По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

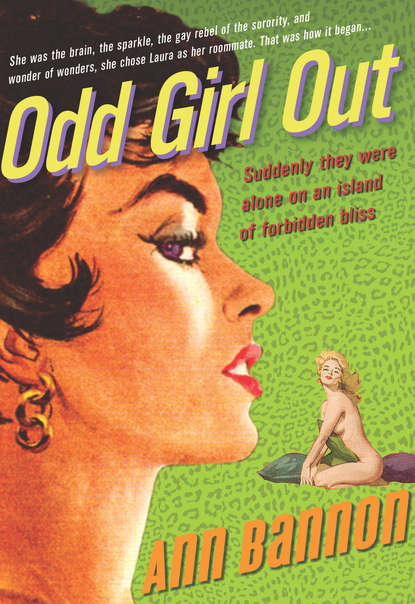

Odd Girl Out

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

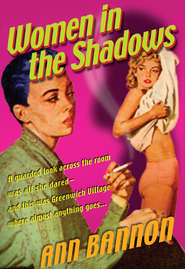

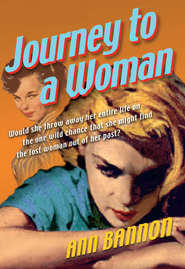

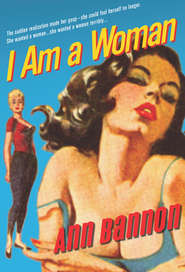

Neither were we consulted on the titles. I can remember tearing open the brown paper packages in which complimentary copies of my novels would arrive, and bracing myself for the shock of the cover art and, on occasion, even the title. The blurbs were lubriciously inventive: “The Savage Novel of a Lesbian on the Loose.” “They came to college sweet, pretty, and unsuspecting. But the house mother was strangely corrupt …” “Mary lacerated the flesh of a hundred girls with her searing caresses.” “The world of the third sex … that land of strange loves and rapacious passions.” “It was hard to figure out who was male and who was female … sometimes they were interchangeable.” “She found herself climbing down a ladder of flesh into a cesspool of Lesbian depravity.” With blurbs like these, who needed the critics’ praise to sell books? They flew off the shelves. And still nobody in the wider world took notice except the readers themselves.

Then the letters started pouring in. Those from the men were often propositions; those from the women were cries of the heart. The female readers wrote from little towns all over the country. Such was their isolation that many of them were grateful to me for reassuring them that they were not totally alone in the world. They wanted me to tell their stories, they wanted me to give them advice, and they wanted to meet me. They were sweet, tentative, grateful, scared, and even needier than I, if that’s possible, of education and support.

I wish I had those letters still—they were lost in one of many moves over the years. They would astonish the far more knowledgeable readership of women today in their ingenuousness, their yearning, their sense of exile, but with it all, their good humor, their sheer guts and perseverance. These women lived in a world where they thought themselves to be painfully unique. The bottom line was, they imagined themselves doomed to solitude in their yearnings for the rest of their lives and sadly, deservedly so, since they had no positive role models to contradict such self-prejudice. I admired and even loved them, although I only ever met one of them, through her personal determination to make it happen. I often think of them and hope their lives turned out better than they could then have known or dared to hope.

But these letters overwhelmed me. What to tell them? I was being appealed to for help as if I were a lesbian Ann Landers. Little did they know it was a case of the blind leading the blind. What could I, in my naiveté, possibly say that would help them through their sexual exile, give them warmth and hope? The only gift I could give back to these readers was another story.

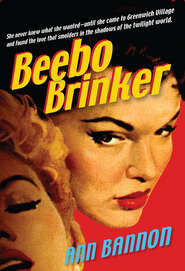

In my visits to Greenwich Village, I had already learned to recognize the butch/femme dichotomy so influential at the time, and I wanted to write a book about a big, handsome, exasperating, reckless, bright, funny, irresistible butch. She would do what I could not. She would be what I could not. I already knew her in the theater of my mind, and I even knew her name: Beebo Brinker. I stole the “Beebo” from a childhood friend who couldn’t pronounce her given name of Beverly. The “Brinker” was my own inspiration. She was never modeled on a real woman, although several were influential in various ways. Instead she sprang like Minerva from my brow, propelled to life by the twin engines of fantasy and need.

When Beebo was at her buccaneer best, I was infatuated with her myself. When she was at her destructive worst, I was using her as a dumping ground for my own frustrations. She was tough and could take it, and made my life better and my spirit stronger by shouldering the troubles I couldn’t resolve. But it resulted in giving her a dark side I now wish I could soften.

I gave at least some of the stories a happy ending, sort of. Nobody had to be shot or jump in front of a train for the sin of loving another woman. Bad things did happen that reflected the arrogant ignorance of the authorities, the contempt of conventional society, and the occasional desperation of the women of the times; modern readers may feel impatient with some of this now, but it was part of life back then. But still there was humor and there was love, in at least as good measure, and I am most proud of having captured some of that temper of the times as well.

I had no idea I was being brave or daring when I started writing, so perhaps it doesn’t count. But after Odd Girl Out was published and I realized I was, I kept on writing anyway, so perhaps it does. One of the hardest things I ever had to do was hand a copy of the first edition of Odd Girl Out to my mother to read. It’s the one that shows the author’s name as “A. Bannon.” I was too shy then even to let my first name be printed on the cover. My mother was a strikingly pretty and spirited lady, whose beauty and willfulness had gotten her into three marriages and many scrapes. But for all that, she was raised by my little Victorian grandmother, who steeped her in the manners required of nice girls. It was part of the code that a lady simply sailed past unpleasantness wherever possible, taking no note of it.

My mother read the book and I waited for the toughest review of my life. As I waited, I thought of what must be going through her mind: all those home-movie recollections of a quirky little girl with a passion for books and music, cautious with new friendships, reassuringly like her age-mates to the eye but disturbingly intense and eccentric in other ways. Still, there was nothing in her memories to prepare her for what she was reading. It must have been breathtaking. She, of course, would never say so. I think she took courage from the fact that I was then a pretty young housewife and mother. Things couldn’t be too far off track. And besides, I was her daughter; she was going to support me if she could. Finally, she put the book down and said thoughtfully, “Sweetheart … I didn’t know you had it in you.” And then, because I was hers, and I had done something difficult in writing a book and getting it published, she added, “I’m proud of you.” I started breathing again. “But,” she added, “don’t ever show this to your grandmother.” I never did.

Perhaps it is only fair to mention the husband who played so minimal a role in Ann Bannon’s existence but so great a role in mine. He was aware of the general theme of the books, but it interested him not at all. The royalty checks, however, did. I think for that reason and others of his own, he did not try to discourage me. He read no more than a few paragraphs of Odd Girl Out, and that was enough for him. He was a basically good person; he meant well and he loved me, and I will not lay all the blame for my grief in that marriage at his feet. Suffice it to say that I have never regretted its ending, and am grateful to leave it at rest in the past. My children are now beautiful and successful adults, so there was a magnificent reward for the difficult years.

Why didn’t I stay in Greenwich Village when I had the chance? Why didn’t I break out of wedlock? Well, this was 1956. I was twenty-two and while I had a college education, it was ornamental; I had no marketable skills. I was also very much my mother’s child. In our family there was a grand tradition of soldiering through in the traditional role, whatever the challenges. My mother had done it and her mother before her. They were both very much alive and I was not going to let them down. This was familiar territory; better the shackles of the known than the terrors of the new and unfathomable.

Perhaps, also, I was just plain scared to assume an identity that seemed to me full of mystery, one which I was just beginning to recognize and understand. It had been clear to me from my earliest memories that I was not going to be like the other children I knew. Nobody else among my classmates had fallen secretly in love with the Statue of Liberty. I did, because she was the biggest, most beautiful, most powerful image of womanhood I had ever seen. Nobody else was in love with the picture of Mozart on our music books. I was, because he looked to me, with his delicate features and long hair, like a child magically suspended between the sexes.

I also had a fully reasonable fear of the public consequences. God forbid that a policeman should ever pluck me from a table in a lesbian bar, shove me into a paddy wagon, and put my name on the roster of criminals. The bars underwent regular police raids in those days, and if you were visiting one that hadn’t been hit for a couple of months, you were in peril.

Nor could I face the prospect of having my children snatched from me. When you get down to cases, I and many other women feared that most of all. Lesbians were an illegal social category—not really yet a community—with no right to exist. Furthermore, if you were tagged with the lesbian label, you were typed beyond any hope of revealing yourself as a human being in full. Knowing you were gay, people thought they knew all there was to know about you, and what there was to know about you was that you were contaminated. There was a scarlet letter “L” on your chest. It was an age when homosexuality was a disease and stereotyping ran roughshod over real human beings. The women who came out under this kind of fire and, in effect, told the Establishment to stuff it are my heroes.

As for me, I went another way. I thought I could simply continue to live in my imagination, could use writing as a pressure valve when things got too difficult. This I did through six novels, writing in hours stolen from the relentless tasks of running a household and raising my children, so I could spend time with Laura, Beth, Beebo and the others. You’ve heard of fantasy friends; they were mine.

And then … I stopped writing. For some reason, that run of incredible emotional energy flamed out. It’s never been entirely clear to me why, but I actually felt emptied of stories for a while. It was a period in my life when my children needed a lot from me, we were moving frequently, and what strength I had was concentrated on a deteriorating marriage. I wanted to feed my mind on something absorbing, something that would take me out of myself. When Lord Byron’s friends asked him why in the world he had taken up the study of Armenian, he replied, “I found that my mind wanted something craggy to break upon.” That is just how it felt—something tough enough to distract me from the problems in my life for which I could see no resolution.

So I went back to graduate school. I earned a teaching credential, a master’s degree, and ultimately, a doctorate. It was an undertaking that consumed a whole decade from the mid-60s to the mid-70s, and led me to a position as a college professor, then a program director, and finally, an assistant dean in the university where I pursued my academic career. I did a lot of writing, of course, but it was all academic papers, memos, study materials, and professional letters. Ann Bannon had ceased to exist; she had become a phantom of my surprising past, almost as much a fictional character as Beebo Brinker herself. I thought I would never return to her, that no one knew she had ever had a life or written a word. The Greenwich Village of the 1950s and 60s had never seemed so far away.

And then the unimaginable happened. The New York Times publishing branch, Arno Press, wrote to me. They wanted permission to include four of my books in a library edition of gay and lesbian literature, under the rubric Homosexuality: Lesbians and Gay Men in Society, History and Literature. It was the first hint I had that Beebo Brinker and her creator had earned a life of their own.

I gratefully accepted the offer from the Times, and the hardcover edition was duly published. That, I thought, must be that; it was a sort of fluke. There was a glimmer of interest in the books as vignettes of a bygone time; indeed, in Ann Bannon herself as a sort of historical artifact. But the wave subsided. Several years went by, during which my children entered college, my long and difficult marriage ended, and my university career prospered.

And then it happened again. I was alone for the first time in my life in the early 1980s, living in a rental townhouse, when the telephone rang at a severely early hour one morning. It was Barbara Grier of Naiad Press, calling from Tallahassee, Florida. She had gotten my name from the people at Arno Press and tracked me down. I remembered Barbara’s name from the years when I was avidly reading any copies of The Ladder that I could get my hands on, and she was editing it as Gene Damon; I remembered reading about a bibliography of lesbian literature she had compiled, but I had never seen it. The name of the Naiad Press was entirely new to me.

But not for long. Barbara and her partner, Donna McBride, wanted to bring out the five books which had to do with Laura, Beth, and Beebo. It was my first inkling that my stories had been valued and preserved by a whole generation of women; that despite the crumbling condition of the old pulp paper and fading ink, they had survived on many bookshelves in many homes.

Barbara and I arranged to meet at a public appearance she had scheduled at Old Wives’ Tales Women’s Bookstore in San Francisco, where she introduced me to a cheering crowd. It was a wonderful, if confounding, re-introduction to the lesbian world. I met her and Donna again at a conference of the National Women’s Studies Association at Humboldt State University, where I signed the contract that resulted in the Naiad Press re-issuance of the books. First came a pocket book edition in 1983; then a trade paperback edition in 1986. I held my breath, fearing an indifferent reception from the public. But women all across the country embraced these stories of a now far-off generation of sisters. It was not just history; it was their history.

I have always been gratified that the books sold so well and rewarded the confidence that Barbara and Donna placed in them. The debt I owe them has been frequently acknowledged over the intervening years, but it bears repeating. They really brought Beebo back to life, and in so doing, gave Ann Bannon a presence in the community that she would not otherwise have had. It was a remarkable gift, and one for which I will always be thankful.

As a direct result of the Naiad editions, I was featured in the documentary movie, Before Stonewall, in the mid-1980s; and subsequently in the Canadian-produced film of lesbian lives made in the early 90s, Forbidden Love. Imagine coming back from the dead after more than twenty years and discovering that scholarly articles have been published about you, that there are master’s theses dealing with your work, and university literature classes teaching it.

In time, the Naiad Press editions ran their course while I labored in the groves of Academe. Almost a decade after the trade paperback edition came out, and as the remaining copies of that edition were being depleted, lightning struck again. This time it was the Quality Paperback Book Club, a subsidiary of Book-of-the-Month Club, which wanted to publish an omnibus edition of four of the books as part of their Triangle Classics: Illuminating the Gay and Lesbian Experience.

It seemed to me that nothing more could possibly happen to these books. They had enjoyed an unprecedented run. They had given me access to a vibrant young community, a whole new generation of men and women who listened as I lectured in venues across the country, and gave me an affectionate reception. They could have been judgmental and dismissive of the picture my books provided of “the way we were.” By and large, however, they were generous. They knew it hadn’t been easy, that we ourselves had been victimized back then by the very biases we denied, that somebody had to get the ball rolling. And those of us who had survived those days were taken to their hearts. They are fighting new battles for respect and acceptance, and it is good to know that there is an historical foundation to build on, that it wasn’t just the bad stuff happening “before Stonewall”; there was good stuff, too, and it had a far-reaching influence.

Now, Beebo is extending her welcome into the lives of yet another generation, thanks to the enterprise and faith of Cleis Press in San Francisco. It’s surprising to think that the 80s already seem distant to many young gays and lesbians, but to those entering adulthood today, they do. The old Naiad editions are themselves collector’s items. I have attended conventions of vintage paperback book collectors, and there they are, along with the really ancient Gold Medals, which seem like antiques now even to me.

Perhaps the longevity that I and my work have enjoyed is more a matter of endurance than any other quality. They say if you live long enough, the world will circle back around to have another look at you. It’s called “re-discovery,” and it’s an interesting process. As part of it, I have seen the butch/femme opposition, so potent in the 50s, rejected by women in the first excitement of the Women’s Movement, when strict equality was the order of the day; then accepted again as one of many possible models through which women may relate to one another. I’ve seen the Dream Machine in Hollywood go from the good-natured tolerance of gays in the early days, to gays as degenerate thugs in the 60s and 70s, to gays as romantic leads in our own time. There’s a long way to go, but we’re picking up speed, and the popular culture reflects the strength and confidence of an energized community.

When I lectured at the Eureka/Harvey Milk Branch of the San Francisco Public Library a year ago, I thanked a large, friendly audience for coming out in force to support me that evening. Every writer, every craftsman, every artist knows how much it means. And I closed with this little quote from British philosopher J.M. Thornburn, which should fire the creative spark in every heart:

“All the genuine deep delight in life lies in showing others the mud pies you have made. And life is at its finest when we confidingly recommend our mud pies to one another’s sympathetic consideration.”

Thank you, Gentle Readers, for your sympathetic consideration of my own mud pies, these stories of another age. May you forgive Beebo and her friends their faults, and enjoy them for their guts and humor.

Ann Bannon

Sacramento, CA

June 2001

The Beginning … (#ulink_36e8a57a-f844-55d9-85a8-9d0e56392613)

“Mmmm …” Beth murmured as Laura’s hands began to trace the curves of her back. “Oh, that’s marvelous.” She shivered a little and Laura trembled with her. “Under my pajamas, Laur.”

Warily, Laura lifted the pajama shirt and groped for the ripe smooth warmth beneath.

“Oh, yes …” Beth sighed.

And Laura’s hands descended to their enthralling task again, caressing the flawless hollows, the sweet shoulders. She was lost to reason now. She parted the hair that hid Beth’s neck and drew her fingers lightly over the white nape. She leaned closer, hardly aware that she moved. With a swift thrill of necessity she bent and kissed the softness for a long moment.

Then sudden fear pulled her up. She put her hand to her mouth and stared in terror at Beth. Beth lay perfectly still, a faint smile on her lips.

“Beth?” said Laura. “Beth?” The whisper quailed. “Oh, Beth! Say something! Forgive me! Say something! Are you mad at me?”

Beth whispered softly, “No.”

A wash of heat flooded Laura’s face. She bent over Beth and began to kiss her like a wild, hungry child, pausing only to murmur, “Beth, Beth, Beth….”

Beth rolled over on her back then and looked up at Laura, reaching for her, breathing hard and smiling a little, and her excitement consumed the last of Laura’s reserve. Her lips found Beth’s, and found them welcoming….

One (#ulink_17b491fe-4834-5574-982c-eafbd4cef213)

The big house was still, almost empty. Down the bright halls and in the shadowy rooms everything was quiet. Upstairs a few desk lights burned over pages of homework, but that was all.

There was one room in the sorority house, however, where no reading was going on. It was a big, warm room, meant for sprawling and studying and socializing in, like the others. Three girls shared it and two of them were in it now on this autumn Sunday night.

One was a newcomer. Her name was Laura and she had just finished moving all of her belongings into the room. It was a scene of overstuffed confusion, but at least she had somehow succeeded in squeezing all her things in and now there remained only the job of finding a place for them. Laura sat down to rest and worry about it. She tried to ignore the other girl.

Beth lay sprawled out on the studio couch with her head cushioned on a rambling pile of fat pillows at one end and her feet dangling over the other. She was drinking a Coke, resting the bottle on her stomach and letting it ride the rhythm of her breathing. She wore slim tan pants and a dark green sweatshirt with “Alpha Beta” stamped in white on the front. Her hair was dark, curly, and close-cropped.

Laura sat by choice in the stiff wooden desk chair, as if Beth were too comfortable and she could make amends by being uncomfortable herself. She was nervously aware of Beth’s scrutiny, and the sorority pledge manual she was trying to read made no sense to her. Beth seemed like all good things to Laura’s dazzled eyes: sophisticated, a senior, a leader, president of the Student Union, and curiously pretty. She had a well-modeled, sensitive face with features not bonily chic like those of a mannequin, but subtle, vital, harmonious. She wasn’t fashionably pretty but her beauty was healthy and real and her good nature showed in her face.