По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

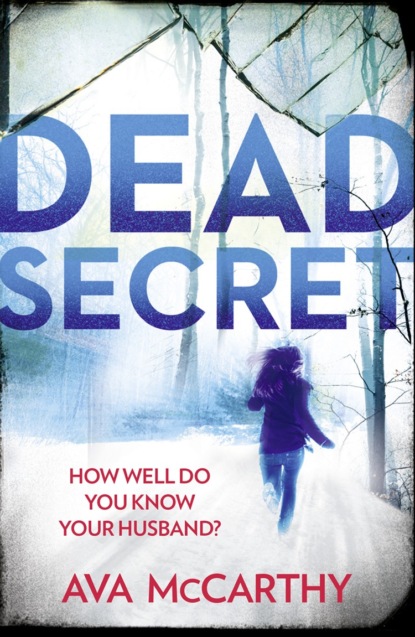

Dead Secret

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Again?’

Jodie kept her tone neutral. ‘Cramps.’

Dixie’s eyes probed hers for a long moment. Then she heaved her apple-round curves up from the table.

‘I’m coming with you.’

The line for medications was already forming, though the infirmary wasn’t yet open. Jodie joined the queue, Dixie by her side, and tried hard not to fidget. A lot would depend on which nurse had pulled duty that week.

Dixie flicked her a look. ‘Hey Picasso, you okay?’

‘Sure.’

Hardly anyone called her Jodie any more. At first, the inmates had called her Cleopatra because of her wide, up-tilted eyes. But when the art teacher learned she could paint and had made her teach a class, the nickname Picasso had stuck.

Dixie’s tone turned casual. ‘Hey, you ever write back to that guy?’

‘What? No, I told you, I’m not interested.’

‘Come on, why not?’

‘I’ve got nothing to say.’

‘What guy?’ Another inmate had joined the queue.

Jodie glanced around. The newcomer was small and wiry, maybe twenty years old, with the buzz cut and swagger of a teenage boy. Her name was Nate, a crack addict from Boston serving four years for aggravated robbery.

Dixie cocked a thumb at Jodie. ‘Reporter wrote to her, wants to do a story.’

‘Awesome!’

‘I’m not meeting him.’

‘Bullshit, you should do it.’ Nate’s angular face lit up. ‘Me, I’d take a visit from anyone on the outside. It’s a distraction, right?’

Dixie nodded. ‘That’s what I said.’

Jodie sighed, bracing herself for another debate on the topic. ‘I told you, he’s just some hack journalist desperate for copy.’

‘But he wants to write a story about you,’ Nate said. ‘How fucking awesome is that?’

‘What story? I killed my husband and they sent me to prison. You think I want to re-live all that with some stranger?’

Nate shrugged. ‘Me, I’d just talk to him. Beats seeing the same old faces in here every day.’ Her dark eyes widened. ‘Hey, maybe he’ll pay you.’

Jodie shook her head. They didn’t get it. Talking about Abby to some journalist was out of the question. And talking about anything else wouldn’t net the guy much either, since trauma had obliterated most of it.

She remembered pulling the trigger, but not much else. They’d told her at the hospital that the car had overturned; that she’d been thrown clear of the wreckage but that Ethan had been found dead at the wheel. They’d been kind at first. Until the police had discovered Ethan had died from a bullet to the head.

The trial had only lasted a couple of weeks. The letter she’d written to the District Attorney had proved without doubt her intent to kill and made it an easy conviction. Her lawyer had tried his best to plead extenuating circumstances, though she’d tuned much of his arguments out, absorbing only snatches.

‘Ethan McCall was a family annihilator. That’s what the criminologists call them. Fathers who kill their own children … ’

‘ … not the first father to decide that a dead child is better than a child he can’t raise himself. That killing his little girl is a fitting way to punish his wife … ’

‘ … monstrous self-obsession … incapable of perceiving his child as a separate human being … ’

‘ … a domineering man … determined to have the final word … to prove he was still in control … ’

‘Grave provocation for my client … unimaginable grief … ’

But in the end, no one had believed that Ethan had murdered his daughter.

Jodie hadn’t fought it. She’d killed him and was prepared to accept the consequences, not planning on being around to endure them for very long.

A lock snicked up ahead. Shutters rattled, and the line of inmates stirred. Jodie craned her neck but couldn’t see who was manning the hatch. Her nails dug into her palms.

Nate nudged her arm. ‘Orianne’s back.’

Jodie followed her gaze to the round-shouldered woman who’d joined the end of the line. Her recently pregnant belly looked slack and deflated. Dixie spoke out of the corner of her mouth.

‘Got back yesterday. Left her baby in the hospital, kissed him goodbye and walked out in shackles. Seven more years to go.’

Jodie stared at the woman’s dull eyes, made blank from the anti-depressants she was most likely on. Her flaccid midsection looked oddly barren.

Jodie looked away. Her own mother had given birth to her while in prison, triggering Jodie’s life on the move in the foster care system. She’d never given much thought to how her mother might have felt at giving her up. Too busy hating her for it.

Her mother had died shortly after giving birth, so when Jodie was old enough, she’d tried to track down her father. His trail had led her from Dublin to Boston, but ended abruptly when she discovered that he was dead too. It was while she was in Boston that she’d first met Ethan McCall.

Nate shifted from foot to foot, shoulders hunched. ‘This fucking line is taking forever.’

The inmates shuffled forward. Jodie glimpsed a white uniform at the dispensary hatch, the face obscured by the women at the head of the line. If Nurse Santos was on duty, she had a chance; if it was Kendrick, she was in trouble.

Dixie threw her an uneasy look. ‘Hey Picasso, let’s go. You don’t need nothing.’

Jodie didn’t answer. Dixie edged closer.

‘Honey, I know you’re stashing them pills.’

Jodie regarded her steadily. ‘You need to stop worrying about me.’

‘Bullshit. We’re family, we look out for each other.’

Family. Ironic that the closest she’d come to having one was in prison. Many of the women here built family structures amongst themselves: mother-figure, father-figure, sisters, brothers. Something most of them never had at home.

Dixie had taken Jodie into her family when she arrived, relegating her to the role of younger sister, though she and Jodie were the same age. Nate was the wayward brother, and there was an uncle called Meatloaf, a two-hundred-pound female wrestler serving ten years for second degree murder. The family unit was presided over by Momma Ruth, a lifer who’d been in prison for almost thirty-two years.

Jodie inched closer to the dispensary, her heart rate picking up.