По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

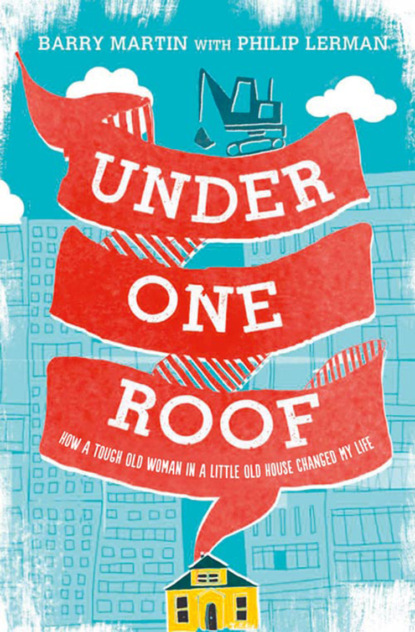

Under One Roof: How a Tough Old Woman in a Little Old House Changed My Life

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I’m not sure if being with Edith made me want to see them more. When you spend time with someone who’s a good fifteen years older than your parents, you start imagining them getting old, and I guess you start feeling guilty for not spending more time with them. Maybe it was that, or maybe it was the way my dad had been changing recently that made me feel like I really wanted to go see them more often. Mom and Dad both used to golf a lot, but lately Dad was going less and less. There were other changes as well: he had given up bridge altogether, for example. He’d make excuses about why he was quitting that stuff; they didn’t ring true, but you didn’t want to press him. I mean, if he doesn’t want to talk about it then he doesn’t want to talk about it – but you’d still walk away feeling kind of puzzled and confused.

It probably wasn’t the best day to spend together. My dad and mom were bickering all day – or to be honest, my dad was doing most of the bickering. I don’t know why, but he was picking on my mom over the strangest little things, like the milk wasn’t where it was supposed to be in the refrigerator. Or she’d left the clean laundry in the laundry basket instead of putting it away.

Late that afternoon we sat down in the family room, and I looked out the sliding windows at the thirteenth green. It was vacant right at the moment. Dad stretched back in his leather recliner and started telling me a story about the time he was eighteen and went on a NOAA ship to Alaska, to map the bottom of the ocean, at about the time a volcano was erupting there. Only, he couldn’t think of the word volcano. Suddenly, he started acting angry at me: “Randy, what do you call that thing, for chrissakes?”

I don’t know what freaked me out more: the fact that he was cursing (because he never cursed), the fact that he called me by my brother’s name instead of my own, or the fact that he couldn’t think of a simple word. It was scary, but I just let it go. “A volcano, Dad,” I said. “Right. A volcano,” he responded. “Well, you can imagine how excited I was. Eighteen years old and headed for Alaska! What an adventure.”

As I listened to him spin the tale, my mother came in with a couple of cold glasses of water. As she bent over to put one on the little table next to Dad’s chair, she paused, for just a second, and gave me a look, as though she was trying to tell me something. When I drove home that night, I remembered that look. I wondered what she was worrying about, and whether it was the same thing I was worrying about, too.

Lately, I’d been kind of impatient with my dad. I was just miffed at him. I couldn’t put my finger on why exactly, but as I’d started the project in Ballard, I’d been getting more and more calls from my mom about him. Little things, mostly – the things couples argue about when they’ve been together, like my parents had, for more than fifty years – but it seemed like in the last few months there’d been more arguments than usual, and they’d gotten a little more serious. She noticed that he was flying off the handle more, over nothing, like I’d noticed when I’d been at their house. I’d tell him a story, and he’d mention it a little later, and my mom would correct him because he’d get the story mixed up, and out of nowhere he’d start yelling at her. It would just last a second, and normally you wouldn’t think anything of it, but it was a little different from the way he usually was. My dad was the kind of guy who was always in control of everything.

I wouldn’t show him that I was miffed, of course. I was raised to respect my elders, and that carried through to when I was an adult. I always did what he told me. I didn’t always like it, but I didn’t talk back. It’s just the way we were raised. So even if I was getting pissed off now and again, I didn’t say anything to him about it.

I don’t think any of us is prepared for our parents to start to decline. I know I sure wasn’t. It’s denial, I guess. It’s not that I didn’t know what was happening to my dad. It was that I didn’t want to know.

It was about six weeks after I took Edith to her first hair appointment that she asked me to take her again. I went over early that afternoon, and from the moment she entered the living room, I could tell that she was loaded for bear.

“I just want you to know I didn’t appreciate that call this morning,” she said, her voice full of venom. “You boys just keep hounding me to move, don’t you? Well, I’m not moving, so you might as well stop bothering. Save your breath!”

I had no idea what she was talking about.

“Your friend over there at the company,” she said. She was bundled up in a big brown sweater, and in her anger she seemed more hunched over than usual, like she was a snake all coiled up and ready to spring. “He tried to sound all polite. But I know what he’s up to. I know what you’re all up to. Forget it! I’m not moving. Why should I!”

Now, I’d been nothing but a perfect gentleman to Edith since I met her, but for the first time, I started to get angry. I know a lot of people saw Edith as a symbol of someone standing up for what’s pure and true, or something like that. But that’s not my battle, I thought. Don’t make me the bad guy.

I’d been polite, and helped her out, and was taking her to her hair appointments and whatnot, and now I felt a little – betrayed, I guess.

“Listen up,” I said. I was kind of surprised at how loud my voice was, but you know how it is: once you’re on a roll, it’s hard to stop. “None of this makes any difference to me. I work by the hour. If you stay or if you go, there’s no benefit to me one way or the other. The job is the same number of hours either way. I build to the property line all the way around, no matter what that property line is. So don’t put me in that.”

I felt bad as soon as I let all that out. I mean, what am I doing, going off on some eighty-four-year-old woman? But Edith seemed almost relaxed by what I’d said. She moved forward, from the shadows in the corner, into the beam of light, flecked with dust, that streamed through the window. “All right then,” she said. “Well, I apologize for that. I understand your position. I suppose we should get going now, shall we?” She seemed very calm. I guess she was trying to figure out just how far she could push me, and now that she knew where that line was, she could work from there. It was like we were both pushing right up to the property line. We just had to know what the boundaries were.

We went out to the car, and started up past the bridge. The sun was reflecting off the canal, and I put down the visor. A few fishermen passed in front of us at the stop sign near the Salmon Bay Café. That café’s been there a long time but seemed a lot busier than I remembered it. There was a little traffic jam of people getting into the parking lot for lunch.

I felt like Edith and I had crossed a certain barrier that morning. By letting out our anger over the subject, we made it a little easier to talk about. So as I swung the car onto Market Street, I broached the subject again.

“Now, you know that I don’t care one way or the other if you move, right?”

“Yes, I understand that,” she said.

“Well, then, can I ask you a question?”

“Sure, sure,” she responded.

“Why don’t you want to move?”

She looked out the window.

“Why should I move?” she said, that crotchety tone creeping back into her voice. “Where on Earth would I go? I don’t have any family. There isn’t anywhere for me. This is my home.”

“So it’s not what people think, is it?”

She turned toward me. “It’s never what people think.”

I figured that was the end of it. But later that morning, after I brought her back from the hairdresser’s, she opened up to me one more time.

I’d walked her back into the house just to make sure she’d gotten settled okay, reached down to turn on the lamp on the little side table, and was getting ready to go back to work. Edith was sitting on the couch and looked up at me. She seemed smaller, somehow; curled up quietly on the couch, not hunched or coiled like before.

“Barry, I want to tell you something,” she said, her voice cracking a little bit.

I just turned, and was silent.

“My mother died right here, right on this couch,” she said. The tears were starting to form again. “I came back to America to take care of my mother, and she always said she wanted to die at home, not in some – facility – and she made me promise, and I promised her. She died right here, Barry. And this is where I want to die. Right in my own home, on this couch. I’m not asking you to promise me, but I want you to know. Everybody wants me to move, and they all think it’s best for me. But I know what I need. I need to be right here. This is my home. I want to live here and I want to die here. Do you understand?”

I looked down at this woman in the soft light filtering in through the thin curtains. She seemed so frail and so strong, at the same time. So vulnerable and so impenetrable. So needy, and yet so fiercely independent. I was moved by what she’d told me, and felt strangely protective of her. It was such a simple request, and it seemed so wrong that she should have to even fight for it. Even a Death Row prisoner gets to choose his last meal.

“I think I understand,” I said. “Thanks for telling me that.”

“Well, thank you for listening.” She looked down, then back up at me. “Thank you for everything, Barry. You know what you are? You are a true human being.”

I didn’t know exactly what she meant by that, but I figured it was a good thing.

“Thanks, Edith. See you tomorrow.”

“Yes. I’ll see you tomorrow. Tell your wife I said hello. I’d love to meet her sometime.”

And that was that. I felt, again, like we’d crossed some kind of border, into some new territory. It felt a little frightening and intriguing all at the same time, but more than that, it felt like we had become closer, part of each other’s life in a way we hadn’t been just a few minutes before.

I closed her door quietly and headed back to the construction trailer, trying to clear my mind, to focus on the tasks at hand. Feeling a little guilty for taking so much time off work that morning, but feeling pretty okay about it at the same time, for all that had occurred.

4 (#u0df9ce84-d574-5d85-89f3-ddb3f6a2b4ec)

I was surprised by how self-sufficient Edith seemed in those first few months. She wasn’t, however, getting by all on her own. A friend of hers, a fellow named Charlie, was coming by pretty regularly. Charlie looked like an unmade bed. Tall and wiry with long gray hair, he was younger than Edith but older than me, probably in his early sixties. He had that leftover-hippie kind of look. I’m not sure how they got to be friends, but they seemed to have that Old Ballard connection, and it went back a long ways. He did her shopping and helped around the house, although he didn’t seem to stick around much once the chores were done. He said he was a project manager on construction sites, although when I tried to talk shop with him he’d change the subject. Still, he was helping Edith out, so I figured he was an okay guy.

Charlie’s the one who first told me about the social workers, one morning in the late summer. “They’re hovering again,” he told me. Charlie had that way about him – he’d start up in the middle of a conversation, as though you’d already been talking and knew what he was talking about. It took a minute to catch up.

“Morning, Charlie. Who’s hovering?” I asked him.

“Social workers. They’re back at it again. If they think they’re going to get her to move, they’ve got another think coming.”

It took a while to get Charlie to tell the story in some kind of order I could understand, but once I got all the pieces of it, it made sense. The state had been after Edith for some time, concerned that she was not competent to take care of herself. They couldn’t make her move – they couldn’t prove that she was a danger to herself or anything – but they were apparently putting on a pretty strong push. Charlie said they kept coming around again and again, being persistent about how much better off she’d be, how much more comfortable she’d be, how much better her life would be, if only she’d let them bring her to a facility. I remembered how she used that word – facility – when she told me about her mother, how much disdain she had in her voice. It made me wince just hearing Charlie say it.

Now it made more sense to me why Edith was so touchy when guys from my office kept offering her more money to move. She must have felt she was battling on two fronts just to stay in her house – with the Bridge Group coming at her straight on and the social workers from the flank. I’m sure that, to Edith’s ears, what they were both saying was, “You’re not able to take care of yourself anymore. Let us do it for you.”

I don’t think anybody wants to hear that they can’t take care of themselves. Certainly not a tough old bird like Edith.

Charlie took off, and I knocked on Edith’s door. I wanted to ask her about the social workers, but when she called me to come in, I found her at a rickety little desk in the corner of the living room, typing at – well, I’m not sure what you call it anymore. It looked like a cross between a late-model electric typewriter and an early PC. The thing must have been twenty-five years old. It had a tiny square computer monitor and a dark gray keyboard with white keys – not like a modern keyboard, more like a typewriter – and she was pecking away at it, slowly. I saw the word Whisperwriter on it.

“Good morning, Barry,” she said. “Excuse me for just a moment. My fingers don’t work quite as well as they used to.”