regarding their deportation, as well as an application for citizenship. I found artifacts of life’s rites of passage: wedding announcements, followed soon by birth announcements, baby albums with tiny black handprints and downy locks of hair; yearly diaries; the annual Christmas letters with complaints and boasts about the children; floral-themed birthday and anniversary cards; a list of twenty-two people who had given floral contributions for my father’s funeral; and condolence cards bearing illustrations of crosses, olive trees, and dusk at the Garden of Gethsemane. There was also a draft of a surprising mature-sounding letter that I had written to serve as the template my mother could copy to thank people for their sympathy.

Perhaps the most moving discoveries were the letters to me from my mother and the letters to my mother from me. She had saved mine and I had saved hers, even the angry ones, which is proof of love’s resilience. In another box, I found artifacts of our family’s hard work: my mother’s ESL essay on becoming an immigrant and her nursing school homework; my father’s thesis, sermons, and his homework for a graduate class in electrical engineering; my grade school essays and my brother Peter’s history compositions; the report cards of Peter, John, and me, from kindergarten through high school, as well as my father’s college records. In different files, I recovered my father’s and mother’s death certificates. I haven’t come across Peter’s yet, but I found a photo of him in a casket, his sixty-pound body covered by a high school letterman jacket, but with nothing to conceal the mutilation of his head by surgeries and an autopsy. So now I have to ask myself: What kind of sentimentality drove me to keep that?

Actually, I never throw away photos, unless they are blurry. All of them, even the horrific ones, are an existential record of my life. Even the molecules of dust in the boxes are part and parcel of who I am—so goes the extreme rationale of a packrat, that and the certainty that treasure is buried in the debris. In my case, I don’t care for dust, but I did find much to treasure.

To be honest, I have discarded photos of people I would never want to be reminded of again, a number that, alas, has grown over the years to eleven or twelve. The longer I live the more blurry photos I’ve accumulated, along with a few sucker punches from people I once trusted and who did the equivalent of knocking me down to be first in line at the ice-cream truck. Age confers this simple wisdom: Don’t expose yourself to malarial mosquitoes. Don’t expose yourself to assholes. As it turns out, throwing away photos of assholes does not remove them from consciousness. Memory, in fact, gives you no choice over which moments you can erase, and it is annoyingly persistent in retaining the most painful ones. It is extraordinarily faithful in recording the most hideous details, and it will recall them for you in the future with moments that are even only vaguely similar.

With only those exceptions, I have kept all the photos. The problem is, I no longer recognize the faces of many—not the girl in the pool with me, or three out of the four women at a clothes-swap party. Nor those people having dinner at my house. Then again, I have met hundreds of thousands of people in my sixty-five years. Some of them may have even been important in my life. Yet, without conscious choice on my part, my brain has let a lot of moments slide over the cliff. While writing this memoir, I was conscious that much of what I think I remember is inaccurate, guessed at, or biased by experiences that came later. If I were to write this same book five years from now, I would likely describe some of the events differently, either because of a change of perspective or worsening memory—or even because new evidence has come to light. That is exactly what happened while writing this book. I had to revise often as more discoveries appeared.

I used to think photographs were more accurate than bare memory because they capture moments as they were, making them indisputable. They are like hard facts, whereas aging memory is impressionistic and selective in details, much like fiction is. But now, having gone through the archives, I realize that photos also distort what is really being captured. To get the best shot, the messiness is shoved to the side, the weedy yard is out of the shot. The images are also missing context: the reason why some are missing, what happened before and after, who likes or dislikes whom, if anyone is unhappy to be there. When they heard “cheese,” they uniformly stared at the camera’s mechanical eye, and put on the happy mask, leaving a viewer fifty years later to assume everyone had a grand time. I keep in mind the caveat that I should question what I see and what is not seen. I use the photos to trigger a complement of emotional memories. I use a magnifying glass to look closely at details in the black-and-white images in sizes popular in the 1940s and 1950s—squares ranging from one and a half to three and a half inches. They document a progression of Easter Sundays after church and the annual mauling of Christmas presents, which were laid underneath scraggly trees or artificial ones, in old apartments or new tract homes. Some of these photos refuted what I had believed was true, for example, that our family owned no children’s books, except one, Chinese Fairy Tales, illustrated by an artist who made the characters look like George Chakiris and Natalie Wood from West Side Story. A photo of me at age three shows otherwise: I am mesmerized by the words and pictures in a book spread open in my lap. In other photos of that same day, there is evidence of presents of similar size waiting to be ripped open. I had not known this when I wrote the piece “How I Learned to Read.” But it all makes sense that I would have been given books by family friends, if not by my parents. As a writer, I’m glad to know that my grubby little paws were all over those pages.

I came across many photos of me from the ages of one to five looking flirtatiously photogenic: perched in the crook of a tree, looking up from a wading pool, holding a cup with two hands, giving myself a hug, or grinning at the bottom of a playground slide. My father was an amateur photographer with a prized Rollei camera. He was no doubt giving me suggestions on how to arrange myself, praising me for remaining still, and telling me how pretty I looked, words I would have taken as a reward of love not given to my mother or brothers.

The oldest and rarest photos are in large-format albums. After seventy years, the glue has flaked off the bindings and the rusty rivets have lost their heads. The paper corner brackets that held the photos in place have fallen off, and the photos lie loose between thick black pages. Some of the studio photos taken over a hundred years ago are the size of postage stamps, which was why I did not realize they were of my grandmother until six years ago, when I placed a magnifying loupe over the sepia images.

One album holds photos my father took of my mother when they became secret lovers in Tianjin in 1945. He had arranged an artful collage: a large photo of my mother is in the center and smaller ones of himself surround her, as if to say that she is the center of his universe. My father also took many photos of Peter, the firstborn. I found multiple copies of the same photos, suggesting he sent them to friends or handed them out at church. My younger brother, John, received short shrift. Very few are of him alone.

By the early 1960s, my father stopped taking artfully posed photos with his Rollei. He switched to a Brownie camera for snapshots at birthday parties or when relatives or family friends came a long distance to visit us. There are fewer photos of my brothers and me when we were no longer cute and huggable; our limbs had elongated and turned knobby and our faces were sweaty, pimply, and darkened by the sun. In one, I am wearing white cat’s-eye glasses. My hairstyle looks like an explosion of black snakes, the aftermath of a novice beautician’s first attempt at giving a perm. My nose is bulbous, my cheeks are balloons, and my legs are thick and shapeless. That was how I saw myself. I browse through more images, seeking clues of the start of illness in our family. In one of the last photos of my father, he appears to have aged a great deal in just one year. His face looks tired and puffy. He has lost half of his eyebrows, which makes him look less vivid. After he died, there were few posed photos, not even for Lou’s and my wedding, aside from a dozen snapshots taken by friends and family members with disposable cameras. How lucky I am that my father, the amateur photographer with his prized Rollei camera, left behind such a rich pictorial history of our family.

In another bin, I found my first attempts at fiction writing, starting at the age of thirty-three. I saw layers of abandoned novels from over the last twenty-seven years, distressing pages I had not looked at since the awful day when I knew in the hollow of my gut that the novel was dead and that no further revisions or advancement of the narrative would save it. I had long since gotten over being heartsick about them. Nowadays, I let go of pages much more easily. That’s a necessary part of finding a story. Yet I had my trepidations about rereading those abandoned pages. When I did, I saw again the flaws that doomed them. But I was also happy to remember those fictional places where I had lived for months or years, while sitting long hours at my desk. I was still interested in the characters and their personalities. There is much in these stories I am still fond of. I never lost them. They are there, but just for me.

I took out a random assortment of childhood memorabilia and felt fond and strange emotions handling these objects that had once meant so much. I was aware that my fingerprints overlay those I had left as a child. There was residue of who I was in these objects. I was the girl who secretly wanted to be an artist. At eleven, the drawing of my cat lying on her back was the best I had ever done. At twelve, the best was a portrait of my cat soon after she was killed. I saved my brother’s scrawled science project notes on the care, feeding, breeding, and deaths of his guinea pigs. I kept his Willie Mays baseball mitt, which is no longer pliable. I kept two naked dolls with articulated joints whose eyes open and close, but not in synchrony, giving them a drunken cock-eyed expression. I remembered why I kept the pink WHILE YOU WERE OUT message slip on which the high school secretary had written that my brother Peter was doing well after brain surgery. I thought then that if I threw it away, he would die. So I kept it, but he died anyway.

This past year, while examining the contents of those boxes—the photos, letters, memorabilia, and toys—I was gratified to learn that many of my childhood memories were largely correct. In many cases, they returned more fully understood. But there were also shocking discoveries about my mother and father, including a little white lie they told me when I was six, which hugely affected my self-esteem throughout childhood and even into adulthood. The discoveries arranged themselves into patterns, magnetically drawn, it seemed, to what was related. They include artifacts of expectations and ambition, flaws and failings, catastrophes and the ruins of hope, perseverance and the raw tenderness of love. This was the emotional pulse that ran through my life and made me the particular writer that I am. I am not the subject matter of mothers and daughters or Chinese culture or immigrant experience that most people cite as my domain. I am a writer compelled by a subconscious neediness to know, which is different from a need to know. The latter can be satisfied with information. The former is a perpetual state of uncertainty and a tether to the past.

The original idea for this book had nothing to do with excavating artifacts or writing about the past. My editor and publisher, Daniel Halpern, had suggested an interim book between novels, based on some of the thousands of e-mails I bombarded him with during the writing of The Valley of Amazement. I thought it was a bad idea, but he convinced me otherwise with reasons I no longer recall but likely included words any writer would like to hear over a glass of wine: “compelling,” “insightful,” “easy to pull together.” I plowed into the e-mails to see what might be usable. The earliest were the e-mails we exchanged after we met for the first time over drinks to discuss the possibility of working together on my next novel. My e-mails were not carefully composed. They were dashed off with free-form spontaneity, a mix of rambling thoughts off the top of my head, anecdotes of the day, and updates on my dogs and perfect husband. In contrast, Dan’s e-mails were thoughtful and more focused on my concerns, although they also included notes about Moroccan cuisine. He sometimes responded to my offhand remarks with too much care, thinking I had expressed serious wringing of my soul. After six months of wading through our e-mails, I knew I had been right from the start. This was a bad idea for a book. The e-mails would not add up to an insightful book on anything to do with writing. It could serve as a paean to procrastination. I now faced writing a real book.

Unlike those e-mails, I could not write whatever came to mind for a book and consider it good enough to show. Normally, it would take me a week to produce a page that I felt was good enough to keep. Upon rewriting the book, that page and those surrounding it would be cut. While crafting my sentences, I would be aware that an editor expects that a submitted manuscript will be clean, polished pages. [ed. note: Not this editor.] My awareness of this fact would lead me to revise endlessly and self-consciously, steamrollering over characters and the freshness of scenes until they were flat and moribund. That had been a major reason each novel had taken longer to finish. After a year of trying a mushy bunch of other ideas, I finally came up with a plan. What had enabled me to write those thousands of e-mails was spontaneity. If I applied that to writing a book, I would be able to finish quickly. I would not think too far ahead about what to write; I would simply write wherever my thoughts went that day and allow for impulse, missteps, and excess. Revision and excision could happen later. To ensure spontaneity, I made a pact with my editor: I would turn in a piece, fifteen to twenty-five pages every week, no excuses. [ed. note: I should add, I told my author that any pages beyond the required fifteen would not go as a credit for the next installment. We also agreed on some vocabulary that could not be used during the march toward completion. They were: chapter, essay, memoir (which became my secret), finished manuscript, the new book, and deadline. The pieces of prose became known as cantos, harmless enough when writing prose.] Since I would have no time to revise, Dan would need to understand that he would receive true rough drafts, written off the top of my head, and thus, they would contain the traits of bad writing, garbled thoughts, and clichés. To minimize self-consciousness, I asked that Dan not provide comments, good or bad, unless he thought I was veering seriously off track and writing a book he would be insane to publish. [ed. note: Which I have never done.]

What editor would not be happy to be the enforcer of such a plan? What sane writer would not later realize that schedule to be ulcerating and impossible? [ed. note: Honestly, it didn’t seem that onerous to me.]

Even so, I did not miss a deadline, except one. The last. [ed. note: Technically, she was always a day late, using the excuse of PST, to protest her PTSD.] It was the Monday after the 2016 presidential election, and I felt lost, unable to focus. For the last piece, I chose the only subject that was relevant to me at the moment: the election and how my father would have voted. When I finished, I had both a book and an ulcer.

I wrote more than what is in this book. Free-form spontaneity had given rise to a potluck of topics and tone. Some were fun, like my relationship to wildlife and, in particular, a terrestrial pest from Queensland, Australia, a newly identified species of leech, Chtonobdella tanae, that bears my name. I also wrote a piece on the magnificent short story writer Mavis Gallant, our conversations over ten years of lunches and dinners in Paris, the last one spent in her apartment, where I read aloud to her for hours after a lunch of blinis and smoked salmon. I also considered using a few pages of cartoons—doodles drawn when I was bored at a conference—which I called “a graphic memoir of my self-esteem.” In the end, as the shape of the book emerged, Dan and I agreed on the ones I should keep. I had only one concern: what remains might give readers the misperception that I am cloistered in a lightless room with buckets of tearful reverie. There is reverie, but the room is surrounded by windows and is so bright I have to wear sunscreen when I write.

Since this is an unintended memoir, I thought it would be appropriate to include writings from my journals. I gleaned entries that reflect the spontaneity and seeming randomness of ideas that characterize how I think. They are also in keeping with the nature of the other pieces in this book. I call the longer, anecdotal entries from my journals “interludes.” I call the shorter entries “quirks.” They are quirky thoughts from the top of the head, or quirky things I have seen or heard, or quirky remnants of dreams. For writers, quirks are amulets to wonder over, and some have enough strangeness in them to become stories.