По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

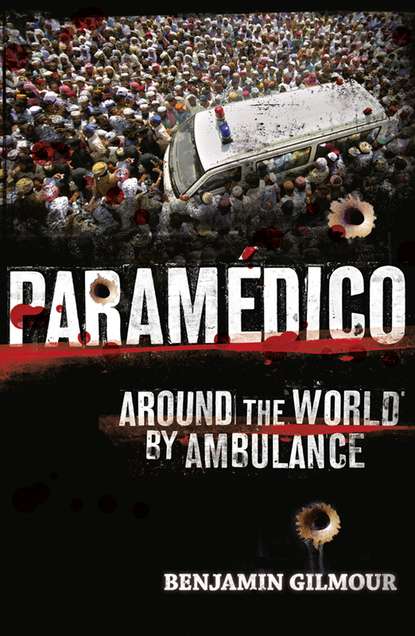

Paramédico

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Paramédico

Benjamin Gilmour

Around the world by ambulance.Paramédico is a brilliant collection of adventures by Australian paramedic Benjamin Gilmour as he works and volunteers on ambulances around the world. From England to Mexico, and Iceland to Pakistan, Gilmour takes us on an extraordinary thrill-ride with his wild coworkers. Along the way he learns a few things, too, and shows us not only how precious life truly is, but how to passionately embrace it.

To the men, women and children working on ambulances around the world.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u50194e03-4df3-56da-b4aa-20568f8a29eb)

TITLE PAGE (#u28931fcb-8b44-5c9f-9a3e-86006f7eb664)

DEDICATION (#uca5b3bda-af55-509c-aecb-b666e0914606)

INTRODUCTION (#u2676c614-495e-5c17-9c1d-f66da8ad70cd)

OUTBACK AMBO – AUSTRALIA (#ud99971db-2085-58c7-9655-2ba0168ca4e3)

RUNNING WITH THE LEOPARD – SOUTH AFRICA (#ua0433f24-636f-5766-80a9-bb6886657cc7)

SHEIK, RATTLE AND ROLL – ENGLAND (#u06f620b6-4e17-5c99-b45b-ada2285b2fd8)

ALL QUIET! NEWS BULLETIN! – THE PHILIPPINES (#u9e869657-ff09-56c2-910c-320a1cce97d7)

DR AQUARIUS AND THE GYPSIES – MACEDONIA (#u2b2da4e4-0cb9-5277-a552-7b88131ba048)

ISLAND OF THE MONSTER WAVE – THAILAND (#litres_trial_promo)

A COUNTRY TO SAVE – PAKISTAN (#litres_trial_promo)

THE NAKED PARAMEDIC – ICELAND (#litres_trial_promo)

DEATH IN VENICE – ITALY (#litres_trial_promo)

A HULA SAVED MY LIFE – HAWAII (#litres_trial_promo)

THE CROSS OF FIRE – MEXICO (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

GLOSSARY (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

From the day of its invention the ambulance has attracted a magnetic curiosity from humans around the world. This vehicle racing to the scene of accidents and illness demands attention. When you hear one coming, you turn. When you watch it pass you wonder, if only for a moment, where it might be going, who is inside and what horrific mishap the patient has suffered. After fifteen years spent in the back of ambulances I’ve come to realise that medics and paramedics are endlessly fascinating to the public.

But despite our appeal, the truth about us is largely hidden from view. It is hidden because, in the instant we drive past we have carried our secrets away, leaving nothing more than the wail of a siren. We are hidden because the usual depiction of paramedics on film and television is mostly a fantasy. The title of hero is forced upon us, and what is lost is who we really are.

Right now, as you read this, more than a hundred thousand ambulance medics in all manner of unusual and remote locations across the planet are responding to emergencies. They are scrambling under crashed cars, carrying the sick down flights of stairs, scooping up body parts after bombings, comforting the depressed, resuscitating near-dead husbands at the feet of hysterical wives, and stemming the blood-flow of gunshot victims in seedy back alleys. A good number too are just as likely to be raising an eyebrow at some ridiculous, trivial complaint their patient has considered life-threatening. Each of these medics could fill a book just like this one, with adventures many more extreme, dangerous and shocking than those recounted here.

My fascination with the lives of people from countries and cultures other than my own is driven by my ultimate desire to understand humanity. And so I travel at every opportunity to observe how people interact, and learn why they believe what they do, how they live and how they die and how they grieve. From the age of nineteen, during periods of leave each year, I have worked or volunteered with foreign ambulance services. Whether acting as a guest or consultant, I stayed sometimes for a month, other times more than a year. Every day it has been a privilege. There are few professions like that of an ambulance worker – we have a rare licence to enter the homes of complete strangers and bear witness to their most personal moments of crisis.

Globally, the make-up of ambulance crews is varied, though it’s generally agreed there are two models of pre-hospital care delivery – the Anglo-American model based on one or two paramedics per ambulance, or the Franco-German model where the job is performed by doctors and nurses. Over recent years, a number of Anglo-American systems have also introduced paramedic practitioners with skills that, until now, have been the strict domain of emergency physicians. Pre-hospital worker profiles also include drivers and untrained attendants who can still be found responding in basic transport ambulances across many developing countries. Since cases demanding advanced medical intervention represent only a small percentage of emergency calls, it would be a mistake to judge ambulance workers as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ solely on clinical ability. Consequently, I have chosen to explore the world of many ambulance workers, no matter where they are from or what their qualifications. It is true that ambulance medics are united by the unique challenges of their job. They are members of a giant family and they understand one another instantly. While the work may differ in its frequency, level of drama and cultural peculiarities, there is no doubt that medics the world over experience similar thrills and nightmares.

As a paramedic and traveller, I’ve enjoyed the company of my brothers and sisters in many exotic locations. I’ve lived with them, laughed with them and cried with them. And wherever it was I journeyed, my ambulance family not only showed me their way of life, they also unlocked for me the secret doors to their cities and the character of their people, convincing me that paramedics are the best travel guides one can hope to have.

More than a story about the sick and injured, Paramédico is about the places where I have worked and the people I have worked there with. It’s about the men and women who have remained a mystery to the world for long enough.

So, climb aboard, buckle up, and embark with me on these grand adventures by ambulance.

OUTBACK AMBO

Australia

For two weeks I have sat here in this fibro shack along the Newell Highway listening to the ceaseless drone of air-conditioning, waiting for the sick and injured to call me. Coursework for my paramedic degree is done and all my novels are read. Now I wait, occasionally wishing, with guilt, for some drama to occur, some crisis, no matter how small, anything to break the monotony of my posting.

From time to time my mother sends me a letter or her ginger cake wrapped in brown paper. For the second time today, I drive to the post office in my ambulance.

I’m stationed in Peak Hill in central New South Wales, a town some locals might consider their whole world. But to me, a nineteen-year-old city boy with an interest in surfing and clubbing, I am cast away, marooned, washed up in the stinking hot Australian outback.

‘Sorry, champ,’ says the post officer. ‘Nothing today.’

And so I drive my ambulance around the handful of quiet streets where nothing ever changes, where I rarely see a soul. Shutters are down, curtains drawn, doors shut. Where are they all, I wonder, these people who apparently know my every move?

I turn down towards the wheat silo and park, imagining how I would treat someone who had fallen from the top of it. After that I go to meet a flock of sheep with whom I’ve learnt to communicate. Much of it is non-verbal. We just stand there, the flock and I, face to face, staring quietly, contemplating what the other’s life must be like. Now and then we exchange simple sounds by way of call-and-response. Whenever I think I’ve gone mad I remind myself that most people talk freely to their pets without a second thought.

Earlier in the year, the Ambulance Service of New South Wales sent my whole class to remote corners of the state. I understood, of course, that in our vast country with its sparsely populated interior, everyone is equally entitled to pre-hospital care. Only problem is that few applications to the service are received from people living in the bush. Instead, young, degree-qualified city recruits from the eastern seaboard end up in one-horse towns.

As I entered the Club House Hotel in Caswell Street on my first night, twelve faces textured like the Harvey Ranges turned my way, looked me up and down taking in my stovepipe jeans, my combed hair and patterned shirt. As if my appearance was not out of place enough, I foolishly ordered a middy of Victoria Bitter and the room erupted in thigh-slapping laughter. Before I ran out, a walnut of a man nearest to me leant over to offer some local advice.

‘Out here, mate, it’s a schooner of Tooheys New, got it?’

I never went back to the pub, at least not socially. When called there in the ambulance for drunks fallen over, I was always greeted with the same row of men in the same position at the bar, like they had never gone home. It didn’t take me long to realise I’d need to find entertainment elsewhere.

In less than a month Kristy Wright, an actor playing the role of Chloe Richards on the evening soap Home & Away, has become the object of my affection. As the elderly will attest, a routine of the ordinary brings security of sorts, a familiar comfort, and Home & Away is just this for a lonely paramedic with too much time on his hands and not enough human company. Kristy is not particularly glamorous, nor is she Oscar material. Perhaps it’s her likeness to my first proper girlfriend, a ballerina who ran off to Queensland, married someone else, and broke my heart. Whatever the reason, I’m deeply smitten and make sure never to miss an episode.

For a small fee I have taken accommodation in the nurses’ quarters on the grounds of Peak Hill’s tiny brick hospital with its single emergency bed. Adjacent to the hospital lies the ambulance station consisting of a small office, a portable shed with air-conditioning and a garage containing an F100 and a Toyota 4x4 ambulance for difficult terrain. My new home next door is a freestanding weatherboard cottage, a little rundown but quaint nonetheless. Lodging at these nurses’ quarters initially sounded quite appealing to a young, single man, but the place never came with any nurses in it.

At 8 pm I ladle some lentil soup out of a giant pot I prepared earlier in the week, heating it up on the electric stove. After dinner, at 9 pm, I run the bath, making sure my blue fire-resistant jumpsuit is hanging by the door and my boots are standing to attention below, ready for the next job – if I ever live to see it, that is. Two slow weeks and I’m beginning to think they should close the ambulance station down before their assets rust away. The population plummeted a few years ago when Peak Hill’s gold mine hit the water table and ceased operations. Locals left behind would disagree, but maybe ambulance stations ought to come and go with the mines.

Benjamin Gilmour

Around the world by ambulance.Paramédico is a brilliant collection of adventures by Australian paramedic Benjamin Gilmour as he works and volunteers on ambulances around the world. From England to Mexico, and Iceland to Pakistan, Gilmour takes us on an extraordinary thrill-ride with his wild coworkers. Along the way he learns a few things, too, and shows us not only how precious life truly is, but how to passionately embrace it.

To the men, women and children working on ambulances around the world.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u50194e03-4df3-56da-b4aa-20568f8a29eb)

TITLE PAGE (#u28931fcb-8b44-5c9f-9a3e-86006f7eb664)

DEDICATION (#uca5b3bda-af55-509c-aecb-b666e0914606)

INTRODUCTION (#u2676c614-495e-5c17-9c1d-f66da8ad70cd)

OUTBACK AMBO – AUSTRALIA (#ud99971db-2085-58c7-9655-2ba0168ca4e3)

RUNNING WITH THE LEOPARD – SOUTH AFRICA (#ua0433f24-636f-5766-80a9-bb6886657cc7)

SHEIK, RATTLE AND ROLL – ENGLAND (#u06f620b6-4e17-5c99-b45b-ada2285b2fd8)

ALL QUIET! NEWS BULLETIN! – THE PHILIPPINES (#u9e869657-ff09-56c2-910c-320a1cce97d7)

DR AQUARIUS AND THE GYPSIES – MACEDONIA (#u2b2da4e4-0cb9-5277-a552-7b88131ba048)

ISLAND OF THE MONSTER WAVE – THAILAND (#litres_trial_promo)

A COUNTRY TO SAVE – PAKISTAN (#litres_trial_promo)

THE NAKED PARAMEDIC – ICELAND (#litres_trial_promo)

DEATH IN VENICE – ITALY (#litres_trial_promo)

A HULA SAVED MY LIFE – HAWAII (#litres_trial_promo)

THE CROSS OF FIRE – MEXICO (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

GLOSSARY (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

From the day of its invention the ambulance has attracted a magnetic curiosity from humans around the world. This vehicle racing to the scene of accidents and illness demands attention. When you hear one coming, you turn. When you watch it pass you wonder, if only for a moment, where it might be going, who is inside and what horrific mishap the patient has suffered. After fifteen years spent in the back of ambulances I’ve come to realise that medics and paramedics are endlessly fascinating to the public.

But despite our appeal, the truth about us is largely hidden from view. It is hidden because, in the instant we drive past we have carried our secrets away, leaving nothing more than the wail of a siren. We are hidden because the usual depiction of paramedics on film and television is mostly a fantasy. The title of hero is forced upon us, and what is lost is who we really are.

Right now, as you read this, more than a hundred thousand ambulance medics in all manner of unusual and remote locations across the planet are responding to emergencies. They are scrambling under crashed cars, carrying the sick down flights of stairs, scooping up body parts after bombings, comforting the depressed, resuscitating near-dead husbands at the feet of hysterical wives, and stemming the blood-flow of gunshot victims in seedy back alleys. A good number too are just as likely to be raising an eyebrow at some ridiculous, trivial complaint their patient has considered life-threatening. Each of these medics could fill a book just like this one, with adventures many more extreme, dangerous and shocking than those recounted here.

My fascination with the lives of people from countries and cultures other than my own is driven by my ultimate desire to understand humanity. And so I travel at every opportunity to observe how people interact, and learn why they believe what they do, how they live and how they die and how they grieve. From the age of nineteen, during periods of leave each year, I have worked or volunteered with foreign ambulance services. Whether acting as a guest or consultant, I stayed sometimes for a month, other times more than a year. Every day it has been a privilege. There are few professions like that of an ambulance worker – we have a rare licence to enter the homes of complete strangers and bear witness to their most personal moments of crisis.

Globally, the make-up of ambulance crews is varied, though it’s generally agreed there are two models of pre-hospital care delivery – the Anglo-American model based on one or two paramedics per ambulance, or the Franco-German model where the job is performed by doctors and nurses. Over recent years, a number of Anglo-American systems have also introduced paramedic practitioners with skills that, until now, have been the strict domain of emergency physicians. Pre-hospital worker profiles also include drivers and untrained attendants who can still be found responding in basic transport ambulances across many developing countries. Since cases demanding advanced medical intervention represent only a small percentage of emergency calls, it would be a mistake to judge ambulance workers as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ solely on clinical ability. Consequently, I have chosen to explore the world of many ambulance workers, no matter where they are from or what their qualifications. It is true that ambulance medics are united by the unique challenges of their job. They are members of a giant family and they understand one another instantly. While the work may differ in its frequency, level of drama and cultural peculiarities, there is no doubt that medics the world over experience similar thrills and nightmares.

As a paramedic and traveller, I’ve enjoyed the company of my brothers and sisters in many exotic locations. I’ve lived with them, laughed with them and cried with them. And wherever it was I journeyed, my ambulance family not only showed me their way of life, they also unlocked for me the secret doors to their cities and the character of their people, convincing me that paramedics are the best travel guides one can hope to have.

More than a story about the sick and injured, Paramédico is about the places where I have worked and the people I have worked there with. It’s about the men and women who have remained a mystery to the world for long enough.

So, climb aboard, buckle up, and embark with me on these grand adventures by ambulance.

OUTBACK AMBO

Australia

For two weeks I have sat here in this fibro shack along the Newell Highway listening to the ceaseless drone of air-conditioning, waiting for the sick and injured to call me. Coursework for my paramedic degree is done and all my novels are read. Now I wait, occasionally wishing, with guilt, for some drama to occur, some crisis, no matter how small, anything to break the monotony of my posting.

From time to time my mother sends me a letter or her ginger cake wrapped in brown paper. For the second time today, I drive to the post office in my ambulance.

I’m stationed in Peak Hill in central New South Wales, a town some locals might consider their whole world. But to me, a nineteen-year-old city boy with an interest in surfing and clubbing, I am cast away, marooned, washed up in the stinking hot Australian outback.

‘Sorry, champ,’ says the post officer. ‘Nothing today.’

And so I drive my ambulance around the handful of quiet streets where nothing ever changes, where I rarely see a soul. Shutters are down, curtains drawn, doors shut. Where are they all, I wonder, these people who apparently know my every move?

I turn down towards the wheat silo and park, imagining how I would treat someone who had fallen from the top of it. After that I go to meet a flock of sheep with whom I’ve learnt to communicate. Much of it is non-verbal. We just stand there, the flock and I, face to face, staring quietly, contemplating what the other’s life must be like. Now and then we exchange simple sounds by way of call-and-response. Whenever I think I’ve gone mad I remind myself that most people talk freely to their pets without a second thought.

Earlier in the year, the Ambulance Service of New South Wales sent my whole class to remote corners of the state. I understood, of course, that in our vast country with its sparsely populated interior, everyone is equally entitled to pre-hospital care. Only problem is that few applications to the service are received from people living in the bush. Instead, young, degree-qualified city recruits from the eastern seaboard end up in one-horse towns.

As I entered the Club House Hotel in Caswell Street on my first night, twelve faces textured like the Harvey Ranges turned my way, looked me up and down taking in my stovepipe jeans, my combed hair and patterned shirt. As if my appearance was not out of place enough, I foolishly ordered a middy of Victoria Bitter and the room erupted in thigh-slapping laughter. Before I ran out, a walnut of a man nearest to me leant over to offer some local advice.

‘Out here, mate, it’s a schooner of Tooheys New, got it?’

I never went back to the pub, at least not socially. When called there in the ambulance for drunks fallen over, I was always greeted with the same row of men in the same position at the bar, like they had never gone home. It didn’t take me long to realise I’d need to find entertainment elsewhere.

In less than a month Kristy Wright, an actor playing the role of Chloe Richards on the evening soap Home & Away, has become the object of my affection. As the elderly will attest, a routine of the ordinary brings security of sorts, a familiar comfort, and Home & Away is just this for a lonely paramedic with too much time on his hands and not enough human company. Kristy is not particularly glamorous, nor is she Oscar material. Perhaps it’s her likeness to my first proper girlfriend, a ballerina who ran off to Queensland, married someone else, and broke my heart. Whatever the reason, I’m deeply smitten and make sure never to miss an episode.

For a small fee I have taken accommodation in the nurses’ quarters on the grounds of Peak Hill’s tiny brick hospital with its single emergency bed. Adjacent to the hospital lies the ambulance station consisting of a small office, a portable shed with air-conditioning and a garage containing an F100 and a Toyota 4x4 ambulance for difficult terrain. My new home next door is a freestanding weatherboard cottage, a little rundown but quaint nonetheless. Lodging at these nurses’ quarters initially sounded quite appealing to a young, single man, but the place never came with any nurses in it.

At 8 pm I ladle some lentil soup out of a giant pot I prepared earlier in the week, heating it up on the electric stove. After dinner, at 9 pm, I run the bath, making sure my blue fire-resistant jumpsuit is hanging by the door and my boots are standing to attention below, ready for the next job – if I ever live to see it, that is. Two slow weeks and I’m beginning to think they should close the ambulance station down before their assets rust away. The population plummeted a few years ago when Peak Hill’s gold mine hit the water table and ceased operations. Locals left behind would disagree, but maybe ambulance stations ought to come and go with the mines.