По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

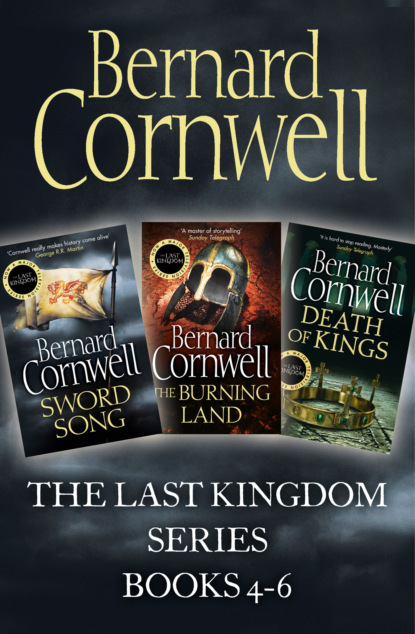

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Fate decrees what we do. We cannot escape fate. Wyrd bið ful ãræd. We have no choices in life, how can we? Because from the moment we are born the three sisters know where our thread will go and what patterns it will weave and how it will end. Wyrd bið ful ãræd.

Yet we choose our oaths. Alfred, when he gave me his sword and hands to enfold in my hands did not order me to make the oath. He offered it and I chose. But was it my choice? Or did the Fates choose for me? And if they did, why bother with oaths? I have often wondered about this and even now, as an old man, I still wonder. Did I choose Alfred? Or were the Fates laughing when I knelt and took his sword and hands in mine?

The three Norns were certainly laughing on that cold bright day in Lundene, because the moment I saw that the big-bellied priest was Father Pyrlig I knew that nothing was simple. I had realised in that instant that the Fates had not spun me a golden thread leading to a throne. They were laughing from the roots of Yggdrasil, the tree of life. They had made a jest and I was its victim, and I had to make a choice.

Or did I? Maybe the Fates had made the choice, but at that moment, overshadowed by the gaunt stark makeshift cross, I believed I had to choose between the Thurgilson brothers and Pyrlig.

Sigefrid was no friend, but he was a formidable man, and with his alliance I could become king in Mercia. Gisela would be a queen. I could help Sigefrid, Erik, Haesten and Ragnar plunder Wessex. I could become rich. I would lead armies. I would fly my banner of the wolf’s head, and at Smoca’s heels would ride a mailed host of spearmen. My enemies would hear the thunder of our hooves in their nightmares. All that would be mine if I chose to ally myself with Sigefrid.

While by choosing Pyrlig I would lose all that the dead man had promised me. Which meant that Bjorn had lied, yet how could a man sent from his grave with a message from the Norns tell a lie? I remember thinking all that in the heartbeat before I made my choice, though in truth there was no hesitation. There was not even a heartbeat of hesitation.

Pyrlig was a Welshman, a Briton, and we Saxons hate the Britons. The Britons are treacherous thieves. They hide in their hill fastnesses and ride down to raid our lands, and they take our cattle and sometimes our women and children, and when we pursue them they go ever deeper into a wild place of mists, crags, marsh and misery. And Pyrlig was also a Christian, and I have no love for Christians. The choice would seem so easy! On one side a kingdom, Viking friends and wealth, and on the other a Briton who was the priest of a religion that sucks joy from this world like dusk swallowing daylight. Yet I did not think. I chose, or fate chose, and I chose friendship. Pyrlig was my friend. I had met him in Wessex’s darkest winter, when the Danes seemed to have conquered the kingdom, and Alfred with a few followers had been driven to take refuge in the western marshes. Pyrlig had been sent as an emissary by his Welsh king to discover and perhaps exploit Alfred’s weakness, but instead he had sided with Alfred and fought for Alfred. Pyrlig and I had stood in the shield wall together. We had fought side by side. We were Welshman and Saxon, Christian and pagan, and we should have been enemies, but I loved him like a brother.

So I gave him my sword and, instead of watching him nailed to a cross, I gave him the chance to fight for his life.

And, of course, it was not a fair fight. It was over in a moment! Indeed, it had hardly begun before it ended, and I alone was not astonished by its ending.

Sigefrid was expecting to face a fat, untrained priest, yet I knew that Pyrlig had been a warrior before he discovered his god. He had been a great warrior, a killer of Saxons and a man about whom his people had made songs. He did not look like a great warrior now. He was half naked, fat, dishevelled, bruised and beaten. He waited for Sigefrid’s attack with a look of horrified terror on his face and with the tip of Serpent-Breath’s blade still resting on the ground. He backed away as Sigefrid came closer, and began making mewing noises. Sigefrid laughed and swung his sword almost idly, expecting to knock Pyrlig’s blade out of his path and so expose that big belly to Fear-Giver’s gut-opening slash.

And Pyrlig moved like a weasel.

He lifted Serpent-Breath gracefully and danced a backwards pace so that Sigefrid’s careless swing went under her blade, and then he stepped towards his enemy and brought Serpent-Breath down hard, all wrist in that stroke, and sliced her against Sigefrid’s sword arm as it was still swinging outwards. The stroke was not powerful enough to break the mail armour, but it did drive Sigefrid’s sword arm further out and so opened the Norseman to a lunge. And Pyrlig lunged. He was so fast that Serpent-Breath was a silver blur that struck hard on Sigefrid’s chest.

Once again the blade did not pierce Sigefrid’s mail. Instead it pushed the big man backwards and I saw the fury come into the Norseman’s eyes and saw him bring Fear-Giver back in a mighty swing that would surely have decapitated Pyrlig in a red instant. There was so much strength and savagery in that huge cut, but Pyrlig, who seemed a heartbeat from death, simply used his wrist again. He did not seem to move, but still Serpent-Breath flickered up and sideways.

Serpent-Breath’s point met that death-swing on the inside of Sigefrid’s wrist and I saw the spray of blood like a red fog in the air.

And I saw Pyrlig smile. It was more of a grimace, but there was a warrior’s pride and a warrior’s triumph in that smile. His blade had ripped up Sigefrid’s forearm, slicing the mail apart and laying open flesh and skin and muscle from wrist to elbow, so that Sigefrid’s mighty blow faltered and stopped. The Norseman’s sword arm went limp, and Pyrlig suddenly stepped back and turned Serpent-Breath so he could cut downwards with her and at last he appeared to put some effort into the blade. She made a whistling noise as the Welshman slashed her onto Sigefrid’s bleeding wrist. He almost severed the wrist, but the blade glanced off a bone and took the Norseman’s thumb instead, and Fear-Giver fell to the arena floor and Serpent-Breath was in Sigefrid’s beard and at his throat.

‘No!’ I shouted.

Sigefrid was too appalled to be angry. He could not believe what had happened. He must have realised by that moment that his opponent was a swordsman, but still he could not believe he had lost. He brought up his bleeding hands as if to seize Pyrlig’s blade, and I saw the Welshman’s blade twitch and Sigefrid, sensing death a hair’s breadth away, went still.

‘No,’ I repeated.

‘Why shouldn’t I kill him?’ Pyrlig asked, and his voice was a warrior’s voice now, hard and merciless, and his eyes were warrior’s eyes, flint-cold and furious.

‘No,’ I said again. I knew that if Pyrlig killed Sigefrid then Sigefrid’s men would have their revenge.

Erik knew it too. ‘You won, priest,’ he said softly. He walked to his brother. ‘You won,’ he said again to Pyrlig, ‘so put down the sword.’

‘Does he know I beat him?’ Pyrlig asked, staring into Sigefrid’s dark eyes.

‘I speak for him,’ Erik said. ‘You won the fight, priest, and you are free.’

‘I have to deliver my message first,’ Pyrlig said. Blood dripped from Sigefrid’s hand. He still stared at the Welshman. ‘The message we bring from King Æthelstan,’ Pyrlig said, meaning Guthrum, ‘is that you are to leave Lundene. It is not part of the land ceded by Alfred to Danish rule. Do you understand that?’ He twitched Serpent-Breath again, though Sigefrid said nothing. ‘Now I want horses,’ Pyrlig went on, ‘and Lord Uhtred and his men are to escort us out of Lundene. Is that agreed?’

Erik looked at me and I nodded consent. ‘It is agreed,’ Erik said to Pyrlig.

I took Serpent-Breath from Pyrlig’s hand. Erik was holding his brother’s wounded arm. For a moment I thought Sigefrid would attack the unarmed Welshman, but Erik managed to turn him away.

Horses were fetched. The men in the arena were silent and resentful. They had seen their leader humiliated, and they did not understand why Pyrlig was allowed to leave with the other envoys, but they accepted Erik’s decision.

‘My brother is headstrong,’ Erik told me. He had taken me aside to talk while the horses were saddled.

‘It seems the priest knew how to fight after all,’ I said apologetically.

Erik frowned, not with anger, but puzzlement. ‘I am curious about their god,’ he admitted. He was watching his brother, whose wounds were being bandaged. ‘Their god does seem to have power,’ Erik said. I slid Serpent-Breath into her scabbard and Erik saw the silver cross that decorated her pommel. ‘You must think so too?’

‘That was a gift,’ I said, ‘from a woman. A good woman. A lover. Then the Christian god took hold of her and she loves men no more.’

Erik reached out and touched the cross tentatively. ‘You don’t think it gives the blade power?’ he asked.

‘The memory of her love might,’ I said, ‘but power comes from here.’ I touched my amulet, Thor’s hammer.

‘I fear their god,’ Erik said.

‘He’s harsh,’ I said, ‘unkind. He’s a god who likes to make laws.’

‘Laws?’

‘You’re not allowed to lust after your neighbour’s wife,’ I said.

Erik laughed at that, then saw I was serious. ‘Truly?’ he asked with disbelief in his voice.

‘Priest!’ I called to Pyrlig. ‘Does your god let men lust after their neighbours’ wives?’

‘He lets them, lord,’ Pyrlig said humbly as if he feared me, ‘but he disapproves.’

‘Did he make a law about it?’

‘Yes, lord, he did. And he made another that says you mustn’t lust after your neighbour’s ox.’

‘There,’ I said to Erik. ‘You can’t even wish for an ox if you’re a Christian.’

‘Strange,’ he said thoughtfully. He was looking at Guthrum’s envoys who had so narrowly escaped losing their heads. ‘You don’t mind escorting them?’

‘No.’

‘It might be no bad thing if they live,’ he said quietly. ‘Why give Guthrum cause to attack us?’

‘He won’t,’ I said confidently, ‘whether you kill them or not.’

‘Probably not,’ he agreed, ‘but we agreed that if the priest won, then they would all live, so let them live. And you’re sure you don’t mind escorting them away?’

‘Of course not,’ I said.

‘Then come back here,’ Erik said warmly, ‘we need you.’