По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

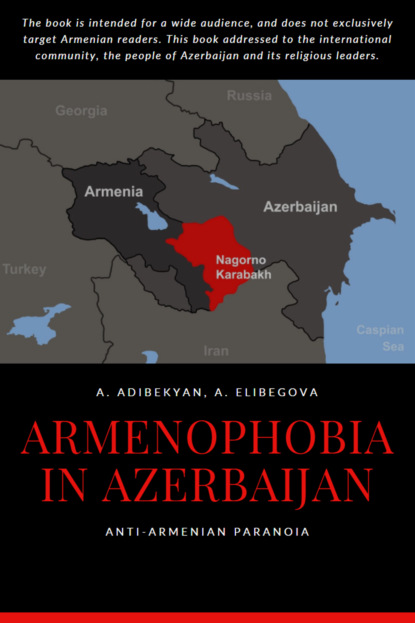

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The other church in the city, a Russian church, is used as a sports facility. The church was looted during the Armenians pogroms of 1905–1906. It is known that in 1907–1912, the Armenians of Qazakh expressed their desire to restore the fence of the church. Later, the church was raided by Tatars in 1918.

Ganja (Gandzak):

The church Surb Astvatsatsin (The Holy Mother of God) dating to the 18th century was turned into a club; the church Surb Astvatsatsin Cholaga (The Holy Mother of God) dated 8-10th centuries was pulled down; the church Surb Gevorg of the 19th century was demolished; the church Surb Grigor Lusavorish (Zham) dating to 1869 was pulled down; the church Surb Kirakos dating to 1913 was pulled down; the church Surb Sargis (17-18th centuries) was turned into a museum.

In Azerbaijan, all the restoration works of Armenian monuments sought to completely erase any Armenian inscriptions and any traces of the Armenian architecture. Under the Soviet regime, no Armenian architectural monuments were restored (or at least categorized) in either Nagorno-Karabakh, or on the entire territory of Azerbaijan. This fact may by no means purport to reflect the religious intolerance and oppression of the communists, since all sparse monuments of Islamic culture (incidentally, all of them dated back to no earlier than the 18th century) on the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh were fully restored.

The period of the Azerbaijani administration of Nagorno-Karabakh and the years of Azerbaijan’s armed aggression against the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh saw the destruction, blasting and complete demolition of 167 churches, 8 monastery complexes, 123 Armenian historical cemeteries and 47 settlements. Over 2,500 khachkars (cross-stone memorials) of high artistic merit and over 10,000 tombstones with epigraphs were dismantled for building material. 13 historical and archaeological sites were bulldozed to the ground. Monuments in the caves of Tsakhach, Mets Taghlar and Azokh were blown up. The khachkars, tombstones, churches and fortress walls (5-8th centuries) in the settlements of Mokhrablur, Sarashen, Aknaberd and Manadzor were ruined. Most of the wall of the unique fortress Mayraberd (16-17th centuries) was pulled down.

The above examples are, regrettably, incomplete, but are illustrative of the terror tactics employed against the Armenian cultural heritage in the region aiming to completely erase any vestiges of their historical presence on the territory of today’s Azerbaijan.

15. Mythologization of «genocides»

The psychological warfare frequently includes the use of myths.

The myth is the information which accounts for the origins and further development of various phenomena based on real or fictitious events or facts, with subsequent exaggeration of distortion of the cause and effect relations.

The human perception of the surrounding reality through myths is based on beliefs and opinions held by representatives of a specific culture, ethnic or social group rather than scientific knowledge.

People usually resort to social myths, which are warped notions of the reality deliberately inculcated in the public mind to shape the required social responses. The most singular element about social myths is that the bulk of the society views them as a natural state of affairs rather than pieces of fiction. As a rule, under the impact of social myths, the history of origin and development of states and ethnic groups becomes distorted to such extent that its impartial analysis is possible only through critical juxtaposition of various sources.

Specialists consider that myths have the capacity to:

• affect simultaneously the intellectual and emotional aspects of the human consciousness. This makes people believe in the reality of the mythical content;

• turn a hyperbolic depiction of an individual case into an ideal model of the desired line of conduct. It is thanks to this peculiarity that the content of myths can affect the human conduct;

• rely on a specific tradition existing in the society.

Myths are an efficient tool for manipulating the consciousness. A myth taken alone has little meaning. However, when inculcated and deeply ingrained in the minds of the people, a myth can substitute (provided certain conditions are met) the reality for a long time. As a result, the recipient perceives the reality in line with how the myth is interpreted and therefore acts based on such perception. The convenience of the myth resides in its capacity to simplify the reality relieving the recipient of any need for intense (and frequently painful) thinking to comprehend the surrounding world.

In the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, genocide means “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”.

March 26, 1998 marked the official starting point for mythologization of the “Azerbaijani genocide” as the Azerbaijani ex-president Heydar Aliyev officially instituted the ‘day of genocide of the Azerbaijanis’.

On March 27, 2003, Aliyev, Sr. stated in his speech:

The massive settlement of Armenians on our historical lands after the division of Azerbaijan between Russia and Iran, the massacre of Azerbaijanis perpetrated by Armenian Dashnaks in 1905 and 1918, handing over Zangezur to Armenians in the 1920s, the creation of an Armenian autonomy on the territory of Karabakh, the deportation of our compatriots from Armenia in 1948–1953… new territorial claims of Armenia to Azerbaijan in the late 1980s – all led to a full-scale war, occupation of 20 percent of Azerbaijani lands by the Armenian armed groups and made about 1 million of our compatriots refugees and internally displaced persons.

The “genocide of 1905 in Baku”, the “genocide of 1918 in Baku and Guba”, the “genocide of 1988–1990” and the “genocide of Khojaly” are the four major “genocides” intensely trumpeted by the Azerbaijani propaganda. There are also other secondary and minor “genocides”: purported to have been perpetrated in Zangezur, Karabakh, Shemakh, Kyurdamir, Salyan, Lankoran, Kafan, Gugark, Sisian, Agdaban, Baghanis-Ayrum, Masis, etc.

The geography of the Azerbaijani genocides is quite extensive, with matching time frames. Only one thing remains without change: perpetrators and organizers. This role is traditionally reserved for Armenians. Let us examine the psychological prerequisite for the mythologization of “Azerbaijani genocides”.

The scholar Yuri Lotman in his article on semiotics and typology of the culture notes that each culture creates a mythologized image as its ideal self-portrait.

In his turn, W. Wundt notes that the language, myths and customs represent common spiritual phenomena so closely fused together that one is unthinkable without the other. <…> The customs express through deeds the same views on life that rest on myths and become public through language. These deeds in their turn further enhance and elaborate the perceptions that they stem from.

It must be pointed out that the mythologization of genocides is a cultural product of today’s Azerbaijani society and is a manifestation of latent aggression.

“Aggression is the consequence of such conduct that has for objective as its targeted response the infliction of a damage to the person it is aimed against. The aggression may not always be exhibited openly; it can manifest itself through fantasizing, dreaming or even through a thoroughly deliberated retaliation plan; it can be directed against the purported cause of frustration, be redirected against a completely innocent target or even own self”.

Besides, another psychological phenomenon can be at play here termed ‘mirroring’ and amounting to reproduction with varying degrees of adequacy the traits, structural characteristics and relations of other objects. This comes to say that in this case, the historical fact of the Armenian Genocide called for an “Azerbaijani genocide of their own” to match Armenians.

The head of the Assistance to Development of Public Relations NGO, Shelale Hasanova in her interview to the Day.az information agency pointed out the mainstays of the Azerbaijani propaganda: “We suffered through four genocides in a single century and we remained unbroken; we survived and we gained independence and we now become integrated into the world community. This is what we must speak and write about not only on the Genocide Memorial Day but during the history classes in schools, at international conferences and during various political actions. I shall remind you these four genocides: the genocide of Azerbaijanis in 1905–1907 in Western Azerbaijan

and in Baku, the genocide of 1918–1920 perpetrated by Dashnaks in Armenia and Azerbaijan, the genocide of 1988 when militant nationalists of the Soviet Armenia banished Azerbaijanis from the lands of Oghuz Turks by torturing and burning them alive. And finally, the forth genocide was perpetrated by Armenian armed bands in Khojaly”.

This anti-Armenian propaganda campaign enlists the assistance of all political and civil institutes. For instance, Elmira Suleymanova, the Azerbaijani Ombudsman, stated that “as a result of a deliberate genocidal policy, ethnic cleansings and deportations perpetrated by Armenians and their supporters against Azerbaijanis over the past two centuries, our people had to endure dreadful ordeals… A total of some 700 thousands of our compatriots were killed”.

There is no need to dwell in detail on every single attempt at falsification of historic events of the region by the Azerbaijani propaganda. It will suffice to focus on the two most circulated examples, that of Guba and Khojaly.

“The genocide of Guba”

In 2007, during drilling works for the renovation of a stadium in Guba, a mass grave of unknown origin was found on the site of a trash dump. Only 35 human skeletons could be lifted to the surface in their entirety. To this day, no result of any archaeological research or expert appraisal on the origin of these remains has been published. Also, no concomitant evidence has been made available.

Meanwhile, on December 30, 2009, the president Ilham Aliyev issued a decree on creation of a “genocide memorial complex” in Guba. Depending on the interests currently at stake, the remains are attributed to Jews or Lezgins or simply Muslims. However, Armenians are invariably cast in the role of the perpetrators.

The text of the decree reads as follows:

At the outset of the past century, as a result of a policy of mass ethnic cleansings and aggression perpetrated by armed bands of Armenian Dashnaks on Azerbaijani lands – in Baku, Guba, Karabakh, Shemakh, Kyurdamir, Salyan, Lankaran and other regions, tens of thousands of innocent Azerbaijanis were killed; one of the most tragic genocidal acts of the 20th century was committed against our people. In April-May 1918, in the Guba uyezd only, 122 villages were completely destroyed. The mass grave in the city of Guba revealed that as a result of the genocide, along Azerbaijanis slain with boundless ferocity and extreme cruelty, thousands of Lezgins, Jews, Tats and representatives of other national minorities were exposed to violence.

What did really happen in Guba? Immediately upon the discovery of the grave in Guba, the speaker of the Azerbaijani parliament Oktay commissioned the director of the History Institute, member of the parliament, Yagub Mahmudov to retain foreign anthropologists and compile an official document “on the mass killing of Azerbaijanis by Armenians at the outset of the past century”. However, foreign experts never showed up in Guba, and the remains discovered there were not given any independent appraisal at least to determine their temporal dimension.

The late president of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Mahmud Kerimov, did not exclude that the remains of Guba might both stem from a mass killing and a mass epidemic.

Meanwhile, Gahraman Agayev, the head of the expedition mounted by the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, stated in relation to the discovery of about 200 skulls: “The researchers concluded that the grave is a result of a genocide perpetrated by Armenians in Guba. A phantom letter by Stepan Shahumyan addressed to Hamazasp which has never been published by the Azerbaijani side is quoted by Agayev as a “compelling” piece of evidence.

Agayev’s claim that the time of the death was accurately established (“The massacre occurred between May 3 and 10”) is equally preposterous. The same can be said about his assertion that “it has been established based on anthropological investigation of skulls that apart from Azerbaijanis, Jews and Lezgins suffered physical extermination in 1918”. Agayev also passed over in silence the revolutionary method that must have been contrived by the Azerbaijani scientists for unraveling the precise ethnicity of the remains.

Yet, his colleague, Maisa Rahimova, the director of the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, seems to be in the same boat as she claims that “anthropological research confirmed that these people were Muslims”

Notice must be taken of the fact that a participant of the same expedition, Asker Aliyev, Candidate of Historical Sciences, clearly states: “Only 35 skeletons could be identified from among a multitude of skulls and children’s bones. No hair, vestiges of clothes or objects were found in the wells”. This means that any assertion about the religious affiliation of the persons, whose remains were found, is not only unprofessional but downright fatuous.

In January 2012, professor Levon Yepiskoposyan, Doctor of Biology, addressed a letter to the president of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, academician Mahmud Kerimov offering to carry out a qualified international expert appraisal of the human remains found in Guba in order to discover scientifically the truth about the mass graves of Guba. In February 2010, the professor came up with another proposal to allow Armenian specialists to take part in a joint anthropological and genetic expert examination of the remains found in Guba; however, his letter remained unanswered.

Meanwhile, Hayk Demoyan, the director of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, notes that there are archive materials proving that the Armenian population of Guba was exposed to violence from the local Tatar bands in 1918, and the number of Armenian victims corresponds to the number of skeletons found at the burial site.

Here is one such testimony. In the late April 1918, Gelovani, the commissar of the city and the region of Guba, sent a telegram to Korganov, the chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee, containing the following: “Today, on April 24, I released 115 Armenians who were jailed in the prison of Guba. They all were divested of their property. I took measures to have their property restituted. They are asking for financial assistance from the Armenian National Counsel. Please, send it to my address as soon as possible. The pecuniary situation is critical… apart from the city of Guba, Armenians are held captive also in other places. I am taking measures towards their liberation”.

Ganja (Gandzak):

The church Surb Astvatsatsin (The Holy Mother of God) dating to the 18th century was turned into a club; the church Surb Astvatsatsin Cholaga (The Holy Mother of God) dated 8-10th centuries was pulled down; the church Surb Gevorg of the 19th century was demolished; the church Surb Grigor Lusavorish (Zham) dating to 1869 was pulled down; the church Surb Kirakos dating to 1913 was pulled down; the church Surb Sargis (17-18th centuries) was turned into a museum.

In Azerbaijan, all the restoration works of Armenian monuments sought to completely erase any Armenian inscriptions and any traces of the Armenian architecture. Under the Soviet regime, no Armenian architectural monuments were restored (or at least categorized) in either Nagorno-Karabakh, or on the entire territory of Azerbaijan. This fact may by no means purport to reflect the religious intolerance and oppression of the communists, since all sparse monuments of Islamic culture (incidentally, all of them dated back to no earlier than the 18th century) on the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh were fully restored.

The period of the Azerbaijani administration of Nagorno-Karabakh and the years of Azerbaijan’s armed aggression against the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh saw the destruction, blasting and complete demolition of 167 churches, 8 monastery complexes, 123 Armenian historical cemeteries and 47 settlements. Over 2,500 khachkars (cross-stone memorials) of high artistic merit and over 10,000 tombstones with epigraphs were dismantled for building material. 13 historical and archaeological sites were bulldozed to the ground. Monuments in the caves of Tsakhach, Mets Taghlar and Azokh were blown up. The khachkars, tombstones, churches and fortress walls (5-8th centuries) in the settlements of Mokhrablur, Sarashen, Aknaberd and Manadzor were ruined. Most of the wall of the unique fortress Mayraberd (16-17th centuries) was pulled down.

The above examples are, regrettably, incomplete, but are illustrative of the terror tactics employed against the Armenian cultural heritage in the region aiming to completely erase any vestiges of their historical presence on the territory of today’s Azerbaijan.

15. Mythologization of «genocides»

The psychological warfare frequently includes the use of myths.

The myth is the information which accounts for the origins and further development of various phenomena based on real or fictitious events or facts, with subsequent exaggeration of distortion of the cause and effect relations.

The human perception of the surrounding reality through myths is based on beliefs and opinions held by representatives of a specific culture, ethnic or social group rather than scientific knowledge.

People usually resort to social myths, which are warped notions of the reality deliberately inculcated in the public mind to shape the required social responses. The most singular element about social myths is that the bulk of the society views them as a natural state of affairs rather than pieces of fiction. As a rule, under the impact of social myths, the history of origin and development of states and ethnic groups becomes distorted to such extent that its impartial analysis is possible only through critical juxtaposition of various sources.

Specialists consider that myths have the capacity to:

• affect simultaneously the intellectual and emotional aspects of the human consciousness. This makes people believe in the reality of the mythical content;

• turn a hyperbolic depiction of an individual case into an ideal model of the desired line of conduct. It is thanks to this peculiarity that the content of myths can affect the human conduct;

• rely on a specific tradition existing in the society.

Myths are an efficient tool for manipulating the consciousness. A myth taken alone has little meaning. However, when inculcated and deeply ingrained in the minds of the people, a myth can substitute (provided certain conditions are met) the reality for a long time. As a result, the recipient perceives the reality in line with how the myth is interpreted and therefore acts based on such perception. The convenience of the myth resides in its capacity to simplify the reality relieving the recipient of any need for intense (and frequently painful) thinking to comprehend the surrounding world.

In the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, genocide means “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”.

March 26, 1998 marked the official starting point for mythologization of the “Azerbaijani genocide” as the Azerbaijani ex-president Heydar Aliyev officially instituted the ‘day of genocide of the Azerbaijanis’.

On March 27, 2003, Aliyev, Sr. stated in his speech:

The massive settlement of Armenians on our historical lands after the division of Azerbaijan between Russia and Iran, the massacre of Azerbaijanis perpetrated by Armenian Dashnaks in 1905 and 1918, handing over Zangezur to Armenians in the 1920s, the creation of an Armenian autonomy on the territory of Karabakh, the deportation of our compatriots from Armenia in 1948–1953… new territorial claims of Armenia to Azerbaijan in the late 1980s – all led to a full-scale war, occupation of 20 percent of Azerbaijani lands by the Armenian armed groups and made about 1 million of our compatriots refugees and internally displaced persons.

The “genocide of 1905 in Baku”, the “genocide of 1918 in Baku and Guba”, the “genocide of 1988–1990” and the “genocide of Khojaly” are the four major “genocides” intensely trumpeted by the Azerbaijani propaganda. There are also other secondary and minor “genocides”: purported to have been perpetrated in Zangezur, Karabakh, Shemakh, Kyurdamir, Salyan, Lankoran, Kafan, Gugark, Sisian, Agdaban, Baghanis-Ayrum, Masis, etc.

The geography of the Azerbaijani genocides is quite extensive, with matching time frames. Only one thing remains without change: perpetrators and organizers. This role is traditionally reserved for Armenians. Let us examine the psychological prerequisite for the mythologization of “Azerbaijani genocides”.

The scholar Yuri Lotman in his article on semiotics and typology of the culture notes that each culture creates a mythologized image as its ideal self-portrait.

In his turn, W. Wundt notes that the language, myths and customs represent common spiritual phenomena so closely fused together that one is unthinkable without the other. <…> The customs express through deeds the same views on life that rest on myths and become public through language. These deeds in their turn further enhance and elaborate the perceptions that they stem from.

It must be pointed out that the mythologization of genocides is a cultural product of today’s Azerbaijani society and is a manifestation of latent aggression.

“Aggression is the consequence of such conduct that has for objective as its targeted response the infliction of a damage to the person it is aimed against. The aggression may not always be exhibited openly; it can manifest itself through fantasizing, dreaming or even through a thoroughly deliberated retaliation plan; it can be directed against the purported cause of frustration, be redirected against a completely innocent target or even own self”.

Besides, another psychological phenomenon can be at play here termed ‘mirroring’ and amounting to reproduction with varying degrees of adequacy the traits, structural characteristics and relations of other objects. This comes to say that in this case, the historical fact of the Armenian Genocide called for an “Azerbaijani genocide of their own” to match Armenians.

The head of the Assistance to Development of Public Relations NGO, Shelale Hasanova in her interview to the Day.az information agency pointed out the mainstays of the Azerbaijani propaganda: “We suffered through four genocides in a single century and we remained unbroken; we survived and we gained independence and we now become integrated into the world community. This is what we must speak and write about not only on the Genocide Memorial Day but during the history classes in schools, at international conferences and during various political actions. I shall remind you these four genocides: the genocide of Azerbaijanis in 1905–1907 in Western Azerbaijan

and in Baku, the genocide of 1918–1920 perpetrated by Dashnaks in Armenia and Azerbaijan, the genocide of 1988 when militant nationalists of the Soviet Armenia banished Azerbaijanis from the lands of Oghuz Turks by torturing and burning them alive. And finally, the forth genocide was perpetrated by Armenian armed bands in Khojaly”.

This anti-Armenian propaganda campaign enlists the assistance of all political and civil institutes. For instance, Elmira Suleymanova, the Azerbaijani Ombudsman, stated that “as a result of a deliberate genocidal policy, ethnic cleansings and deportations perpetrated by Armenians and their supporters against Azerbaijanis over the past two centuries, our people had to endure dreadful ordeals… A total of some 700 thousands of our compatriots were killed”.

There is no need to dwell in detail on every single attempt at falsification of historic events of the region by the Azerbaijani propaganda. It will suffice to focus on the two most circulated examples, that of Guba and Khojaly.

“The genocide of Guba”

In 2007, during drilling works for the renovation of a stadium in Guba, a mass grave of unknown origin was found on the site of a trash dump. Only 35 human skeletons could be lifted to the surface in their entirety. To this day, no result of any archaeological research or expert appraisal on the origin of these remains has been published. Also, no concomitant evidence has been made available.

Meanwhile, on December 30, 2009, the president Ilham Aliyev issued a decree on creation of a “genocide memorial complex” in Guba. Depending on the interests currently at stake, the remains are attributed to Jews or Lezgins or simply Muslims. However, Armenians are invariably cast in the role of the perpetrators.

The text of the decree reads as follows:

At the outset of the past century, as a result of a policy of mass ethnic cleansings and aggression perpetrated by armed bands of Armenian Dashnaks on Azerbaijani lands – in Baku, Guba, Karabakh, Shemakh, Kyurdamir, Salyan, Lankaran and other regions, tens of thousands of innocent Azerbaijanis were killed; one of the most tragic genocidal acts of the 20th century was committed against our people. In April-May 1918, in the Guba uyezd only, 122 villages were completely destroyed. The mass grave in the city of Guba revealed that as a result of the genocide, along Azerbaijanis slain with boundless ferocity and extreme cruelty, thousands of Lezgins, Jews, Tats and representatives of other national minorities were exposed to violence.

What did really happen in Guba? Immediately upon the discovery of the grave in Guba, the speaker of the Azerbaijani parliament Oktay commissioned the director of the History Institute, member of the parliament, Yagub Mahmudov to retain foreign anthropologists and compile an official document “on the mass killing of Azerbaijanis by Armenians at the outset of the past century”. However, foreign experts never showed up in Guba, and the remains discovered there were not given any independent appraisal at least to determine their temporal dimension.

The late president of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Mahmud Kerimov, did not exclude that the remains of Guba might both stem from a mass killing and a mass epidemic.

Meanwhile, Gahraman Agayev, the head of the expedition mounted by the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, stated in relation to the discovery of about 200 skulls: “The researchers concluded that the grave is a result of a genocide perpetrated by Armenians in Guba. A phantom letter by Stepan Shahumyan addressed to Hamazasp which has never been published by the Azerbaijani side is quoted by Agayev as a “compelling” piece of evidence.

Agayev’s claim that the time of the death was accurately established (“The massacre occurred between May 3 and 10”) is equally preposterous. The same can be said about his assertion that “it has been established based on anthropological investigation of skulls that apart from Azerbaijanis, Jews and Lezgins suffered physical extermination in 1918”. Agayev also passed over in silence the revolutionary method that must have been contrived by the Azerbaijani scientists for unraveling the precise ethnicity of the remains.

Yet, his colleague, Maisa Rahimova, the director of the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, seems to be in the same boat as she claims that “anthropological research confirmed that these people were Muslims”

Notice must be taken of the fact that a participant of the same expedition, Asker Aliyev, Candidate of Historical Sciences, clearly states: “Only 35 skeletons could be identified from among a multitude of skulls and children’s bones. No hair, vestiges of clothes or objects were found in the wells”. This means that any assertion about the religious affiliation of the persons, whose remains were found, is not only unprofessional but downright fatuous.

In January 2012, professor Levon Yepiskoposyan, Doctor of Biology, addressed a letter to the president of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, academician Mahmud Kerimov offering to carry out a qualified international expert appraisal of the human remains found in Guba in order to discover scientifically the truth about the mass graves of Guba. In February 2010, the professor came up with another proposal to allow Armenian specialists to take part in a joint anthropological and genetic expert examination of the remains found in Guba; however, his letter remained unanswered.

Meanwhile, Hayk Demoyan, the director of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, notes that there are archive materials proving that the Armenian population of Guba was exposed to violence from the local Tatar bands in 1918, and the number of Armenian victims corresponds to the number of skeletons found at the burial site.

Here is one such testimony. In the late April 1918, Gelovani, the commissar of the city and the region of Guba, sent a telegram to Korganov, the chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee, containing the following: “Today, on April 24, I released 115 Armenians who were jailed in the prison of Guba. They all were divested of their property. I took measures to have their property restituted. They are asking for financial assistance from the Armenian National Counsel. Please, send it to my address as soon as possible. The pecuniary situation is critical… apart from the city of Guba, Armenians are held captive also in other places. I am taking measures towards their liberation”.