По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

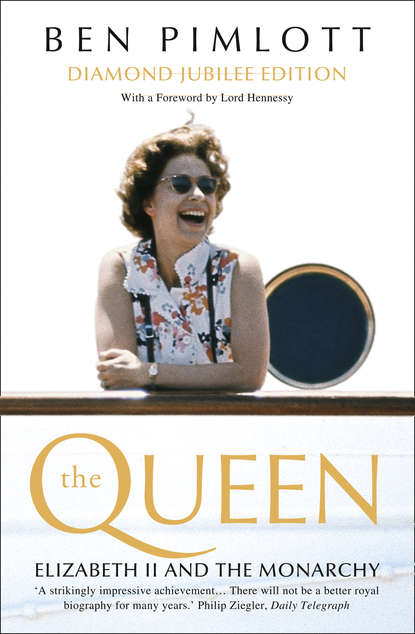

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The whole Royal Family, together with the whole political and Church Establishment, and many ordinary people, were shocked and appalled by the prospect of an abdication, which seemed to strike at the heart of the constitution. But nowhere was it viewed with greater abhorrence than at 145 Piccadilly. According to his official biographer, the Duke of York viewed the possibility, and then the likelihood, of his own succession with ‘unrelieved gloom’.

The accounts of witnesses suggest that this is a gross understatement: desperation and near-panic would be more accurate. To succeed to a throne you neither expected nor wanted, because of the chance of birth and the irresponsibility of a brother! Apart from the accidents of poverty and ill health, it is hard to think of a more terrible and unjust fate.

Alan (‘Tommy’) Lascelles, assistant private secretary to Edward VIII and later private secretary to George VI, wrote privately that he feared Bertie would be so upset by the news, he might break down.

There were lurid stories: that the Duke of York had refused to succeed, and that Queen Mary had agreed to act as Regent for Princess Elizabeth.

Rumours circulated in the American press that the Duke was epileptic (and that Princess Margaret was deaf and dumb).

There was also a whispering campaign, in which Wallis Simpson played a part, that he had ‘a slow brain’ which did not take on ideas quickly and that he was mentally unfit for the job.

On 27th October, when Mrs Simpson obtained a decree nisi, the shadow darkened. The Duke braced himself for the catastrophe, as he saw it, that was about to befall his family and himself. ‘If the worst happens & I have to take over,’ he wrote, with courage, to a courtier on 25 November, ‘you can be assured that I will do my best to clear up the inevitable mess, if the whole fabric does not crumble under the shock and strain of it all.’

Meanwhile, Crawfie and the children took refuge from the atmosphere of tension by attending swimming lessons at the Bath Club, with the Duke and Duchess sometimes turning up to watch.

A week later, the press’s self-imposed embargo on ‘King-tattle’ broke, and the headlines blazoned the name of Mrs Simpson. The Royal Archives contain a chronicle, written by Bertie, which shows the extent of his misery, bordering on hysteria, as he awaited what felt like an execution. In it, he describes a meeting with his mother on December 9th, when the Abdication had become inevitable, and how ‘when I told her what had happened I broke down and sobbed like a child’. There are few more poignant testimonies in the annals of the modern Monarchy than George VI’s account of the occasion he most feared, but could do nothing to prevent:

‘I . . . was present at the fateful moment which made me D’s successor to the Throne. Perfectly calm D signed 5 or 6 copies of the instrument of Abdication & then 5 copies of his message to Parliament, one for each Dominion Parliament. It was a dreadful moment & one never to be forgotten by those present . . . I went to R.L. [Royal Lodge] for a rest . . . But I could not rest alone & returned to the Fort at 5.45. Wigram was present at a terrible lawyer interview . . . I later went to London where I found a large crowd outside my house cheering madly. I was overwhelmed.’

A kind of fatalism took over the Duke, now the King, as the Court which had surrounded – and sought to protect and restrain – his brother, enveloped him, guiding him through the ceremonies of the next few days. There was nothing he could do, except what he was told, and nothing for his family to do except offer sympathy. According to Crawfie’s account, the princesses hugged their father before he left 145 Piccadilly, ‘pale and haggard,’ for the Privy Council in the uniform of an Admiral of the Fleet.

To Parliament and the Empire, and the man now called Duke of Windsor, the Abdication Crisis was over. But for King George VI and, though she did not yet appreciate it, his elder daughter, Heiress Presumptive to the Throne, it had just begun.

Chapter 3

SIXTY YEARS LATER, it is still hard to assess the impact of the Abdication of Edward VIII. Arguably it had very little. In the short run, politics was barely affected; there was no last minute appeal by the resigning Monarch for public support, as some had feared there might be; no ‘King’s party’ was put together to back him. Indeed, the smooth management of the transition was a cause for congratulation, and was taken to show the resilience of the Monarchy, and the adaptability of the constitution. Even social critics regarded it as evidence of English establishment solidarity. ‘To engineer the abdication of one King and the enthronement of another in six days,’ wrote Beatrice Webb, ‘without a ripple of mutual abuse within the Royal Family or between it and the Government, or between the Government and the Opposition, or between the governing classes and the workers, was a splendid achievement, accepted by the Dominions and watched by the entire world of foreign states with amazed admiration.’

Nevertheless, it has always been treated as a turning point, and in an important sense it was one. It broke a spell.

In the past, public treatment of the private behaviour of members of the Royal Family had contained a double standard. Since the days of Victoria and Albert, the personal life of royalty had been regarded as, by definition, irreproachable; while at the same time occasionally giving cause for disapproval or hilarity – as in the case of Edward VII when Prince of Wales, and his elder son, the Duke of Clarence. Not since the early nineteenth century, however, had it been a serious constitutional issue. The Abdication made it one – giving to divorce, and to sexual misconduct and marital breakdown, a resonance in the context of royalty, which by the 1930s it was beginning to lose among the upper classes at large. At the same time the dismissal of a King provided a sharp reminder that British monarchs reigned on sufferance, and that the pomp and sycophancy counted for nothing if the rules were disobeyed. During the crisis, there was talk of the greater suitability for the throne of the Duke of Kent – as if the Monarchy was by appointment. It came to nothing, but the mooting of such a notion indicated what the great reigns of the past hundred years had tended to obscure – that Parliament had absolute rights, and that the domestic affections of the Royal Family were as much a part of the tacit contract between Crown and people as everything else.

In theory, the British Monarchy was already, and had long been, little more than a constitutional convenience. How could it be otherwise, with a Royal Family whose position had so frequently depended on parliamentary buttressing, or on a parliamentary decision to pass over a natural claimant in favour of a more appropriate minor branch? ‘If there was a mystic right in any one,’ as Walter Bagehot put it dryly in 1867, ‘that right was plainly in James II.’

Yet, in practice, there had been accretions of sentiment and loyalty which had allowed the obscure origins of the reigning dynasty to be forgotten. As a result, a traditional right or legitimacy had replaced a ‘divine’ one, and a great sanctity had attached to laws of succession unbroken for more than two centuries. The Abdication cut through all this like a knife – taking the Monarchy back as far as 1688, when Parliament had deprived a King of his throne on the grounds of his unfitness for it.

On that occasion, the official explanation was that James II had run away – though in reality there were other reasons for wishing to dispose of a monarch who caused political and sectarian division. In 1936, the ostensible cause of the King’s departure was his refusal to accept the advice of his ministers that he could not marry a divorced woman. Yet the Government’s position was also regarded as a moral, and not just a technical or legalistic one. The King’s relationship with Mrs Simpson was seen as symptomatic. The nation, as one commentator put it, took a dim view of tales of frivolity, luxury and ‘an un-English set of nonceurs’, associated with the new King and minded seeing its throne ‘provide a music-hall turn for low foreign newspapers’.

Although the decision to force Edward VIII to choose between marriage and his crown was reluctant, it was accompanied by a hope and belief that his successor – well-married, and with a family life that commanded wide approval – would set a better example.

But the Monarchy would never be the same again. ‘All the King’s horses and all the King’s men,’ Jimmy Maxton, leader of the left-wing Independent Labour Party, reminded the House of Commons, ‘could not put Humpty-Dumpty back again.’

Not only was the experience regarded, by all concerned, as chastening: there was also a feeling that, though the Monarchy would survive, it had been irrevocably scrambled. Even if George VI had possessed a more forceful character, the circumstances of his accession would have taken from the institution much of its former authority. As it was, the Monarchy could never again be (in the words of a contemporary writer) ‘so socially aggressive, so pushy’ as under George V;

nor could it be so brash as under Edward VIII, whose arrival ‘hatless from the air,’ in John Betjeman’s words, had signalled a desire to innovate. After the Abdication, George VI felt a need to provide reassurance, and to behave with a maximum of caution, as if the vulgar lifting of skirts in the autumn of 1936 had never happened. Yet there could be no simple return to the old position of the Monarch as morally powerful arbitrator, a role played by George V as recently as 1931. Under George VI, royal interventions, even minor ones, diminished. The acceptance of a cypher-monarchy, almost devoid of political independence, began in 1936.

If the Abdication was seen as a success, this was partly because of an accurate assessment that the genetic dice had serendipitously provided a man who would perform the functions of his office in the dutifully subdued way required of him. Indeed, not only the disposition of the Duke of York but the familial virtues of both himself and his wife had been a key element in the equation. The point had been made by Edward VIII in his farewell broadcast, to soften the blow of his departure, when he declared that his brother ‘has one matchless blessing, enjoyed by so many of you and not bestowed on me – a happy home with his wife and children.’

It was also stressed by Queen Mary, when she commended her daughter-in-law as well as her second son to the nation. ‘I know,’ she said with feeling and with meaning, ‘that you have already taken her children to your hearts.’

Everybody appreciated that if the next in line had happened to be a footloose bachelor or wastrel, the outcome might have been very different. As it was, the Duke of York – despite, but perhaps also because of, his personal uncertainties – turned out to be well suited to the difficult task of doing very little conscientiously: a man, in the words of a contemporary eulogizer, ‘ordinary enough, amazing enough, to find it natural and sufficient all his life to know only the sort of people a Symbol King ought to know,’ and, moreover, one who ‘needs no private life different from what it ought to be.’

To restore a faith in the Royal Family’s dedication to duty: that was George VI’s single most important task. There was a sense of treading on eggshells, and banishing the past. As the Coronation approached, the regrettable reason for the King’s accession was glossed over in the souvenir books, and delicately avoided in speeches. The monarchist historian Sir Charles Petrie observed a few years later that there was a tendency to forget all about it, ‘and particularly has this been the case in what may be described as official circles’.

It was partly because the memory of the episode was acutely painful to the King and Queen, as well as to Queen Mary, but it was also because of the embarrassment Edward VIII’s abdication caused to the dynasty, and the difficulty of incorporating an act of selfishness into the seamless royal image. Burying the trauma, however, did not dispose of it, and the physical survival of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor – unprotected by a Court, and often teetering on the brink of indiscretion or indecorum – provided a disquieting shadow, reminding the world of an alternative dynastic story.

By contrast, the existence of ‘the little ladies of 145 Piccadilly’ gave the new Royal Family a trump card. If, in the eyes of the public, the Duchess of Windsor was cast as a seductress, the little ladies offered cotton-clad purity, innocence and, in the case of Princess Elizabeth, hope. It greatly helped that her virtues, described by the press since babyhood, were already well-known. What if she had inherited her uncle’s characteristics instead of her father’s? Fortunately the stock of attributes provided by the sketch-writers did not admit of such a possibility. The ten-and-a-half-year-old Heiress Presumptive, it was confidently observed, possessed ‘great charm and a natural unassuming dignity’. The world not only already knew, but already loved her, and hoped that one day she would ‘rule the world’s greatest Empire’ as Queen.

The discovery that she had become a likely future Monarch, instead of somebody close to the throne with an outside chance of becoming one, seems to have been absorbed by Princess Elizabeth gradually. Although her father’s accession, and the elimination of doubt about the equal rights of royal daughters, placed her first in line, it was not yet certain that she would ever succeed. When Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent was told of her expectations at almost precisely the same age in March 1830, she was reported by her governess to have replied ‘I will be good’. According to Lady Strathmore, when Princess Elizabeth received the news, she ‘was ardently praying for a brother’.

It was still imaginable: the Queen was only thirty-six at the time of the Coronation in May 1937, and shortly before it a rumour spread that she was pregnant.

Increasingly, however, a view of the future with Princess Elizabeth as Monarch was widely accepted. There was even some speculation that Elizabeth might be given the title of Princess of Wales.

According to her sister, the change of status was something they knew about, but did not discuss. ‘When our father became King,’ recalls Princess Margaret, ‘I said to her, “Does that mean you’re going to be Queen?” She replied, “Yes, I suppose it does.” She didn’t mention it again.’

There was also the matter of where they lived. According to Crawfie, Princess Elizabeth reacted with horror when she was told that they were moving to Buckingham Palace. ‘What – you mean for ever?’ According to Princess Margaret, the element of physical disruption was limited. 145 Piccadilly was only a stone’s throw from Buckingham Palace, and they had often gone over to see their grandparents, and to play in the garden.

Perhaps the distrust was more in the mind of the governess, who likened setting up home in the Palace to ‘camping in a museum’.

The living quarters were, in any case, soon domesticated after the long era of elderly kings and queens. Elizabeth’s menagerie of toy horses acquired a new setting; and a room overlooking the Palace lawns, which had briefly been her nursery in 1927, was established as a schoolroom.

More important than the change of location was the ending of a way of life. In the months before the Coronation, public attention became unrelenting. Outside the railings at Buckingham Palace, a permanent crowd formed. Inside them, it was impossible to keep up the illusion of being an ordinary family. At 145 Piccadilly, there had been few visitors, most of whom were personal friends. At the Palace, the King had to see visitors or take part in functions for much of the day, and the Queen was busy every afternoon. Before, the little girls had been able to take walks in the park and play with the children of neighbours. At the Palace, royal headquarters of an Empire, there were no neighbours and different standards applied. A famous anecdote illustrated the change. Princess Elizabeth discovered that merely by walking in front of a sentry on ceremonial duty, she could make him present arms; and having made the discovery, she could not resist walking backwards and forwards to see it repeated.

There was a sense of constraint, as well as of power. According to Lajos Lederer, the accession brought an immediate change to Princess Elizabeth’s previously relaxed sittings for Strobl. A detective now accompanied her everywhere, a policeman was always outside, and she ‘no longer referred to Mummy and Papa, but spoke of the King and Queen’.

The Queen seems to have been responsible for taking customary formalities seriously, and seeing that her children did so too. According to Dermot Morrah (a trusted royal chronicler), she insisted ‘that even in the nursery some touches of majesty were not out of place, an argument that had the full approval of Queen Mary’.

One ‘touch of majesty’ involved the serving of nursery meals by two scarlet-liveried footmen. In addition, though nursery food was mainly ‘plain English cooking,’ the menu, for some reason, was in French.

The biggest strain for the Royal Family, however, was the almost intolerable pressure placed upon the new King as he came to terms with his unsought and unwelcome role. ‘It totally altered their lives,’ according to Lady Mountbatten. ‘To begin with, the King would come home very worried and upset.’

George VI’s speech impediment, always a handicap, became a nightmare, and every public appearance a cause of suffering. Although British journalists tactfully avoided mentioning it, foreign ones were less reticent. To the American press, suspicious that the real reason for the Abdication was Mrs Simpson’s American nationality, he remained ‘the stuttering Duke of York’.

The Queen had always taken pleasure from public occasions, and continued to display a much-admired serenity: but the King at first seemed so gauche and unhappy that doubts were raised about whether he could get through his Coronation.

HE MANAGED it none the less. In the early spring of 1937, British newspapers which had loyally kept silent about Mrs Simpson, now loyally built up George VI as a ‘George V second edition’.

Yet there was a sense of him not just as the substitute but also as a reluctant Monarch. Kingsley Martin summed up the mood thus, apostrophizing the thoughts of a supposedly typical member of the public: ‘We would still prefer to cheer Edward, but we know that we’ve got to cheer George. After all, it’s Edward’s fault that he’s not on the throne, and George didn’t ask to get there. He’s only doing his duty, and it’s up to us to show that we appreciate it.’

Martin noted a feeling of relief and sympathy, as much as of rejoicing, and of healing a personal wound.

The Coronation itself had a wider function than the consecration of a new King. It was also Britain putting its best face to the world – the more urgently so because of the international crisis which overshadowed the royal one. Many commentators, viewing the celebration with its hotch-potch of religion, nostalgia, mumbo-jumbo and military display, saw it simultaneously as a reminder to potential aggressors of British imperial might and a reaffirmation of British freedom. For such purposes, the Empire was unblinkingly described as if it were a democratic, almost a voluntary, association.

Comparisons were proudly drawn between the symbols of liberty parading through the streets of London, and the choreographed vulgarities of European fascism. One fervent royalist saw George VI’s Coronation as ‘a pageant more splendid than any dictators can put on: beating Rome and Nuremberg hollow at their own bewildering best, and with no obverse side of compulsion or horror’.

The anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski reckoned it a sound investment, as ‘a ceremonial display of the greatness, power and wealth of Britain,’ generating ‘an increased feeling of security, of stability, and the permanence of the British Empire’.

Even the Left was impressed. Kingsley Martin agreed with the view that the British Establishment had upstaged Goebbels – and suggested that the propaganda purpose of the procession and festivities was to show that the Empire was still as strong and united as in 1914, and that Britain suffered from less class conflict than any other nation.