По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

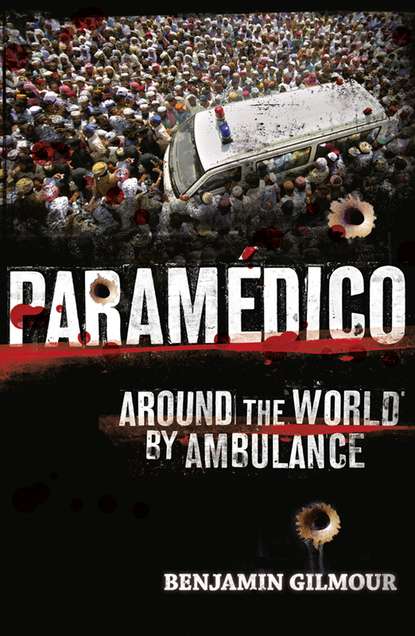

Paramédico

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He’s breathing.’

‘So? It’s agonal. You wanna tube him? Here,’ says The Leopard, casually opening the boot of the responder, retrieving his kit, passing it to me with his cigarette between his teeth, standing back again, entirely disinterested. Now that’s burnout, I think to myself. Typical burnout. Speeding to the scene, then doing nothing.

‘You won’t do it?’ I ask.

‘He’s chickenfeed, mate, all yours. Remember, don’t pivot on the teeth. If there’s blood in the airway, if you can’t see the cords, forget about it. We’re not going to stuff-up our suction this early in the shift.’

The vocal cords are Roman columns in the guy’s throat and I sink the tube easier than expected. Once connected to a bag, I breathe him up. The Leopard steps on his cigarette. He slinks over swinging his stethoscope casually, pops it in his ears and listens over each side of the chest and once over the stomach. Without saying a word he nods his approval. From the leather pouch at his waist he whips out a pen torch, flicks it over the wounded man’s eyes. The pupils are fixed on a middle distance, dilated to the edges, black as crude oil.

The Leopard chuckles.

‘Fok my, do all you people come here for learning miracles? Makes me lag, eh.’

He points to my knees either side of the patient’s head.

‘By the way, you’re kneeling in the brains.’

Early that morning I’d done a shift at Baragwaneth Hospital on the edge of Johannesburg’s sprawling Soweto townships. With three thousand beds it is one of the largest hospitals in the world and treats more than two thousand patients a day. Half of these are thought to be HIV positive. A constant stream of ambulances unloaded their sorry cargo onto rickety steel beds lined up side by side until, by mid-afternoon, there was barely room for any more. Teamed up with Simon, an Australian doctor with whom I’d participated in the ATLS, we cannulated, medicated and sutured non-stop.

While joining a doctor’s round in one of the wards, a boy of about sixteen was lying on a bed and as we passed by, he grabbed my wrist, pulling me close. His eyes pleaded as tears welled up and spilled onto his cheeks.

‘Please, friend, take it out, please take it out.’

On his right chest I could see a small bulge, the shape of a bullet sitting just beneath the epidermis. Exit wounds are not always a given, I’d learnt.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Treasure.’

‘What happened to you?’

‘Some men tried robbing me in Mofolo, I told them I had nothing to give but they klapped me hard and after I ran they shot.’

‘Bastards. Did it enter your back?’

‘Ja, bullet hit my spine, they told me it is shattered, they told me I am never walking again. When I fell down on the street I knew that. What will happen to me now? Last year my parents died in a minibus crash. There is no one to care for me.’

Already the doctors were three patients ahead – a ward round at Bara doesn’t wait. Treasure squeezed my arm tighter, sensing my urge to move on.

‘Please, brother, don’t go, please, take it out.’

‘Mate, I’m sorry for what happened to you, I really am. But the bullet is not interfering with any body function now, the damage is done. Maybe it will push out on its own one day.’

When I heard myself saying this to him – lying there unable to get up and walk to the open window, no father at the foot of his bed, no mother who named him her treasure holding his hand, no friends to help him pass the hours, the time he would forever spend turning over the memory of that one moment – I was filled with pity.

‘Just want this evil thing out,’ he said.

‘One minute,’ I told him. ‘I’ll bring a surgical kit.’

As I incised over the bullet, removing it with tweezers and dropping it into a steel kidney dish with a clink, I could feel Treasure’s muscles relaxing under the drape. A deep sigh passed his lips and his face smoothed out with relief.

‘God bless you, God bless you, God bless you,’ he whispered with his eyes closed, as if I had just exorcised an evil spirit. ‘God bless you forever.’

Among the pumps of a service station The Leopard unzips his bumbag. After looking around to make sure we are alone, he pulls out a 9mm semi-automatic handgun and slides out the magazine to show me its full load of rounds.

‘Got another one strapped to my ankle,’ he says.

With a sporadically effective police force, it is not unusual for paramedics to find themselves caught up in gunfights. Triage, the concept of sorting patients in multi-victim situations starting with the most critical, is superseded here by sheer self-preservation. If a member of one gang requests a paramedic to treat their own before those of an opposing group, it’s usually at gunpoint. The Leopard takes no chances.

‘Last year two of my colleagues were held up. Actually, it was an ambulance-jacking, they were left stranded in a bad place.’

As he drives me through Hillbrow, Johannesburg’s most densely populated urban slum of decrepit high-rise buildings, I see a neighbourhood I wouldn’t want to be stranded in either. Shopkeepers sit nervously behind thick iron bars and the blinking neon of pool halls and strip joints flickers on the figures of haggling prostitutes outside, their bodies shimmering with sweat.

‘Some of us call it Hellbrow. New Year’s Eve is the worst. People take pot shots with their guns from balconies, they let off fireworks horizontally, they throw furniture and other projectiles from windows, trying to hit people below. Few years back a fridge landed on a Metro ambulance. You never know what will come at you.’

Even ordinary party nights can be lethal in Jo’burg. Saturday evenings are difficult in most Western cities but here it’s a war-zone. Streets are jammed with people overflowing into the path of our car and the expectation of impending violence is palpable all around us. The Leopard locks the doors of the responder, says we’ll avoid the worst parts of the suburb, places even he won’t go unless accompanied by a police flying squad. He ignores red lights too, without being on a call. ‘You’ve got to keep moving. Robots will kill you in Johannesburg,’ he says, referring to the traffic signals. Rarely do I entertain irrational fears, but all heads seem turned on us tonight, eyes following the Audi as we pass, shady characters ready to pounce. In reality they could be just as well hoping we’ll stop and join them for a drink, take a break, have a laugh. But as we draw level with the next pub where words stencilled by the door read ‘No Guns Permitted’, I’m not so sure.

‘Zero Zero Three, come in.’

‘Three, go ahead.’

‘Man off a bridge, Yeoville.’

‘Rrrroger.’

Tossing individuals off bridges and towering apartment buildings is a preferred method of murder for some gangs in Jo’burg. Without witnesses and no weapon or identifying wounds, these deaths can be easily mistaken for suicide.

As The Leopard does a U-turn he points to the tallest building in Hillbrow, the notorious Ponte City Apartment block. This cylindrical skyscraper with a hollow core was built in 1975 as a luxury condo fifty-four storeys high. After the end of apartheid many gangs moved in and the penthouse suite on the top floor became the headquarters of a powerful Nigerian drug lord.

‘Once, we got half-a-dozen bodies in a week at the foot of that one,’ he says, flicking on the siren. But this was 2003 and things were changing. Using the South African Army as back-up, developers were evicting undesirables. Whether Ponte City’s former glory can be restored remains to be seen. Selling luxury apartments in the heart of a suburb where visiting the corner store for a carton of milk can get you killed will be tricky.

Half a minute down the road in Yeoville the traffic is backed up and we use the breakdown lane, our red and blue lights bouncing off the vehicles we pass. Under a freeway overpass we pull up behind a police van and see the officer in lane two standing over a young man lying face down, illuminated by the headlights of a late model Mercedes.

‘Lucky he missed the poor lady’s car, nice Merc that one,’ jokes the policeman. A woman in the front seat dabs her cheeks with a tissue.

I look up. The overpass is a good 20 or 25 metres high. No wonder the patient is groaning in agony. I’m surprised he’s even conscious.

Behind me The Leopard approaches with our gear. Seems the case has inspired him to show me what he’s made of. Or maybe the siren of our back-up ambulance wailing towards us has compelled him to act.

The policeman helps by manually stabilising the patient’s head. Calmly the Leopard scissors off the man’s shorts and T-shirt to expose him for a better examination. He slips a wide-bore IV into the cubital fossa without blinking and throws me a bag of Hartmann’s solution.

‘Five minutes on scene or we get docked,’ scoffs The Leopard. ‘Patient’s got an open-book pelvis with jelly legs, but it’s all about those five bloody minutes.’ He shakes his head and I know what he means. Time to hospital is the essence in trauma, but proper immobilisation, effective analgesia, cautious extrication and transport strategies will all, in the long run, reduce morbidity. Only by working the road can one truly appreciate ‘time’ as but one factor among many upon which an ambulance service should be judged.

Once the line is clear of air I connect and open it for a bolus. The Leopard double-checks the blood pressure, palpating seventy systolic. Falls from great heights often cause serious pelvic fractures like this, lacerating vessels internally and resulting in massive blood loss filling body cavities. This, in turn, can lead to absolute hypovolaemia – a condition of low blood volume – that could prove fatal.

‘Keep the fluids going wide open, we’ll shut it off at ninety systolic. Don’t go over ninety, got it?’

I nod.