По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

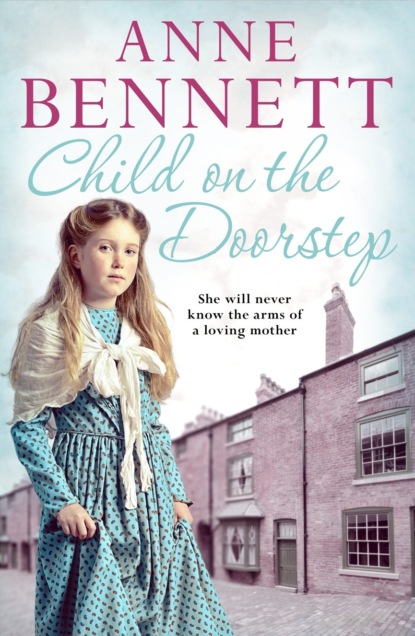

Child on the Doorstep

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘That will be better for you, Granny,’ she said. ‘Now the summer’s here you won’t need the warmth of the fire so much.’

It worked a treat, for as Mary waved at neighbours going past many would pop in and have a word. Some days she couldn’t cope with much more than that, and on her vaguer days, if she wasn’t always absolutely sure who everyone was, no one seemed to mind.

‘God, this growing old is a bugger,’ Norah said one morning, meeting Angela coming home from her cleaning job at the pub.

‘But the alternative is worse,’ Angela answered.

‘That’s true,’ Norah agreed. ‘And God knows we might all be the same some day.’

Angela knew that was all too true and she also knew ‘the alternative’ couldn’t be put off for ever. She wondered how much Connie was aware of. But Connie knew her grandmother’s life was ebbing away and knew also that her death would leave a big hole in her life because Mary had been a constant in her life since the day she’d been born.

There had been a time when Connie was younger when her mother had gone away. She had gone to Ireland and, though her grandmother loved talking about things past, she was always very vague about that time. Mary said Angela had had to go to Ireland and help a family out after the mother died, and yet she had previously told her that her mother had no relatives to take her in and so that was why she stayed with the McCluskys. And whoever the family had been that had called on her mother’s help, her grandmother said she couldn’t recall their name. Connie had missed her mother a great deal and been very glad her grandmother was there, a solid loving presence who soon would be no more.

The summer slipped by far too quickly. Angela could scarcely believe it was September and the schools were open again. Mary’s chair was once more moved closer to the fire because those autumn days were windy ones and it was hard to keep the house draught-free. Despite the heat from the fire, Mary seemed constantly cold for, as the wind gusted down the road, it seeped through the ill-fitting windows and snaked under the door and along the floor, attacking the backs of Mary’s legs like a cold flannel.

Angela, seeing how cold Mary was, brought down an extra cardigan and a blanket to wrap around her, knowing it was bound to get much colder still. She was glad she had the money to lay in enough coal and buy good food and plenty of it to help them all, and Mary in particular, cope with the drop in temperature. She had worried about leaving her mother on her own while she worked once Connie returned to school, but she needn’t have worried for Mary was seldom alone as one of the neighbours would invariably pop in to see her. And at the weekend, when Angela worked the bar at the Swan in the evenings, Connie could stay up later because she hadn’t school in the morning. Mary didn’t keep late hours anyway and so the girl could easily help her grandmother to bed.

Angela knew how lucky she was. The house and area she lived in was not great but she was blessed with good, kind neighbours who cared for one another and a daughter and mother in a million. If Barry had returned from the war hale and hearty life would have been just perfect, but, as she reflected, few people achieve perfection in this life. She was content, only now she had met Stan’s son, Daniel, she found herself wishing Stan had survived too. How proud he would have been of that young man, who, if he’d had the chance to know him, would have realised what a great father he would have been.

But there was nothing she could do about that, and besides, Daniel hadn’t been near them since the early summer when they had put him straight about any misconceptions he’d had and told him the truth about his father. In the end he had returned home and taken a job in the bank Roger had secured for him that he definitely didn’t want. Daniel was taking the line of least resistance for the sake of a quiet life, and yet she couldn’t blame him. Betty and Roger had brought him up and made sure he had a good education, and he owed them something for that. But he couldn’t spend the rest of his life being grateful for the good start they had given him, and she hoped he’d realise that eventually.

Soon, Angela had more to worry about than Daniel, for the winter had taken hold of the city by mid-November. The grey days were bone-chillingly cold and the houses so draughty and damp that it was hard to keep them adequately heated. Mary, not usually a complainer, seemed constantly cold and one day, coming in from work, Angela saw her mother’s cheeks were glowing red. Though she still said she was cold, her skin was burning up.

‘You have a fever,’ Angela said. Her voice was calm and controlled but inside she was panicking. ‘Bed is the best place for you. You must have my bed for now and I will take your place in the attic with Connie.’

‘No need for such fuss.’

‘I’m not fussing, Mammy, but being sensible,’ Angela insisted. ‘Now I’ll just warm it up for you and bring down your things from the attic.’

Mary might have argued further but she was overtaken by a spasm of coughing and Angela crossed to the fire. It was almost out, even though Connie had filled a scuttle with coal before she had left for school. Usually Mary kept a good fire going but at that moment Angela was glad that she hadn’t. She removed two firebricks with the tongs and wrapped them in a cloth she had ready, running up and slipping them between the sheets on her bed.

As she went up to the attic for Mary’s things, Angela remembered for a moment the devastating Spanish flu that had rampaged through the whole world as the Great War came to an end. That epidemic had been indiscriminate and there was no cure – it depended on the individual’s capacity to fight it – and at its height it affected a fifth of the world’s population. It had raged on for two years and while some people died within days, when their lungs filled with fluid and they suffocated to death, others lingered on but still died just the same. By the time it had abated it had claimed fifty million lives, even more than the Great War, which had claimed sixteen million. Families were wiped out, many of the men who had survived a war of such magnitude lost their lives to the influenza and everyone had been fearful.

Many people had avoided crowds, shunning picture palaces and theatres, but children had had to go to school and Angela had sent Connie fearfully, knowing she wouldn’t want to live if she were to lose her daughter. But she had come through unscathed and so had Angela and Mary. Angela was determined Connie wasn’t going to catch anything from Mary now, and so she decided to adopt the strategies people had used before to try and combat the spread of the flu in 1918.

With her mother tucked up nice and warm in bed, Angela hung a sheet she’d soaked in disinfectant across the doorway. She vowed to wash her hands with carbolic soap and warm water whenever she dealt with Mary and would scald any plate, bowl, cup or cutlery she used.

A little later, after popping up to see Mary, who was lying in a fretful sleep, she went down to the presbytery and asked the priest to call. Then she went to see Paddy Larkin at the pub to tell him of her mother’s collapse. Paddy was upset at the news for he thought a lot of Mary and so did Breda, and she told Angela not to worry about anything.

‘If Maggie can take on all the cleaning, I’ll give Paddy a hand in the pub at the weekend,’ she said. ‘Your place is with Mary now.’

Angela knew it was. Connie was home from school when the priest came, distressed to see her grandmother so ill. She watched her fighting for every breath and her anxious eyes met her mother’s. They both thought that at any moment Mary would give up the struggle to breathe and slip away. The priest thought the same as he administered the Last Rites, though he didn’t speak of it.

There was little Angela could do to ease Mary’s symptoms, though a warmed flannel sprinkled with camphorated oil eased the pain in her chest a little. Mary didn’t want Angela to call the doctor, for she claimed it was just a cold. Angela knew it was more serious than that and, when Mary refused to eat because it hurt so much to swallow, she said she was calling the doctor and that was the end of it.

The doctor confirmed that Mary had a severe chest infection and a quinsy in her throat. He fully approved of the precautions Angela was taking, for he said Mary’s flu was very infectious. He prescribed a poultice for her to make up and lay on Mary’s throat, as hot as she could stand, and he made up a bottle to help the cough that was further irritating her throat.

He could do little else. He knew the old lady was very ill and, with her heart weakened by the attack she had when she received the telegram telling her of the death of her son, he didn’t think she had much of a chance of recovering from this. He didn’t share this with Angela. He knew she was no fool and would know how seriously ill Mary was without having it spelt out for her.

Angela did know, and as the days unfolded she couldn’t believe how Mary was hanging on. December wasn’t very old when she fought off the debilitating fever, and the hacking cough that had once seemed to shake every bone in her body eased a little, as did her sore throat, so that she was able to swallow the broths Angela soon made ready for her. As the worst effects of the chest infection left her, strangely her mind seemed more lucid than it had been for many months and one day she said to Angela, ‘You should be at work.’

‘Work will keep,’ Angela said. ‘They’re coping without me just now.’

‘Maybe they will find they can cope without you permanently.’

Angela smiled. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I have no fears on that score. They knew my place was with you when you were so ill. I am delighted to see you so much better. Sometimes I wished I could have breathed for you.’

Mary gave a wry smile. ‘If I had thought of that, I might have wished you could too,’ she said and then she added, ‘Christmas is always a bad time for you, isn’t it?’

‘Of course it is.’

‘Connie has noticed.’

‘I can’t help that,’ Angela said.

‘I told her it’s because you still miss her daddy and you feel it more at Christmas,’ Mary said.

‘Well, you didn’t tell a lie anyway,’ Angela said. ‘I do miss Barry. Every day I miss him, but I go on because I must, but what I did nine years ago, God, it eats away at me, Mammy. God may forgive me, but I will never forgive myself. I condemned my own child to misery and deprivation and it doesn’t help that at the time there was no alternative and there still isn’t. I sacrificed my own child, my baby, so that others wouldn’t be hurt, and all I could give her was the locket that they probably won’t let her keep. They might have even stolen it from her.’

Angela wasn’t aware of when she began to cry. Mary hadn’t the strength to put her arms around Angela as she wanted to and so she contented herself with patting her hand. And eventually Angela went on, ‘I’ve never confessed, you know, Mammy. It was the worst thing I have ever done in my life and I could not bring myself to tell any priest. I asked God to punish me and He took Barry from me. When I saw you collapsed on the floor with the telegram in your hand I thought He had taken you too. Oh God, that would have been a heavy price to pay.’

‘Oh my darling girl,’ Mary said, her voice breaking with emotion. ‘I don’t know if God does things like that, but you really need to get absolution for your own sake.’

‘Mammy, I can’t,’ Angela protested. ‘Can you imagine what would happen if I did that? I know Father Brannigan can’t tell anyone what I say in confession, but that won’t stop him berating me, for he knows my voice. He will know the identity of the person the other side of that grille telling him of the dreadful, heinous thing I did and why, and that would be hard to bear. And what if someone overheard what I said in the confessional box, or heard him telling me off later and put two and two together? No, Mammy, I am not going down that road.’

‘How about St Chad’s? No one knows you there.’

Angela thought of the kindly looking priest that she knew people called Father John at St Chad’s, the same man who had unknowingly protected her that dreadful Christmas Eve nine years before.

‘I couldn’t,’ she said.

‘Why not?’ Mary demanded. ‘That night, I know you took shelter there, but did he see you go into the church?’

Angela shook her head. ‘I doubt it. I mean, he didn’t seem to be in the main body of the church when I went in. I only saw him when the men from the house came looking for me. They admitted to him they hadn’t seen me go in either, but they were checking everywhere because it was as if I had disappeared into thin air. Anyway, he sent them packing and if he had seen me come in in the agitated state I was in, I’m sure he would have spoken to me. I mean, the church wasn’t empty as I told you, but it wasn’t full like it is for Mass. There were only a handful of people there and, thinking about it, he probably knew most of them.’

‘So why won’t you go there? You said he looked kindly.’

‘I have heard he’s kind,’ Angela said. ‘But I might make him feel a bit of a fool, because I’d say he’d work out who I was, because I’ll have to tell him everything if I want him to give me absolution. How could I tell a man, any man, never mind a priest, about that attack?’

‘Angela, you cannot blame yourself,’ Mary said. ‘None of it was your fault.’

‘D’you know, Mammy,’ Angela said rather sadly. ‘In the general scheme of things it hardly seems to matter whose fault it was.’

‘God knows, and that’s the truth,’ Mary said.

‘You know, when Barry died, I thought about enquiring after the child, or even bringing her here where she belongs to be brought up by her mother.’

‘What stopped you?’