По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

I Am A Woman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

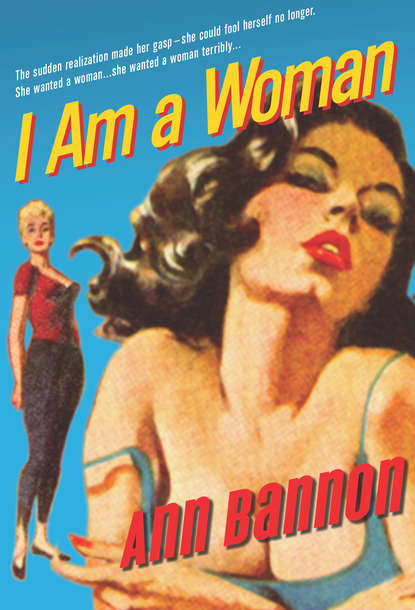

I Am A Woman

Ann Bannon

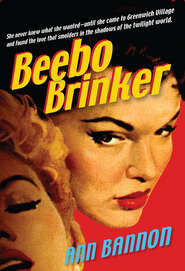

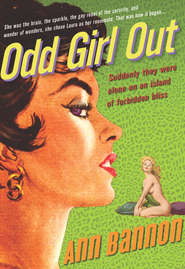

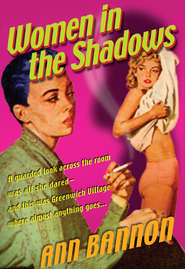

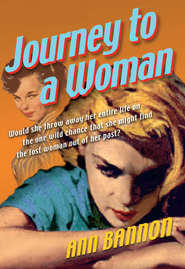

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerThe sudden realization made her gasp—she could fool herself no longer. She wanted a woman…she wanted a woman terribly…Revered as the “Queen of Lesbian Pulp” for her landmark novels of the 1950s, Ann Bannon defined lesbian fiction for the pre-Stonewall generation. I Am a Woman finds sorority sister Laura Landon leaving college heartbreak behind and embracing Greenwich Village’s lesbian bohemia. This edition includes a new introduction by the author.

I Am a Woman

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u48c28d07-c367-5b7d-b577-de755def7a21)

Title Page (#u710aae35-9575-52b9-8c75-4eb97d04d8be)

Introduction (#u796cb957-aef9-585f-b4de-4a45b2e0aaab)

Chapter One (#u533801f2-4c15-5682-acd1-fa042d59e8fa)

Chapter Two (#ud1df1c00-3f5d-5aac-be5c-d8b3b63c9810)

Chapter Three (#ubaa28533-923a-5997-83b2-fb039d9ec1b3)

Chapter Four (#u1c7c9836-6815-5320-8679-5809d4ef4219)

Chapter Five (#u8f3a7357-1fd1-5bd4-97b1-491c00f195f1)

Chapter Six (#uebcd2c88-c6b6-57ee-99c1-14ae787d4a5c)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_384195e4-d86c-51e3-89e7-bd46deb30703)

Many years ago, when this book was in its final creative stages, I had a lucky invitation to come to New York and finish it in the home of friends of friends. They were young career women, living in a very small apartment in a very old building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, near Columbia University. Luckier still, they were on the top floor, and in the hallway outside their front door stood a dubious flight of stairs that took one to the roof. There I repaired when I got stuck, or the typewriter fought back, or the coffee ran out, and gazed out at marvelous Manhattan. I especially liked going up there after dark, when the great city was spread out like a carpet of sparklers, brilliant with promise. I had just invented Beebo Brinker for this book, and with the intensity of youth, I imagined her real-life counterpart out there somewhere, down in the Village going about her business, while I, on my roof, was trying to capture her story. I spent a fair amount of time leaning on the crumbly old parapets, staring deep into the lights and wondering if there were a real Beebo on this planet. If there were, would I ever meet her? Would she be like the woman I had contrived out of sheer need so she would at least exist somewhere in the world, even if only in the pages of my book? Was there anybody like her anywhere? Big, bold, handsome, the quintessential 1950s buccaneer butch, she was a heller and I adored her.

Not once did it occur to me to wonder if other people would ever know or care about Beebo Brinker. Not once did I ask myself if other women would fall under her spell, if readers would be amused and engaged by her, if she would develop a life of her own that would carry her across the decades until I would find myself sharing her with the rest of the world. What I wanted to know was, Would she be there for me, more real than reality? Would she rescue me from the frustration and isolation of a difficult marriage, from the impatience to be my own person before circumstances made it possible, from all the personal needs deferred in the interests of cherishing my children and finding my way in this life? It was a lot to dump on a fictional character. But she was my creature, my fantasy—and once conceived, she stood up and, with her broad shoulders, helped me lift my burdens.

Up there on that long-ago rooftop, I didn’t foresee Beebo’s future, but I did try to glimpse my own. Looking out at all those bright electric blooms spread at my feet, I pondered, If each one were a reader, how many would remember the name of Ann Bannon? Would I ever come back to Manhattan some day to acclaim? Reluctantly I acknowledged the realities: I was writing paperback pulp fiction. The Beatles had yet to glamorize the “Paperback Writer.” The stories were ephemeral; even the physical material of the books was so fragile that it hardly survived a single reading. The glue dried and cracked, the pages fell out, the paper yellowed after mere months, and the ink ate right through it anyway. The covers shouted “Sleaze!” The critics ignored the books in droves, and “serious” writers were going to the hardback publishers. Of course, we did have readers. People were grabbing the pulps off drugstore shelves and bus station kiosks, and reading them almost in a gulp. But then they tossed them in trash cans and forgot them. Given this precarious bit of fleeting notoriety, I had not yet even mustered the courage to acknowledge my authorship to friends and family, much less to the public. No, there was no immortality here for Ann Bannon.

So I worked on I Am a Woman under no illusions about the prospects for enduring fame. That I am sitting down to share this with my readers forty-five years and five editions later is a true astonishment. But the perdurable appeal of the butch-femme dichotomy is not. It has, however, undergone some interesting changes.

When I was writing I Am a Woman, the unquestioned role choices open to lesbians were two: butch or femme. As Robin Tyler has observed, even if you weren’t sure which one you were, you wanted to be butch, because they didn’t have to do the dishes. Well, maybe it wasn’t that simple for everyone, but women generally were not nearly as experimental with those roles as they later became. Butches were strong, tough, heroic, romantic. They fought battles in back alleys over femmes and were quite capable of ruling the roost. The femmes, by contrast, could be more girly; some were, in a way, early examples of “lipstick lesbians.” They might appear seductive, compliant, even pretty. It was almost a mirror image of mainstream society: the guy-gals and the gal-gals. It was exciting, sexy, and dramatic. But it was also confining, and as the Women’s Movement unfolded in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it began to seem rigid and outdated. This was no way to run a romantic partnership, with one member always on top, one always on the bottom.

As so often happens when the pendulum swings, it swings the old ways right out of the ballpark. The butch-femme dichotomy was rejected altogether for a while, replaced with more egalitarian liaisons. But it always exerted a tug on the heart, propelled by the sheer charisma of the archetypal bulldyke: independent, sensual, provocative, and more than a little dangerous. Today, among young women, it seems to have a place again, as long as it is recognized as a choice. But when Laura met Beebo in that lesbian bar called The Cellar all those years ago, both women were already locked into the paradigm. Laura was feminine in the traditional way. Her defenses, her fear of emotional entanglement, quickly melted under the laser of Beebo’s sexual focus. And on her side, Beebo was intrigued by Laura’s beguiling femaleness.

I knew of no other way to write about them. Interestingly, I had tried other things. After Odd Girl Out, my first book, was published, I completed about a hundred pages of what was to be the second book for Fawcett Publications. They were the publishers of the Gold Medal Series, under whose imprint all my books were originally published. The editor, Dick Carroll, saw those pages and hated them. I was trying to “go straight,” thinking it would be easier to face friends and family as an author with at least one conventional romance under my writer’s belt. But Dick discerned at once that, whatever the merits of the plot, I didn’t even like my characters; it was not possible to care how their lives turned out. They did not, as good characters must, talk to me at all.

Once again, he told me what he had told me at the beginning, when I was trying to bring Odd Girl Out to life: “Go back to the people you love and breathe some life into them.” Thus was born the idea of developing a series and making some of the characters ongoing. I had left Beth behind in the first book to marry the college man who loved her. But I had put Laura on the train out of her college town with vague aspirations for a new life somewhere where she could be who she really was. After a blow-up with her difficult father, Merrill Landon, she decamped for New York. But whom would she meet there and what would she do?

I had been reading everything I could get my hands on in the two years or so between Odd Girl Out and I Am a Woman, trying to encompass the whole wonderful, alarming, irresistible idea of women together. I had learned the word lesbian. I had learned about butches and femmes. In travel books, I had discovered that mythical hamlet, Manhattan’s own Brigadoon, Greenwich Village. I was thoroughly enchanted. But something was missing: I had Laura, my heroine, but I was lacking a hero. The idea of one had been forming out of the mists in my mind during those two years. But it would take the perfect name to bring her to life.

Before that could happen, I had to do some “field work” and get to know my chosen territory. Living first in Philadelphia, where it was easy to get to New York, and later in Southern California, where it was not, I nevertheless made my authorial pilgrimages to Greenwich Village. With the help of friends, most notably Marijane Meaker and Sandra Scoppetone, wonderful writers themselves, I went exploring and found the haunts of Beebo Brinker: the little brownstones, the specialty shops, the crooked streets, and the wonderful, slightly trashy, and wholly mesmerizing women’s bars, replete with their full complement of admiring “johns,” tucked into the nooks of the Village.

By the time the Naiad editions were settling into middle age, somewhere in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I began to realize how many women had taken Beebo and Laura to their hearts. In the most unexpected places, I found references to them: in a poem by Joan Nestle, an essay of Kate Millett’s, Audre Lorde’s autobiography; in the wrenching life story of Cheryl Crane, Lana Turner’s daughter; in college courses, master’s theses, articles both scholarly and popular; and ultimately, in communications from women and even some men readers from many parts of the globe. It leaves me wondering what sort of stories I would have produced in the ‘50s and ‘60s, had I known then that my work, seemingly so safe from formal scrutiny, would be discussed and analyzed by future generations. The writing might have been better, but it certainly would have been more guarded and self-conscious.

The same critical scorn that deemed the work of us paperback writers unworthy of attention had also seemed to guarantee us privacy, the chance to explore and experiment, to say the unsayable, and to fade away peacefully from the publishing scene when the paperbacks finished their popular run. But some of us didn’t fade. After all these years, it is a rare blessing to have the public’s attention and support, but a mixed blessing all the same, just because of the disconcerting attention. There are times when I wish I had done enough living back then, when I was doing so much writing, to justify my grand generalizations, my cocksure assertions, my pronouncements on life and love. I was awfully damn young. But maybe it’s just as well that I didn’t have the advantage of maturity to temper Beebo’s outbursts and Laura’s emotional extremes. After all, that’s how it feels and goes down when you’re young.

So here are Beebo and Laura meeting for the first time. Where did the characters come from? The idea for Laura was based on my friendship with a sorority sister during my undergraduate days. She was two years younger than I and had many of the personality traits that make Laura both lovable and exasperating: shyness, lack of self-confidence, and hypersensitivity, but also warmth, sweetness of character, and, once she trusted you, a staunch friendship. She was slightly taller than average, with bright Scandinavian blonde hair and an engaging smile. After we got to be friends, she confided in me about her troubles with her tough-minded and abrupt father, who sounded to me like a man insensitive in reverse proportion to his daughter’s delicacy of feeling. The days when his letters arrived were downers for her, and they gave me a sort of scaffolding on which to embroider stories about her interior life. I recognized in “Laura” some of my own shaky sense of self. But unlike me, she rarely dated, seeming content to stay home most weekends and to shine academically. Whether or not she felt stirrings of romantic affection for women, I will never know, although I have my sympathetic suspicions. But I remember her as a sweetheart, with a shy warmth, and a prettiness and appeal she didn’t recognize in herself.

Beebo was another story. She was my own unrealized romantic phantom. There was another college friend, it is only fair to concede, who gave me the physical prototype. She was taller than the rest of us and strikingly handsome, with a crop of wavy, dark-blonde hair and an irresistible smile. Her nickname was one of those too-cute tomboy variations on a boy’s name. She hated it and made us promise never to use it, but her formal name didn’t seem to suit her. I remember running into her in the dorm bathroom—one of those gray marble affairs with rows of icy washbowls and green toilet stalls—in her skivvies, and trying not to admire her unduly. I think I made her a little squirmy, and she did seem to be in love with her serious beau, whom she married upon graduation. Well, we win a few and lose a few.

Actually, I didn’t quite know in that early period in my life which glamorous options to hang on the bare architecture of my fantasy hero. I just thought she needed to look like “Tommie” and to have the “heart and stomach of a king,” to quote Elizabeth I. It took me a few trips to Greenwich Village, and the reading of some of the then-current pulp paperbacks, to begin to recognize the qualities she required and to flesh them out. By that time, I was into the planning for this book and ruminating hard about my characters.

And so we come back to the roof of that Upper West Side apartment, looking down on the lights of the city. One night, staring across the twinkling horizon and seeing the character in my mind’s eye, I thought for the thousandth time, “If I could just find a name for her, she would come into focus for me.” For whatever blessed reason, it was at that moment that the childhood nickname of an old friend floated back into my mind: Beebo. I seized upon it and captured my Beebo whole, intact, entire. Never again was I the same, once Beebo began to breathe. The Beebo Brinker Chronicles were off and running, and so was their author. Thus it was that Beebo met Laura, and they began their passionate but rocky odyssey.

There is one other character whose genesis deserves attention for a moment. He is Jack Mann, that cynical, witty, sometimes prickly, but quite lovable gay man who makes his initial bow in this novel. He is shamelessly plucked, right down to his hair and fingernails, from an old hometown friend whom I met through my first serious beau—a “Jack,” too, but with a different last name. The original Jack, probably five or six years older than I, loved traditional jazz, and in my family, it was played a lot. My stepfather was a superb jazz piano player, and my mother, a one-woman cheering section. The rest of us were young, feisty, and crazy about the music, which was undergoing a revival of interest in the ‘40s and ‘50s. We worshiped Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Sidney Bechet, Muggsy Spanier, and many less well known but excellent musicians playing in the genre. A lot of them came through the Chicago area, where we lived, and our informal weekend jam sessions became well enough recognized to draw some of them out to our suburban bungalow on an occasional Saturday night. We hosted Lil Hardin Armstrong (Louis’s first wife and a great jazz pianist herself), Johnny and Baby Dodds (clarinet and drum players par excellence), and others. Jack just gobbled it up. He would settle into an old easy chair in the living room, legs propped up on a hassock and cigarette in mouth, and drum with his fingers on the chair arms. I can’t count the beers that disappeared on such an evening, but there are ancient tapes of the music, and it was nothing to apologize for.

The original Jack was always a treat to have in our company. My little brothers adored him, but they didn’t learn his name on the first visit. There were so many young musicians around on weekends that we had a standing joke that they were all uncles: Uncle Bob, Uncle Bill, Uncle Harry. So Jack, on his first visit, was greeted with, “Here comes Uncle Somebody.” It stuck, even after they mastered his name. He had a funny take on life—ironic, droll, and rather unsparing—and he would sit in that chair and shoot zingers at us between musical numbers. We all loved him. I noticed, however, that unlike the other young men who dropped by so often, he never brought a date with him. Whether or not he was gay is another of those mysteries I never cracked.

I began to lose track of Jack only after I went away to college, when I was able to get news about him only occasionally from the hometown boy I was dating. Finally, shortly after my college graduation, I thought to ask the now-former beau, “Where is Jack these days?” The answer was not reassuring. He had gone to work for the CIA and had been sent to Ho Chi Minh City, then known as Saigon. He had, in fact, made several trips there, and finally, he did not come back from one of those trips. By now, it was the early 1960s, an increasingly dangerous time to be in Southeast Asia. No one from those heedless, happy times in my hometown seems to know how his story ended. It is a source of sorrow to me that he drifted out of my life without leaving a trace—except, I venture to hope, in his incarnation in these stories as Jack Mann, the good-hearted, perpetually frustrated gay man who could never resist taking in lost kids and helping them find jobs and make their way in the Big City. Alas, they always made their way to some other lover and left Jack in the lurch. But he never lost hope, nor do I, that someday, somehow, “Uncle Somebody” will come strolling up the front walk, cracking wise and charming us all.

And oh, the drinking! And oh, the smoking! You follow it all in the narrative, and you really wonder how any of us survived those days. And the truth is, there were casualties. But consider the reason. Where else were we to go? What women’s bookstores, what culture clubs, what social safety nets were there for women then? How did they even find one another? They resorted to the one social institution that represented a haven, a place to meet old friends and find new ones, a place to relax and be oneself—a place, in other words, that served an indispensable function in a perilous era. That some of the women from the ‘50s and ‘60s were sacrificed to the flow of liquor and smoke, lamentable though it is, is hardly to be wondered at. The options were so few and the need was so great that the bars were always crowded. Still, those women must be remembered with affection and gratitude; they were pioneers, too, and helped to build the foundation of sisterhood we all stand on today.

Last, the title. I had wanted to call the novel Strangers in This World. But Dick Carroll wouldn’t go for it. I suspect he knew much better than I that my title would not work as a code phrase to alert potential readers to its lesbian content. He was a canny marketer and used every available strategy to promote the books. Indeed, he had come up with the rather clever Odd Girl Out as the title for my first book. So what did he invent for this one? I Am a Woman. I always thought it was a vacuous sort of name for a book. It has no real referent: Who, for example, is the “I”? The book is not a first-person narrative. The title makes sense only as part of a longer sentence followed by a question, which had to be reproduced in its entirety on the cover of the original edition: I Am a Woman in Love with a Woman. Must Society Reject Me? What a mouthful of angst. I thought it was unwieldy and irrelevant to the story line; it could have been slapped on virtually any lesbian pulp paperback. It had no special connection to this one. But I Am a Woman the book became and remains. And in that incarnation, it sold like the proverbial hotcakes in 1959. So Dick Carroll was right and I was wrong. It still seems unappealing to me, an almost nameless name. On the other hand, this book, vague title and all, is one of my favorites in the series.

Ann Bannon

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerThe sudden realization made her gasp—she could fool herself no longer. She wanted a woman…she wanted a woman terribly…Revered as the “Queen of Lesbian Pulp” for her landmark novels of the 1950s, Ann Bannon defined lesbian fiction for the pre-Stonewall generation. I Am a Woman finds sorority sister Laura Landon leaving college heartbreak behind and embracing Greenwich Village’s lesbian bohemia. This edition includes a new introduction by the author.

I Am a Woman

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u48c28d07-c367-5b7d-b577-de755def7a21)

Title Page (#u710aae35-9575-52b9-8c75-4eb97d04d8be)

Introduction (#u796cb957-aef9-585f-b4de-4a45b2e0aaab)

Chapter One (#u533801f2-4c15-5682-acd1-fa042d59e8fa)

Chapter Two (#ud1df1c00-3f5d-5aac-be5c-d8b3b63c9810)

Chapter Three (#ubaa28533-923a-5997-83b2-fb039d9ec1b3)

Chapter Four (#u1c7c9836-6815-5320-8679-5809d4ef4219)

Chapter Five (#u8f3a7357-1fd1-5bd4-97b1-491c00f195f1)

Chapter Six (#uebcd2c88-c6b6-57ee-99c1-14ae787d4a5c)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_384195e4-d86c-51e3-89e7-bd46deb30703)

Many years ago, when this book was in its final creative stages, I had a lucky invitation to come to New York and finish it in the home of friends of friends. They were young career women, living in a very small apartment in a very old building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, near Columbia University. Luckier still, they were on the top floor, and in the hallway outside their front door stood a dubious flight of stairs that took one to the roof. There I repaired when I got stuck, or the typewriter fought back, or the coffee ran out, and gazed out at marvelous Manhattan. I especially liked going up there after dark, when the great city was spread out like a carpet of sparklers, brilliant with promise. I had just invented Beebo Brinker for this book, and with the intensity of youth, I imagined her real-life counterpart out there somewhere, down in the Village going about her business, while I, on my roof, was trying to capture her story. I spent a fair amount of time leaning on the crumbly old parapets, staring deep into the lights and wondering if there were a real Beebo on this planet. If there were, would I ever meet her? Would she be like the woman I had contrived out of sheer need so she would at least exist somewhere in the world, even if only in the pages of my book? Was there anybody like her anywhere? Big, bold, handsome, the quintessential 1950s buccaneer butch, she was a heller and I adored her.

Not once did it occur to me to wonder if other people would ever know or care about Beebo Brinker. Not once did I ask myself if other women would fall under her spell, if readers would be amused and engaged by her, if she would develop a life of her own that would carry her across the decades until I would find myself sharing her with the rest of the world. What I wanted to know was, Would she be there for me, more real than reality? Would she rescue me from the frustration and isolation of a difficult marriage, from the impatience to be my own person before circumstances made it possible, from all the personal needs deferred in the interests of cherishing my children and finding my way in this life? It was a lot to dump on a fictional character. But she was my creature, my fantasy—and once conceived, she stood up and, with her broad shoulders, helped me lift my burdens.

Up there on that long-ago rooftop, I didn’t foresee Beebo’s future, but I did try to glimpse my own. Looking out at all those bright electric blooms spread at my feet, I pondered, If each one were a reader, how many would remember the name of Ann Bannon? Would I ever come back to Manhattan some day to acclaim? Reluctantly I acknowledged the realities: I was writing paperback pulp fiction. The Beatles had yet to glamorize the “Paperback Writer.” The stories were ephemeral; even the physical material of the books was so fragile that it hardly survived a single reading. The glue dried and cracked, the pages fell out, the paper yellowed after mere months, and the ink ate right through it anyway. The covers shouted “Sleaze!” The critics ignored the books in droves, and “serious” writers were going to the hardback publishers. Of course, we did have readers. People were grabbing the pulps off drugstore shelves and bus station kiosks, and reading them almost in a gulp. But then they tossed them in trash cans and forgot them. Given this precarious bit of fleeting notoriety, I had not yet even mustered the courage to acknowledge my authorship to friends and family, much less to the public. No, there was no immortality here for Ann Bannon.

So I worked on I Am a Woman under no illusions about the prospects for enduring fame. That I am sitting down to share this with my readers forty-five years and five editions later is a true astonishment. But the perdurable appeal of the butch-femme dichotomy is not. It has, however, undergone some interesting changes.

When I was writing I Am a Woman, the unquestioned role choices open to lesbians were two: butch or femme. As Robin Tyler has observed, even if you weren’t sure which one you were, you wanted to be butch, because they didn’t have to do the dishes. Well, maybe it wasn’t that simple for everyone, but women generally were not nearly as experimental with those roles as they later became. Butches were strong, tough, heroic, romantic. They fought battles in back alleys over femmes and were quite capable of ruling the roost. The femmes, by contrast, could be more girly; some were, in a way, early examples of “lipstick lesbians.” They might appear seductive, compliant, even pretty. It was almost a mirror image of mainstream society: the guy-gals and the gal-gals. It was exciting, sexy, and dramatic. But it was also confining, and as the Women’s Movement unfolded in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it began to seem rigid and outdated. This was no way to run a romantic partnership, with one member always on top, one always on the bottom.

As so often happens when the pendulum swings, it swings the old ways right out of the ballpark. The butch-femme dichotomy was rejected altogether for a while, replaced with more egalitarian liaisons. But it always exerted a tug on the heart, propelled by the sheer charisma of the archetypal bulldyke: independent, sensual, provocative, and more than a little dangerous. Today, among young women, it seems to have a place again, as long as it is recognized as a choice. But when Laura met Beebo in that lesbian bar called The Cellar all those years ago, both women were already locked into the paradigm. Laura was feminine in the traditional way. Her defenses, her fear of emotional entanglement, quickly melted under the laser of Beebo’s sexual focus. And on her side, Beebo was intrigued by Laura’s beguiling femaleness.

I knew of no other way to write about them. Interestingly, I had tried other things. After Odd Girl Out, my first book, was published, I completed about a hundred pages of what was to be the second book for Fawcett Publications. They were the publishers of the Gold Medal Series, under whose imprint all my books were originally published. The editor, Dick Carroll, saw those pages and hated them. I was trying to “go straight,” thinking it would be easier to face friends and family as an author with at least one conventional romance under my writer’s belt. But Dick discerned at once that, whatever the merits of the plot, I didn’t even like my characters; it was not possible to care how their lives turned out. They did not, as good characters must, talk to me at all.

Once again, he told me what he had told me at the beginning, when I was trying to bring Odd Girl Out to life: “Go back to the people you love and breathe some life into them.” Thus was born the idea of developing a series and making some of the characters ongoing. I had left Beth behind in the first book to marry the college man who loved her. But I had put Laura on the train out of her college town with vague aspirations for a new life somewhere where she could be who she really was. After a blow-up with her difficult father, Merrill Landon, she decamped for New York. But whom would she meet there and what would she do?

I had been reading everything I could get my hands on in the two years or so between Odd Girl Out and I Am a Woman, trying to encompass the whole wonderful, alarming, irresistible idea of women together. I had learned the word lesbian. I had learned about butches and femmes. In travel books, I had discovered that mythical hamlet, Manhattan’s own Brigadoon, Greenwich Village. I was thoroughly enchanted. But something was missing: I had Laura, my heroine, but I was lacking a hero. The idea of one had been forming out of the mists in my mind during those two years. But it would take the perfect name to bring her to life.

Before that could happen, I had to do some “field work” and get to know my chosen territory. Living first in Philadelphia, where it was easy to get to New York, and later in Southern California, where it was not, I nevertheless made my authorial pilgrimages to Greenwich Village. With the help of friends, most notably Marijane Meaker and Sandra Scoppetone, wonderful writers themselves, I went exploring and found the haunts of Beebo Brinker: the little brownstones, the specialty shops, the crooked streets, and the wonderful, slightly trashy, and wholly mesmerizing women’s bars, replete with their full complement of admiring “johns,” tucked into the nooks of the Village.

By the time the Naiad editions were settling into middle age, somewhere in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I began to realize how many women had taken Beebo and Laura to their hearts. In the most unexpected places, I found references to them: in a poem by Joan Nestle, an essay of Kate Millett’s, Audre Lorde’s autobiography; in the wrenching life story of Cheryl Crane, Lana Turner’s daughter; in college courses, master’s theses, articles both scholarly and popular; and ultimately, in communications from women and even some men readers from many parts of the globe. It leaves me wondering what sort of stories I would have produced in the ‘50s and ‘60s, had I known then that my work, seemingly so safe from formal scrutiny, would be discussed and analyzed by future generations. The writing might have been better, but it certainly would have been more guarded and self-conscious.

The same critical scorn that deemed the work of us paperback writers unworthy of attention had also seemed to guarantee us privacy, the chance to explore and experiment, to say the unsayable, and to fade away peacefully from the publishing scene when the paperbacks finished their popular run. But some of us didn’t fade. After all these years, it is a rare blessing to have the public’s attention and support, but a mixed blessing all the same, just because of the disconcerting attention. There are times when I wish I had done enough living back then, when I was doing so much writing, to justify my grand generalizations, my cocksure assertions, my pronouncements on life and love. I was awfully damn young. But maybe it’s just as well that I didn’t have the advantage of maturity to temper Beebo’s outbursts and Laura’s emotional extremes. After all, that’s how it feels and goes down when you’re young.

So here are Beebo and Laura meeting for the first time. Where did the characters come from? The idea for Laura was based on my friendship with a sorority sister during my undergraduate days. She was two years younger than I and had many of the personality traits that make Laura both lovable and exasperating: shyness, lack of self-confidence, and hypersensitivity, but also warmth, sweetness of character, and, once she trusted you, a staunch friendship. She was slightly taller than average, with bright Scandinavian blonde hair and an engaging smile. After we got to be friends, she confided in me about her troubles with her tough-minded and abrupt father, who sounded to me like a man insensitive in reverse proportion to his daughter’s delicacy of feeling. The days when his letters arrived were downers for her, and they gave me a sort of scaffolding on which to embroider stories about her interior life. I recognized in “Laura” some of my own shaky sense of self. But unlike me, she rarely dated, seeming content to stay home most weekends and to shine academically. Whether or not she felt stirrings of romantic affection for women, I will never know, although I have my sympathetic suspicions. But I remember her as a sweetheart, with a shy warmth, and a prettiness and appeal she didn’t recognize in herself.

Beebo was another story. She was my own unrealized romantic phantom. There was another college friend, it is only fair to concede, who gave me the physical prototype. She was taller than the rest of us and strikingly handsome, with a crop of wavy, dark-blonde hair and an irresistible smile. Her nickname was one of those too-cute tomboy variations on a boy’s name. She hated it and made us promise never to use it, but her formal name didn’t seem to suit her. I remember running into her in the dorm bathroom—one of those gray marble affairs with rows of icy washbowls and green toilet stalls—in her skivvies, and trying not to admire her unduly. I think I made her a little squirmy, and she did seem to be in love with her serious beau, whom she married upon graduation. Well, we win a few and lose a few.

Actually, I didn’t quite know in that early period in my life which glamorous options to hang on the bare architecture of my fantasy hero. I just thought she needed to look like “Tommie” and to have the “heart and stomach of a king,” to quote Elizabeth I. It took me a few trips to Greenwich Village, and the reading of some of the then-current pulp paperbacks, to begin to recognize the qualities she required and to flesh them out. By that time, I was into the planning for this book and ruminating hard about my characters.

And so we come back to the roof of that Upper West Side apartment, looking down on the lights of the city. One night, staring across the twinkling horizon and seeing the character in my mind’s eye, I thought for the thousandth time, “If I could just find a name for her, she would come into focus for me.” For whatever blessed reason, it was at that moment that the childhood nickname of an old friend floated back into my mind: Beebo. I seized upon it and captured my Beebo whole, intact, entire. Never again was I the same, once Beebo began to breathe. The Beebo Brinker Chronicles were off and running, and so was their author. Thus it was that Beebo met Laura, and they began their passionate but rocky odyssey.

There is one other character whose genesis deserves attention for a moment. He is Jack Mann, that cynical, witty, sometimes prickly, but quite lovable gay man who makes his initial bow in this novel. He is shamelessly plucked, right down to his hair and fingernails, from an old hometown friend whom I met through my first serious beau—a “Jack,” too, but with a different last name. The original Jack, probably five or six years older than I, loved traditional jazz, and in my family, it was played a lot. My stepfather was a superb jazz piano player, and my mother, a one-woman cheering section. The rest of us were young, feisty, and crazy about the music, which was undergoing a revival of interest in the ‘40s and ‘50s. We worshiped Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Sidney Bechet, Muggsy Spanier, and many less well known but excellent musicians playing in the genre. A lot of them came through the Chicago area, where we lived, and our informal weekend jam sessions became well enough recognized to draw some of them out to our suburban bungalow on an occasional Saturday night. We hosted Lil Hardin Armstrong (Louis’s first wife and a great jazz pianist herself), Johnny and Baby Dodds (clarinet and drum players par excellence), and others. Jack just gobbled it up. He would settle into an old easy chair in the living room, legs propped up on a hassock and cigarette in mouth, and drum with his fingers on the chair arms. I can’t count the beers that disappeared on such an evening, but there are ancient tapes of the music, and it was nothing to apologize for.

The original Jack was always a treat to have in our company. My little brothers adored him, but they didn’t learn his name on the first visit. There were so many young musicians around on weekends that we had a standing joke that they were all uncles: Uncle Bob, Uncle Bill, Uncle Harry. So Jack, on his first visit, was greeted with, “Here comes Uncle Somebody.” It stuck, even after they mastered his name. He had a funny take on life—ironic, droll, and rather unsparing—and he would sit in that chair and shoot zingers at us between musical numbers. We all loved him. I noticed, however, that unlike the other young men who dropped by so often, he never brought a date with him. Whether or not he was gay is another of those mysteries I never cracked.

I began to lose track of Jack only after I went away to college, when I was able to get news about him only occasionally from the hometown boy I was dating. Finally, shortly after my college graduation, I thought to ask the now-former beau, “Where is Jack these days?” The answer was not reassuring. He had gone to work for the CIA and had been sent to Ho Chi Minh City, then known as Saigon. He had, in fact, made several trips there, and finally, he did not come back from one of those trips. By now, it was the early 1960s, an increasingly dangerous time to be in Southeast Asia. No one from those heedless, happy times in my hometown seems to know how his story ended. It is a source of sorrow to me that he drifted out of my life without leaving a trace—except, I venture to hope, in his incarnation in these stories as Jack Mann, the good-hearted, perpetually frustrated gay man who could never resist taking in lost kids and helping them find jobs and make their way in the Big City. Alas, they always made their way to some other lover and left Jack in the lurch. But he never lost hope, nor do I, that someday, somehow, “Uncle Somebody” will come strolling up the front walk, cracking wise and charming us all.

And oh, the drinking! And oh, the smoking! You follow it all in the narrative, and you really wonder how any of us survived those days. And the truth is, there were casualties. But consider the reason. Where else were we to go? What women’s bookstores, what culture clubs, what social safety nets were there for women then? How did they even find one another? They resorted to the one social institution that represented a haven, a place to meet old friends and find new ones, a place to relax and be oneself—a place, in other words, that served an indispensable function in a perilous era. That some of the women from the ‘50s and ‘60s were sacrificed to the flow of liquor and smoke, lamentable though it is, is hardly to be wondered at. The options were so few and the need was so great that the bars were always crowded. Still, those women must be remembered with affection and gratitude; they were pioneers, too, and helped to build the foundation of sisterhood we all stand on today.

Last, the title. I had wanted to call the novel Strangers in This World. But Dick Carroll wouldn’t go for it. I suspect he knew much better than I that my title would not work as a code phrase to alert potential readers to its lesbian content. He was a canny marketer and used every available strategy to promote the books. Indeed, he had come up with the rather clever Odd Girl Out as the title for my first book. So what did he invent for this one? I Am a Woman. I always thought it was a vacuous sort of name for a book. It has no real referent: Who, for example, is the “I”? The book is not a first-person narrative. The title makes sense only as part of a longer sentence followed by a question, which had to be reproduced in its entirety on the cover of the original edition: I Am a Woman in Love with a Woman. Must Society Reject Me? What a mouthful of angst. I thought it was unwieldy and irrelevant to the story line; it could have been slapped on virtually any lesbian pulp paperback. It had no special connection to this one. But I Am a Woman the book became and remains. And in that incarnation, it sold like the proverbial hotcakes in 1959. So Dick Carroll was right and I was wrong. It still seems unappealing to me, an almost nameless name. On the other hand, this book, vague title and all, is one of my favorites in the series.