По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

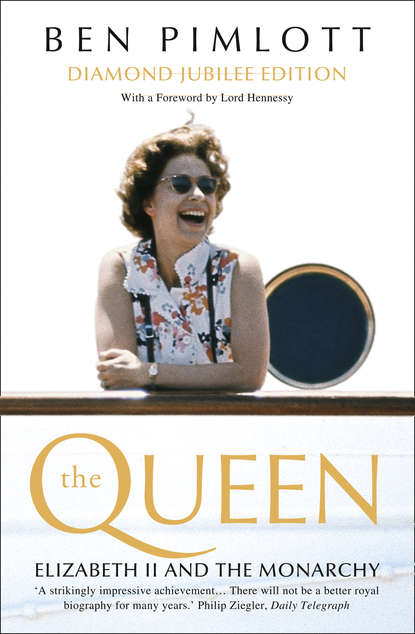

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Horses and dogs had to be trained, and from a tender age, Princess Elizabeth was often portrayed in appropriate roles of command and authority in relation to them. But royal children required training too, and it was made clear, in every tale, that the Princess’s mischief was never allowed to get out of hand. If Elizabeth had a sense of fun, it was also (commentators took care to point out) kept in check. ‘Uncurbed without being spoilt’ was how the Sunday Dispatch described the barely walking child in an article entitled ‘The Roguish Princess’.

‘Roguish’ was a favourite term in such accounts: it implied misbehaviour within acceptable and endearing limits. According to Alice Ring’s royally sanctioned description of the Princess, published in 1930, on one occasion Elizabeth said ‘My Goodness!’ in the hearing of her mother. She was ‘at once told that this was not pretty and mustn’t be repeated’. However, if she heard an adult use the unseemly expression, ‘up go her small arms in a gesture of mock amazement, and she presses her palms tightly over her mouth while her blue eyes are full of roguish laughter’.

Uncurbed was never allowed to mean over-indulged. ‘I don’t think any child could be more sensibly bought up,’ Queen Mary remarked. ‘She leads such a simple life and she’s always punished when she’s naughty.’

Here was a useful moral tale, for the edification of millions. ‘Once Lisbet had been naughty, for even princesses can be naughty, you know,’ wrote Captain Eric Acland, author of a particularly cloying biography published when Elizabeth was twelve, ‘and her mother, to punish her, refused to tell the usual bedtime story.’

According to another writer, if the Duchess of York was asked what her main duty was, ‘she would reply, “Bringing up my children”. She brings them up as she herself was brought up, with unremitting care and great practical intelligence.’

It was the accepted view. ‘No child of Queen Elizabeth’s will ever be spoilt,’ the writer Stephen King-Hall summed up, at the time of George VI’s Coronation.

But how could any child receive so much attention, and be the object of so many admiring glances, yet not be spoilt, even allowing for parental firmness? Here was an even deeper paradox in the iconography, never satisfactorily resolved. The usual answer – and the one that dominated characterizations of the Princess until her adolescence – was that her innocence was protected, as if by wall and moat, from the corrupting effects of vulgar fame and even of excessive loyal adoration. Chocolates, china sets and children’s hospital wards, even a territory in Antarctica, were named after her; the people of Newfoundland had her image on their postage stamps; songs were written in her honour, and sung by large assemblies of her contemporaries; while Madame Tussaud’s displayed a wax model of her astride a pony. However, according to one chronicler in the early 1930s, ‘of all this she is unconscious, it passes her completely by – and she remains just a little girl, like any other little girl . . . and passionately fond of her parents’.

There was also the idea of a fairy-tale insulation from the projected thoughts and fantasies of the outside world – a ‘normal’ childhood preserved, by an abnormal caesura, from public wonder. ‘In those days we lived in an ivory tower’ wrote Elizabeth’s governess, many years later, ‘removed from the real world’.

Yet the very protection of the Princess, the notion of her as an innocent, unknowing, unsophisticated child who, but for her royal status, might be anybody’s daughter, niece or little sister, helped to sustain the popular idea of her as a ray of sunshine in a troubled world, a talisman of health and happiness. This particular quality was often illustrated by tales of her special, even curative, relationship with the King, which juxtaposed youth and old age, gaiety and wisdom, the future and the past, in a heavily symbolic manner. From the time of the Yorks’ Australian tour, when the Princess was fostered at Buckingham Palace, it had been observed that the ailing Monarch, whose health was becoming a matter of concern throughout the Empire, derived a special pleasure from the company of his granddaughter.

There were many accounts which brought this out. ‘He was fond of his two grandsons, Princess Mary’s sons,’ the Countess of Airlie recalled, ‘but Lilibet always came first in his affections. He used to play with her – a thing I never saw him do with his own children – and loved to have her with him’.

Others observed the same curious phenomenon: on one occasion, the Archbishop of Canterbury was startled to encounter the elderly Monarch acting the part of a horse, with the Princess as his groom, ‘the King-Emperor shuffling on hands and knees along the floor, while the little Princess led him by the beard’.

When she was scarcely out of her pram, a visitor to Sandringham reported watching the King ‘chortling with little jokes with her – she just struggling with a few words, “Grandpa” and “Granny”’.

The Princess’s governess recalled seeing them together, near the end of the King’s life, ‘the bearded old man and the polite little girl holding on to one of his fingers’. Later, it was claimed that the King was ‘almost as devoted a slave to her as her favourite uncle, the Prince of Wales’.

Yet it was also stressed that she was taught to know her place. Deferential manners were an ingredient of the anecdotes, alongside the spontaneity. One guest noted that after a game of toy bricks on the floor with an equerry, she was fetched by her nurse, ‘and made a perfectly sweet little curtsey to the King and Queen and then to the company as she departed’. This vital piece of royal etiquette had been perfected before her third birthday. When it was time to bid her grandfather goodnight, she would retreat backwards to the door, curtsey and say, ‘I trust your Majesty will sleep well’.

Some accounts took the Princess’s concern beyond mere politeness. For example, it was said that when the King was sick, she asked after him, and, on seeing her grandmother, ‘flung herself into the Queen’s arms and cried: “Lillybet to see Grandpar today?”’

There were also reports that when the royal landau passed down Piccadilly a shrill cry was heard from the balcony at No. 145: ‘Here comes Grandpa!’ – causing the crowd to roar with loyal delight.

There was much approval, too, for her name for the King: ‘Grandpa England’.

But the most celebrated aspect of the relationship concerned the Princess’s prophylactic powers during the King’s convalescence from a near-fatal illness in the winter of 1928–9. During this anxious time, the little girl ‘acted as a useful emollient to jaded nerves,’

a kind of harp-playing David to the troubled Monarch’s Saul.

In March 1929, the Empire learnt that the Princess, not yet three, was being encouraged to spend much of the morning with the recuperating King in his room at Craigweil House in Bognor, in order to raise his spirits. For an hour or so, she would sit with him by his chair at the window, making ‘the most amusing and original comments on people and events’.

The King recovered, and his granddaughter was popularly believed to have played a part in bringing this about. Many years later, Princess Elizabeth told a courtier that the old Monarch’s manner ‘was very abrupt, some people thought he was being rude’.

The fact that he terrified his sons, and barked at his staff, gave the stories of the little girl’s fearless enchantments an even sharper significance.

For her fourth birthday in 1930, the doting old man made Elizabeth the special gift of a pony. At this news public adoration, both of the giver and the recipient, literally overflowed. The same day, the Princess, in a yellow coat trimmed with fur, was seen walking across the square at Windsor Castle, with a band of the Scots Guards providing an accompaniment. Women waved their handkerchiefs and threw kisses. The Princess waved back, and ‘her curly locks fluttered in the breeze’. The sight was too much for the crowd. People outside the Castle gate suddenly pressed forward, and swept the police officer on duty off his feet.

Chapter 2

THE DUCHESS OF YORK gave birth to a second child at Glamis Castle in August 1930. Although a Labour Government was now in office, traditional proprieties were once again observed – this time at even greater inconvenience to the new Home Secretary, J. R. Clynes, than to his predecessor. Summoned north for the expected event, Clynes was kept waiting for five days as a guest of the Countess of Airlie, at Cortachy Castle. He made no complaint, and seems to have enjoyed his part in the ritual. Later he described how, after the announcement, ‘the countryside was made vivid with the red glow of a hundred bonfires, while sturdy kilted men with flaming torches ran like gnomes from place to place through the darkness’.

The arrival of Princess Margaret Rose had several effects. One was to reinforce public awareness of her sister. The child was not a boy, the King’s health remained uncertain, and the Prince of Wales showed no sign of taking a wife. A minor constitutional controversy, following the birth, helped to remind the public that Elizabeth’s position was an increasingly interesting one. Although common sense indicated that, after the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York, she remained next in line, doubts were raised about whether this was really the case. Some experts argued that legally the two sisters enjoyed equal rights to the succession: there was nothing, in law, to say that they did not, and the precedence of an elder sister over a younger had never been tested. The King ordered a special investigation. The matter was soon settled, to the satisfaction of the Court, and as the Sovereign himself no doubt wished.

Another effect was to give Elizabeth a companion, and the public an additional character on which to build an ever-evolving fantasy. The Yorks were now a neatly symmetrical family, the inter-war ideal. There were no more children to spoil the balance, or dilute the cast. After the birth of Margaret Rose, 145 Piccadilly acquired a settled, tranquil, comforting air, and the image of it became a fixed point in the national and imperial psyche. When people imagined getting married and setting up a home, they thought of the Yorks. The modest, reserved, quietly proud father, the practical, child-centred mother, the well-mannered, well-groomed daughters; the ponies, dogs and open air; the servants dealing with the chores, tactfully out of sight; the lack of vanity, ambition, or doubt – all represented, for Middle England and its agents overseas, a distillation of British wholesomeness.

It did not matter that the Yorks were not ‘the Royal Family’ – that the Duke was not the King, or ever likely to be. Indeed, it helped that they were sufficiently removed from the ceremonial and servility of the Court to lead comprehensible lives, and for their daughters to have the kind of fancy-filled yet soundly based childhood that every boy and girl, and many adults, yearned for. At a time of poverty and uncertainty for millions, the York princesses in their J. M. Barrie-like London home and country castles stood for safety and permanence. The picture magazines showed them laughing, relaxed, perpetually hugging or stroking pets, always apart from their peers, doll-like mascots to adorn school and bedroom walls. Children often wrote to them, as if they were playmates, or sisters: little girls they already knew. Story books spun homely little tales around their lives, helping to incorporate them as imaginary friends in ordinary families.

The most dramatic attempt to appropriate them for ordinariness occurred in 1932, with the erection of a thatched cottage, two-thirds natural size, by ‘the people of Wales,’ as a present for Princess Elizabeth on her sixth birthday. This remarkable object made an implicit point, for no part of the United Kingdom had suffered more terrible unemployment than the mining valleys of the principality. Built exclusively by Welsh labour out of Welsh materials, it provided a stirring demonstration of the ingenuity of a workforce whose skills were tragically wasted. At the same time – loyally and movingly – its creators sought to connect the lives of the little Princess and her baby sister to those of thousands of children who inhabited real cottages. The point, however, could not be too political, and an abode, even an imitation one, intended for a princess had to be filled with greater luxuries than average families ever experienced.

Great efforts were made to ensure that it conformed to the specifications of a real home. Electric lights were installed, and the contents included a tiny radio, a little oak dresser and tiny china set, linen with the initial ‘E’, and a portrait of the Duchess of York over the dining-room mantelpiece. The house also contained little books, pots and pans, food cans, brooms, and a packet of Epsom salts, a radio licence and an insurance policy, all made to scale. The bathroom had a heated towel rail. In the kitchen, the reduced-size gas cooker, copper and refrigerator worked, and hot water came out of the tap in the sink.

It was scarcely a surprise present. Months of publicity preceded its completion. There was also a near-disastrous mishap. When the house was finished and in transit, the tarpaulin protecting it caught fire, and the thatched roof and many of the timbers were destroyed. Though some felt it lucky that the incendiary nature of the materials had been discovered before, and not after, the Princess was inside, the project was not abandoned. Instead, indefatigable craftsmen worked day and night to repair the damage and apply a fire-resistant coating, in time to display the renovated house at the Ideal Home Exhibition at Olympia.

Then it was reconstructed in Windsor Great Park for the birthday girl, and became a favourite plaything.

Whatever Elizabeth may have made of the house’s message, she and her sister were soon using it for the purpose for which it was intended: to exercise and display their ordinariness. Elizabeth was ‘a very neat child,’ according to her governess, and the Welsh house provided an excellent opportunity to show it. The two girls spent happy hours cleaning, dusting and tidying their special home.

Thousands of people who had experienced a vicarious contact with royalty by inspecting the cottage when it was on public show, were later able to enjoy a series of photographs of the elfin princesses, filling the doorway of ‘Y Bwthyn Bach’ – the Little House – not just as children but as Peter Pan adults, miniaturized in a securely diminutive world, the perfect setting for the fantasy of ‘royal simplicity’. The contrast between the oriental extravagance of the structure – fabulously costly in design, equipment, production and delivery – and the games that were to be played in it, highlighted the triumphant paradox.

It was also, of course, a female artefact, a point made by Lisa Sheridan, when the children proudly took her on a tour in 1936:

In the delightful panelled living-room everything was in its proper place. Not a speck of dust anywhere! Brass and silver shone brilliantly. Everything which could be folded was neatly put away. The household brushes and the pots and pans all hung in their places. Surely this inspired toy provided an ideal domestic training for children in an enchanted world . . . Everything in the elegantly furnished house had been reduced, as if by magic, to those enchanting proportions so endearing to the heart of a woman. How much more so to those young princesses whose status fitted so perfectly the surroundings?

Y Bwthyn Bach gave Elizabeth a Welsh dimension. A Scottish one was provided shortly afterwards by the appointment, early in 1933, of a governess from north of the border, Marion Crawford. In a sense, of course, Elizabeth was already half-Scottish, and it was the Scottish networks of the Duchess of York that had led to the appointment. However Miss Crawford belonged to a different kind of Scotland from the one known to the Bowes-Lyons, or – for that matter – to the kilt-wearing Windsor dynasty. A twenty-two-year-old recent graduate of the Moray House Training College in Edinburgh, she came from a formidable stratum: the presbyterian lower middle class.

Miss Crawford stayed with the Yorks, later the Royal Family, teaching, guiding and providing companionship to both girls for fourteen years, until she married in 1947, shortly before the wedding of Princess Elizabeth. Three years later, she published a detailed account of her experiences in the royal service, against the express wishes of the Palace. ‘She snaked,’ is how a member of the Royal Family describes her behaviour today.

Perhaps it was the incongruity of a woman from such a background betraying, for financial gain, the trust that had been placed in her (as her employers came to see it) which accounted for the anger that was felt. She was not the last to snake, but she was the pioneer. Marion Crawford was soon known as ‘Crawfie’ to the princesses: ‘doing a Crawfie’ became an expression for selling family secrets, especially royal ones, acquired during a period of personal service. To the modern reader, however, Miss Crawford’s Little Princesses is a singularly inoffensive work. Composed with the help of a ghost writer in a gushing Enid Blyton, or possibly Beverley Nichols, style, it does not destroy the Never-Never-Land mythology of 145 Piccadilly, but embraces it. Love, duty and sacrifice are the currency of daily life, and everybody always acts from the best of motives. Yet the book also has perceptiveness – and the ring of authenticity. Although effusively loyal in tone, it reveals a sharp and sometimes critical eye, and opinions which were not always official ones.

It shows a character with just enough of a rebellious edge to make the subsequent ‘betrayal’ explicable. Until she became notorious, Crawfie and her presence at the Yorks’ hearth were regarded in the press (perhaps rightly) as evidence of the Bowes-Lyon belief in no-nonsense training for young girls. According to The Times on the occasion of Princess Elizabeth’s eighteenth birthday, Miss Crawford ‘upheld through the years of tutelage the standards of simple living and honest thinking that Scotland peculiarly respects’.

When the Duke of York became King, she was also felt to provide a politically useful bond between the kingdoms. The most important point about Crawfie, however, which escaped public attention at the time, was that she had aspirations, both for her charges and for herself.

She was no scholar, and seemed to share the Royal Family’s indifference to academic and aesthetic values. Yet she did not share its lack of curiosity, and she had a strong, indignant sense of the Court as old-fashioned and remote. She deplored what she saw as the children’s ignorance of the world, and her book – perhaps this was the most infuriating thing about it – describes her personal crusade to widen the little girls’ horizons. There was a Jean Brodie, charismatic aspect to Miss Crawford, both in the power of her passionate yet selfishly demanding personality (sometimes she seemed to forget who was the princess) and in her evangelical determination to make contact with life outside. Although for part of the time she had Queen Mary as an ally, it was an uphill struggle. She did, however, take the children on educational trips, and conspired to satisfy their desire to travel on the London tube; and her greatest triumph was to persuade her employers, by then King and Queen, to allow a Girl Guide Company to be set up at Buckingham Palace. She was also a woman of her age: her other ambition was to get married, something which was incompatible with her employment and – if her own account is to be believed – one which her employers could never understand.

Crawfie was not a contented person. Indeed, the self-portrait unwittingly contained in her book suggests a rather lonely and restless one, an immigrant to England and an outsider to a strange tribe whose members, though friendly, persisted in their unusual and disturbing customs. She was a taker as much as a giver. But she was interesting, intelligent and forceful. Patricia (now Lady) Mountbatten – daughter of Louis and Edwina, and a second cousin of the princesses – remembers her from Guide meetings in the Buckingham Palace gardens as a tall, attractive, highly competent woman, ‘with a good personality for bringing out somebody like Princess Elizabeth, who had a stiff upper lip ingrained from birth.’

There seems to have developed a mutual dependence, as she became, during critical years, the princesses’ confidante and friend.

PRINCESS ELIZABETH’S earliest years had been spent at 145 Piccadilly with her parents, at Glamis Castle and St. Paul’s Walden Bury with one set of grandparents, or at Balmoral and Sandringham with the other. In 1931, the Yorks were granted Royal Lodge, in Windsor Great Park, by the King, and in the following year they took it over as their private country residence. Thereafter, the adapted remnant of George IV’s cottage orné designed by John Nash, with its large, circular garden, screening of trees, and air of rustic simplicity, became one of Princess Elizabeth’s most familiar homes. More than anywhere, Royal Lodge provided the setting for the Yorks’ domestic idyll. Summers were spent there with a minimum of staff.

From the point of view of family life, it was an advantage (not mentioned in the newspaper profiles) that the Duke had little to do. He went on the occasional overseas visit, though never again, as Duke of York, on the scale of the 1927 Australian tour; he exchanged hospitality with relatives and friends; he gardened, he rode, and he shot. With time on his hands, he was often at home during the day and able to take luncheon with his family, and to play tag or hide-and-seek with his daughters in Hamilton Gardens. Until 1936 he and his wife seemed perfectly content with the undemanding routines of a minor member of the Royal Family, of whom little was required or expected. The Duchess had been a society beauty, fêted and wooed in her youth. After contracting a surprising if elevated marriage, however, she appeared to have no ambitions beyond the settled rhythms of an unremarkable aristocratic life, and the enjoyment of her children. Though her wit and charm made her friends wherever she went, and endeared her to other members of the Royal Family, she and her husband were not a fashionable couple, and they had little contact with the café society which held such a fascination for the Prince of Wales.

Crawfie, who disapproved of some of the grander and crustier aspects of the royal way of life, repeatedly stressed in her book that the York establishment concentrated on the children. ‘It was a home-like and unpretentious household I found myself in,’ she wrote. Life at 145 Piccadilly, at least as seen from the perspective of the governess, revolved around the nursery landing, or around the sleeping quarters of the Duke and Duchess. ‘No matter how busy the day, how early the start that had to be made,’ according to Crawfie, ‘each morning began with high jinks in their parents’ bedroom.’ This was a daily ritual which continued up to the morning of Princess Elizabeth’s marriage. The day ended with a bath and a bedtime ritual, also involving parental high jinks. ‘Nothing was ever allowed to stand in the way of these family sessions.’

Sandwiched between morning and evening high jinks came the Princess’s education – or, as many observers have wryly observed – the lack of it. After breakfast with Alla in the nursery, Elizabeth would start lessons in a little boudoir off the main drawing-room, under the supervision of her governess. Later, she would make remarks (sometimes to put nervous, successful people at their ease) about her lack of proper schooling; and it is true that, even for a princess born out of direct line of succession to the throne, her curriculum was far from exacting.

According to a tactfully understated assessment in the 1950s, it was ‘wide rather than deep’ without any forcing, or subjection to a classical discipline.

It was, perhaps, a misfortune that there were no peers to offer competition, or examinations to provide an incentive. Most time was spent on English, French and history.