По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

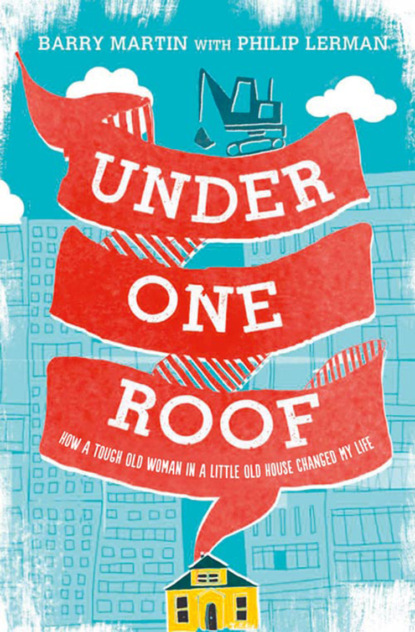

Under One Roof: How a Tough Old Woman in a Little Old House Changed My Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I guess you’re just a little bit bigger than me,” she said.

“Yeah, well, getting a little wider every year, too,” I said.

On the way to the hairdresser’s, Edith and I started talking about how much we liked Ballard. It still says Seattle on the map, but Ballard’s always been a world unto itself. It used to be more of an industrial enclave, although one with a real neighborhood feel; the industry and the residents fit together like a hand and a soft old glove. It had become kind of seedy and run-down over the last couple of years, but it still had the feeling of a community of people who cared about one another. The old Ballard crowd seemed to have known one another for a million years, Edith included. And run-down though the neighborhood might be, they were pretty united against the yuppie paradise that they thought Ballard was becoming, now that the development had begun.

I guess I could see their point, in a way, although I had to admit that the development was helping put food on my table, so I couldn’t complain too much.

We drove under the ramp of the bridge that goes over the ship canal, which connects Puget Sound to Lake Washington. The bridge itself connects Ballard to Seattle proper, and it’s central to everything that happened. At some point, people started realizing what a great place this would be to live – right on the water and, thanks to that bridge, such an easy commute to downtown. Only the folks who already lived here didn’t see it that way. They saw this all as an invasion. Edith and I were driving past a few of the new condos that were going up, the ones that all the Old Ballard folks were all upset about.

For a while, the condos were popping up like popcorn. At one point, in fact, they put a moratorium on residential construction and set aside five thousand acres for industrial use, because all of the industry was getting pushed out and everybody was up in arms about losing the heart and soul of Old Ballard. Most of the condos that had gone up so far were actually a little ways to the south, and I was surprised, at first, that the developers were putting up a shopping mall here on Edith’s block, because I didn’t think there were enough people to warrant it. But when I heard about all the new condos that were planned, the project seemed more like a no-brainer.

On the opposite side of the canal was the spot where they park the boats for the TV show Deadliest Catch. You couldn’t quite see it from where we were driving, but I’d passed it earlier and seen a tour group forming on the dock. I mentioned it to Edith, and commented on how much Ballard had changed since the last time I’d been here, which had been a while ago. I’d come down to go to the locks and walk around, and there was a construction supply place I used to go to every once in a while. We were just down the road from that place now. I asked Edith if all of the change that was coming to Ballard bothered her the way it did some people.

“No, it doesn’t really matter,” Edith said. “Change is change. You know, that building you’re going to build, twenty years from now they’ll tear that down, too. They tore down the Kingdome, just twenty-five years after they built it, you know. They still owed twenty million dollars on it. That’s just progress, Barry. That’s just how things go.”

“Well, that’s pretty philosophical of you, Edith,” I said.

“Not philosophical at all,” she said. “Realistic. World of difference between the two. Things are what they are.”

I wondered what it was in her life that made her so accepting of change, and at the same time so stubborn about it when she wanted to be.

As we drove, I mentioned that I heard they were thinking of tearing down the Denny’s that had been a fixture in the town since the sixties. I’d been driving past that Denny’s every morning on my way to work.

“Well, the plans are all messed up,” Edith said. “Some folks are trying to get historical status for it. You know those big, sweeping beams it has in the front? Some famous architect from Seattle designed it.”

“Can’t believe they’re going to take it down,” I said.

“I don’t know why everyone was so up in arms,” Edith said. “Historical status for a Denny’s? It’s ridiculous. Change is change,” she said again. “It happens. You need to learn to live with it.”

Maybe so. But as we turned right up toward Market Street – the first time I’d been over there since before we started the project – I was kind of shocked at how different it was. Not the buildings themselves, but the businesses in them. I could almost see what all the fuss was about. We passed a fancy tea shop, a place that sold high-end stereo equipment, and some very nicely dressed folks wearing expensive sunglasses were drinking coffee outside the India Bistro. Dads and kids with bicycles that had shock absorbers in the front were riding past Shakti Vinyasa Yoga across the street.

“It sure is different,” I said. “I still like it, though. I’ve always liked how everything’s so close together in Ballard.”

“You can get from anywhere to anywhere in about five minutes,” she said, and as if to prove it, she added, “Here we are.”

It had, indeed, taken all of five minutes to get from Edith’s out-of-the-way house to the hair salon in the middle of Market Street.

Everybody in the salon knew Edith, and she seemed to know everybody. She greeted each of them by name. If anyone seemed surprised to see Edith with an escort, they didn’t say, and she didn’t offer any explanation. She just asked them how long they thought she’d be there, and they told her about forty minutes. She asked me where I was going to go.

“Well, everything’s about four minutes from here, Edith, so wherever I am, you all give me a call when you’re five minutes from being done and I’ll be here.” I handed my card to the woman who ran the shop.

“Well, all right then,” Edith said, and tilted her head to regard me with a clear, direct look. “Thank you, Barry.”

It was a little early for lunch, but as long as I was on Market Street, I figured I’d continue down to the Totem House. That’s one of the places that had been there a long time. It has a big, corny totem pole out front, and they sell a great seafood chowder. I picked up an order, and decided to drive down toward the beachfront.

A train was passing over the railroad trestle about a quarter-mile down the road. Just beyond that were the locks; by the flow of the water, it looked to me like they had just been opened. It’s kind of amazing, when you think about it – down here, just west of downtown, is salt water. It’s actually the other end of the canal from Edith’s house, just five minutes away, and that’s fresh water. The locks are what connects them. If they just opened the locks, I figured, a boat should be showing up here pretty quick. I like the locks – they have a viewing window down there, and when the salmon are running you can go in and watch them.

I drove past the marina, past the hundreds and hundreds of sailboats – that’s one thing about Ballard that hasn’t changed: They do love their boats. Just beyond the marina, there were a good hundred people sitting on benches and lying on blankets all over the beach. Nobody was in bathing suits, because it was still too cold, and besides, the water’s about 54 degrees that early in the season, but a beach day is a beach day and everybody was out there with picnic lunches, only no bathing suits. Shirts and pants and beach balls. Kind of a funny scene.

It was just a few minutes after I got back to the trailer that my cell phone rang. Edith was ready to go home, so I jumped back in her car. She was waiting for me at the door of the salon; as I helped her back into the car, I got a big whiff of hairspray, one of those things that just transports you into another time, another era. I guess my mom must have used that kind of hairspray, or something, when I was a kid. It occurred to me that with everything else going on that morning, I hadn’t really taken a moment to consider that here’s this woman, well into her eighties, living a pretty solitary existence, and still going to the trouble of getting her hair done on a regular basis. It says something about her, and about her generation, I guess. For some reason I remembered those pictures you see of men at baseball games, years ago, in shirts and ties and fedoras. There was something a little more proper and formal about the way they went around in the world; it seemed like a measure of respect for each other, and for themselves, I guess, that’s kinda been lost as time goes by.

When we got back to the house, I walked her to the front door. I still had never been inside the house, and I was kind of curious about how she lived in there, all alone all these years, but I wasn’t going to find out this day.

She turned and smiled. “Thank you again, Barry. That was very neighborly of you.”

“Not a problem. Let me know if you need anything else. Say, Edith?”

“Yes, Barry?”

“Your hair looks real nice.”

Over the course of the next few weeks, I had more visits with Edith, always in the front yard. But one morning, she wasn’t out where I expected to find her, so I knocked on her door, and she called from the kitchen for me to come in.

I will never forget that moment I stepped inside. Never. The first thing I saw was the end table. It was the table from my childhood. It was that classic fifties style – a plastic-laminate end table, dyed light tan to look like wood, small and rectangular, with a second shelf, half the size of the lower table, raised above it on two thin wooden side slats. On the higher shelf sat a lamp, and when I saw it I about fainted right then and there. Not only was the table the same, but this was the same exact lamp my family had when I was a kid as well. Same color and everything. It had a pink ceramic base shaped like an inverted vase, with little gold rods protruding from its top, and little gold metal balls on the ends of them. It was topped off with a wide translucent yellow paper shade, rimmed with a spiral metal edging and decorated with little brown palm fronds.

Looking at that table and lamp, this whooshing sensation came over me, like I was being transported back in time. And I was, really. For a second there, I was a kid again, walking into my mother’s house, half expecting to get offered a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or get hollered at for not wiping my feet.

When I got my bearings back, I took a moment to look around. I couldn’t believe how much stuff there was – all the books and records and CDs and figurines and photos – but still how very neat and tidy it all looked. Everything in its place.

The sun glinted off a metallic etching that was hanging on the wall. There were four of them, not quite gold, not quite silver; all street scenes from Venice. I wondered what the story was behind those.

When Edith came back into the room, I asked her about the etchings, but all she said was, “It’s an interesting story. I’ll have to tell you about it sometime.” A very polite way, I guess, of saying “None of your business.” So we moved on to other topics. She told me her friend Gail had stopped by earlier that day. Turns out Gail was just a kid growing up on the block when Edith first met her. In fact, Edith used to babysit for Gail and her sisters a lot. Gail had gone off to Alaska for a long time but came back a few years ago and now stopped by every now and then, and brought pictures of her and her sisters, all grown up now, and all of their children, all grown up as well.

It was nice to hear that her friend was still coming by after all these years, and, frankly, that Edith had some company besides me.

When I got back to the trailer I was surprised to see how late it had gotten. I’d wasted a good part of the morning with Edith, yakking about everything and nothing. I was finding it easier and easier to talk with her. Driving home that night, I thought about why that might be. What was it that was drawing me to her? You know how your kids spend an overnight at someone’s house, and they come home, and the parents tell you how well-behaved and polite and helpful your kids were, and you think, “Are you talking about my kids?” There’s something about kids, I guess, after a certain age, that they can relate to other people better than they can to their own parents. Maybe you’re too close, or maybe it’s their need to rebel, or something. Well, it never occurred to me that the same thing could still happen to you when you’re all grown up. Somehow, I was already finding it easier to have conversations with Edith than I ever had with my own mom or dad. I guess there were two reasons for that. For one thing, I felt like Edith didn’t take things personally the way my own folks would. I guess that’s just natural. Same with my own kids – no matter what they tell you, you can’t help flashing back on things you’ve done and wondering if whatever problems they have are your fault in some way. But it was more than that. I also started realizing how much alike we were. Edith didn’t sugarcoat things. She told you right out what she felt. I’m not so different. I see things pretty much in black and white. If something’s not right, it’s wrong. People can do what they should do, or they can not do it, but there usually isn’t much question about what the right thing is. I felt really connected to Edith because, it seemed, she felt the same way. A little later, she would tell me stories of how she took in all these war orphans in England, and when I heard them I thought, What makes a person do something like that? But for her, it was simple: You do what has to be done.

I think I’m a lot like that. I hope I am, anyway. You do what needs to be done and you don’t worry much about why or how you feel about it. You just do it. I think that’s why it was so easy for us to talk. We shared something deep and true: an assumption about how you live your life.

Of course, it wasn’t always easy to talk to Edith. One afternoon I saw these two guys coming down the street. They were quite a sight – both of them in their sixties, but still trying to be hip. Or some circa-1970 version of hip. One of them had a jacket and slacks and tie that looked like they came from three different secondhand stores. The other had gray hair and little round John Lennon glasses, like a refugee from a Woodstock reunion. To top it all off they were struggling along with a big hulking old video camera, and I guess they were going to interview Edith. Or thought they were, anyway. I figured it was about the same thing everybody always wanted to talk to her about – how she was standing up to the horrible developers and all that guff – but when I introduced myself to them and asked them what they were up to, I was surprised by the answer.

“Well, you know she used to be a spy,” the guy with the glasses said, as matter-of-factly as if they said she used to be a telephone operator.

“Well, no, I didn’t know that,” I said. “Did she tell you that?”

“She sure did, man,” he said. “And we have confirmed it through independent research.”

Now, to be honest, these guys didn’t seem to me like they had both oars in the water, so I didn’t put much credence in what they were telling me. I left them to their business and went about mine. Later that afternoon, when I went over to chat with Edith in her front yard – I don’t know if she’d ever talked to the guys or not, but they were gone now – I came right out and asked her about it.

And she came right out and told me to go to hell.

“Mind your own business!” she said. She was pulling some weeds and didn’t even bother to look up. “Why the hell people dwell in the past is beyond me.”

I thought, well, okay, I guess we won’t go there today.

I was still thinking about Edith when I drove up to see my parents that weekend. I usually go up every couple of weeks. It’s a pretty nice drive, once you get over the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which is about halfway to their house. After that the roads get smooth and winding, following a serpentine route along the Hood Canal. You can see the canal and the Olympic Mountains behind them, and I don’t think I’ve ever taken the drive without stopping to take a picture, of the fog rising up, or snow on the high peaks, or the clouds piling up and rolling over the mountains. Or the beaches, all covered with sun-bleached oyster shells. Every time it’s a different view.

The traffic was light, so I pulled up to their place in a little over two hours. Their house is in the woods, on the thirteenth green of the Alderbrook golf course. Not a lot of manicured lawns up around there – there’s too much rain. The biggest crop up here is moss.