По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

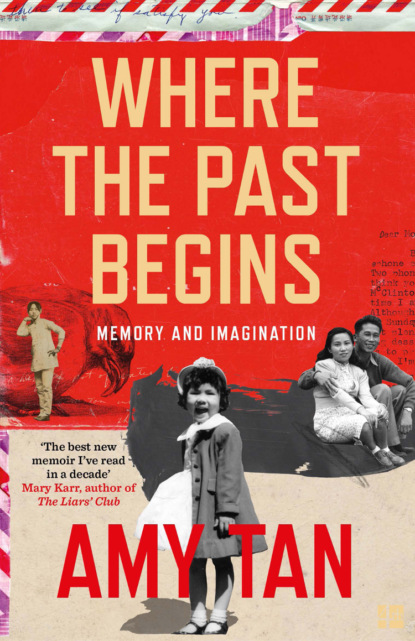

Where the Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Peter never bragged that he was smarter. When I could not do whatever he was doing, he helped me. He taught me how to catch a ball with a mitt, how to throw a newspaper, how to ride a bike hands free, how to climb over a fence or under barbed wire, how to breed guinea pigs, how to collect baseball bubble gum cards, and how to look up words in a thesaurus. He taught me Mad magazine jokes, the names of the most popular songs, and how to spy on our neighbors when they were having a fight. Whatever game he was playing, he let me play. He was Davy Crockett in his fake coonskin cap. I was the Indian maiden. When he received a Lionel train set for Christmas, he assembled the control box and connected the electrical wires. He let me help by connecting the tracks and setting up the plastic scenery. In high school, he ran for treasurer, so I ran for secretary. He let me read his books, the primers in grade school, and later, the novels in high school.

Oakland, 1955. Playmates: Peter, five, and me, three.

I always believed he was better in everything and always would be, and not simply because he was eighteen months older. It was because of what my parents said about Peter, openly commenting on his brilliance. Just the other day, I found my first grade report card and saw what my father had written to my teacher. His praise of me was offset by his higher praise of Peter, an opinion that has remained since childhood as indelible in my mind as the ink in his note.

Amy used to have a sense of inferiority over her brother’s out-shining intelligence. This report gives her a big boost in her morale. She will need our constant encouragement as well as yours to keep her stride in such a high-spirited rhythm.

I actually don’t recall feeling inferior to Peter, at least not in a painful way. I simply accepted that he was smarter. I suffered no sense of inadequacy around other children my age. My parents and theirs would compare us in various ways. I weighed nine pounds and eleven ounces at birth, destined from the start to be the reigning champion for years in the categories of height, weight, and the speed in which we outgrew shoes. And I remained the heavyweight among the skinny children of family friends all the way until my first year in college, when I was diagnosed with a thyroid disorder and rapidly lost thirty pounds once I was treated. Last year, I winced when my parents’ friends told me with good humor about the many boasts they endured hearing whenever our families gathered together for dinner: “Peter is a genius,” or “Amy’s teacher said she reads with great expression.”

From a child’s point of view, I thought that how I was judged each day determined how much love I would receive. A smarter child would be better loved, but so would a sicker one. I remember that I competed for expressions of love—for special attention that came in the way of smiles, or being invited to watch my mother get ready for a party, or standing balanced on the soles of my father’s feet, or being given an early taste of whatever special dish my mother was cooking. I was deemed lovable for quietness, neatness, good manners, and a happy face. I was more lovable when I was feverish but not when I threw up, more lovable if I did not cry when a needle went in my arm, but not so lovable when I had scraped my knee doing something forbidden. One time I won the cooing praise of my mother for simply going to bed early without being told to do so. To remain praiseworthy I pretended to be asleep. I pretended so well, my mother turned off the light and closed the door, and then I sat up in tears, listening to other children laughing and shouting in the other rooms. I would draw pictures to win praise from teachers, especially when starting at a new school. I recall my shock and disappointment that the drawing of another kindergartner had been selected to hang in the principal’s hallway display window. Her drawing was terrible. It looked like she had scrawled on the paper with crayons stuck up her nose. My drawings were realistic, meaning: the people had feet and the houses had doors.

During childhood, I believed there were times when my mother disliked me, even hated me. Love was not constant. It varied in amount. It was removable. My insecurity about love was no doubt amplified by my mother’s threats or attempts to kill herself whenever she was unhappy with my father, her children, or her lot in life.

The good parent today may think it’s terrible for a child to live with uncertainty. But how can any parent prevent impressionable children from wondering where they stand in comparison to others? There are a hundred ways children are judged every day, from the moment the household awakens—how noisy the child is, how quickly or slowly the child eats breakfast or ties his or her shoes. And, as a parent, you cannot ensure popularity on the playground or how a teacher grades your child. You can’t change birth order and the fact that your brother was the firstborn son and the sole object of affection of newly besotted parents, and that he would later be regarded as your leader and protector. When my younger brother came along, like many middle children, I was jostled about in an evolving and changeable position in the new family order. The day John was born, I sat on the stoop in new Chinese pajamas embroidered with a hundred children, waiting anxiously for my mother to return to me. A family friend tried to soothe me and coax me into playing with her daughter. I would not budge from my spot on the stoop, the place where my mother had left me.

My little brother, John, who was nicknamed “Didi,” received love whenever he cried. He cried when his photo was taken, or when he was seated apart from our mother. He would cry when Peter and I would not let him play with our toys. He was not required to follow in Peter’s and my fast-paced footsteps. No overt demands or comparisons were made that might cause him to have a sense of inferiority. He was not told he should aim to become a doctor. Where were the impossible goals, the anxiety-inducing predictions? “Whatever will be will be” was my parents’ plan for him. They were never lackadaisical about anything to do with Peter or my education—or about anything, for that matter. But Didi could do no wrong. When my parents caught him eating gum he had peeled off the sidewalk, Peter and I were to blame for not watching him more carefully. When he broke our toys or stole our Halloween candy, our parents said that we should have shared instead of being selfish. Our parents unintentionally seeded Peter’s and my resentment toward our younger brother. Didi always got us in trouble, and we avoided him as much as possible.

My mother told me when I was an adult that she and my father treated John differently because they felt guilty that they spent relatively little time with him. They neglected him, she said. With Peter and me, they had been fully devoted from the start of our lives. They took us to parks, pointed out errors, helped us with our homework, monitored our progress, accompanied us to the library, and gave us piano lessons. As the years went by, my father became increasingly busy. He was simultaneously a full-time electrical engineer, a graduate student, a substitute Baptist minister, and an entrepreneur who had the same aspirations of many Silicon Valley engineers in the 1960s who were starting their niche companies in a garage. My mother had a full-time job as an allergy technician and ran a home business selling wigs. They were too tired to goad yet another child to improve his grades and practice the piano. My father did not spend hours helping Didi learn all twelve multiplication tables in one night, as he did with me. He was not forced to learn calligraphy in the second grade, as I was, as a method for improving penmanship. They allowed him to watch cartoons for hours as he lay splayed across the sofa, wrapped in his ratty blanket. My parents simply wanted John to feel loved and happy in a more expedient way.

My resentment toward my little brother changed during the year both of us stood on the sidelines, largely invisible, during the twelve months when both Peter and my father were dying of brain tumors. Family, friends, ministers, and church members surrounded our parents, prayed for miracles, spoke to our comatose brother, listened to my father recite the latest doctor’s report, sat with them in the hospital during each surgery, and laughed and cried as they recounted anecdotes of happier days. My mother saw every involuntary twitch of my comatose brother as meaningful. That year, they paid little attention to anything John and I did. He and I were equally neglected, equally criticized for not being helpful during crisis, equally buffeted by our mother’s depression, equally uncertain about her sanity when she brought in teams of faith healers and karma adjusters. We were equally scared when our mother wondered if there was a curse that would kill all of us. Who was next? When we complained of headaches or stomachaches, we were hauled down to the hospital for tests. We did not know how to grieve. We could not be crazy like our mother.

John and I survived that year of failed miracles. With my father gone, we stopped saying prayers at the dinner table. Our mother’s will to live collapsed and surged, from day to day. She would weep and ask aloud, “Why did this happen?” and then count out the imagined reasons. At other times, she was seized with a manic outpouring of ideas for our future—a restaurant, a souvenir shop, going to Taiwan so John and I could learn manners and to speak Chinese, or moving to Holland, simply because it was clean. Only we understood all the ways our family had fractured and why our mother would never heal. It was both natural and necessary that John and I became compatriots who could depend on each other for the rest of our lives.

Easter 1959: In the park after church.

My parents loved their children so much they wanted us to have the best opportunities an immigrant family could find. That required having the best models for success. One was Albert Einstein, who had also been an immigrant. I can’t imagine my parents truly believed we could be as smart as Einstein. But why not aim high and then fail just a little? That was their thinking. The only glimmer of Einstein they saw in me was his well-known trait of daydreaming and ignoring those around him. They had read a story that when Einstein was off in his own little world, his mind was actually exploding with ideas. My mind was not. I was not paying attention.

There was another Albert—Dr. Albert Schweitzer, who had the best morals. He won a Nobel Prize for having gone into the jungles of Africa, where he risked life and limb to cure gaunt-faced children of terrible wasting diseases. My father, a minister, also cited him as one of the highest examples of a good Christian. Goodness would not have motivated me to be like Dr. Schweitzer. The magazine stories about his heroism included photos of his patients’ crusted feet eaten away by leprosy. Dr. Schweitzer’s work was not suitable for a child with precocious anxiety and a morbid imagination.

The other model of success was musical. Mozart was the standard-bearer for many ambitious parents, ours included. My mother told me that Mozart started composing when he was five. No coincidence that I was five when she said that. That was also when a luminous black piano, a Wurlitzer spinet, arrived at our house and took its place along the entire length of a wall in our small living room. The Wurlitzer transformed our lives all at once. Our parents told us that the piano cost a lot of money, and this made me believe we had suddenly become rich. My mother had always complained that we were poor, in part because we gave away so much money. My father tithed 10 percent to the church and also sent money to his brothers and their families, who were refugees in Taiwan. We were shown photos of their sun-browned faces to make us proud to be good-hearted children. We also had to take care of my mother’s half brother and his family, who had left a life of wealth and privilege and arrived in the United States, unable to speak English, and unaccustomed to doing the kind of menial work that many Chinese immigrants had to do. They came during a time when my mother was attending nursing school and working part time in a hospital, a job that required her to empty bedpans, change soiled sheets, and wash people’s bottoms. One time, she had to listen to a newborn baby cry unceasingly. It had been born without an anus, she said. They could not feed it. She heard that baby cry throughout her night shift. It was agonizing. The next night, it was still crying. The following night, she heard no crying. She told us horror stories like that to show how much hardship she had to endure for our sake. She spoke of her life being so pitiful she almost “could not take it anymore.” When that expensive piano arrived, she was so happy I thought the pitiful days were over.

My mother warned us not to damage its perfect surface—no dings, dents, scratches, stains, or sticky fingerprints. The bench was also very expensive, she said, and we were scolded for sliding across with bare legs to make squeaky farting sounds. She became the detective who matched fingerprints to culprits. She was the terrifying interrogator when the first scratches appeared. Who did this? Who? When no one confessed, we were all sent to bed without dinner. This instrument, so powerful and yet so fragile, was now our mother’s most prized possession, and she let us know often that she and my father had sacrificed a great deal in coming to America so that we children could have a better life, which included learning to enjoy music.

1955: Me at age three, posing for my father’s Rollei.

I did not understand until I was an adult what she meant by “sacrifices.” They were all that she had left behind in Shanghai, where she had had a life of privilege, starting from the age of nine, when her widowed mother married the richest man on an island outside of Shanghai. She went from being the honorable widow of a poor scholar to a wealthy man’s fourth wife—one of his concubines, which made her a woman at the lower end of society. According to one version of clan history, her family had expected her to remain a widow, and thus she disgraced them all by remarrying. But had she not married, she would have had to depend on the largesse—or rather, the miserliness—of her opium-addicted older brother. Another version cast her as the victim of a rape by the rich man, which resulted in pregnancy. In less than a year, after she gave birth to a son, my mother’s mother was dead. One side of the family said she swallowed raw opium to end her shame as a concubine. The other side related it as an accident. My mother believed a bit of both versions. She said that her mother found it unbearable that she had descended to being the lowly concubine in a household of other numerical wives. So she made the rich man promise that if she gave birth to a son, he would let her live in her own house in Shanghai. He agreed. My mother was the only one who heard the deal had been struck. She saw her mother’s mood change in talking about their return to Shanghai. Life on the island was boring, she complained. But when the son was born, the rich man’s promise evaporated. My mother witnessed her mother’s fury when she learned she had been fooled. To teach her husband a lesson, she swallowed opium. She had only meant to scare him, my mother explained. Her mother never would have intentionally left her, her nine-year-old daughter, alone, an orphan. “She loved me too much to do that. She died by accident.” But there were a few times when she acknowledged that her mother killed herself because “she could not take it anymore.” Sometimes she felt the same, she would say.

My young mother remained in the mansion after her mother died. The rich man felt remorseful and posthumously revered his fourth wife as the mother of his son. In death, her position in the house was unassailable. The rich man promised to treat my mother as his own. He gave her a new name to reflect her official attachment to the family. He sent her to a private school for girls and paid for piano lessons. He bought her pretty clothes and a Bedlington terrier. My mother said that her stepfather was fond of her—he even let her eat with him, while everyone else had to sit at another table. Yet her feelings toward him remained conflicted. She blamed him for her mother’s death—first, for making her his concubine, and second, for breaking his promise. I imagine she called him “Father” out of respect, but whenever she spoke about him to me, she did not describe him as either her stepfather or her mother’s husband. She used his full name. She did not refer to the children of his other concubines as sisters or brothers. She referred to them by name and whichever number concubine was their mother. “The number two daughter of the number three wife.” Although she lived in the mansion while growing up, she told me she never felt she belonged. She was the daughter of a concubine who had killed herself, who had cast a shadow on the house. Relatives reminded her that she was lucky she was allowed to live in that house since she was not blood-related to the rich man. My mother said they reminded her so often she knew they were saying she did not really deserve to be there. “I was alone with no one to love and guide me, like I did for you,” she said. Without a mother to guide her, she did not recognize that the man who wanted to marry her was evil and would nearly destroy her mind.

I am guessing she was eighteen or nineteen when she married. She described herself as naive and stupid. He was the eldest of the second richest family on the island, a family of scholars. His father was the rich man’s business partner. He had also trained to be a pilot, one of an elite team, which made him a celebrity hero with a status equal to a movie star. He was supposed to marry the rich man’s eldest daughter, my mother said. It was to be an arranged marriage, the prestigious union of two wealthy families of high society. But the pilot wanted my mother, the prettier one, the daughter of the concubine who had killed herself. Everyone told her it was a good opportunity and she was lucky the man wanted her. “Why do you want to be pretty?” my mother said when I cried one day because I feared I was ugly. “Being pretty ruined my life.”

As soon as they married, her husband told her he had no intention of giving up his girlfriends, one of whom was a popular movie star. He brought women home almost every night. “That bad man said I should share the bed with them,” she said. “Can you imagine? I refused and that made him mad. He was mad? What about me?” “That bad man was also a gambler who spent my dowry. That bad man was no hero. He was a coward. During a big battle, many pilots died. But he turned his plane around and claimed he got lost.” Over the fourteen-year course of their marriage, she gave birth to a son, three daughters, and a ten-pound stillborn daughter whose skin was blue. (That stillborn half sister lives in my imagination as an angry-looking baby the color of the sea.) When my mother’s son died of dysentery at age three, my mother was in such despair over her life that she said as she cradled him, “Good for you, little one. You escaped.” Even after she attempted suicide, her husband refused to let her go. She was his property. He could torment her, slap her, or put a gun to her head whenever she refused to have sex with him.

A few years ago, at a family dinner, a distant cousin I had never met said to me, “Your mother had many boyfriends in China.” Another woman, also a stranger to me, said, “Many.” They wore a look of bemusement. I was shocked by what they had just divulged, not just the information but also the humor they took in telling me this. Had my mother been alive, she would have been propelled into a suicidal rage. I wanted to defend her. Yet I was also guilty of wanting to know more. Was it true? Did she have lovers? If so, who were those men? Did they love her? Did she love any of them? I did not ask, and they said no more.

Knowing my mother, I could imagine her taking lovers to spite her philandering husband. She had never been passive in expressing anger. I could also imagine another reason: she felt she belonged to no one. She wanted someone to love her. I also knew for certain that she had one lover while she was still married: my father. They had met around 1939 or 1940 when they both took a boat leaving out of Hong Kong. An uncle, my father’s brother, was on the same boat and gave me an account. My father was on his way to Guilin, where he worked as a radio engineer at a large radio factory, and my mother was going to Kunming, where her pilot husband was based. My uncle said sparks flew between my mother and father right from the start. He said she was beautiful and lively, and he wished that my mother had taken an interest in him instead of my father. Neither my father nor he knew at the time that she was married. Or, if my father had known, he did not share that with his brother.

Five years later, in 1945, my mother was in Tianjin with her sister-in-law, and she recognized the man coming toward her from the opposite direction. He was unmistakable—the downturned crinkle of his eyes, the wide snaggletooth grin, the wavy lock over his forehead. My mother recalled their meeting as fate. If she had come one minute later, she would have been on a train with her sister-in-law, on their way to Yanan. By then, my father was working in Tianjin for the U.S. Information Service Agency as a ham radio engineer. He spoke perfect English, dressed smartly, and was admired by both American and Chinese men and women as charming, handsome, and good humored. He played gentle pranks and laughed a lot. “He could have married any woman,” my mother emphasized. “They all wanted him, many mothers of many daughters. But he chose me.” When they began their affair she was twenty-nine years old and he was thirty-one.

I have many photos of them taken during their early romance. The look in her eyes is unmistakable. She wears a shy smile in the afternoon, a radiant one in the morning. I do not know how long they lived together in secret, but I imagine from different clothes she wore in those photos that it was long enough to go from a cooler season to a warmer one.

My mother’s husband, the celebrity war hero, was enraged that she had run away. He hired a detective, who put up her photo in every beauty salon. One day, when she walked out with her freshly styled hair, she was arrested and brought back to Shanghai. There she was put in jail in a common cell with prostitutes. The news came out in the gossip columns: the beautiful society girl who was unfaithful to her husband, the hero pilot. While she was in jail, awaiting trial, she attempted suicide. When she was told she could be released to go home before the trial, she said she preferred to remain in prison rather than risk being beaten by her husband. Even if she was released, where would she go? No one would have dared give her shelter, a relative told me. She had committed a serious crime and brought scandal on the family. Behind the scenes, the family of the wealthy man paid bribes to numerous people to ensure the charges would be dropped and that no more would be written in the gossip columns. She had no choice but to return to the home where her three daughters, husband, and his strong-willed concubine awaited her. At times, when she could not bear her life, she went to live with other relatives. Her husband would position their daughters below her window, where they would cry for her, begging: “Come back, Mama!” My half sister Jindo told me she cried the loudest. My other half sister, Lijun, was only four, and she recalls that she did not understand what was going on, except that her mother was too upset to take care of any of them.

1949. Enclosed: The diploma belonging to Tu Chuan that my mother used for her student visa.

My father remained in Tianjin, where he eventually worked with the U.S. Army Corps. He had already received acceptance letters in 1944 to study in the graduate program at both MIT and the University of Michigan. But wartime had made it impossible to leave. In 1947, he was hired by the American Council on Economic Affairs. He eventually got a visa to the United States as an “official with the Council on Economic Affairs,” and soon after he arrived, he applied for a student visa.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: