По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

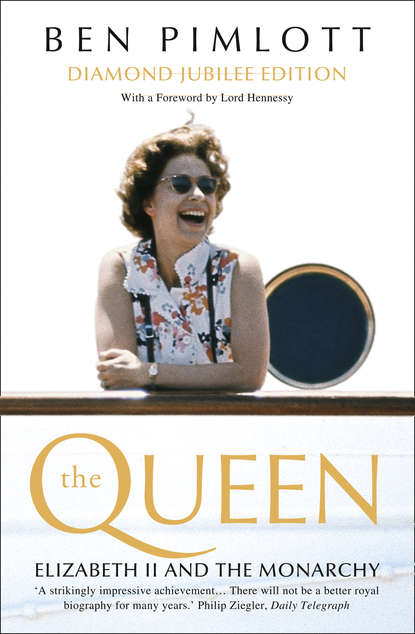

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Perhaps she had Philip’s recent dangers and exploits, and those of his royal house, partly in mind.

Such an officer was likely to be rapidly promoted in wartime, especially if he had ambition. In Philip’s case, the energy and drive he had shown at Gordonstoun and Dartmouth, together with a view of his own long-term future which received ample encouragement from his Uncle Dickie, helped to push him forward. Mike Parker, a fellow officer who had also been a fellow cadet and later became his equerry, recalls thinking of the Prince as a dedicated professional and as a man heading for the very top: somebody who already ‘had mapped out a course to which he was going to stick . . . a plan already in his mind that had probably been set before he left’.

In October 1942, Philip was made First Lieutenant and second-in-command of a destroyer, at twenty-one one of the youngest officers to hold such a post.

His adventures continued. The following July, while courtiers in Buckingham Palace exchanged learned memoranda about the date of Princess Elizabeth’s coming-of-age and its constitutional significance, Prince Philip was aboard HMS Wallace off the coast of Sicily, helping to provide cover for the Allied attack and possibly bombarding one of his brothers-in-law, on the German side, in the process. In July 1944, his ship was sent to the Pacific, where he remained until after the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and until the final surrender of Japan.

Wherein I spake of most disastrous chances,

Of moving accidents by flood and field,

Of hair-breadth ’scapes, i’ the imminent deadly breach . . .

My story being done,

She gave me for my pains a world of sighs.

It is hard to think of an experience of war further removed than that of the Heiress Presumptive, in her castellated schoolroom.

At first, Philip’s busy war provided little scope for contact with the British Royal Family. Shore leaves were brief, makeshift and hectic. Parker felt that it was a bond between him and Prince Philip that both of them were ‘orphans’ (Parker was Australian), with a problem about where to stay.

In London, Philip was often put up by the Mountbattens, who had been bombed out of previous homes and were living in a house in Chester Street. Mountbatten’s younger daughter Pamela recalls that she and a camp bed would move from room to room to provide space for her cousin, who would ‘come and go and added glamour and sparkle to every occasion’.

His favours were distributed widely. Queen Alexandra, herself in London at the time, maintained that ‘the fascination of Philip had spread like influenza, I knew, through a whole string of girls’.

But there was no special girlfriend. According to Parker, ‘never once did I ever find him involved with any particular one. It was very much in a crowd formation’.

Other stories about Philip in wartime confirm the impression of a hedonistic, though also cashless, socialite whose uniform, looks, charm and connections opened every door – a character out of Evelyn Waugh or Olivia Manning, who popped up wherever in the world there were enough members of the pre-war upper class to hold a party.

Princess Elizabeth was sometimes in his thoughts. Alexandra met up with him in 1941 in Cape Town, where he was on leave from a troop ship. When she came across him writing a letter, he told her it was to ‘Lilibet’. Alexandra assumed – such were the mental processes of displaced royalty – that he was fishing for invitations.

Perhaps she was right. It was not, however, until the end of 1943 that he was able to accept one of importance. This was to spend Christmas with the Royal Family at Windsor Castle, and to attend the annual Windsor family pantomime.

Philip accepted, with pleasure.

It was a private invitation. However, both the show, and the Prince’s attendance at it, were reported in the press. In November, it was announced that a stage had been erected in a large hall in the ‘country mansion’ where the princesses were staying; that a cast of forty was rehearsing under the joint direction of Princess Elizabeth and a local schoolmaster, who had together written the script; and that twenty-five village school children would provide the chorus, accompanied by a Guards band.

A few days before Christmas, The Times reported that ‘Prince Philip of Greece’ had attended the third of three performances, sitting in the front row. Others in the audience included the King and Queen, various courtiers, royal relatives, and villagers.

According to Lisa Sheridan, Prince Philip was more than just a passive spectator of the seventeen-year-old Elizabeth as she acted, joked, tap-danced and sang a few songs just in front of him. ‘Both in the audience and in the wings he thoroughly entered into the fun, and was welcomed by the princesses as a delightful boy cousin.’

The pantomime was followed by Christmas festivities. On Boxing Day, there was a family meal at the Castle including retainers, Prince Philip and the young Marquess of Milford Haven. ‘After dinner, and some charades,’ Sir Alan Lascelles recorded in his diary, ‘they rolled back the carpet in the crimson drawing-room, turned on the gramophone, and frisked and capered away till near 1 a.m.’

Crawfie maintained it was a turning point: thereafter, Elizabeth took a growing interest in Philip’s activities and whereabouts, and exchanged letters with him. The Heiress to the throne enjoyed the idea of being like other girls, she suggested, with a young man in the services to write to.

IF ELIZABETH only began to think seriously about Philip in December 1943, she was way behind the drifting circuit of European royalty and its hangers on, which had been talking about the supposed relationship, almost as if a marriage was a fait accompli, for two or three years. Of course, Philip’s eligibility as a bachelor prince, together with his semi-Britishness, was likely to make him the subject of conjecture in any case. However, before the end of 1943, the couple had little opportunity to get to know each other. What is curious, therefore, is the firmness of the predictions, and the confidence of the rumours, from quite early in the war.

One of the first to pick up and record the story of an intended marriage, in its definite form, was Chips Channon, befriender of Balkan princelings. He heard it at the beginning of 1941 during a visit to Athens, where the tale seemed to be current among the Greek Royal Family, whose interest had been sharpened by the presence of Prince Philip in their midst, on leave from his ship. After meeting Philip at a cocktail party, Channon noted in his diary, ‘He is to be our Prince Consort, and that is why he is serving in our Navy.’ The alliance between the British and Greek royal houses had supposedly been arranged by the finessing hand of Philip’s uncle, Lord Mountbatten. Philip was handsome and charming, noted Channon, ‘but I deplore such a marriage. He and Princess Elizabeth are too interrelated.’

Such an item was, of course, no more than gossip, a symptom of the decadence and anxieties of the Greek court. Princess Elizabeth was fourteen at the time, and the notion of the British Government or Royal Family fixing a future marriage alliance with the Greek one is preposterous. According to Mountbatten a few years later, it was at about this time that Philip ‘made up his mind and asked me to apply for [British] naturalisation for him’.

Perhaps it was news of this plan, combined with Philip’s evident closeness to his British uncle, that inspired the tale. Nevertheless, the existence of such a lively and, as it turned out accurate, rumour nearly three years before a serious friendship is supposed to have started, puts the Prince’s visit to witness the Princess performing into perspective. Had Mountbatten been involved behind the scenes? It is possible. ‘He was a shrewd operator and intriguer, always going round corners, never straight at it,’ says one former courtier from the 1940s, ‘he was ruthless in his approach to the royals.’

Another suggests: ‘Dickie seems to have planned it in his own mind, but it was not an arranged marriage.’

It would certainly have been in character for him to have followed up on the 1939 introduction. That, however, is a matter for speculation. What is clear is that in the course of 1944, despite the huge pressures on him, Lord Mountbatten took it upon himself to follow through his match-making initiative with operational resolve.

One effect of the Christmas 1943 get-together, and of its publication in the press, was to fuel the rumours. Prince Philip himself was reticent. Parker knew that Philip had begun to visit the Royal Family when he was in England, but he did not find out the significance of the visits until after the war.

Others had more sensitive antennae. In February 1944, Channon again got the story, this time from a source very close to the throne – his own parents-in-law, Lord and Lady Iveagh, who had just taken tea with the King and Queen. The Windsor party had evidently been a success. ‘I do believe,’ Channon reaffirmed, ‘that a marriage may well be arranged one day between Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip of Greece.’

Meanwhile, in Egypt, where the Greek royal family presided over the Government-in-exile, interest had deepened, and with good reason. Within months, or possibly a few weeks, of the Windsor meeting, Philip had declared his intentions to the Greek king. The diary of Sir Alan Lascelles contains a significant entry for 2 April 1944 in which he records that George VI had told him that Prince Philip of Greece had recently asked his uncle, George of Greece, whether he thought he could be considered as a suitor for the hand of Princess Elizabeth. The proposition had been rejected.

However, it was early days.

In August 1944, the British ambassador, Sir Miles Lampson, recorded meeting Prince Philip, once again on leave, at a ball in Alexandria, in the company of the Greek crown prince and princess. Lampson found him ‘a most attractive youth’. In the course of the evening, the crown princess let slip ‘that Philip would do very well for Princess Elizabeth!’ an idea now of long-standing, and one on which the beleaguered Greek royal family was evidently pinning high hopes.

Philip’s presence in Egypt, however, inspired more than a minor indiscretion from a relative. On 23 August, according to Lampson, Lord Mountbatten, now Supreme Allied Commander in South East Asia, arrived in Cairo by air and proceeded to unfold a most extraordinary cloak-and-dagger tale. The purpose of his mission, Mountbatten explained as they drove to the embassy from the aerodrome, was to arrange for Prince Philip, ‘being a very promising officer in the British Navy,’ to apply for British nationality. Gravely, Mountbatten explained that King George VI had become concerned about the depleted numbers of his close relatives, and believed that, if Philip became properly British, ‘he should be an additional asset to the British Royal Family and a great help to them in carrying out their royal functions’. It was therefore his intention, he continued, to sound out Philip, and then the king of Greece, about his proposition. In the course of the same day, both were sounded, together with the crown prince, and all three agreed. Early that afternoon, a satisfied Mountbatten left by aeroplane for Karachi to resume his Command.

What should we make of this very curious account? Mountbatten’s explanation for his ‘soundings’ is obviously unconvincing – the one thing the British Monarchy did not need was functional help from a young foreign royal, let alone a Greek one, just because he happened to be on the market. The only way that Philip could be ‘an additional asset’ to the Windsors was by marrying into them, and this, as Lascelles’s note the previous April shows, he by now wished to do. It seems much more likely that Mountbatten’s mission was part of a considered plan, aimed at remoulding Philip for the requirements of the position both uncle and nephew wished him to hold. To make such an objective obtainable, Philip needed to be, not so much British, but non-Greek, in view of the unsavoury connections of his own dynasty. In short, the Egyptian whistle-stop visit was an opening move. Such an explanation is consistent with the behaviour of Lord Mountbatten over the next two or three years, as he bent ears and pulled strings in Buckingham Palace, Westminster and Whitehall, at every opportunity. So great, indeed, was Mountbatten’s determination on his nephew’s behalf, that at one point Prince Philip was moved to chide him gently for almost forcing him ‘to do the wooing by proxy’.

The wooing proceeded apace. There were meetings between Philip and Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace, and also at Coppins, the home of the Kents, as the ubiquitous Channon discovered when he inspected the visitors’ book there in October 1944.

The problem from the start was not the Prince’s courtship, but the British Government, concerned about its wartime Balkan diplomacy, and the hesitation of the Princess’s parents. Despite Mountbatten’s bold claim to Lampson in August that the British King was behind the naturalization initiative, nearly six months elapsed before Buckingham Palace made even tentative inquiries at the Home Office on Philip’s behalf. ‘The King asked me recently what steps would have to be taken to enable Prince Philip of Greece (Louis Mountbatten’s nephew) to become a British subject,’ Sir Alan Lascelles wrote to the relevant official in March 1945. The King, he explained, did not want the matter dealt with officially yet: he only wished to know ‘how it could be most easily and expeditiously handled’ at an appropriate time.

In August, Lascelles went to see the Permanent Secretary at the Home Office, at the King’s behest, observing crustily, ‘I suspect there may be a matrimonial nigger in the woodpile.’

The question of Philip’s naturalization, however, only became a matter for political discussion at the highest level in October 1945, by which time Greek politics, and the Greek royal family’s embroilment, had become even more tangled. The Prime Minister, Foreign Secretary and Home Secretary now considered the proposal put to them by the Palace but, faced with the prospect of stirring a hornet’s nest, postponed a decision. The danger, it was explained to the King, was that such a step would be interpreted in Greece as support for the Greek royalists. Alternatively, given the feverish nature of politics in the Balkan peninsula, it might be taken ‘as a sign that the future prospects of the Greek Monarchy are admitted to be dark,’ and that Greek royals were scurrying for safety abroad. In view of these competing risks, Attlee suggested that the question should be left until after elections and a plebiscite had been held in Greece the following year.

When Prince Philip returned from the Far East early in 1946, the problem acquired a new urgency. Philip’s undemanding peacetime job, as a member of staff of a naval training establishment in North Wales, provided ample opportunity for frequent visits to Buckingham Palace, where his charm worked, not only on Princess Elizabeth, but on Crawfie, who found him a breath of fresh air in the stuffy Court, ‘a forthright and completely natural young man, given to say what he thought’. Above all, he could talk to Elizabeth as no outsider had ever dared to do before. Soon, she was taking more trouble over her appearance, and began to play the hit record ‘People Will Say We’re in Love,’ from the musical Oklahoma! incessantly on the gramophone.

In May, in an atmosphere of continuing uncertainty, Philip went to Salem for the second marriage of his sister Tiny, whom he had not seen for nine years, and whose first husband had been killed in the war. He told her about his relationship with Princess Elizabeth. ‘He was thinking about getting engaged,’ Tiny recalls. ‘Uncle Dickie was being helpful.’

There was as yet no engagement, official or unofficial. The real reason for Philip’s request for naturalization was coyly avoided in official memoranda – though the involvement of senior members of the Government indicated that it was known or suspected. Publicly, a pretence had to be kept up. If the Prince and Princess were present at the same party, they did not dance together, as a precaution.

However, there were clues which led to leaks. The addition of Philip’s name to the guest list for Balmoral in 1946, when it had not been included on the advance list, aroused much below-stairs interest at the Palace.

A pattern developed which became the norm with royal betrothals: stories in the foreign press, picked up by British popular newspapers, followed by Palace denials whose cautious nature fuelled speculation. In September 1946, after a year of mounting gossip, Sir Alan Lascelles took the novel step of repudiating reports of an engagement, but without commenting on the future possibility of one. The story finally broke, not in words but – and it was another significant precedent – on celluloid: a newsreel shot of an exchange of tender glances at the wedding of Lord Mountbatten’s daughter Patricia to Lord Brabourne, as Philip, an usher, helped Elizabeth, a bridesmaid, with her fur wrap.

A Greek plebiscite took place on 1 September 1946, restoring the Greek Monarchy: the restoration of George II, however, so far from reducing the political embarrassment of an alliance with the Greek dynasty, increased it, by highlighting King George’s legacy of authoritarian rule.

In the meantime, the issue of Philip’s national status, even his eligibility, as a foreigner, for a peacetime commission in the Royal Navy, remained unresolved. At first, he was told he could stay in the Navy;

then the Admiralty had second thoughts, and ruled that his retention depended on his naturalization.

Matters ground to a virtual halt. The obstacle continued to be the attitude of the Government but also, it had become clear, the coolness of the Court. Faced with a Kafka-like civil service, a hesitant British King, and his dubious set of advisers, Uncle Dickie decided to harass the Palace.

It did the trick. The Palace’s patience snapped. Following one particularly vigorous piece of Mountbatten lobbying, Lascelles informed the King somewhat testily that Dickie had telephoned him yet again on the subject of Prince Philip’s naturalization, and that he had suggested that, as Prince Philip’s uncle and guardian, there was no reason why he should not take up the matter himself, without reference to the Monarch.