По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

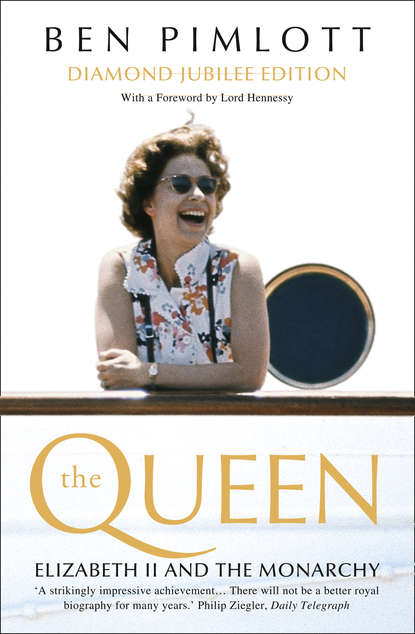

The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Franklin on the popularity of the Monarchy in Australia (News International Newspapers Ltd./John Frost Historical Newspaper Service. Published in the Sun 29th February 1992)

Bell ‘Orff with her ring!’ (Steve Bell. Published in the Guardian 22nd December 1995)

Bell ‘The way ahead senior royals think tank’ (Steve Bell/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Guardian, 20 August 1996)

Cummings ‘I’m having a ghastly nightmare that the photographers stopped invading my privacy!’ (Mrs M. Cummings/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in The Times, 16th August 1997)

Griffin ‘The Queen of all our hearts’ (Express Newspapers/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in The Daily Express, 1st September 1997)

Gerald Scarfe ‘The Tidal Wave’ (Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Times, 7 September 1997)

Unny on the Queen (The Indian Express (Bombay). Published in The Indian Express, 12th October 1997)

Trog on the death of Diana, Princess of Wales (Wally Faukes/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Telegraph, 7th September 1997)

Gerald Scarfe on the Australian referendum (Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Sunday Times, 7th November 1999)

Mac ‘So Sophie. After that absolutely abysmal performance, you are the weakest link – goodbye’ (Atlantic/Centre for the Study of Cartoons, University of Kent. Published in the Daily Mail, 9th April 2001)

Queen Elizabeth II 1926

FOREWORD

TO THE DIAMOND JUBILEE EDITION

Had Ben Pimlott been with us in the run-up to 2012, the print and electronic media would have made his telephone number and email the first to which they turned for a Diamond Jubilee assessment of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. To understand why is captured between these covers. The pages to come are the product of what happened when a leading political biographer and a top-flight historian of the twentieth century, the gifts combined in Ben’s person, took a long and serious look at the formation, the functions, the style and the adaptability of the lady whom we Brits of the post-war era were, and are, so fortunate to have as our Head of State.

Ben was naturally superb at calibrating the fluidities of our political and constitutional streams as they touched and occasionally refashioned the ancient banks of the Monarchy. He set the Queen’s reign in the context of all the wider changes to her UK realm on her road from 1952 – withdrawal from Empire; the long, reluctant retreat from great powerdom; our emotional deficit with Europe; a social revolution or two; and considerable changes in the size and make-up of our population. Through all these shifts, the Queen has been a gilt-edged constant who, in my judgement, has never put a court shoe wrong as a constitutional sovereign even though as a country we are entirely without a written highway code for Monarchy, relying on conventions and a constitution which, as Mr Gladstone wrote, ‘presumes more boldly than any other the good sense and good faith of those who work it’. Good sense and good faith are the prime requirements of a British and Commonwealth constitutional monarch and the Queen possesses both in abundance.

Ben Pimlott understood all this and illustrated it through all his pages, not one of which was dully written. He also had a sure touch when it came to the emotional geography of the wider landscapes where the Sovereign, the Royal Family and the people meet. He, for example, was the pilot we – and future historians – needed through the days and the swirls and the eddies that followed the death of Princess Diana in 1997. I have a suspicion that it was Ben who gave Alastair Campbell the description ‘the People’s Princess’ which the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, took up in his reaction to the tragedy in Paris. Ben was very good at mapping the Queen’s and the Palace’s recovery from the wobble in public esteem of September 1997. And it’s fascinating to think what Ben might have made now of the sixty-year spectrum of the Queen’s reign – of the self-restoring powers of the British Monarchy and of the enduring qualities of Queen Elizabeth which have always been a lustrous asset in tough times as well as the easier stretches in the life of her nation.

It is always difficult to winnow out the personal premium from the good standing of the institution of Monarchy (there are usually two-thirds of those polled in the United Kingdom in favour of it). The Queen came to the throne at a time when we were dripping with deference as a society. We are scarcely moist now. Yet the esteem for the Queen remains. As Head of State, she has always enhanced the great office she holds. The same cannot be said of others – not least some of those who have held the headship of government as Prime Minister in No. 10 Downing Street. And one scans the world in vain for another sixty-year example of faultless public duty. The Queen could not have had better personal trainers than her father, King George VI, and her mother, Queen Elizabeth. But, in sporting terms, it’s as if she had won gold at every Olympics from Helsinki in 1952 to London in 2012.

Ben Pimlott, too, won gold by writing this book and gold standard it will remain. For I will be surprised if, when the Queen’s official biographer is appointed, it’s not Pimlott on Elizabeth II that’s the first book for which he or she will reach on the shelf.

Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield, FBA

Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History

School of History, Queen Mary, University of London

LondonMarch 2012

FOREWORD

TO THE GOLDEN JUBILEE EDITION

In my Preface to the paperback edition of The Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth II, published a year after the hardback, I excused myself for not adding new material by saying that ‘an extra chapter would be part of another book’. I meant that any historical account is a snapshot, not just of its subject matter, but of the attitudes of the author when it is written. In this sense, The Queen: Elizabeth II and the Monarchy is another book. The first edition of The Queen was researched and written in the mid-nineties. It appeared in 1996, the year of the divorce of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and doubtless reflects that timing. This Golden Jubilee edition has been prepared several years later. It contains not one additional chapter, but five. The result is a book which has an altered shape from the original, while at the same time offering in the extra chapters a different snapshot.

Chapters 1 to 23 are little changed. There are a few corrections and stylistic tightenings, but I have not attempted to revise my interpretation. The new material is contained in Chapters 24 to 28. Here I have examined post-1996 events and sought to place them in the context of the Queen’s life and reign as a whole. I have also looked more closely – partly in the light of ‘Diana week’ – at aspects of the Monarch’s role that go beyond the purely constitutional or symbolic. If there is a new theme, it has to do with the ancient (but also apparently continuing) concept of ‘royalty’. At the same time, I have tried to integrate the added chapters so that the reader who comes to the book afresh can take it as a single work, and move from old to new without too great a sense of the division. The revised title is intended to indicate the shift in the book’s centre of gravity, and also to distinguish this edition from earlier ones.

I have included the original (hardback) Preface, and I would like to repeat my thanks to the people listed there, many of whom have been re-interviewed or who have given help with this edition in other ways. In particular, I would like to record my unique debt to the late Lord Charteris – a great royal and public servant with whom I spent many happy, instructive and sometimes hilarious hours in the cell-like interview rooms of the Palace of Westminster, and whose voice I often used to illuminate my text. In addition, I should like to thank the staff of the Buckingham Palace press office, and especially Geoff Crawford and Penny Russell-Smith, successively Press Secretaries to the Queen; together with Mary Francis, Peter Galloway, David Hill, Stephen Lamport, Robin Ludlow, Lady Penn, Frank Prochaska and a number of others who prefer not to be named. I should once again like to give my special thanks to Arabella Pike of HarperCollins, for her encouragement and ever incisive advice. I should also like to thank Aisha Rahman for her care and efficiency in guiding the Golden Jubilee edition through to publication. Caroline Wood has again provided invaluable help as picture researcher. At Goldsmiths, I am extremely grateful to Edna Pellett for typing an illegible (sometimes even to the author) manuscript with astonishing skill and without reproach. I would also like to thank Jef McAllister, London Bureau Chief of Time Magazine, and the staff at the Australian High Commission, for their kindness in providing access to newspaper and other files; and Dan and Nat Pimlott for their resourcefulness in sifting through them.

New Cross, London SE14 September 2001

PREFACE

‘What a marvellous way of looking at the history of Britain’, said Raphael Samuel, when I told him about this book. Others expressed surprise, wondering whether a study of the Head of State and Head of the Commonwealth could be a serious or worthwhile enterprise. Whether or not they are right, it has certainly been an extraordinary and fascinating adventure: partly because of the fresh perspective on familiar events it has given me, after years of writing about Labour politicians; partly because of the human drama of a life so exceptionally privileged, and so exceptionally constrained; and partly because of the obsession with royalty of the British public, of which I am a member. Perhaps the last has interested me most of all. To some extent, therefore, this is a book about the Queen in people’s heads, as well as at Buckingham Palace. It is, of course, incomplete – no work could be more ‘interim’ than an account of a monarch who may still have decades to reign. However, because the story is still going on with critical chapters yet to come, it is also – more than most biographies – concerned with now.

It is an ‘unofficial’ study, and draws eclectically on a variety of sources. For the period up to 1952, the Royal Archives have been invaluable; documentation up to the mid or late 1960s has been provided by the Public Record Office and the BBC Written Archive Centre, alongside a number of private collections of papers, listed at the end of this book. For later years, interviews have been particularly helpful. In addition, there is a wealth of published material.

I have a great many individual debts. I am extremely grateful to Sir Robert Fellowes (Private Secretary to the Queen and Keeper of the Royal Archives, Charles Anson (Press Secretary to the Queen), Oliver Everett (Assistant Keeper of the Royal Archives) and Sheila de Bellaigue (Registrar of the Royal Archives) for assisting with my requests whenever it was possible to do so.

I would like to thank Anne Pimlott Baker, principal researcher for the book, for the care and resourcefulness of her inquiries, and for her skilful digests and research notes; Andrew Chadwick, for research into the archives of The Times and News of the World; Sarah Benton, for reading the whole text in draft and making many perceptive comments on it; Anne-Marie Rule for typing the manuscript with her usual combination of speed, precision and good-natured tolerance of unreasonable demands – the fifth time she has typed a book for me (am I the last author, incidentally, who still uses a pen and has his drafts typed on a pre-electric typewriter?); Terry Mayer and Jane Tinkler for their help in typing, and retyping, some of the chapters, and for many kindnesses; and my colleagues and students at Birkbeck, for their forebearance, interest and encouragement.

I am grateful to the many librarians and archivists, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, who have helped me in person, on the telephone, or by correspondence. In addition to those already mentioned, I would especially like to thank Jacquie Kavanagh at the BBC Written Archive Centre at Caver-sham Park, Helen Langley at the Bodleian Library and the library staff of The Times Newspapers and the Guardian. I am also particularly grateful to Sir Hardy Amies, for generously making available to me his corespondence with the Queen and members of the Royal Family over a period of more than forty years; to Phillip Whitehead, for letting me see the unedited transcripts of interviews for his television documentary, The Windsors; and Vernon Bogdanor and Frank Prochaska for showing me the text of their excellent recent books, before publication. I am deeply indebted to the staff of the British Library at Bloomsbury, who continue to provide an outstanding service, despite trying conditions during the countdown to the move (regretted by so many) to St Pancras.

I am grateful to the following for permission to quote copyright material: Arrow Books (D. Morrah To Be a King); Collins (H. Nicolson Diaries and Letters 1930–1939); Duckworth (M. Crawford The Little Princesses); Hamish Hamilton (R. Crossman The Backbench Diaries of Richard Crossman; The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister 1964–66); Hutchinson (T. Benn Out of the Wilderness: Diaries 1963–67); Macmillan (J. Wheeler-Bennett George VI: His Life and Reign).

I would like to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen for allowing me the privilege of using the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, and for granting me permission to quote from papers in the Archives. For the use of other unpublished papers and documents I am grateful to: Sir Hardy Amies (Amies papers); Lady Avon (Avon papers); Balliol College, Oxford (Nicolson papers); BBC Written Archive Centre (BBC Written Archives); British Library of Political and Economic Science (Dalton papers); Christ Church, Oxford (Bradwell papers); Churchill College, Cambridge (Alexander papers; Chartwell papers; Swinton papers); Lady Margaret Colville (Colville papers); Dwight D. Eisenhower Library (Eisenhower papers); Mrs Caroline Erskine (Lascelles papers); House of Lords (Beaverbrook papers); John F. Kennedy Library (Kennedy papers); Lambeth Palace (Fisher papers); F. D. Roosevelt Library (Roosevelt papers); Harry S. Truman Library (Truman papers); University College, Oxford (Attlee papers); University of Southampton (Mountbatten papers).

I would like to thank the following people who have taken the time to talk to me about different aspects of this book: Lord Airlie, Lady Airlie, Ronald Allison, Sir Hardy Amies, Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, Sir Shane Blewitt, Lord Brabourne, Sir Alistair Burnet, Lord Buxton, Lord Callaghan, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Carnarvon, Lord Carrington, Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, Lord Charteris, Lord Cranborne, Jonathan Dimbleby, Lord Egremont, Sir Edward Ford, Princess George of Hanover, The Duchess of Grafton, John Grigg, Joe Haines, David Hicks, Lady Pamela Hicks, Anthony Holden, Angela Howard-Johnston, Lord Howe, Lord Hunt of Tamworth, Douglas Hurd, Sir Bernard Ingham, Michael Jones, Robin Janvrin, Lord Limerick, Lady Long-ford, Brian MacArthur, Lord McNally, HRH Princess Margaret, Sir John Miller, Sir Derek Mitchell, Lady Mountbatten, Michael Noakes, The Duke of Norfolk, Commander Michael Parker, Michael Peat, Rt Rev Simon Phipps, Sir Edward Pickering, Sir David Pitblado, Sir Charles Powell, Enoch Powell, Sir Sonny Ramphal, Sir John Riddell, Kenneth Rose, Lord Runcie, Sir Kenneth Scott, Michael Shea, Phillip Whitehead, Sir Clive Whitmore and Mrs Woodroffe. I also spoke to others who prefer not to be named. Where it has not been possible to give the source of a quotation in the text or notes, I have used the words ‘Confidential interview’. None of these people, or anybody else apart from the author, is responsible for how the material has been interpreted.

HarperCollins has once again proved itself the Rolls Royce of British non-fiction publishing. I am particularly indebted to Stuart Proffitt, my publisher, for his persistent faith in the project and his shrewd author management, and to my incomparable editor, Arabella Pike, for whom my admiration has no bounds. I am also grateful to Caroline Wood for her inspired picture research, and to Anne O’Brien for vital last-minute help. Giles Gordon, my literary agent, has been a constant source of practical wisdom and advice.

Finally, I thank the people to whom the book is dedicated: my children, for keeping my spirits up; and my wife, Jean Seaton, for whom all my books are really written, whose thoughts about monarchy and royalty are now inextricably bound up with my own, and whose fertile historical imagination has been a daily quarry.

Bloomsbury, WC1 August 1996

Chapter 1

APRIL 1926 was a busy month for every member of the Conservative Government, but for few ministers more than the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks. A long, bitter dispute in the coalfields was moving rapidly towards its climax – with drastic implications for the nation.

‘We are going to be slaves no longer and our men will starve before they accept any reductions in wages,’ the miners’ leader, A. J. Cook, had declared in an angry speech that crystallized the mood in the collieries, while the men resolved: ‘Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day’. On 14 April, the TUC leadership asked the Prime Minister to intervene. A week later the owners and men met, but failed to reach agreement. Thereafter, the chance of a compromise diminished, and the prospect grew closer of a terrifying industrial shutdown which – for the first time in British history – seemed likely to affect the majority of British manual workers. Alarm affected all levels of society. Even King George V – mindful of his right to be consulted, and his duty both to encourage and above all to warn – discreetly urged his ministers to show caution. Alas, royal counsels were in vain, and the General Strike began at midnight on 3rd May 1926, threatening not just economic paralysis and bankruptcy, but the constitution itself.

‘Jix’ Joynson-Hicks – best known to history for his zeal in ordering police raids on the decadent writings of D.H. Lawrence and Radclyffe Hall, and for the part he later played in defeating the 1927 Bill to revise the Prayer Book – was scarcely an outstanding or memorable holder of his post. This, however, was his most splendid hour. In swashbuckling alliance with Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, Quintin Hogg and Leo Amery, the Home Secretary was a Cabinet hawk, in the thick of the fight, a scourge of the miners, opposed to an easy settlement.

If nothing else – it was said – he had nerve. It was Jix who, just after the Strike began, appealed for 50,000 volunteers for the special constables, in order to protect essential vehicles – and thereby raised the temperature of the dispute. For several critical weeks, Jix was at the heart of the nation’s events, in constant touch with the Metropolitan Police, and sometimes with the Prime Minister as well.

Sleep was at a premium, snatched between night-time Downing Street parleys and daytime consultations with officials. A call in the early hours of 21 April to attend a royal birth, shortly before one of the most critical meetings in the entire dispute between the Prime Minister and the coal owners, was therefore not entirely a cause for celebration. But it was a duty not to be shirked, and Joynson-Hicks was equal to it. He hurried to the bedside of the twenty-five-year-old Duchess of York, wife of the King’s second son, at 17 Bruton Street – the London home of the Duchess’s parents, the Earl and Countess of Strathmore, who happened to be among the most prominent coal owners in the United Kingdom. The child was born at 2.40 a.m., and named Elizabeth Alexandra Mary, after the Duchess and two Queens.

Why the Home Secretary needed to attend the birth of the child of a minor member of the Royal Family was one of the mysteries of the British Monarchy. Later, when Princess Elizabeth herself became pregnant, an inquiry was launched at the instigation of the then Labour Home Secretary, Chuter Ede. Inspecting the archives, Home Office researchers rejected as myth a quaint belief, fondly held by the Royal Household and the public alike, that it had something to do with verification, James II and warming pans. After taking expert advice, Ede informed Sir Alan Lascelles, Private Secretary to George VI, that it was no more than ‘the custom of past ages by which ministers thronged the private apartments of royalty daily, and particularly at moments of special significance such as births, marriages and deaths’.

In 1926, however, it was enough that it was customary – Jix was not the kind of man to question it. According to The Times the next day, Sir William ‘was present in the house at the time of the birth’ and conveyed the news by special messenger to the Lord Mayor.

It was a difficult delivery, despite the best attention. Not until 10 a.m. did the Duchess’s doctors issue a guarded statement which revealed what had happened. ‘Previous to the confinement a consultation took place,’ it declared, ‘. . . and a certain line of treatment’ – decorous code for a Caesarean section – ‘was successfully adopted’.

The announcement had more than a purely medical significance. The risks such an operation then entailed, and would again entail in the event of subsequent pregnancies, made it unlikely that the Duchess would have a large family, and hence reduced the chances of a future male heir.