По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

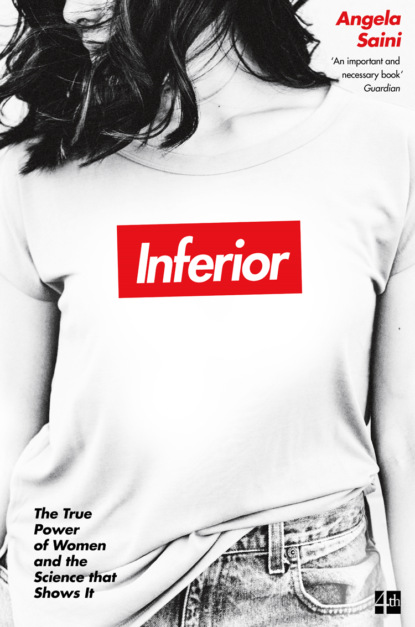

Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting The Story

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

To prove women’s inferiority, antifeminists began to draw not only, as before, on religion, philosophy and theology, but also on science: biology, experimental psychology and so forth.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

The University of Cambridge at the end of summer with the leaves going dry is as beautiful as it must have been when Charles Darwin was an undergraduate here in the early nineteenth century. Up in the quiet and high north-west corner of the university’s library, traces of him still exist. Seated at a leather-topped table in the manuscripts room, I’m holding three letters, all yellowing, the ink faded and the creases brown. Together they tell a story of how women were viewed at one of the most crucial moments of modern scientific history, when the foundations of biology were being mapped out.

The first letter, addressed to Darwin, is written in an impeccably neat script on a small sheet of thick cream paper. It’s dated December 1881 and it’s from a Mrs Caroline Kennard, who lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, a wealthy town outside Boston. Kennard was prominent in her local women’s movement, pushing to raise the status of women (once making a case for police departments to hire female agents). She also had an interest in science. In her note to Darwin, she has one simple request. It is based on a shocking encounter she’d had at a meeting of women in Boston. Someone had taken the position, Kennard writes, that ‘the inferiority of women; past, present and future’ was ‘based upon scientific principles’. The authority that encouraged this person to make such an outrageous statement was no less than one of Darwin’s own books.

By the time Kennard’s letter arrived, Darwin was only a few months away from death. He had long ago published his most important works, On the Origin of Species in 1859, and The Descent of Man, which came out twelve years later. They laid out how present-day humans could have evolved from simpler forms of life by developing characteristics that made it easier to survive and have more children. This was the bedrock of his theories of evolution based on natural and sexual selection, which blasted through Victorian society like dynamite, transforming how people thought about the origins of humankind. His legacy was assured.

In her letter, Kennard naturally assumes that a genius like Darwin couldn’t possibly believe that women are naturally inferior to men. Surely his work had been misinterpreted? ‘If a mistake has been made, the great weight of your opinion and authority should be righted,’ she entreats.

‘The question to which you refer is a very difficult one,’ Darwin replies the following month from his home at Downe in Kent. His letter is written in a scrawling hand so difficult to read that someone has copied the entire thing word for word onto another sheet of paper, kept alongside the original in the Cambridge University archives. But the handwriting isn’t the most objectionable thing about this letter. It’s what Darwin actually writes. If polite Mrs Kennard was expecting the great scientist to reassure her that women aren’t really inferior to men, she was about to be disappointed. ‘I certainly think that women though generally superior to men [in] moral qualities are inferior intellectually,’ he tells her, ‘and there seems to me to be a great difficulty from the laws of inheritance, (if I understand these laws rightly) in their becoming the intellectual equals of man.’

It doesn’t end there. For women to overcome this biological inequality, he adds, they would have to become breadwinners like men. And this wouldn’t be a good idea, because it might damage young children and the happiness of households. Darwin is telling Mrs Kennard that not only are women intellectually inferior to men, but they’re better off not aspiring to a life beyond their homes. It’s a rejection of everything Kennard and the women’s movement at the time were fighting for.

Darwin’s personal correspondence echoes what’s expressed quite plainly in his published work. In The Descent of Man he argues that males gained the advantage over females across thousands of years of evolution because of the pressure they were under in order to win mates. Male peacocks, for instance, evolved bright, fancy plumage to attract sober-looking peahens. Similarly, male lions evolved their glorious manes. In evolutionary terms, he implies, females are able to reproduce no matter how dull their appearance. They have the luxury of sitting back and choosing a mate, while males have to work hard to impress them, and to compete with other males for their attention. For humans, the logic goes, this vigorous competition for women means that men have had to be warriors and thinkers. Over millennia this has honed them into finer physical specimens with sharper minds. Women are literally less evolved than men.

‘The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shewn by man attaining to a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than woman can attain – whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination, or merely the use of the senses and hands,’ Darwin explains in The Descent of Man. The evidence appeared to be all around him. Leading writers, artists and scientists were almost all men. He assumed that this inequality reflected a biological fact. Thus, his argument goes, ‘man has ultimately become superior to woman’.

This makes for astonishing reading now. Darwin writes that if women have somehow managed to develop some of the same remarkable qualities as men, it may be because they were dragged along on men’s coat-tails by the fact that children in the womb inherit attributes from both parents. Girls, by this process, manage to steal some of the superior qualities of their fathers. ‘It is, indeed, fortunate that the law of the equal transmission of characters to both sexes has commonly prevailed throughout the whole class of mammals; otherwise it is probable that man would have become as superior in mental endowment to woman, as the peacock is in ornamental plumage to the peahen.’ It’s only a stroke of biological luck, he implies, that has stopped women from being even more inferior to men than they are. Trying to catch up is a losing game – nothing less than a fight against nature.

To be fair to Darwin, he was a man of his time. His traditional views on a woman’s place in society don’t run through just his scientific works, but those of many other prominent biologists of the age. His ideas on evolution may have been revolutionary, but his attitudes to women were solidly Victorian.

We can guess how Caroline Kennard must have felt about Darwin’s comments from the long, fiery response she sent back. Her second letter is not nearly as neat as her first. She argues that, far from being housebound, women contribute just as much to society as men do. It was, after all, only in wealthier middle-class circles that women tended not to work. For many Victorians, women’s incomes were vital to keeping families afloat. The difference between men and women wasn’t the amount of work they did, but the kind of work they were allowed to do. In the nineteenth century, women were barred from most professions, as well as from politics and higher education.

As a result, when women worked, it was generally in lower-paid jobs such as domestic labour, laundry, the textile industries and factory work. ‘Which of the partners in a family is the breadwinner,’ Mrs Kennard writes, ‘when the husband works a certain number of hours in the week and brings home a pittance of his earnings … to his wife; who early and late with no end of self sacrifice in scrimping for her loved ones, toils to make each penny.’

She ends on a furious note: ‘Let the “environment” of women be similar to that of men and with his opportunities, before she be fairly judged, intellectually his inferior, please.’

I don’t know what Darwin made of Mrs Kennard’s reply. There’s no more correspondence between them in the library’s archives.

What we do know is that she was right – Darwin’s scientific ideas mirrored society’s beliefs at the time, and they coloured his judgement of what women were capable of doing. His attitude belonged to a train of scientific thinking that stretched back at least as far as the Enlightenment, when the spread of reason and rationalism through Europe changed the way people thought about the human mind and body. ‘Science was privileged as the knower of nature,’ Londa Schiebinger explains to me. Women were portrayed as belonging to the private sphere of the home, and men as belonging to the public sphere. The job of nurturing mothers was to educate new citizens.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, when Darwin was carrying out his research, the image of the weaker, intellectually simpler woman was a widespread assumption. Society expected wives to be virtuous, passive and submissive to their husbands. It was an ideal illustrated in a popular verse of the time, The Angel in the House, by the English poet Coventry Patmore: ‘Man must be pleased; but him to please/is woman’s pleasure.’ Many thought that women were naturally unsuited to careers in the professions. They didn’t need to have public lives. They didn’t need the vote.

When these prejudices met evolutionary biology the result was a particularly toxic mix, which would poison scientific research for decades. Prominent scientists made no secret of the fact that they thought women were the inferior half of humanity, in the same way that Darwin had.

Indeed, it’s hard today to read some of the things that famous Victorian thinkers wrote about women and not be shocked. In an article published in Popular Science Monthly in 1887, the evolutionary biologist George Romanes, a friend of Darwin’s, patronisingly praises women’s ‘noble’ and ‘lovable’ qualities, including ‘beauty, tact, gayety, devotion, wit’. He also insists, as Darwin had, that women can never hope to reach the same intellectual heights as men, however hard they try: ‘From her abiding sense of weakness and consequent dependence, there also arises in woman that deeply-rooted desire to please the opposite sex which, beginning in the terror of a slave, has ended in the devotion of a wife.’

Meanwhile, in their popular 1889 book The Evolution of Sex, Scottish biologist Patrick Geddes and naturalist John Arthur Thomson argue that women and men are as distinct from each other as passive eggs and energetic sperm. ‘The differences may be exaggerated or lessened, but to obliterate them it would be necessary to have all the evolution over again on a new basis. What was decided among the prehistoric Protozoa cannot be annulled by Act of Parliament,’ they state, in an obvious dig at women who were fighting for their right to vote. Geddes and Thomson’s argument, stretched out over more than three hundred pages, and including tables and line drawings of animals, outlines how they see women as being complementary to men – as homemakers to the male breadwinners – but certainly not able to achieve the same as them.

Another example is Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton, remembered by history as the father of eugenics, and for his devotion to measuring the physical differences between people. Among his quirkier projects was a ‘beauty map’ of Britain, produced around the end of the nineteenth century by secretly watching women in various regions and grading them from the ugliest to the most attractive. Brandishing their rulers and microscopes, men like Galton hardened sexism into something that couldn’t be challenged. By gauging and standardising they coated what might otherwise have been seen as ridiculous enterprises with the appearance of scientific respectability.

Taking on this male scientific establishment wasn’t easy. But for nineteenth-century women – women like Caroline Kennard – everything was at stake. They were fighting for their fundamental rights. They weren’t even recognised as full citizens. It wasn’t until 1882 that married women in the United Kingdom were allowed to own and control property in their own right. And in 1887 only two-thirds of US states allowed a married woman to keep her own earnings.

Kennard and others in the women’s movement realised that the intellectual debate over the inferiority of women could only be won on intellectual grounds. Like the male biologists attacking them, they would have to deploy science to defend themselves. English writer Mary Wollstonecraft, who lived a century earlier, urged women to educate themselves: ‘… till women are more rationally educated, the progress of human virtue and improvement in knowledge must receive continual checks’, she wrote in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792. Prominent Victorian suffragists made similar arguments, using what education they were allowed to have to question what was being written about women.

The new and controversial science of evolutionary biology became a particular target. Antoinette Brown Blackwell, believed to be the first woman ordained by an established Protestant denomination in the United States, complained that Darwin had neglected sex and gender issues. Meanwhile, American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author of the feminist short story ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, turned Darwinism around to put the case for reform. She thought that half the human race had been kept at a lower stage of evolution by the other half. With equality, women would finally have the chance to prove themselves equal to men. She was ahead of her time in many ways, arguing against a stereotyped division of toys for boys and girls, and foreseeing how a growing army of working women might change society in the future.

But there was one Victorian thinker who took on Darwin on his own turf, writing her own book that passionately and persuasively argued on scientific grounds that women were not inferior to men.

‘It seemed clear to me that the history of the life on the earth presents an unbroken chain of evidence going to prove the importance of the female.’

Unconventional ideas can appear from anywhere, even the most conventional of places.

The township of Concord in Michigan is one of those places. Home to scarcely more than three thousand people, it’s an almost entirely white corner of America. The area’s biggest attraction is a preserved post-Civil War house covered in pale clapboard siding. In 1894, not long after this house was built, a middle-aged schoolteacher from right here in Concord published some of the most radical ideas of her age. Her name was Eliza Burt Gamble.

We don’t know much about Gamble’s personal life, except that she was a woman who had no choice but to be independent. She lost her father when she was two, her mother when she was sixteen. Left without support, she made a living by teaching at local schools. According to some reports, she went on to achieve impressive heights in her career. She also married and had three children, two of whom died before the century was out. Gamble’s life could have been mapped out for her, the way it was for most middle-class women of her time. She could have been a quiet, submissive housewife of the kind celebrated by Coventry Patmore. Instead, she joined the growing suffrage movement to fight for the equal rights of women, becoming one of the most important campaigners in her region. In 1876 she organised the first women’s suffrage conference in her home state of Michigan.

Gamble believed there was more to the cause than securing legal equality. One of the biggest sticking points in the fight for women’s rights, she recognised, was that society had come to believe that women were born to be lesser than men. Convinced that this was wrong, in 1885 she set out to find hard proof for herself. She spent a year studying the collections at the Library of Congress in the US capital, scouring the books for evidence. She was driven, she wrote, ‘with no special object in view other than a desire for information’.

Evolutionary theory, despite what Charles Darwin had written about women, actually offered great promise to the women’s movement. It opened a door to a revolutionary new way of understanding humans. ‘It meant a way to be modern,’ says Kimberly Hamlin, whose 2014 book From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women’s Rights in Gilded Age America charts women’s responses to Darwin. Evolution was an alternative to religious stories that painted woman as merely man’s spare rib. Christian models for female behaviour and virtue were challenged. ‘Darwin created a space where women could say that maybe the Garden of Eden didn’t happen … and this was huge. You cannot overestimate how important Adam and Eve were in terms of constraining and shaping people’s ideas about women.’

Although not a scientist herself, through Darwin’s work Gamble realised just how devastating the scientific method could be. If humans were descended from lesser creatures, just like all other life on earth, then it made no sense for women to be confined to the home or subservient to men. These obviously weren’t the rules in the rest of the animal kingdom. ‘It would be unnatural for women to sit around and be totally dependent on men,’ Hamlin tells me. The story of women could be rewritten.

But, for all the latent revolutionary power in his ideas, Darwin himself never believed that women were the intellectual equals of men. This wasn’t just a disappointment to Gamble, but judging from her writing, a source of great anger. She believed that Darwin, though correct in concluding that humans evolved like every other living thing on earth, was clearly wrong when it came to the role that women had played in human evolution.

Her criticisms were passionately laid out in a book she published in 1894, called The Evolution of Woman: An Inquiry into the Dogma of Her Inferiority to Man. Marshalling history, statistics and science, this was Gamble’s piercing counter-argument to Darwin and other evolutionary biologists. She angrily tweezed out their inconsistencies and double standards. The peacock might have had the bigger feathers, she argued, but the peahen still had to exercise her faculties in choosing the best mate. And while on the one hand Darwin suggested that gorillas were too big and strong to become higher social creatures like humans, at the same time he used the fact that men are on average physically bigger than women as evidence of their superiority.

He had also failed to notice, Gamble wrote, that the human qualities more commonly associated with women – cooperation, nurture, protectiveness, egalitarianism and altruism – must have played a vital role in human progress. In evolutionary terms, drawing assumptions about women’s abilities from the way they happened to be treated by society at that moment was narrow-minded and dangerous. Women had been systematically suppressed over the course of human history by men and their power structures, Gamble argued. They weren’t naturally inferior; they just seemed that way because they hadn’t been allowed the chance to develop their talents.

Gamble also wrote that Darwin hadn’t taken into account the existence of powerful women in some tribal societies, which might suggest that the present supremacy of men now was not how it had always been. The ancient Hindu text the Mahabharata, which she picked out as an example, speaks of women being unconfined and independent before marriage was invented. So she couldn’t help but wonder, if ‘the law of equal transmission’ applied to men as well as women, might it not be possible that males had been dragged along by the superior females of the species?

‘When a man and woman are put into competition,’ she argued, ‘both possessed of every mental quality in equal perfection, save that one has higher energy, more patience and a somewhat greater degree of physical courage, while the other has superior powers of intuition, finer and more rapid perceptions and a greater degree of endurance … the chances of the latter for gaining the ascendancy will doubtless be equal to those of the former.’

Eliza Burt Gamble’s message, like that of other scientific suffragists, proved popular. Their provocative implication was that women had been cheated out of the lives they deserved, that equality was in fact their biological right. ‘It seemed clear to me that the history of the life on the earth presents an unbroken chain of evidence going to prove the importance of the female,’ Gamble wrote in the preface to the revised edition of The Evolution of Woman, which came out in 1916.

But her army of readers, and the support of fellow activists, couldn’t win biologists around to her point of view. Her arguments were doomed never to fully enter the scientific mainstream, only to circulate outside it.

But she never gave up. She marched on in her campaign for women’s rights, and continued writing for the press. Fortunately, she lived just long enough to see her own work, as well as that of the wider movement, gain real strength. In 1893 New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant women the vote. The battle would take until 1918 in Britain, although even then the franchise was extended only to women over the age of thirty. And when Gamble died in Detroit in 1920, it was just a month after the United States ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibited citizens from being denied the right to vote because of their sex.

While the political battle was – eventually – successful, the war to change people’s minds was taking even longer. ‘Gamble’s ideas were praised in reform magazines and her writing style was generally praised, but the scientific and mainstream press balked at her conclusions and at her pretensions to write about “science”,’ says Kimberly Hamlin. The Evolution of Woman was quite widely reviewed in newspapers and academic journals, but it scarcely left a dent on science.

A scathing review of Sex Antagonism, the latest work of the respected British biologist Walter Heape, in the American Journal of Sociology in 1915 reveals just how desperately some scientists clung to their prejudices, even when society around them was changing. ‘It must have been a sense of humor which led the publishers to put this volume in their “Science Series”,’ wrote the Texas University sociologist and liberal thinker Albert Wolfe. Heape had taken his considerable scientific knowledge of reproductive biology and applied it somewhat less objectively to society, arguing that equality between the sexes was impossible because men and women were built for different roles.

Many biologists at the time agreed with Heape, including the co-author of The Evolution of Sex, John Arthur Thomson, who gave the book a positive review. But Albert Wolfe saw the danger in scientists overstepping their expertise. ‘It is a fine illustration of the sort of mental pathology a scientist, especially a biologist, can exhibit when, with slight acquaintance with other fields than his own, he ventures to dictate from “natural law” (with which Mr Heape claims to be in most intimate acquaintance) what social and ethical relation shall be,’ he mocked in his review. ‘He sees only disaster and perversion in the modern woman movement.’

Parts of science remained doggedly slow to change. Evolutionary theory progressed pretty much as before, learning few lessons from critics like Albert Wolfe, Caroline Kennard and Eliza Burt Gamble. It’s hard to picture the directions in which science might have gone if, in those important days when Charles Darwin was developing his theories of evolution, society hadn’t been quite as sexist as it was. We can only imagine how different our understanding of women might be now if Gamble had been taken a little more seriously. Historians today have regretfully described her radical perspective as the road not taken.

In the century after Gamble’s death, researchers became only more obsessed by sex differences, and by how they might pick them out, measure and catalogue them, enforcing the dogma that men are somehow better than women.

‘… finding gold in the urine of pregnant mares.’

It’s perhaps appropriate that one of the next breakthroughs in the science of sex differences came courtesy of a castrated cock.

In the 1920s a fresh string of discoveries in Europe would alter the way science understood the differences between women and men just as much as Charles Darwin and evolutionary theory had. They were foreshadowed by a strange experiment in 1849, carried out by a German medical professor, Arnold Adolph Berthold. He had been studying castrated cockerels, commonly known as capons. The removal of their testes left these birds with deliciously tender meat, which made them a popular delicacy. Aside from their meat, live capons looked different from normal cocks. They were more docile. They could also be spotted by a smaller than usual comb on top of their heads and particularly droopy red wattles underneath their jaws.

The question for Berthold was: why?