По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

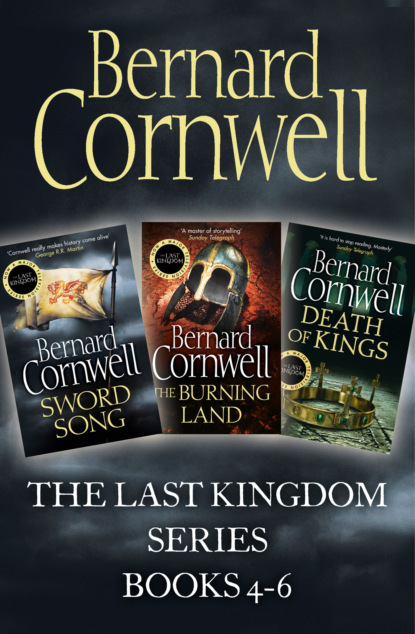

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You were?’ he asked, squinting up at me. ‘Well, you shouldn’t have been talking. It’s just plain bad manners! And insulting to God! I’m astonished at you, Uhtred, I really am! I’m astonished and disappointed.’

‘Yes, father,’ I said, smiling. Beocca had been reproving me for years. When I was a child, Beocca was my father’s priest and confessor and, like me, he had fled Northumbria when my uncle had usurped Bebbanburg. Beocca had found a refuge at Alfred’s court where his piety, his learning and his enthusiasm were appreciated by the king. That royal favour went a long way to stop men mocking Beocca, who was, in all truth, as ugly a man as you could have found in all Wessex. He had a club foot, a squint, and a palsied left hand. He was blind in his wandering eye that had gone as white as his hair, for he was now nearly fifty years old. Children jeered at him in the streets and some folk made the sign of the cross, believing that ugliness was a mark of the devil, but he was as good a Christian as any I have ever known. ‘It is good to see you,’ he said in a dismissive tone, as if he feared I might believe him. ‘You do know the king wishes to speak with you? I suggested you meet him after the feast.’

‘I’ll be drunk.’

He sighed, then reached out with his good hand to hide the amulet of Thor’s hammer that was showing at my neck. He tucked it under my tunic. ‘Try to stay sober,’ he said.

‘Tomorrow, perhaps?’

‘The king is busy, Uhtred! He doesn’t wait on your convenience!’

‘Then he’ll have to talk to me drunk,’ I said.

‘And I warn you he wants to know how soon you can take Lundene. That’s why he wishes to speak with you.’ He stopped talking abruptly because Gisela and Thyra were walking towards us, and Beocca’s face was suddenly transformed by happiness. He just stared at Thyra like a man seeing a vision and, when she smiled at him, I thought his heart would burst with pride and devotion. ‘You’re not cold, are you, my dear?’ he asked solicitously. ‘I can fetch you a cloak.’

‘I’m not cold.’

‘Your blue cloak?’

‘I am warm, my dear,’ she said, and put a hand on his arm.

‘It will be no trouble!’ Beocca said.

‘I am not cold, dearest,’ Thyra said, and again Beocca looked as though he would die of happiness.

All his life Beocca had dreamed of women. Of fair women. Of a woman who would marry him and give him children, and for all his life his grotesque appearance had made him an object of scorn until, on a hilltop of blood, he had met Thyra and he had banished the demons from her soul. They had been married four years now. To look at them was to be certain that no two people were ever more ill-suited to each other. An old, ugly, meticulous priest and a young, golden-haired Dane, but to be near them was to feel their joy like the warmth of a great fire on a winter’s night. ‘You shouldn’t be standing, my dear,’ he told her, ‘not in your condition. I shall fetch you a stool.’

‘I shall be sitting soon, dearest.’

‘A stool, I think, or a chair. And are you sure you don’t need a cloak? It would really be no trouble to fetch one!’

Gisela looked at me and smiled, but Beocca and Thyra were oblivious of us as they fussed over each other. Then Gisela gave the smallest jerk of her head and I looked to see that a young monk was standing nearby and staring at me. He had obviously been waiting to catch my eye, and he was just as obviously nervous. He was thin, not very tall, brown haired and had a pale face that looked remarkably like Alfred’s. There was the same drawn and anxious look, the same serious eyes and thin mouth, and evidently the same piety judging by the monk’s robe. He was a novice, because his hair was untonsured, and he dropped to one knee when I looked at him. ‘Lord Uhtred,’ he said humbly.

‘Osferth!’ Beocca said, becoming aware of the young monk’s presence. ‘You should be at your studies! The wedding is over and novices are not invited to the feast.’

Osferth ignored Beocca. Instead, with his head bowed, he spoke to me. ‘You knew my uncle, lord.’

‘I did?’ I asked suspiciously. ‘I have known many men,’ I said, preparing him for the refusal I was sure I would offer to whatever he requested of me.

‘Leofric, lord.’

And my suspicion and hostility vanished at the mention of that name. Leofric. I even smiled. ‘I knew him,’ I said warmly, ‘and I loved him.’ Leofric had been a tough West Saxon warrior who had taught me about war. Earsling, he used to call me, meaning something dropped from an arse, and he toughened me, bullied me, snarled at me, beat me and became my friend and remained my friend until the day he died on the rain-swept battlefield at Ethandun.

‘My mother is his sister, lord,’ Osferth said.

‘To your studies, young man!’ Beocca said sternly.

I put a hand on Beocca’s palsied arm to hold him back. ‘Your mother’s name?’ I asked Osferth.

‘Eadgyth, lord.’

I leaned down and tipped Osferth’s face up. No wonder he looked like Alfred, for this was Alfred’s bastard son who had been whelped on a palace servant-girl. No one ever admitted that Alfred was the boy’s father, though it was an open secret. Before Alfred found God he had discovered the joys of palace maids, and Osferth was the product of that youthful exuberance. ‘Does Eadgyth live?’ I asked him.

‘No, lord. She died of the fever two years ago.’

‘And what are you doing here, in Wintanceaster?’

‘He is studying for the church,’ Beocca snapped, ‘because his calling is to be a monk.’

‘I would serve you, lord,’ Osferth said anxiously, staring up into my face.

‘Go!’ Beocca tried to shoo the young man away. ‘Go! Go away! Back to your studies, or I shall have the novice-master whip you!’

‘Have you ever held a sword?’ I asked Osferth.

‘The one my uncle gave me, lord, I have it.’

‘But you’ve not fought with it?’

‘No, lord,’ he said, and still he looked up at me, so anxious and frightened, and with a face so like his father’s face.

‘We are studying the life of Saint Cedd,’ Beocca said to Osferth, ‘and I expect you to have copied the first ten pages by sundown.’

‘Do you want to be a monk?’ I asked Osferth.

‘No, lord,’ he said.

‘Then what?’ I asked, ignoring Father Beocca who was spluttering protests, but unable to advance past my sword arm that held him back.

‘I would follow my uncle’s steps, lord,’ Osferth said.

I almost laughed. Leofric had been as hard a warrior as ever lived and died, while Osferth was a puny, pale youth, but I managed to keep a straight face. ‘Finan!’ I shouted.

The Irishman appeared at my side. ‘Lord?’

‘This young man is joining my household troops,’ I said, handing Finan some coins.

‘You can’t …’ Beocca began protesting, then went silent when both Finan and I stared at him.

‘Take Osferth away,’ I told Finan, ‘find him clothes fit for a man, and get him weapons.’

Finan looked dubiously at Osferth. ‘Weapons?’ he asked.

‘He has the blood of warriors,’ I said, ‘so now we will teach him to fight.’

‘Yes, lord,’ Finan said, his tone suggesting he thought I was mad, but then he looked at the coins I had given him and saw a chance of profit. He grinned. ‘We’ll make him a warrior yet, lord,’ he said, doubtless believing he lied, then he led Osferth away.

Beocca rounded on me. ‘Do you know what you’ve just done?’ he spluttered.