По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

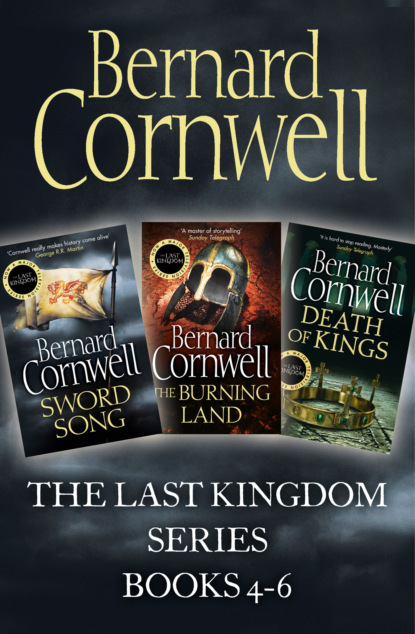

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Very likely to die,’ I said slowly and savagely. Father Cuthbert turned back to speak, caught my eye and his voice faltered. ‘Finan!’ I shouted, and waited till the Irishman came into the house with a naked sword in his hand. ‘How long,’ I asked, ‘do you think young Osferth will live?’

‘He’ll be lucky to survive one day,’ Finan said, assuming I had meant how long Osferth would last in battle.

‘You see?’ I said to Father Cuthbert. ‘He’s sick. He’s going to die. So tell the king I shall grieve for him. And tell the king that the longer my cousin waits, the stronger the enemy becomes in Lundene.’

‘It’s the weather, lord,’ Father Cuthbert said. ‘Lord Æthelred cannot find adequate supplies.’

‘Tell him there’s food in Lundene,’ I said and knew I was wasting my breath.

Æthelred finally came in mid April, and our joint forces now numbered almost eight hundred men, of whom fewer than four hundred were useful. The rest had been raised from the fyrd of Berrocscire or summoned from the lands in southern Mercia that Æthelred had inherited from his father, my mother’s brother. The men of the fyrd were farmers, and they brought axes or hunting bows. A few had swords or spears, and fewer still had any armour other than a leather jerkin, while some marched with nothing but sharpened hoes. A hoe can be a fearful weapon in a street brawl, but it is hardly suitable to beat down a mailed Viking armed with shield, axe, short-sword and long blade.

The useful men were my household troops, a similar number from Æthelred’s household, and three hundred of Alfred’s own guards who were led by the grim-faced, looming Steapa. Those trained men would do the real fighting, while the rest were just there to make our force look large and menacing.

Yet in truth Sigefrid and Erik would know exactly how menacing we were. Throughout the winter and early spring there had been travellers coming upriver from Lundene and some were doubtless the brothers’ spies. They would know how many men we were bringing, how many of those men were true warriors, and those same spies must have reported back to Sigefrid on the day we had last crossed the river to the northern bank.

We made the crossing upstream of Coccham, and it took all day. Æthelred grumbled about the delay, but the ford we used, which had been impassable all winter, was running high again and the horses had to be coaxed over, and the supplies had to be loaded on the ships for the crossing, though not on board Æthelred’s ship, which he insisted could not carry cargo.

Alfred had given his son-in-law the Heofonhlaf to use for the campaign. It was the smaller of Alfred’s river ships, and Æthelred had raised a canopy over the stern to make a sheltered spot just forward of the steersman’s platform. There were cushions there, and pelts, and a table and stools, and Æthelred spent all day watching the crossing from beneath the canopy while servants brought him food and ale.

He watched with Æthelflaed who, to my surprise, accompanied her husband. I first saw her as she walked the small raised deck of the Heofonhlaf and, seeing me, she had raised a hand in greeting. At midday Gisela and I were summoned to her husband’s presence and Æthelred greeted Gisela like an old friend, fussing over her and demanding that a fur cloak be fetched for her. Æthelflaed watched the fuss, then gave me a blank look. ‘You are going back to Wintanceaster, my lady?’ I asked her. She was a woman now, married to an ealdorman, and so I called her my lady.

‘I am coming with you,’ she said blandly.

That startled me. ‘You’re coming …’ I began, but did not finish.

‘My husband wishes it,’ she said very formally, then a flash of the old Æthelflaed showed as she gave me a quick smile, ‘and I’m glad. I want to see a battle.’

‘A battle is no place for a lady,’ I said firmly.

‘Don’t worry the woman, Uhtred!’ Æthelred called across the deck. He had heard my last words. ‘My wife will be quite safe, I have assured her of that.’

‘War is no place for women,’ I insisted.

‘She wishes to see our victory,’Æthelred insisted, ‘and so she shall, won’t you, my duck?’

‘Quack, quack,’ Æthelflaed said so softly that only I could hear. There was bitterness in her tone, but when I glanced at her she was smiling sweetly at her husband.

‘I would come if I could,’ Gisela said, then touched her belly. The baby did not show yet.

‘You can’t,’ I said, and was rewarded by a mocking grimace, then we heard a bellow of rage from the bows of Heofonhlaf.

‘Can’t a man sleep!’ the voice shouted. ‘You Saxon earsling! You woke me up!’

Father Pyrlig had been sleeping under the small platform at the ship’s bows, where some poor man had inadvertently disturbed him. The Welshman now crawled into the sullen daylight and blinked at me. ‘Good God,’ he said with disgust in his voice, ‘it’s the Lord Uhtred.’

‘I thought you were in East Anglia,’ I called to him.

‘I was, but King Æthelstan sent me to make sure you useless Saxons don’t piss down your legs when you see Northmen on Lundene’s walls.’ It took me a moment to remember that Æthelstan was Guthrum’s Christian name. Pyrlig came towards us, a dirty shirt covering his belly where his wooden cross hung. ‘Good morning, my lady,’ he called cheerfully to Æthelflaed.

‘It is afternoon, father,’ Æthelflaed said, and I could tell from the warmth in her voice that she liked the Welsh priest.

‘Is it afternoon? Good God, I slept like a baby. Lady Gisela! A pleasure. My goodness, but all the beauties are gathered here!’ He beamed at the two women. ‘If it wasn’t raining I would think I’d been transported to heaven. My lord,’ the last two words were addressed to my cousin and it was plain from their tone that the two men were not friends. ‘You need advice, my lord?’ Pyrlig asked.

‘I do not,’ my cousin said harshly.

Father Pyrlig grinned at me. ‘Alfred asked me to come as an adviser.’ He paused to scratch a fleabite on his belly. ‘I’m to advise Lord Æthelred.’

‘As am I,’ I said.

‘And doubtless Lord Uhtred’s advice would be the same as mine,’ Pyrlig went on, ‘which is that we must move with the speed of a Saxon seeing a Welshman’s sword.’

‘He means we must move fast,’ I explained to Æthelred, who knew perfectly well what the Welshman had meant.

My cousin ignored me. ‘Are you being deliberately offensive?’ he asked Pyrlig stiffly.

‘Yes, lord!’ Pyrlig grinned, ‘I am!’

‘I have killed dozens of Welshmen,’ my cousin said.

‘Then the Danes will be no problem to you, will they?’ Pyrlig retorted, refusing to take offence. ‘But my advice still stands, lord. Make haste! The pagans know we’re coming, and the more time you give them, the more formidable their defences!’

We might have moved fast had we possessed ships to carry us downriver, but Sigefrid and Erik, knowing we were coming, had blocked all traffic on the Temes and, not counting Heofonhlaf, we could only muster seven ships, not nearly sufficient to carry our men and so only the laggards and the supplies and Æthelred’s cronies travelled by water. So we marched and it took us four days, and every day we saw horsemen to the north of us or ships downstream of us, and I knew those were Sigefrid’s scouts, making a last count of our numbers as our clumsy army lumbered ever nearer Lundene. We wasted one whole day because it was a Sunday and Æthelred insisted that the priests accompanying the army said mass. I listened to the drone of voices and watched the enemy horsemen circle around us. Haesten, I knew, would already have reached Lundene, and his men, at least two or three hundred of them, would be reinforcing the walls.

Æthelred travelled on board the Heofonhlaf, only coming ashore in the evening to walk around the sentries I had posted. He made a point of moving those sentries, as if to suggest I did not know my business, and I let him do it. On the last night of the journey we camped on an island that was reached from the north bank by a narrow causeway, and its reed-fringed shore was thick with mud so that Sigefrid, if he had a mind to attack us, would find our camp hard to approach. We tucked our ships into the creek that twisted to the island’s north and, as the tide went down and the frogs filled the dusk with croaking, the hulls settled into the thick mud. We lit fires on the mainland that would illuminate the approach of any enemy, and I posted men all around the island.

Æthelred did not come ashore that evening. Instead he sent a servant who demanded that I go to him on board the Heofonhlaf and so I took off my boots and trousers and waded through the glutinous muck before hauling myself over the ship’s side. Steapa, who was marching with the men from Alfred’s bodyguard, came with me. A servant drew buckets of river water from the ship’s far side and we cleaned the mud from our legs, then dressed again before joining Æthelred under his canopy at the Heofonhlaf’s stern. My cousin was accompanied by the commander of his household guard, a young Mercian nobleman named Aldhelm who had a long, supercilious face, dark eyes and thick black hair that he oiled to a lustrous sheen.

Æthelflaed was also there, attended by a maid and by a grinning Father Pyrlig. I bowed to her and she smiled back, but without enthusiasm, and then bent to her embroidery, which was illuminated by a horn-shielded lantern. She was threading white wool onto a dark grey field, making the image of a prancing horse that was her husband’s banner. The same banner, much larger, hung motionless at the ship’s mast. There was no wind, so the smoke from the fires of Lundene’s two towns was a motionless smear in the darkening east.

‘We attack at dawn,’ Æthelred announced without so much as a greeting. He was dressed in a mail coat and had his swords, short and long, belted at his waist. He was looking unusually smug, though he tried to make his voice casual. ‘But I will not sound the advance for my troops,’ he went on, ‘until I hear your own attack has started.’

I frowned at those words. ‘You won’t start your attack,’ I repeated cautiously, ‘until you hear mine has started?’

‘That’s plain, isn’t it?’ Æthelred demanded belligerently.

‘Very plain,’ Aldhelm said mockingly. He treated Æthelred in the same manner that Æthelred behaved to Alfred and, secure in my cousin’s favour, felt free to offer me veiled insult.

‘It’s not plain to me!’ Father Pyrlig put in energetically. ‘The agreed plan,’ the Welshman went on, speaking to Æthelred, ‘is for you to make a feint attack on the western walls and, when you have drawn defenders from the north wall, for Uhtred’s men to make the real assault.’

‘Well I’ve changed my mind,’ Æthelred said airily. ‘Uhtred’s men will now provide the diversionary attack, and my assault will be the real one.’ He tilted up his broad chin and stared at me, daring me to contradict him.

Æthelflaed also looked at me, and I sensed she wanted me to oppose her husband, but instead I surprised all of them by bowing my head as if in acquiescence. ‘If you insist,’ I said.

‘I do,’ Æthelred said, unable to conceal his pleasure at gaining the apparent victory so easily. ‘You may take your own household troops,’ he went on grudgingly, as though he possessed the authority to take them away from me, ‘and thirty other men.’

‘We agreed I could have fifty,’ I said.

‘I have changed my mind about that too!’ he said pugnaciously. He had already insisted that the men of the Berrocscire fyrd, my men, would swell his ranks, and I had meekly agreed to that, just as I had now agreed that the glory of the successful assault could be his. ‘You may take thirty,’ he went on harshly. I could have argued and maybe I should have argued, but I knew it would do no good. Æthelred was beyond argument, wanting only to demonstrate his authority in front of his young wife. ‘Remember,’ he said, ‘that Alfred gave me command here.’