По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

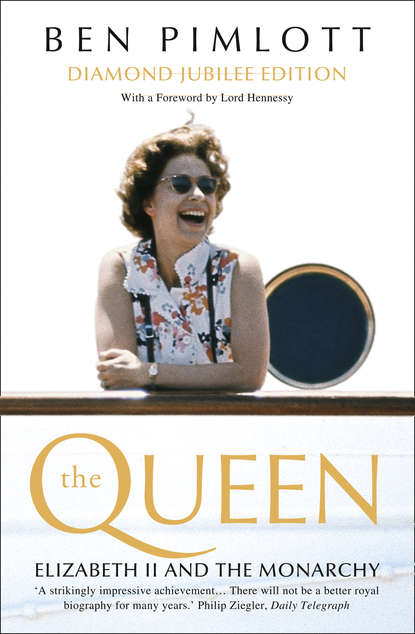

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Here it is particularly difficult to separate image from reality, because witnesses to royal domesticity were subject to the same media messages as everybody else, and the dutiful Windsors themselves, hounded by the pressures of what was expected of them, were on their best behaviour when being observed. In the context of such necessary and powerful myths, the royal actors had little choice but to play their allotted parts.

Would Edward VIII, had he lasted, have been selfish and truculent in wartime, or would he have risen to the occasion? It is an interesting speculation. As it was, the stammering King whom some had believed could not survive the ordeal of being crowned, seemed able to adapt in war, as in peace, to the requirements of his job. These consisted mainly of being photographed, taking part in public ceremonies, and personally bestowing honours – sometimes, because of the fighting, decorating several hundred servicemen in a single session. It also involved, and this was an especially vital role, making important visitors feel pleased to have had the opportunity of meeting him and his family. Surprisingly, this became something that George VI was particularly good at. The strange combination of his own social ineptitude, the Queen’s ability to make whoever she addressed feel that they were the one person to whom she wished to speak, and their daughters’ lack of affectation, provided a recipe for putting people at their ease.

Were they as genuinely pleased to see an endless flow of visitors as they seemed, or was it all act? Noël Coward asked himself this question after experiencing what he called ‘an exhibition of unqualified “niceness” from all concerned’ during a meeting with the Royal Family in 1942. He concluded that it did not matter. Putting oneself out was part of the job of royalty. ‘I’ll settle for anyone who does their job well, anyhow.’

Few others, however, came away feeling that it was just for show. For most who encountered the Family informally, the wonder of being in the presence of Monarchy in an Empire at war was combined with an uplifting sense of inclusion, as if they themselves were family members. The result was a miasma of shared affection, of which the grateful visitor felt both spectator and part. When Queen Alexandra of Yugoslavia (herself a refugee) met them in 1944, she immediately decided that ‘this was the sort of home life I wanted, with children and dogs playing at my feet.’

General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who spent a shooting weekend with them in Norfolk in the same year, came away with a similar feeling – recording his impression of ‘one of the very best examples of family life. A thoroughly close-knit and happy family all wrapped up in each other.’

Nobody referred, in their descriptions of the King, to his intellectual capacities, his political judgement, or his knowledge of the war. Yet so far from being a handicap, George VI’s limitations – and his awareness of them – were turned into a precious source of strength. One Gentleman Usher fondly described him as ‘a plodder’ – a man of simple ideas, with a strong sense of what he ought to do. Much was made of such decent ordinariness, which meant confronting what others had to face without complaint – and included such self-denials as not seeking to escape the Blitz, or trying to give his daughters a privileged immunity from danger by sending them with other rich children to Canada. It also meant frugality, and strict obedience to government rules – a topic which played a major part in the use of royalty for propaganda. Thus, in April 1940, the public was informed that at the celebration of Princess Elizabeth’s fourteenth birthday, the Queen had decreed that the three-tier anniversary cake should be limited to plain sponge, as an economy.

There were many tales of economy with clothing coupons, and of how the Queen cut down and altered her own dresses for Elizabeth, adapting these in turn for Margaret, so that ‘with the three of us, we manage in relays’.

This was not just for public consumption. When Eleanor Roosevelt visited Buckingham Palace late in 1942, she found an adherence to heat, water and food restrictions that was almost a fetish. Broken window panes in her bedroom had been replaced with wood, and her bath had a painted black line above which she was not supposed to run the water.

Nevertheless, there remained a wide gulf between the life lived by the Royal Family, with their houses, parks and horses, and retinue of servants, and the conditions of their subjects. After a bomb struck the Palace, the Queen was supposed to have said: ‘Now we can look the East End in the face’. The East End, however, was not able to retreat to Windsor to catch up on sleep, or to spend recuperative holidays in Norfolk and Scotland. Nor was the East End able to supplement its diet with pheasants and venison shot on the royal estates.

Indeed some aspects of royal life went on remarkably undisturbed. There was little interruption to the riding lessons given to the princesses by Horace Smith, which continued throughout the war. Training with Smith involved pony carts, which (as he later observed) had the particular advantage in wartime that journeys in them did not require petrol. With future troop-reviewing in mind, Smith also taught Princess Elizabeth to ride side-saddle. Occasions for demonstrating equestrian prowess did not cease, either. In 1943, Smith personally awarded Princess Elizabeth first prize in the Royal Windsor Horse Show for her driving of a ‘utility vehicle,’ harnessed to her own black Fell pony – a trophy she won again the following year, both times in the presence of the King and Queen.

Watching was a developing interest, as well as riding or driving. In the spring of 1942, the Princess was taken by her parents to the Beckhampton stables on the Wiltshire Downs, where horses bred at the royal studs were trained, to see two royal horses, Big Game and Sun Chariot, which were highly fancied for the Derby and the Oaks. The jockey Sir Gordon Richards later recalled his meeting with the sixteen-year-old girl ‘who took them all in’, and was quizzed about them by her father as they worked, causing the royal trainer Fred Darling to remark loyally ‘that Princess Elizabeth must have a natural eye for a horse’. Visits to see the mares and foals at the royal stud at Hampton Court, and to see the royal horses in training at Newmarket followed.

Other pursuits also involved opportunities not available to most compatriots. In October 1942, Princess Elizabeth made her contribution to the royal larder by shooting her first stag in the hills at Balmoral – using a rifle she had been taught to handle the previous year.

In the autumn of 1943, she hunted with the Garth Foxhounds, and later with the Duke of Beaufort’s Hounds in Gloucestershire.

The decision to allow her to go hunting was taken, according to a report, ‘in accord with the general policy of making her life as “normal” as possible’ in the light of her position as Heiress Presumptive.

There were also private entertainments. The King, despite his shyness, was a good dancer, and especially enjoyed dancing in the company of his children. He did not allow the war to curtail this particular pastime. A number of royal balls were held. Princess Elizabeth attended her first at Windsor in July 1941, when she was fifteen. A West End dance band played foxtrots, waltzes and rumbas to the Royal Family and their guests, who included Guards officers, until two in the morning, and Elizabeth danced several times with her father.

Later in the war, before the start of flying bombs in 1944, dances were held fortnightly in the Bow Room on the ground floor at Buckingham Palace. On one occasion the King, oblivious to cares of state, his stammer forgotten, led his family and other guests in a conga line through the corridors and state rooms.

FOR MAXIMUM BENEFIT to the war effort, the privacy of the Royal Family needed to be less than complete. If life at Windsor and Buckingham Palace had been simply private, its exemplary virtues could scarcely have been known to loyal subjects. For this reason, as The Times observed just after the end of the war, ‘many glimpses’ of the Royal Family’s home life had ‘reached a wide public, through illustrated journals and the cinema’.

One avid supplier to the illustrated journals, and propagator of royal mythology, was the photographer Lisa Sheridan who, by her own testimony, never failed to come away from a professional visit to the Royal Family without feeling a better person. Her recollections of the princesses in wartime are interesting not only because her pictures of wagging puppy tails, happy children and proud parents became fixed in the Empire’s imagination, but also because she provides a distillation of the ‘family of families’ miasma in its purest form.

In her memoirs, Mrs Sheridan described several wartime trips to see the princesses. Her account of the first, to Royal Lodge in early 1940, reflected the official line of the phoney war period, that the enemy had done little to change the traditional British way of life. The windows ‘showed no signs of criss-cross sticky tape or nasty black-out’. The princesses were intent on their normal recreations. When she arrived, they were dressed for riding and carried crops; they changed into ‘sensible’ tweed skirts and pullovers, in order to be photographed in the garden, suitably equipped with rakes and barrows, digging for victory. The overriding impression, however, was of the Windsors as a household anyone would like to be part of. Apart from the King and Queen and a policeman at the gate, nobody else was visible. ‘I never felt the presence of anyone at all other than the family,’ she recalled. It was clear ‘that home was to the Royal Family the source of life itself and that there was a determination on the part of the King and Queen to maintain a simple, united family life, whatever calls there might be to duty’. Later visits reinforced this picture of self-containment, though the background shifted from the unchanging domesticity of Royal Lodge to the warlike ramparts of the Castle. Here there were parables of life and death: the demise of a pet chameleon, for example (‘Princess Elizabeth could not bring herself to speak of her tiny pet for quite a long time after his death’) and, even more painfully, the death of a favourite corgi. The Queen, however, as always comforting and wise, told her elder daughter to keep things in proportion. It was, after all, the height of a world war.

Sheridan’s photographs, disseminated among dusty desert rats, weary Bevin boys, homesick land girls and traumatized evacuees, show a precious, sheltered intactness. In Sheridan’s world, the princesses were happily free from the requirement to do anything except obligingly change their outfits, and display an exquisite politeness. Yet they were also shown to be greatly concerned about the worrying state of a world mercifully beyond their comprehension – a concern that helpfully linked the ‘perfect hearth’ portrayal of the photographic image to a view of the girls which provided the regular diet of Ministry of Information handouts: as dutiful models for every other daughter of the Empire too young to serve in the women’s services.

A series of newspaper reports involving Princess Elizabeth, in particular, were designed, not so much to idealize the Heiress Presumptive, as to indicate royal approval for Government-sponsored schemes. Thus, the princesses did not only dig for victory, they knitted for it – the product of their labours being divided, with judicious impartiality, between the men of the army, navy and air force.

When they ran out of materials, there was a solution: in July 1941 it was announced that the two girls, aged fifteen and eleven, had personally arranged, and performed in, a concert in front of their parents and members of the armed services, from which between £70 and £80 had been raised, ‘to buy wool for knitting for the Forces’. If a Ministry wished to exhort the population to greater efforts, or advertise an achievement, it turned to the Palace for help, and where appropriate, royal children were provided. On one occasion the princesses (to the envy of every school child) were shown over a Fortress bomber, and allowed to play with the controls. On another, orchestrated publicity was given to the Queen’s decision to have both of them immunized against diphtheria. On yet another, the Heiress Presumptive was designated by the Ministry of Works as the donor of a prize open to Welsh schoolchildren ‘for the best essay in English and Welsh on metal salvage.’

Meanwhile, there was a press story in 1941 about how the fifteen-year-old Princess (despite a Civil List income of £6,000 a year) was only allowed five shillings a week pocket money; and that more than half even of this small sum was generously donated to war-supporting good causes.

The same spring, royal dolls owned by the children were exhibited to raise money for the British War Relief Society,

and a special ‘Princess Elizabeth’s Day’ was announced, for collecting for children’s charities.

How could any teenager cope? One answer is that royalty lived its life in compartments: the public sectioned off from the private and, in the case of a young princess, often barely touching her personally at all. Another is that teenagers had not yet been invented – or at any rate, young people in their teens in the early 1940s had very different expectations from those either before or after the war. The Second World War was a time when adolescence was held in suspension. Children who went straight from school into war work or the armed services, enjoyed no intervening period of irresponsibility. In this, Princess Elizabeth was not unusual. The acceptance of a variety of honorific titles or the performance of symbolic acts was not necessarily more stressful than the tasks and ways of life of many contemporaries. Nevertheless, at a stage in life when it is hard enough to keep everyday private events in perspective, such a cacophony of public roles provided a strange accompaniment to growing up.

She was like other girls of her age, yet not like them. Winston Churchill was supposed to have remarked in an unflattering reference to Clement Attlee, that if you feed a grub on royal jelly, it becomes a queen. In the case of a human Heiress Presumptive, the equivalent of royal jelly is the world’s perceptions: the drip feed of curtseys, deference, public recognition, combined with a knowledge of lack of choice, and of inevitability. The strongest instinct of many adolescents is to conform: it was an instinct with which Princess Elizabeth was well equipped. She seems to have dealt with the peculiarity of her position by becoming as unremarkable as possible in everything she could not change, while accepting absolutely what was expected of her. Her actual experience was unique: there was nobody with whom she could compare herself, no peer group to set a standard. Yet few young people could have been more conformist, more amenable, than George VI’s elder daughter.

There remains the difficulty for the rest of humanity – grubs without a destiny – in understanding the mentality of somebody with such extraordinary expectations. A distinctive character, however, was beginning to emerge. Authentic portraits are rare – vignettes by passing visitors are generally coloured by excitement at meeting royalty, and tell more about the witness than the subject. But there are enough thoughtful descriptions to confirm the part-flattering, part-disconcerting impressions provided by Crawfie, of a reserved, strong-willed, narrow-visioned, slightly priggish child, without intellectual or aesthetic interests, taking what she is given as part of the natural order, but with greater mental capacities than any close member of the family cared to appreciate. When she was still thirteen, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Lang, noted after ‘a full talk with the little lady alone’ before he conducted her confirmation service, that ‘though naturally not very communicative, she showed real intelligence and understanding’.

More than two years later, Eleanor Roosevelt formed a view of her that was strikingly similar. The wife of one Head of State assessed the daughter of another as ‘quite serious and a child with a great deal of character and personality . . . She asked me a number of questions about life in the United States and they were serious questions.’

The experience of her as an able, but above all single-minded, young person was shared by Horace Smith, who had more contact with her during the war than any of her other teachers apart from Crawfie, and who taught her in the subject that interested her most. The Princess was not, he considered, ‘a person who takes up interests lightly, only to drop them just as easily a short time later. If and when her interest is aroused, she goes into whatever subject it is with thoroughness and application, nor does her interest wane with the passing of time or the claim of other new matters upon her attention.’ In addition, he noted, she had ‘a keen and retentive mind’.

Such perceptions were combined, however, with a sense that she was young for her age, and remained in appearance and manner still a child until well into her teens. Perhaps there was an element of wishful thinking: the princesses’ childhood was part of the status quo ante bellum which it was hoped to restore. Such a feeling may have been strongest of all in the King and Queen, who liked her to wear the clothes of a child after she had ceased to be one. Nevertheless an uncertainty about whether Princess Elizabeth was precocious or immature, or both, is a recurrent feature of the accounts. Chips Channon observed the princesses in procession at a service at St. Paul’s in May 1943, ‘dressed alike in blue, which made them seem like little girls’.

Peter Townsend, an RAF officer who joined the Royal Family as an equerry to the King nine months later, found that they were not too old to lead him in a ‘hair-raising bicycle race,’ and recalled Princess Elizabeth as ‘charming and totally unsophisticated’.

Alexandra of Yugoslavia’s recollection of meeting her British cousins at Windsor, describes a childish ritual involving the princesses and their dogs. When tea was brought in, they insisted on feeding (with the aid of a footman) their four corgis first.

Preparation for her osmosis from child-princess, locked in a tower with her schoolbooks or playing in the park with her sister, to constitutionally responsible Heiress, was scratchy, like much else in wartime. For some time, the Crawfie and Marten regime had been supplemented with French lessons from the Vicomtesse de Bellaigue. According to one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, Lady Helen Graham, Elizabeth had been encouraged to attend closely to the news bulletins of the BBC.

‘Already the Princess has a first-rate knowledge of State and current affairs,’ a courtier declared in 1943.

Various accounts were given of the level of her knowledge, some of them doubtless exaggerated, in order to demonstrate her fitness for the tasks ahead. It was said that, in addition to French, she was fluent in German. When she was eighteen, The Times claimed she was highly musical and although ‘like some others of her sex, she is no mathematician,’ she was familiar with ‘many classics’ in English and French.

When a magazine editor wrote to the Palace to check a list, supplied by ‘a friend near the Court,’ of books and authors the Princess had allegedly read, a courtier replied firmly that the list could be published as correct. It consisted of ‘many of Shakespeare’s plays,’ Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Coleridge, Keats, Browning, Tennyson, Scott, Dickens, Austen, Trollope, Stevenson, Trevelyan’s History of England, Conan Doyle, Buchan and Peter Cheyney.

To this remarkably large collection might be added the Brontës: at the end of the war, Lisa Sheridan found the Princess reading Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, and expressing a preference for historical novels and stories about the Highlands.

Was it true? If such accounts were even half accurate, the Princess would have been a strong candidate for a place at university, where she might have extended her intellectual range. Neither university nor even finishing school, however, was considered as a possibility. Instead, like a butcher or a joiner, she apprenticed for the job she would be undertaking for the rest of her life by doing it.

Her first practical experience of the grown-up world of royalty was to head a regiment. In January 1942, following the death of the Duke of Connaught, she was asked to take his place as honorary Colonel of the Grenadier Guards – a natural choice, some felt, in view of her contact with the Grenadiers at Windsor. The offer was accepted, and on her sixteenth birthday she carried out her first engagement as Colonel at Windsor Castle, inspecting the Grenadiers in the company of her father. Thirty reporters and ten photographers were granted press passes to cover the event.

Cecil Beaton marked it with one of his most famous pictures, which shows the Heiress Presumptive in uniform, fresh-faced and half-smiling, with her jacket unbuttoned and her hat at a coquettish angle. Afterwards, she was hostess to more than six hundred officers and men, entertained by the comedian Tommy Handley.

The Grenadier Guards were delighted by their acquisition, and those who dined with her in the officers’ mess recall her as ‘charming, and very sincere’.

Yet despite this dramatic début, Buckingham Palace kept up the fiction that the Princess was still a child, and American press requests for help with a story about her were met with the incomprehensible denial that she was entering public life.

Adulthood could not be postponed for ever. Princess Elizabeth’s coming-of-age, when she was entitled to succeed to the throne without need for a Regent, took place when she was eighteen, in April 1944. There was no débutante ball to celebrate the occasion. Instead, it was accompanied by the Princess’s graduation from a nursery bedroom to a suite. Here she was pictured by Lisa Sheridan, as if she were part of the interior design. ‘The upholstery is pale pink brocade patterned in cream,’ it was revealed. ‘The walls are cream, hung with peaceful pictures of pastoral scenes. The Princess’s flowered frock harmonized admirably with her room.’

There were other changes, to mark her rise in status. She was assigned her own armorial bearings, and her own standard which flew in whatever residence she happened to be occupying. She also acquired a ‘Household’ of her own, including, in July 1944, a lady-in-waiting. Meanwhile, she had unwittingly stimulated a minor constitutional controversy which engaged the best legal brains for several months.

The 1937 Regency Act, which had been passed following George VI’s accession, had provided for two forms of delegation of royal powers: to a Regent, in the event of a child under eighteen succeeding, or of the total incapacitation of a monarch; and to five Counsellors of State, composed of the Consort and the four next in line of succession, in the event of the Sovereign’s illness or absence abroad. However, the provision disqualified anybody not ‘a British subject of full age,’ which effectively meant that Elizabeth could succeed her father as Monarch with full powers at eighteen, but not deputise for him as a Counsellor until she was twenty-one.

Nobody noticed this anomaly until an eagle-eyed lawyer pointed it out to the King’s private secretary, Sir Alexander Hardinge, in the autumn of 1942. Hardinge at first dismissed it. It was ‘common sense,’ he replied to the lawyer tartly, to regard the Princess as fully of age if she could succeed without a Regent.

The Lord Chancellor, Lord Simon, however, disagreed: due to bad drafting, the law and common sense did not coincide.

There the matter might have rested, had not the King himself indicated his desire to have his daughter as a Counsellor of State. The Lord Chancellor was once again consulted, and recommended to the Prime Minister that the law be changed in order to permit the Heiress Presumptive to become a Counsellor, bearing in mind ‘the qualities of the young lady and the wish of her parents’.

As Allied troops invaded Sicily in July 1943, George VI spoke to Winston Churchill on the matter, and secured a promise that it should be brought up at War Cabinet, with a view to a quick Bill. ‘He quite agrees this should be done,’ wrote the King.