По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

Odd Girl Out

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

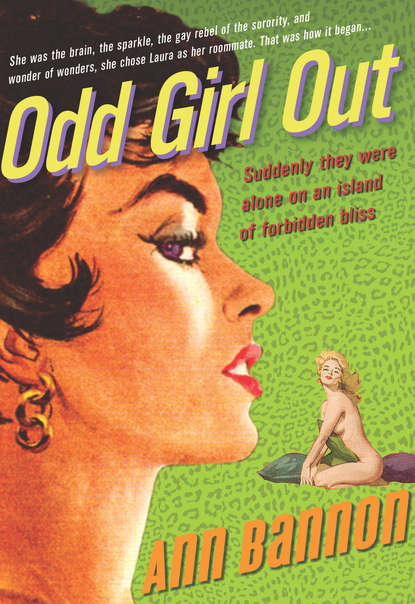

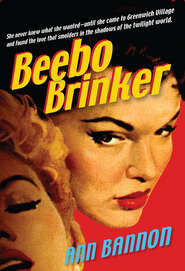

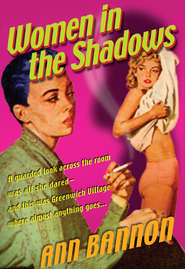

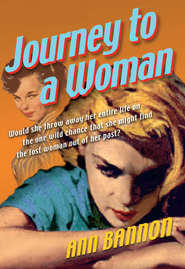

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerShe was the brain, the sparkle, the gay rebel of the sorority, and wonders of wonders, she chose Laura as her roommate. That was how it began…Suddenly they were alone on an island of forbidden blissTaking a pseudonym in the interest of privacy, Bannon wrote her first book, Odd Girl Out, as a coming-of-age novel that involved love between college sorority sisters. When an editor singled-out the school-girl romance as her story's most compelling feature, the book was re-written for a lesbian pulp fiction audience. Unlike most pulps, however, Bannon broke with tradition by avoiding sensationalistic plots in favour of emotionally engaged character development. Odd Girl Out enjoyed tremendous success, inspiring other ground-breaking works, most notably Beebo Brinker.“Odd Girl Out begins the saga of Laura, off on her own at college, appallingly shy and terminally polite…Laura meets Beth, whose brash straightforwardness and friendly attitude take the younger woman by storm, leading into an equally stormy affair” Metro Times

Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub12d7883-0929-55eb-8842-5785d075d590)

Title Page (#u499d5948-004b-5224-96c3-5b33b9041a22)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#u5d431c83-15b9-592a-bde3-63dc2f7a900e)

The Beginning … (#u3475689d-66bc-5993-8c82-762ecb327854)

Chapter One (#u42be6dca-4fc1-516c-90bb-3012acdaf19f)

Chapter Two (#u864de8de-ddef-56c5-8f88-521453e30312)

Chapter Three (#ucf6a2216-ea43-5e58-aaa7-2fdb6b92b4c8)

Chapter Four (#ua2cab555-f10e-593b-a5bd-328028217575)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#ulink_e6cb15b9-245a-57d2-9d7b-66ba21ed8b44)

I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of twenty-two to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience. I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just months behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world. There were millions living the same life; I was to be indistinguishable from them for many years, except for the fact, known to very few outside my immediate family, that I was the one who wrote a series of lesbian pulp paperback novels under the pen name of Ann Bannon. The stories came to be known as The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.

To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century, giving them an historical snapshot of the times. They have been revived in editions by five different publishers, once even coming out in a hard cover library edition. They have given comfort and courage to young gay people exploring their often difficult identities. They have even dismayed some in that community in our own time for their depiction of the stereotypes of the 1950s.

I sometimes shake my head and wonder, Who was that ingenuous twenty-two-year-old to be making these bold observations? Was she really me? Do I even know her anymore? Yes. She was me and I still recognize her. And I recall the characters I created, too. There they are in the pages written all those years ago: the girls I found so beguiling in college, the young women I met coming to the big city for the first adult adventures of their lives. In them, I still see the perplexities of identity, so pressing in youth, buried just beneath the sexual urgencies that drove us all. I see the older women, too, a little weary, a lot wary, many of them not that far in time from the utmost upheaval in their lives: World War II.

The world in the 1950s was changing in ways that were to lead inexorably to the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and yes, the Gay Rights Movement.

But those great social temblors were still in the future when I got my first look at a tranquil, almost rustic, Greenwich Village, with its parks, its crooked streets, its crafts shops, and its beckoning gay and lesbian bars. It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration. As I’ve often remarked, I felt like Dorothy throwing open the door of the old gray farm house and viewing the Land of Oz for the first time.

At that time, I was bubbling with stories of young arousal, but woefully lacking in what might be called “fieldwork experience.” I started to tell the story of a college sorority friend, heavily disguised of course, whose sexuality I suspected and who had aroused feelings in me that I both feared and enjoyed. I wanted to tell her story, and by telling hers to explore my own. I had absolutely no idea that I was on the cutting edge of anything, that I was about to catch a wave, or that others beside myself were engaged in similar creative tasks. I had read just two lesbian novels in my life: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Vin Packer’s Spring Fire.

It was to Vin Packer, then living and writing in New York, that I wrote with an appeal to help me get started. For her own reasons, she was kind enough to invite me to bring the unwieldy first draft of Odd Girl Out to New York. She would introduce me to her editor at Gold Medal Books, a major publisher of original pulp novels in the 1950s and 60s. The editor, Dick Carroll, took the book in hand. Within three days, he had read the manuscript. I waited in his office to hear the verdict.

“It’s pretty bad,” he said gently. “But I think it’s fixable. Go home, put this manuscript on a diet, and tell the story of the two girls. Then send it back to me.”

“The two girls?” Beth and Laura; I was dumbfounded. They had been no more than a distraction in the original story, based on girls I had known and admired in my college sorority. I was abashed to learn that my subtle little subplot had the makings of a novel, but all the other verbiage—what I had thought of as the novel—was smothering it.

I did go home, I did squeeze the story in half, I did write about Beth and Laura, amazed at the easy flow of the words. And months later, when Dick Carroll read it again, he published it, without changing a single word—without, in fact, even adding the word “lesbian,” which I had only just added to my vocabulary. It was not until thirty years later that I discovered that Odd Girl Out had been the second best-selling paperback book of 1957. I was off and running.

But how to follow up? Well, one writes what one knows. When I wrote Odd Girl Out, I knew college life. Now, I was determined to learn about gay life. New York was the focus of gay and lesbian culture in those days; it was electrifying to be there, even though my visits were necessarily brief, stolen from a conventional housewifely routine in Philadelphia. Once again, it was Vin Packer who helped me out and showed me around the Village; I will always be grateful for her help. I made the most of every moment. I visited every bar I could, and I got acquainted with some wonderful people. I walked the streets for hours, soaking it all up. On one occasion, I even walked home alone from a club at two in the morning. Such is the psychological armor of a twenty-two-year-old that I hadn’t the sense to be scared. I fully, frankly loved and embraced the Village.

But for all the exhilaration of these stolen moments, it was scary to write about lesbianism in the 1950s, the era of government repression, confining bias, and rigid social roles. I even worried that the FBI might be keeping a file on me. How did we get away with it, those of us writing these books? No doubt it had a lot to do with the fact that we were not even a blip on the radar screens of the literary critics. Not one ever reviewed a lesbian pulp paperback for the New York Times Review of Books, the Saturday Review, The Atlantic Monthly. We were lavishly ignored, except by the customers in the drugstores, airports, train stations, and newsstands who bought our books off the kiosks by the millions. The readers tended to enjoy them furtively; probably feeling as wary as I did when I wrote them. There was no public dialog about them in the media, either on their literary merits or their content, and that benign neglect provided a much-needed veil behind which we writers could work in peace.

And this had its benefits. Escaping public scrutiny as we did, we had a chance to talk about things that other writers usually handled—if they approached them at all—with a pair of tongs. We could take chances, we could be subversive, we could look at all the shameful, seductive, irresistible, delightful appeal of “the sex that dared not speak its name.” In a way, we were daredevils, protected by our unknown, uncredited, unsung noms de plume.

It took guts just to buy those books and confront the smirk on the face of the clerk at the cash register. People tried to disguise them in a pile of sundries they probably didn’t even need but bought anyway to distract attention from those eye-popping covers. I know—I was buying them, too. But once they had purchased them, they took the books home, read and re-read them, cherished them, and then hid them behind the fridge, in shoe boxes in their closets, under mattresses. It was a life-changing event if a spouse, a parent, or even a child found the books and challenged the reader. Nobody wanted to be shoved unceremoniously out of the closet, ready or not, particularly in that unforgiving time. But it did happen to many readers back then.

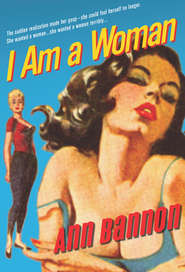

In Jaye Zimet’s book, Strange Sisters: the Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Penguin, 1999), for which I wrote the foreword, the colorful cover art for the lesbian pulps is given a showcase. Looking it over, I’m moved to wonder: How strange were our sisters? Even in the “exotic” and distant 1950s? Not very, truth to tell. Wonderful, but not strange, or at least, strange only on the covers of the books. When I was writing about them, I thought they were brave, passionate, gorgeous, and very, very cool. But not strange. And yet that word figures in dozens of the paperback book titles of the period as a sort of code for lesbian content, recognized by male and female readers alike.

Webster’s defines “pulp” as “tawdry or sensational writing.” In other words, sleaze. It never entered my head that I was writing sleaze; I was writing romantic stories of women in love. But it certainly entered the heads of the editors and publishers of the original pulps, and in a far from negative sense. Their job was to promote, market, and sell the books, and sleaze had a huge appeal. Furthermore, being men—most of them, anyway—they knew that the cover tease, showing a couple of desirable women who presumably would have interesting sex in the story, would lure a male audience and probably double their profits. Women readers could be relied on to read the covers iconically; men read them literally. Both would buy the books.

So the paperback publishers made money in what was basically the trashy trailer park of literature by lavishing curvy girls, lacy underwear, and heavy suggestions of sin and excess on their covers. That this frequently had little or no relationship to the actual characters and events in the stories was seldom a concern, any more than were the requests of the authors themselves with regard to cover illustration.

Ann Bannon

The classic 1950s love story from the Queen of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, and author of Odd Girl Out, I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman and Beebo BrinkerShe was the brain, the sparkle, the gay rebel of the sorority, and wonders of wonders, she chose Laura as her roommate. That was how it began…Suddenly they were alone on an island of forbidden blissTaking a pseudonym in the interest of privacy, Bannon wrote her first book, Odd Girl Out, as a coming-of-age novel that involved love between college sorority sisters. When an editor singled-out the school-girl romance as her story's most compelling feature, the book was re-written for a lesbian pulp fiction audience. Unlike most pulps, however, Bannon broke with tradition by avoiding sensationalistic plots in favour of emotionally engaged character development. Odd Girl Out enjoyed tremendous success, inspiring other ground-breaking works, most notably Beebo Brinker.“Odd Girl Out begins the saga of Laura, off on her own at college, appallingly shy and terminally polite…Laura meets Beth, whose brash straightforwardness and friendly attitude take the younger woman by storm, leading into an equally stormy affair” Metro Times

Odd Girl Out

Ann Bannon

www.spice-books.co.uk (http://www.spice-books.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub12d7883-0929-55eb-8842-5785d075d590)

Title Page (#u499d5948-004b-5224-96c3-5b33b9041a22)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#u5d431c83-15b9-592a-bde3-63dc2f7a900e)

The Beginning … (#u3475689d-66bc-5993-8c82-762ecb327854)

Chapter One (#u42be6dca-4fc1-516c-90bb-3012acdaf19f)

Chapter Two (#u864de8de-ddef-56c5-8f88-521453e30312)

Chapter Three (#ucf6a2216-ea43-5e58-aaa7-2fdb6b92b4c8)

Chapter Four (#ua2cab555-f10e-593b-a5bd-328028217575)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction: The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (#ulink_e6cb15b9-245a-57d2-9d7b-66ba21ed8b44)

I must have been the most naïve kid who ever sat down at the age of twenty-two to write a novel. It was the mid-1950s. Not only was I fresh from a sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had chosen a topic of which I had literally no practical experience. I was a young housewife living in the suburbs of Philadelphia, college graduation just months behind me, and utterly unschooled in the ways of the world. There were millions living the same life; I was to be indistinguishable from them for many years, except for the fact, known to very few outside my immediate family, that I was the one who wrote a series of lesbian pulp paperback novels under the pen name of Ann Bannon. The stories came to be known as The Beebo Brinker Chronicles.

To my continuing astonishment, the books have developed a life of their own. They were born in the hostile era of McCarthyism and rigid male/female sex roles, yet still speak to readers in the twenty-first century, giving them an historical snapshot of the times. They have been revived in editions by five different publishers, once even coming out in a hard cover library edition. They have given comfort and courage to young gay people exploring their often difficult identities. They have even dismayed some in that community in our own time for their depiction of the stereotypes of the 1950s.

I sometimes shake my head and wonder, Who was that ingenuous twenty-two-year-old to be making these bold observations? Was she really me? Do I even know her anymore? Yes. She was me and I still recognize her. And I recall the characters I created, too. There they are in the pages written all those years ago: the girls I found so beguiling in college, the young women I met coming to the big city for the first adult adventures of their lives. In them, I still see the perplexities of identity, so pressing in youth, buried just beneath the sexual urgencies that drove us all. I see the older women, too, a little weary, a lot wary, many of them not that far in time from the utmost upheaval in their lives: World War II.

The world in the 1950s was changing in ways that were to lead inexorably to the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and yes, the Gay Rights Movement.

But those great social temblors were still in the future when I got my first look at a tranquil, almost rustic, Greenwich Village, with its parks, its crooked streets, its crafts shops, and its beckoning gay and lesbian bars. It was love at first sight. Every pair of women sauntering along with arms around waists or holding hands was an inspiration. As I’ve often remarked, I felt like Dorothy throwing open the door of the old gray farm house and viewing the Land of Oz for the first time.

At that time, I was bubbling with stories of young arousal, but woefully lacking in what might be called “fieldwork experience.” I started to tell the story of a college sorority friend, heavily disguised of course, whose sexuality I suspected and who had aroused feelings in me that I both feared and enjoyed. I wanted to tell her story, and by telling hers to explore my own. I had absolutely no idea that I was on the cutting edge of anything, that I was about to catch a wave, or that others beside myself were engaged in similar creative tasks. I had read just two lesbian novels in my life: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Vin Packer’s Spring Fire.

It was to Vin Packer, then living and writing in New York, that I wrote with an appeal to help me get started. For her own reasons, she was kind enough to invite me to bring the unwieldy first draft of Odd Girl Out to New York. She would introduce me to her editor at Gold Medal Books, a major publisher of original pulp novels in the 1950s and 60s. The editor, Dick Carroll, took the book in hand. Within three days, he had read the manuscript. I waited in his office to hear the verdict.

“It’s pretty bad,” he said gently. “But I think it’s fixable. Go home, put this manuscript on a diet, and tell the story of the two girls. Then send it back to me.”

“The two girls?” Beth and Laura; I was dumbfounded. They had been no more than a distraction in the original story, based on girls I had known and admired in my college sorority. I was abashed to learn that my subtle little subplot had the makings of a novel, but all the other verbiage—what I had thought of as the novel—was smothering it.

I did go home, I did squeeze the story in half, I did write about Beth and Laura, amazed at the easy flow of the words. And months later, when Dick Carroll read it again, he published it, without changing a single word—without, in fact, even adding the word “lesbian,” which I had only just added to my vocabulary. It was not until thirty years later that I discovered that Odd Girl Out had been the second best-selling paperback book of 1957. I was off and running.

But how to follow up? Well, one writes what one knows. When I wrote Odd Girl Out, I knew college life. Now, I was determined to learn about gay life. New York was the focus of gay and lesbian culture in those days; it was electrifying to be there, even though my visits were necessarily brief, stolen from a conventional housewifely routine in Philadelphia. Once again, it was Vin Packer who helped me out and showed me around the Village; I will always be grateful for her help. I made the most of every moment. I visited every bar I could, and I got acquainted with some wonderful people. I walked the streets for hours, soaking it all up. On one occasion, I even walked home alone from a club at two in the morning. Such is the psychological armor of a twenty-two-year-old that I hadn’t the sense to be scared. I fully, frankly loved and embraced the Village.

But for all the exhilaration of these stolen moments, it was scary to write about lesbianism in the 1950s, the era of government repression, confining bias, and rigid social roles. I even worried that the FBI might be keeping a file on me. How did we get away with it, those of us writing these books? No doubt it had a lot to do with the fact that we were not even a blip on the radar screens of the literary critics. Not one ever reviewed a lesbian pulp paperback for the New York Times Review of Books, the Saturday Review, The Atlantic Monthly. We were lavishly ignored, except by the customers in the drugstores, airports, train stations, and newsstands who bought our books off the kiosks by the millions. The readers tended to enjoy them furtively; probably feeling as wary as I did when I wrote them. There was no public dialog about them in the media, either on their literary merits or their content, and that benign neglect provided a much-needed veil behind which we writers could work in peace.

And this had its benefits. Escaping public scrutiny as we did, we had a chance to talk about things that other writers usually handled—if they approached them at all—with a pair of tongs. We could take chances, we could be subversive, we could look at all the shameful, seductive, irresistible, delightful appeal of “the sex that dared not speak its name.” In a way, we were daredevils, protected by our unknown, uncredited, unsung noms de plume.

It took guts just to buy those books and confront the smirk on the face of the clerk at the cash register. People tried to disguise them in a pile of sundries they probably didn’t even need but bought anyway to distract attention from those eye-popping covers. I know—I was buying them, too. But once they had purchased them, they took the books home, read and re-read them, cherished them, and then hid them behind the fridge, in shoe boxes in their closets, under mattresses. It was a life-changing event if a spouse, a parent, or even a child found the books and challenged the reader. Nobody wanted to be shoved unceremoniously out of the closet, ready or not, particularly in that unforgiving time. But it did happen to many readers back then.

In Jaye Zimet’s book, Strange Sisters: the Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Penguin, 1999), for which I wrote the foreword, the colorful cover art for the lesbian pulps is given a showcase. Looking it over, I’m moved to wonder: How strange were our sisters? Even in the “exotic” and distant 1950s? Not very, truth to tell. Wonderful, but not strange, or at least, strange only on the covers of the books. When I was writing about them, I thought they were brave, passionate, gorgeous, and very, very cool. But not strange. And yet that word figures in dozens of the paperback book titles of the period as a sort of code for lesbian content, recognized by male and female readers alike.

Webster’s defines “pulp” as “tawdry or sensational writing.” In other words, sleaze. It never entered my head that I was writing sleaze; I was writing romantic stories of women in love. But it certainly entered the heads of the editors and publishers of the original pulps, and in a far from negative sense. Their job was to promote, market, and sell the books, and sleaze had a huge appeal. Furthermore, being men—most of them, anyway—they knew that the cover tease, showing a couple of desirable women who presumably would have interesting sex in the story, would lure a male audience and probably double their profits. Women readers could be relied on to read the covers iconically; men read them literally. Both would buy the books.

So the paperback publishers made money in what was basically the trashy trailer park of literature by lavishing curvy girls, lacy underwear, and heavy suggestions of sin and excess on their covers. That this frequently had little or no relationship to the actual characters and events in the stories was seldom a concern, any more than were the requests of the authors themselves with regard to cover illustration.