По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

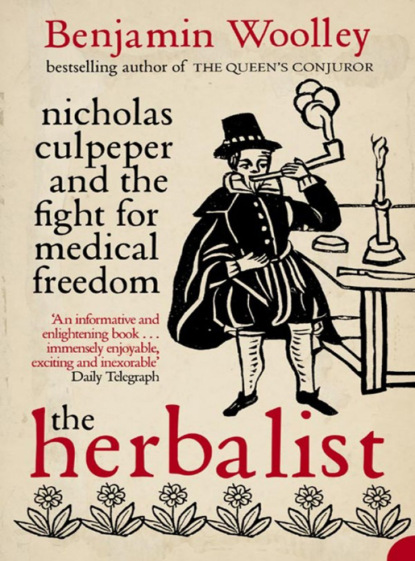

The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom

Benjamin Woolley

From the bestselling author of ‘The Queen’s Conjuror’, comes the story of Nicholas Culpeper – legendary rebel, radical, Puritan, and author of the great ‘Herbal’. This is a powerful history of medicine’s first freedom fighter set in London during Britain’s age of revolution.In the mid-17th century, England was visited by the four horsemen of the apocalypse: a civil war which saw levels of slaughter not matched until the Somme, famine in a succession of failed harvests that reduced peasants to 'anatomies', epidemics to rival the Black Death in their enormity, and infant mortality rates that left childless even women who had borne eight or nine children. In the midst of these terrible times came Nicholas Culpeper’s ‘Herbal’ – one of the most popular and enduring books ever published.Culpeper was a virtual outcast from birth. Rebelling against a tyrannical grandfather and the prospect of a life in the church, he abandoned his university education after a doomed attempt at elopement. Disinherited, he went to London, where he was to find his vocation in instigating revolution.London's medical regime was then in the grip of the College of Physicians, a powerful body personified in the ‘immortal’ William Harvey, anatomist, royal physician and discoverer of the circulation of the blood. Working in the underground world of religious sects, secret printing presses and unlicensed apothecary shops, Culpeper challenged this stronghold at the time it was reaching the very pinnacle of its power – and in the process helped spark the revolution that toppled a monarchy.In a spellbinding narrative of impulse, romance and heroism, Benjamin Woolley vividly recreates these momentous struggles and the roots of today's hopes and fears about the power of medical science, professional institutions and government. ‘The Herbalist’ tells the story of a medical rebel who took on the authorities and paid the price.

THE HERBALIST

Nicholas Culpeper and the fight for medical freedom

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY

DEDICATION (#ulink_d817619b-e569-589b-a668-b885d70a211e)

In memory of Joy Woolley,

1921–2003

PREFACE (#ulink_1422a78c-2d36-555d-a5d6-adfca9996bcc)

In the landscape of history, Nicholas Culpeper has not always been welcome. If monarchs, ministers, political notables and scientific luminaries are stately oaks or cultivated blooms, Culpeper is the Cleavers (or Goosegrass, or Barweed, or Hedgeheriff, or Hayruff, or Mutton Chops, or Robin-Run-in-the-Grass, to use any of its multitude of names), a common grass that is ‘so troublesome an Inhabitant in Gardens’, creeping into the herbaceous borders and snagging clothes. As a result, he has been weeded out of the historical record, and barely a trace of him is left. The only documentation relating to him that survives is a brief memoir, one letter, a couple of manuscript fragments, several tantalising mentions in official papers, and some pamphlets. His own voluminous writings brim with character, but are almost empty of biographical details. Official medical and botanical histories written while he lived and since have contributed nothing, and in some cases have taken a great deal away. For this reason, Nicholas’s presence in history, and in the account that follows, is necessarily fleeting.

However, hidden in the undergrowth is a startling story, entangled with so many others, with the struggles of the woodturner Nehemiah Wallington to survive the plague, with the mischievous prophesies of the astrologer William Lilly, with the Olympian struggles and self-belief of King Charles I, and most of all with the anatomical explorations and loyal ministrations of the King’s doctor William Harvey, the Isaac Newton of medical science and model of medical professionalism. Like the Cleavers and other discarded weeds championed in his Herbal, Nicholas certainly had ‘some Vices [but] also many Virtues’. His vices were well known, itemised by friends as well as his many enemies: smoking, drinking, ‘consumption of the purse’. But he was also audacious and adventurous. He championed the poor and sick at a time when they were more vulnerable than ever. He took on an establishment fighting for survival and ferociously intent on preserving its privileges.

The heirs of that same establishment are inevitably the custodians of much of the material upon which this book relies, in particular the Royal College of Physicians, which provided generous access to its archives. Acknowledgement must also go to the Society of Apothecaries, the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the Cambridge University Library, the Records Offices of the counties of East and West Sussex, Kent, Surrey, and of London, primarily the Guildhall Library, the Corporation of London and the Metropolitan Archives. Individual thanks are due to Briony Thomas and the Revd Roger Dalling for local information on Nicholas’s childhood, to Dr Jonathan Wright for reading the manuscript and Dr Adrian Mathie for checking some of the medical information.

The dates given are new style unless otherwise stated. Spelling and punctuation have been modernised where appropriate. Notes at the back provide details on sources, clarifications and definitions of some of the medical and astrological terminology, and brief discussions of the historical evidence. One final note: the capitalised ‘City’ refers to the square mile that is the formally recognised city of London, a distinct political as well as urban entity with its own government and privileges, lying within the bounds of the ancient city walls. ‘London’ or the ‘city’ refers to the wider metropolitan area, embracing the city of Westminster to the west, Southwark on the south bank of the Thames, and the sprawling suburbs to the north and east.

CONTENTS

Cover (#ua2a0a718-7322-52e0-9633-c4f0b2b5c58d)

Title Page (#u5ec5ffca-1114-5ab0-a4ce-f80627f86a26)

Dedication (#u178cf9d1-5a0a-51ba-98ab-0575264bf82c)

Preface (#ud67f886d-1503-59f9-bd41-a2ba5c7bbf1f)

Tansy: Tanacetum vulgare (#ud0d2b959-d3a2-59ed-bc39-b5251a9fd1d3)

Borage: Borago officinalis (#uc5616f3d-654a-58fb-ba58-bab0ce3a511a)

Angelica: Angelica archangelica (#u528ba62b-9272-56eb-acf8-3aae8deb03d4)

Balm: Melissa officinalis (#litres_trial_promo)

Melancholy Thistle: Carduus heterophyllus (#litres_trial_promo)

Self-Heal: Prunella vulgaris (#litres_trial_promo)

Rosa Solis, or Sun-Dew: Drosera rotundifolia (#litres_trial_promo)

Bryony, or Wild Vine: Bryonia dioica (#litres_trial_promo)

Hemlock: Conium maculatum (#litres_trial_promo)

Lesser Celandine (Pilewort): Ranunculus ficaria (#litres_trial_promo)

Arrach Wild & Stinking: Atriplex hortensis, olida (#litres_trial_promo)

Wormwood: Artemisia absinthium/pontica (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

TANSY (#ulink_275ce703-093b-5008-85d0-b24a3a67f0e0)

Tanacetum vulgare (#ulink_275ce703-093b-5008-85d0-b24a3a67f0e0)

Dame Venus was minded to pleasure Women with Child by this Herb, for there grows not an Herb fitter for their uses than this is, it is just as though it were cut out for the purpose. The Herb bruised and applied to the Navel stays miscarriage, I know no Herb like it for that use. Boiled in ordinary Beer, and the Decoction drunk, doth the like, and if her Womb be not as she would have, this Decoction will make it as she would have it, or at least as she should have it.

Let those Women that desire Children love this Herb, ’tis their best Companion, their Husband excepted.

The Herb fried with Eggs (as is accustomed in the Spring time) which is called a Tansy, helpeth to digest, and carry downward those bad Humours that trouble the Stomach: The Seed is very profitably given to Children for the Worms, and the Juice in Drink is as effectual. Being boiled in Oil it is good for the sinews shrunk by Cramps, or pained with cold, if thereto applied.

Also it consumes the Phlegmatic Humours, the cold and moist constitution of Winter most usually infects the Body of Man with, and that was the first reason of eating Tansies in the Spring. At last the world being overrun with Popery, a Monster called Superstition perks up his head … and now forsooth Tansies must be eaten only on Palm and Easter Sundays, and their neighbour days; [the] Superstition of the time was found out, but the Virtue of the Herb hidden, and now ’tis almost, if not altogether, left off.*

Tansy has a tall, leafy stem, two or three feet high, with ferny foliage and flowers like golden buttons.

Benjamin Woolley

From the bestselling author of ‘The Queen’s Conjuror’, comes the story of Nicholas Culpeper – legendary rebel, radical, Puritan, and author of the great ‘Herbal’. This is a powerful history of medicine’s first freedom fighter set in London during Britain’s age of revolution.In the mid-17th century, England was visited by the four horsemen of the apocalypse: a civil war which saw levels of slaughter not matched until the Somme, famine in a succession of failed harvests that reduced peasants to 'anatomies', epidemics to rival the Black Death in their enormity, and infant mortality rates that left childless even women who had borne eight or nine children. In the midst of these terrible times came Nicholas Culpeper’s ‘Herbal’ – one of the most popular and enduring books ever published.Culpeper was a virtual outcast from birth. Rebelling against a tyrannical grandfather and the prospect of a life in the church, he abandoned his university education after a doomed attempt at elopement. Disinherited, he went to London, where he was to find his vocation in instigating revolution.London's medical regime was then in the grip of the College of Physicians, a powerful body personified in the ‘immortal’ William Harvey, anatomist, royal physician and discoverer of the circulation of the blood. Working in the underground world of religious sects, secret printing presses and unlicensed apothecary shops, Culpeper challenged this stronghold at the time it was reaching the very pinnacle of its power – and in the process helped spark the revolution that toppled a monarchy.In a spellbinding narrative of impulse, romance and heroism, Benjamin Woolley vividly recreates these momentous struggles and the roots of today's hopes and fears about the power of medical science, professional institutions and government. ‘The Herbalist’ tells the story of a medical rebel who took on the authorities and paid the price.

THE HERBALIST

Nicholas Culpeper and the fight for medical freedom

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY

DEDICATION (#ulink_d817619b-e569-589b-a668-b885d70a211e)

In memory of Joy Woolley,

1921–2003

PREFACE (#ulink_1422a78c-2d36-555d-a5d6-adfca9996bcc)

In the landscape of history, Nicholas Culpeper has not always been welcome. If monarchs, ministers, political notables and scientific luminaries are stately oaks or cultivated blooms, Culpeper is the Cleavers (or Goosegrass, or Barweed, or Hedgeheriff, or Hayruff, or Mutton Chops, or Robin-Run-in-the-Grass, to use any of its multitude of names), a common grass that is ‘so troublesome an Inhabitant in Gardens’, creeping into the herbaceous borders and snagging clothes. As a result, he has been weeded out of the historical record, and barely a trace of him is left. The only documentation relating to him that survives is a brief memoir, one letter, a couple of manuscript fragments, several tantalising mentions in official papers, and some pamphlets. His own voluminous writings brim with character, but are almost empty of biographical details. Official medical and botanical histories written while he lived and since have contributed nothing, and in some cases have taken a great deal away. For this reason, Nicholas’s presence in history, and in the account that follows, is necessarily fleeting.

However, hidden in the undergrowth is a startling story, entangled with so many others, with the struggles of the woodturner Nehemiah Wallington to survive the plague, with the mischievous prophesies of the astrologer William Lilly, with the Olympian struggles and self-belief of King Charles I, and most of all with the anatomical explorations and loyal ministrations of the King’s doctor William Harvey, the Isaac Newton of medical science and model of medical professionalism. Like the Cleavers and other discarded weeds championed in his Herbal, Nicholas certainly had ‘some Vices [but] also many Virtues’. His vices were well known, itemised by friends as well as his many enemies: smoking, drinking, ‘consumption of the purse’. But he was also audacious and adventurous. He championed the poor and sick at a time when they were more vulnerable than ever. He took on an establishment fighting for survival and ferociously intent on preserving its privileges.

The heirs of that same establishment are inevitably the custodians of much of the material upon which this book relies, in particular the Royal College of Physicians, which provided generous access to its archives. Acknowledgement must also go to the Society of Apothecaries, the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the Cambridge University Library, the Records Offices of the counties of East and West Sussex, Kent, Surrey, and of London, primarily the Guildhall Library, the Corporation of London and the Metropolitan Archives. Individual thanks are due to Briony Thomas and the Revd Roger Dalling for local information on Nicholas’s childhood, to Dr Jonathan Wright for reading the manuscript and Dr Adrian Mathie for checking some of the medical information.

The dates given are new style unless otherwise stated. Spelling and punctuation have been modernised where appropriate. Notes at the back provide details on sources, clarifications and definitions of some of the medical and astrological terminology, and brief discussions of the historical evidence. One final note: the capitalised ‘City’ refers to the square mile that is the formally recognised city of London, a distinct political as well as urban entity with its own government and privileges, lying within the bounds of the ancient city walls. ‘London’ or the ‘city’ refers to the wider metropolitan area, embracing the city of Westminster to the west, Southwark on the south bank of the Thames, and the sprawling suburbs to the north and east.

CONTENTS

Cover (#ua2a0a718-7322-52e0-9633-c4f0b2b5c58d)

Title Page (#u5ec5ffca-1114-5ab0-a4ce-f80627f86a26)

Dedication (#u178cf9d1-5a0a-51ba-98ab-0575264bf82c)

Preface (#ud67f886d-1503-59f9-bd41-a2ba5c7bbf1f)

Tansy: Tanacetum vulgare (#ud0d2b959-d3a2-59ed-bc39-b5251a9fd1d3)

Borage: Borago officinalis (#uc5616f3d-654a-58fb-ba58-bab0ce3a511a)

Angelica: Angelica archangelica (#u528ba62b-9272-56eb-acf8-3aae8deb03d4)

Balm: Melissa officinalis (#litres_trial_promo)

Melancholy Thistle: Carduus heterophyllus (#litres_trial_promo)

Self-Heal: Prunella vulgaris (#litres_trial_promo)

Rosa Solis, or Sun-Dew: Drosera rotundifolia (#litres_trial_promo)

Bryony, or Wild Vine: Bryonia dioica (#litres_trial_promo)

Hemlock: Conium maculatum (#litres_trial_promo)

Lesser Celandine (Pilewort): Ranunculus ficaria (#litres_trial_promo)

Arrach Wild & Stinking: Atriplex hortensis, olida (#litres_trial_promo)

Wormwood: Artemisia absinthium/pontica (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

TANSY (#ulink_275ce703-093b-5008-85d0-b24a3a67f0e0)

Tanacetum vulgare (#ulink_275ce703-093b-5008-85d0-b24a3a67f0e0)

Dame Venus was minded to pleasure Women with Child by this Herb, for there grows not an Herb fitter for their uses than this is, it is just as though it were cut out for the purpose. The Herb bruised and applied to the Navel stays miscarriage, I know no Herb like it for that use. Boiled in ordinary Beer, and the Decoction drunk, doth the like, and if her Womb be not as she would have, this Decoction will make it as she would have it, or at least as she should have it.

Let those Women that desire Children love this Herb, ’tis their best Companion, their Husband excepted.

The Herb fried with Eggs (as is accustomed in the Spring time) which is called a Tansy, helpeth to digest, and carry downward those bad Humours that trouble the Stomach: The Seed is very profitably given to Children for the Worms, and the Juice in Drink is as effectual. Being boiled in Oil it is good for the sinews shrunk by Cramps, or pained with cold, if thereto applied.

Also it consumes the Phlegmatic Humours, the cold and moist constitution of Winter most usually infects the Body of Man with, and that was the first reason of eating Tansies in the Spring. At last the world being overrun with Popery, a Monster called Superstition perks up his head … and now forsooth Tansies must be eaten only on Palm and Easter Sundays, and their neighbour days; [the] Superstition of the time was found out, but the Virtue of the Herb hidden, and now ’tis almost, if not altogether, left off.*

Tansy has a tall, leafy stem, two or three feet high, with ferny foliage and flowers like golden buttons.