По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

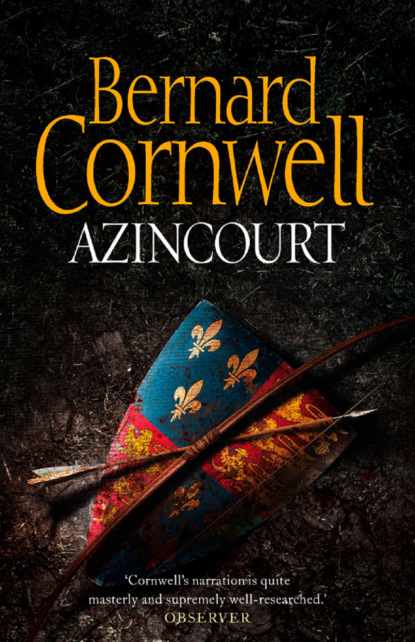

Azincourt

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’ve an inkling she don’t care one way or the other,’ Wilkinson said. He was pulling on a mail coat, struggling to get the heavy links over his head. ‘There’s an arrow bag by the door,’ he went on, his voice now muffled by the coat, ‘full of straight ones. Left it for you. Go, boy, kill some bastards.’

‘What about you?’ Hook asked. He was tugging on his boots, new boots made by a skilled cobbler of Soissons.

‘I’ll catch up with you! String your bow, son, and go!’

Hook buckled his sword belt, strung his bow, snatched his arrow bag, then took the second bag from beside the door and ran into the tavern yard. He could hear shouting and screams, but where they came from he could not tell. Archers were pouring into the yard and he instinctively followed them towards the new defences behind the breach. The church bells were hammering the night sky with jangling noise. Dogs barked and howled.

Hook had no armour except for an ancient helmet that Wilkinson had given him and which sat on his head like a bowl. He had a padded jacket that might stop a feeble sword swing, but that was his only protection. Other archers had short mail coats and close-fitting helmets, but they all wore Burgundy’s brief surcoat blazoned with the jagged red cross and Hook saw those liveries lining the new wall that was made of wicker baskets filled with earth. None of the archers was drawing a cord yet, instead they just looked towards the breach that flared with sudden light as Burgundian men-at-arms threw pitch-soaked torches into the gap of the gun-ravaged wall.

There were close to fifty men-at-arms at the new wall, but no enemy in the breach. Yet the bells still rang frantically to announce a French attack, and Hook swung around to see a glow in the sky above the city’s southern rooftops, a glow that flickered lurid on the cathedral’s tower as evidence that buildings burned somewhere near the Paris gate. Was that where the French attacked? The Paris gate was commanded by Sir Roger Pallaire and defended by the English men-at-arms and Hook wondered, not for the first time, why Sir Roger had not demanded that the English archers join that gate’s garrison.

Instead the archers waited by the western breach where still no enemy appeared. Smithson, the centenar, was nervous. He kept fingering the silver chain that denoted his rank and glancing towards the glow of the southern fires, then back to the breach. ‘Devil’s turd,’ he said of no one in particular.

‘What’s happening?’ an archer demanded.

‘How in God’s name would I know?’ Smithson snarled.

‘I think they’re already inside the city,’ John Wilkinson said mildly. He had brought a dozen sheaves of spare arrows that he now dropped behind the archers. The sound of screams came from somewhere in the city and a troop of Burgundian crossbowmen ran past Hook, abandoning the breach and heading towards the Paris gate. Some of the men-at-arms followed them.

‘If they’re inside the town,’ Smithson said uncertainly, ‘then we should go to the church.’

‘Not to the castle?’ a man demanded.

‘We go to the church, I think,’ Smithson said, ‘as Sir Roger says. He’s gentry, isn’t he? He must know what he’s doing.’

‘Aye, and the Pope lays eggs,’ Wilkinson commented.

‘Now?’ a man asked, ‘we go now?’ but Smithson said nothing. He just tugged at the silver chain and looked left and right.

Hook was staring at the breach. His heart was beating hard, his breathing was shallow and his right leg trembled. ‘Help me, God,’ he prayed, ‘sweet Jesu protect me,’ but he got no comfort from the prayer. All he could think of was that the enemy was in Soissons, or attacking Soissons and he did not know what was happening and he felt vulnerable and helpless. The bells banged inside his head, confusing him. The wide breach was dark except for the feeble flicker of dying flames from the torches, but slowly Hook became aware of other lights moving there, of shifting silver-grey lights, lights like smoke in moonlight or like the ghosts who came to earth on Allhallows Eve. The lights, Hook thought, were beautiful; they were filmy and vaporous in the darkness. He stared, wondering what the glowing shapes were, and then the silver-grey wraiths turned to red and he realised, with a start of fear, that the shifting shapes were men. He was seeing the light of the torches reflected from plate armour. ‘Sergeant!’ he shouted.

‘What is it?’ Smithson snapped back.

‘The bastards are here!’ Hook called, and so they were. The bastards were coming through the breach. Their plate armour was scoured bright enough to reflect the firelight and they were advancing beneath a banner of blue on which golden lilies blossomed. Their visors were closed and their long swords flashed back the flame-light. They were no longer vaporous, now they resembled men of burning metal, phantoms from the dreams of hell, death coming through the dark to Soissons. Hook could not count them, they were so many.

‘Oh my God’s shit,’ Smithson said in panic, ‘stop them!’

Hook did what he was told. He stepped back to the barricade, plucked an arrow from the linen bag and laid it on the bow’s stave. The fear was suddenly gone, or else had been pushed aside by the certain knowledge of what needed to be done. Hook needed to haul back the bow’s cord.

Most grown men in the prime of their strength could not pull a war bow’s cord back to the ear. Most men-at-arms, despite being toughened by war and hardened by constant sword exercises, could only draw the hemp cord halfway, but Hook made it look easy. His arm flowed back, his eyes sought a mark for the arrow’s bright head and he did not even think as he released. He was already reaching for the second arrow as the first, a shaft-weighted bodkin, slapped through a breastplate of shining steel and threw the man back onto the French standard-bearer.

And Hook loosed again, not thinking, only knowing that he had been told to stop this attack. He loosed shaft after shaft. He drew the cord to his right ear and was not aware of the tiny shifts his left hand made to send the white-feathered arrows on their short journey from cord to victim. He was not aware of the deaths he caused or the injuries he gave or of the arrows that glanced off armour to spin uselessly away. Most were not useless. The long bodkin heads could easily punch through armour at this close range and Hook was stronger than most archers, who were stronger than most men, and his bow was heavy. John Wilkinson, when he had first met Hook, had drawn the younger man’s bow and failed to get the cord past his chin, and he had given Hook a glance of respect, and now that long, thick-bellied bow cut from the trunk of a yew in far-off Savoy, was sending death through the bell-ringing dark, except that Hook was only seeing the enemy who came across the breach where the guttering torches burned, and he did not notice the dark floods of men who surged at either edge of the wall’s gap and who were already tugging at the wicker baskets. Then part of the barricade collapsed and the noise made Hook turn to see that he was the only archer left at the defences. The breach, despite the dead who lay there and the injured who crawled there, was filled with howling men. The night was lit by fire, flame red, riddled with smoke and loud with war-shouts. Hook realised then that John Wilkinson had shouted at him to run, but in the moment’s excitement, the warning had not lodged in Hook’s mind.

But now it did. He plucked up the arrow bag and ran.

Men howled behind him as the barricade fell and the French swarmed across its remnants and into the city.

Hook understood then how the deer felt when the hounds were in every thicket and men were beating the undergrowth and arrows were whickering through the leaves. He had often wondered if an animal could know what death was. They knew fear, and they knew defiance, but beyond fear and defiance came the gut-emptying panic, the last moments of life as the hunters close in and the heart races and the mind slithers frantically. Hook felt that panic and ran. At first he just ran. The bells were still crashing, dogs were howling, men were roaring war-shouts and horns were calling. He ran into a small square, a space where leather merchants usually displayed their hides, and it was oddly deserted, but then he heard the sounds of bolts being shot and he understood that folk were hiding in their houses and barring their doors. Crashes announced where soldiers were kicking or beating those locked doors down. Go to the castle, he thought, and he ran that way, but turned a corner to see the wide space in front of the cathedral filled with men in unfamiliar liveries, their surcoats lit by the torches they carried, and he doubled back like a deer recoiling from hounds. He decided to go to Saint Antoine-le-Petit’s church and sprinted down an alley, twisted into another, ran across the open space in front of the city’s biggest nunnery, then turned down the street where the Goose tavern stood and saw still more men in their strange liveries, and those men blocked his way to the church. They spotted him and a growl sounded, and the growl turned into a triumphant howl as they ran towards him, and Hook, desperate as any doomed animal, bolted into an alley, leaped at the wall that blocked the end, sprawled over into a small yard that stank of sewage, scrambled across a second wall and then, surrounded by shouts and quivering with fear he sank into a dark corner and waited for the end.

A hunted deer would do that. When it saw no escape it would freeze, shiver and wait for the death it must sense. Now Hook shivered. Better to kill yourself, John Wilkinson had said, than be caught by the French and so Hook felt for his knife, but he could not draw it. He could not kill himself, and so he waited to be killed.

Then he realised his pursuers had evidently abandoned the chase. There was so much plunder for them in Soissons and so many victims, that one fugitive did not interest them and Hook, slowly recovering his senses, realised he had found a temporary refuge. He was in one of the Goose’s back yards, a place where the brewery barrels were washed and repaired. A door of the tavern suddenly opened and a flaming torch illuminated the trestles and staves and tuns. A man peered into the yard, said something dismissive and went back into the tavern where a woman screamed.

Hook stayed where he was. He dared not move. The city was full of women screaming now, full of hoarse male laughter and full of crying children. A cat stalked past him. The church bells had long ceased their clangour. He knew he could not stay where he was. Dawn would reveal him. Oh God, oh God, oh God, he prayed, unaware that he prayed. Be with me now and at the hour of my death. He shivered. Hooves sounded in the street beyond the brewery yard wall, a man laughed. A woman whimpered. Clouds scurried across the moon’s face and for some reason Hook thought of the badgers on Beggar’s Hill, and that homely thought calmed the panic.

He stood. Perhaps there was a chance he could reach the church? It was much closer than the castle, and Sir Roger had promised to make an attempt to save the archers’ lives, and, though it seemed a slender hope, it was all Hook could think of doing and so he pulled himself up the yard’s wall to peer over the top. The Goose’s stables were next door. No noise came from them and so he climbed onto the wall and from there he could step onto the stable roof that trembled under his weight, but by staying on the rooftop, where the ridge beam ran, he could shuffle until he reached the farther gable where he dropped into a dark alley. He was shaking again, knowing he was more vulnerable here. He moved silently, slowly, until he could peer about the alley’s corner to where the church lay.

And he saw there was no escape.

The church of Saint Antoine-le-Petit was guarded by enemies. There were over thirty men-at-arms and a dozen crossbowmen in the open space in front of the church steps, all in liveries that Hook had not seen before. If Smithson and the archers were inside the church then they were safe enough, for they could defend the door, but it seemed plain to Hook that the enemy must be there to prevent any archer escaping and, he assumed, they would stop any stray archer trying to approach the church. He thought of running for the doorway, but guessed it would be locked and that, while he was beating on the heavy timber, the crossbowmen would use him for a target.

The enemy was not just guarding the church. They had fetched barrels from some tavern and were drinking, and they had stripped two girls naked and tied them across the two barrels with their legs spread wide, and now the men took it in turns to hitch up their mail coats and rape the girls who lay silent as if they had been emptied of moans and tears. The city was loud with women screaming, and the sound scored across Hook’s conscience like an arrowhead scraping on slate, and perhaps that was why he did not move, but instead stood at the corner like an animal that had no place to run or hide. Hook wondered if the girls were dead, they were so still, but then the nearest turned her head and Hook remembered Sarah and flinched with guilt. The girl, who looked no older than twelve or thirteen, stared dully into the dark as a man jerked and grunted at her.

Then a door opened onto the alley and a flood of light washed across Hook who turned to see a man-at-arms stagger into the mud. The man wore a surcoat showing a silver wheat sheaf on a green field. The man fell to his knees and vomited as a second man, in the same livery, came to the door and laughed. It was that second man who saw Hook and recognised the great war bow, and so put his hand on his sword’s hilt.

Hook reacted in panic. He thrust the bow at the man with the sword. In his head he was screaming, unable to think, but the lunge had all his archer’s strength in it and the horn nock of the bow’s tip pierced the man-at-arms’s throat before his sword was even half drawn. Blood misted black and still Hook thrust so that the bow ripped clean through windpipe and muscle, skin and sinew to strike the doorjamb. The kneeling man was roaring, spraying vomit as he clawed at Hook who, still in panic, made a mewing noise of utter despair as he let go of the bow and thrust his hands at his new assailant. He felt his fingers crush eyeballs and the man began to scream, and Hook was dimly aware that the rapists outside the church were coming for him and he scrambled through the door, half tripping on the first man who lay trying to pull the bow from his ruptured throat as Hook ran across a room, burst through another door, down a passage, a third door, and he was in a yard, still not thinking, over a wall, a second wall, and there were shouts behind him and screams around him and he was in absolute terror now. He had lost his great yew bow, and had dropped the arrow bags, though he still had the sword every archer was expected to wear. He had never used it. He still wore the ragged red cross of Burgundy too, and he began to tear at the surcoat, trying to rid himself of the symbol as he looked desperately for an escape, any escape, then he scrambled over a stone wall into an alley shadowed by the overhanging houses, but in the dark he saw an open door and ran to it.

The door led into a large empty room where a guttering lantern showed a dead man sprawled across a cushioned wooden bench. The man’s blood had sheeted across the flagstones. A tapestry hung on one wall and there were cupboards and a long table holding an abacus and sheets of parchment that were speared on a tall spike. Hook reckoned the dead man must have been a merchant. In one corner a ladder climbed to a higher floor and Hook went up quickly to find a plastered chamber that held a wooden bed with a pallet and blankets. A second ladder led into the attic and he clambered up and pulled the ladder into the space beneath the rafters and cursed himself for not having done the same with the first ladder. Too late now. He dared not drop back into the house and so he crouched in the bat droppings beneath the thatch. He was still shaking. Men were shouting in the houses beneath him, and for a time it seemed he must be discovered, and that discovery seemed imminent when someone climbed into the room where the bed stood, but the man only glanced briefly about before leaving, and the rest of the searchers grew bored or else found other quarry, for after a while their excited shouting died. The screaming went on, indeed the screaming became louder and it seemed to Hook, listening in puzzlement, that a whole group of women were just outside the house, all shrieking, and he flinched at the sound. He thought of Sarah in London, of Sir Martin the priest, and of the men he had just seen who had looked so bored as they raped their two silent victims.

The screaming turned into sobbing, broken only by men’s laughter. Hook was shivering, not with cold, but with fear and guilt, and then he shrank into the small space under the sloping rafters because the room beneath was suddenly lit by a lantern. The light leaked through the attic’s crude floorboards that were loosely laid over untrimmed beams. A man had climbed into the room and was shouting down the ladder to other men, and then a woman cried and there was the sound of a slap.

‘You’re a pretty one,’ the man said, and Hook was so frightened that he did not even notice that the man spoke English.

‘Non,’ the woman whimpered.

‘Too pretty to share. You’re all mine, girl.’

Hook peered through a crack in the boards. He could see a wide-brimmed helmet that half obscured the man’s shoulders, and then he saw that the woman was a white-robed nun who crouched in a corner of the room. She was whimpering. ‘Jésus,’ she cried, ‘Marie, mère de Dieu!’ And the last word turned into a scream as the man drew a knife. ‘Non!’ she shouted. ‘Non! Non! Non!’ and the helmeted man slapped her hard enough to silence her as he pulled her upright. He put the knife at her neck, then slashed so that her habit was sliced down the front. He ripped the blade further and, despite her struggles, tore the white robe away from her and then cut at her undergarments. He threw her ruined clothes down to the lower floor and, when she was naked, pushed her onto the pallet where she curled into a ball and sobbed.

‘Oh, I’m sure God was delighted with that day’s work!’ the voice said, though no one spoke aloud because the voice was in Hook’s head. The words were those John Wilkinson had used to Hook in the cathedral, but the voice did not belong to the old archer. It was a richer, deeper voice, full of warmth, and Hook had a sudden vision of a white-robed man, smiling and carrying a tray heaped with pears and apples. It was Crispinian, the saint to whom he had addressed most of his prayers in Soissons, and now those prayers were being answered in Hook’s head, and in Hook’s head Crispinian looked sadly at him, and Hook understood that heaven had given him a chance to make amends. The nun in the room below had cried to Christ’s mother, and the Virgin must have spoken to the saints of Soissons who now spoke to Hook, but Hook was frightened. He was hearing voices again. He did not know it, but he was kneeling. And no wonder. God was speaking to him through Saint Crispinian.

And Nicholas Hook, outlaw and archer, did not know what to do when God spoke to him. He was filled with terror.

The man in the room below threw down his helmet. He unbuckled his sword belt and tossed it aside, then he growled something at the girl before starting to haul his mail coat and its covering surcoat over his head. Hook, peering between the crude floorboards, recognised the badge on the surcoat as Sir Roger Pallaire’s three hawks on a green field. What was that badge doing here? It was the victorious besiegers, not the defeated garrison, who were raping and ransacking the city, yet the three hawks were unmistakably Sir Roger’s arms.

‘Now,’ Saint Crispinian said.

Hook did not move.

‘Now!’ Saint Crispin snarled in Hook’s head. Saint Crispin was not as friendly as Crispinian and Hook flinched when the saint snapped the word.

The man, Hook was not sure whether it was Sir Roger himself or one of his men-at-arms, was struggling with the heavy leather-lined mail coat that was half over his head and constricting his arms.

‘For God’s sake!’ Crispinian appealed to Hook.

‘Do it, boy,’ Saint Crispin said harshly.

‘Save your soul, Nicholas,’ Crispinian said gently.