По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

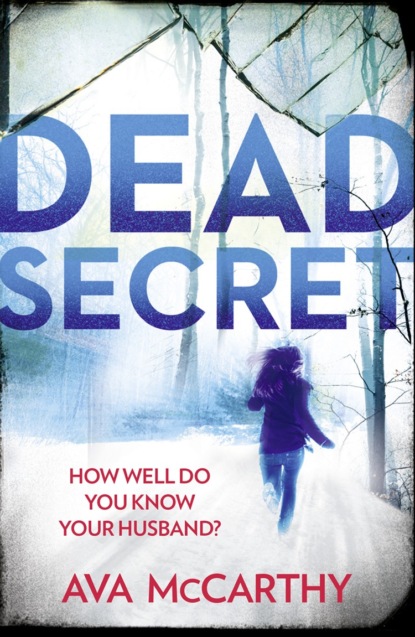

Dead Secret

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The woman had turned and beckoned her in, clattering another sheaf of brushes into the sink. Jodie edged over the threshold. Immediately, the woody scent of turps filled her brain and slammed so many memories into her head it almost sent her reeling.

‘Have a seat. I’m almost done.’

Jodie shook her head, struggling with the reminders of her lost life churned up by the heady smell. Mrs Tate turned off the water and reached for a towel, regarding her with shrewd eyes.

‘I’m sorry to find you in this situation.’

Jodie didn’t answer. The woman went on, still drying her hands.

‘When the papers connected you with Garrett the artist, I didn’t want to believe it. I have one of your paintings on my living room wall.’ She paused, her hands suspended, as she waited for a response. ‘Don’t you want to know which one?’

Jodie managed a shrug. Mrs Tate folded the towel into a regimented square and turned to put it away.

‘It’s the covered bridge on the Contoocook River. All those spellbinding colours. As though it’s drenched in rainbows, I always think.’ She turned back to Jodie, her loose-skinned face pleated into a faint smile. ‘It looks like paradise.’

Jodie recalled the painting, a snow scene caught between freeze and thaw, laced with her signature fantasy colours: chartreuse over lilac, vermilion cut with rose madder. She’d finished it less than two months before she’d killed Ethan.

Mrs Tate must have made the same connection, for she suddenly lowered her gaze. ‘Things are never quite what they seem, are they?’

Jodie shifted her feet. ‘Look, I don’t mean to be rude, but what is it you want?’

Mrs Tate drew herself up, the brisk air restored. ‘I want you to come to the art classes.’

‘Sorry, I’m not interested.’

‘And may I ask why?’

‘Isn’t it obvious? I don’t paint any more.’

‘I don’t care if you paint or not. I want you to teach the other women.’

Jodie frowned, and cast a look around the room: at the pencils, the charcoal, the tinted pastels; at the creamy slabs of paper and cotton-textured canvas. All the materials that had fed her and that she’d shared so much with Abby.

She shook her head, stumbled backwards towards the door. ‘I can’t help you, I’m sorry.’

In the end, it was Dixie who’d talked her into it.

‘Bullshit. Just because you’ve checked out don’t mean you can’t help the rest of us.’ Dixie’s eyes had strayed meaningfully to Nate on the next bunk, whose arms had been freshly scored that morning with self-inflicted welts. ‘It could help some of us get through another day in here, you know?’

Doors slammed outside the art room, and Jodie stole another look at the clock.

3:48 p.m.

Twelve more minutes till the class finished up. After that, she’d be free until the cell count at six. Free to retrieve the hidden stash of pills she’d been stockpiling for the last eighteen months.

Hiding stuff in prison was always tricky. The COs spent their days on the hunt for contraband, ransacking cells, scouring common areas, conducting random body searches. Not to mention the added hindrance of Dixie watching her every move.

Jodie had been forced to switch hidey-holes a couple of times, but so far her stash had been safe. Counting today’s dose, she had thirty-six pills, which by her reckoning had to be enough. Tonight she planned to use them.

‘You okay?’

Momma Ruth’s strong-boned face was turned up towards hers. Jodie nodded.

‘I’m fine.’

The older woman tilted her head, the light catching the broad, olive cheeks that hinted at Cherokee ancestry. Deep lines criss-crossed her skin, like grids for tic-tac-toe. She was fifty-two years old, and had been in prison since she was twenty. She would never leave.

She held Jodie’s gaze. ‘If it’s Magda you’re worried about, she’s in Seg. They frisked her and found the blade.’

‘I heard.’

Seg was the Administrative Segregation Unit, where inmates were isolated in lockdown for disciplinary offences. Most women came out of there a lot meaner than when they went in.

Momma Ruth’s dark eyes still probed hers, and not for the first time Jodie imagined how she might paint her. For the skin, a blend of earthy tones: yellow ochre, cadmium red. For the black hair, layers of ultramarine blue, flecked with titanium white. The challenge would be the eyes; how to capture that taciturn acceptance.

She recalled Momma Ruth’s quiet words of advice the day she got here.

‘Don’t fight it,’ she’d said. ‘I fought it every day for fifteen years, and that just made it worse. Make your peace with it.’ Then she’d held up a finger. ‘But you got to know how to survive. You got to be careful how you walk, how you hold yourself. Always look ahead. Don’t stare at anyone, but don’t look down at your feet. And remember, for some of these women, the more violent it is, the more fun they’re having. You’re dealing with women who don’t care.’

Jodie blinked. She fought the urge to check the clock, and tried to focus on Momma Ruth’s easel.

‘Let’s see what you’ve got here.’

‘It’s not very pretty.’

‘Art’s not about pretty, you know that.’

As usual, Momma Ruth had ignored the plastic mannequin the others were drawing and had painted something abstract of her own. Jodie took in the series of dark, concentric whorls, all rippling outwards across the canvas from a pale blue core.

She glanced at Momma Ruth, then back at the easel, her eyes drawn to the warm blue kernel. ‘You’re not happy with it?’

‘Loops went all sludgy. The browns all look like muck.’

‘What about the blue bit?’

‘Yeah, I like the blue bit.’ Momma Ruth’s eyes flicked to Jodie’s face. ‘Sort of tugs at you, doesn’t it?’

Jodie nodded, studying the pattern of elliptical swirls. ‘It’s important, the blue bit?’

Momma Ruth pushed some paint around her palette with a brush, stirring up the resinous smell of linseed oil. ‘It’s supposed to be … I don’t know. Like, who we are before we make all these bad choices.’

‘You mean innocence?’

‘Sort of. More like a clean slate, you know? Before you make that first bad choice and start up all of these consequences.’ Momma Ruth gestured with the brush at the murky ripples. ‘But the browns aren’t right.’

‘You just mixed too many colours.’ Jodie nodded at the muddy-looking palette. ‘You could fix it when it’s dry.’

‘Make the best of a bad mistake? Maybe.’ Momma Ruth shrugged. ‘Not all bad mistakes can be undone, though, can they?’