По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

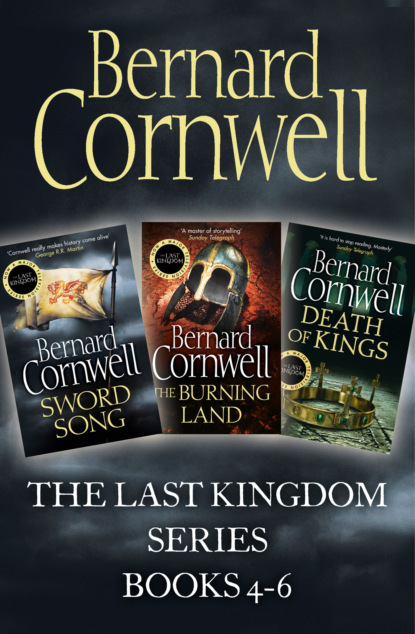

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then, in the silence, Haesten suddenly knelt to me. ‘Lord King,’ he said, and there was unexpected reverence in his voice.

‘You broke an oath to me,’ I said harshly. Why did I say that then? I could have confronted him earlier, in the hall, but it was by that opened grave I made the accusation.

‘I did, lord King,’ he said, ‘and I regret it.’

I paused. What was I thinking? That I was a king already? ‘I forgive you,’ I said. I could hear my heartbeat. Bjorn just watched and the light of the flaming torches cast deep shadows on his face.

‘I thank you, lord King,’ Haesten said, and beside him Eilaf the Red knelt and then every man in that damp graveyard knelt to me.

‘I am not king yet,’ I said, suddenly ashamed of the lordly tones I had used to Haesten.

‘You will be, lord,’ Haesten said. ‘The Norns say so.’

I turned to the corpse. ‘What else did the three spinners say?’

‘That you will be king,’ Bjorn said, ‘and you will be the king of other kings. You will be lord of the land between the rivers and the scourge of your enemies. You will be king.’ He stopped suddenly and went into spasm, his upper body jerking forward and then the spasms stopped and he stayed motionless, bent forward, retching drily, before slowly crumpling onto the disturbed earth.

‘Bury him again,’ Haesten said harshly, rising from his knees and speaking to the men who had cut the Saxon’s throat.

‘His harp,’ I said.

‘I will return it to him tomorrow, lord,’ Haesten said, then gestured towards Eilaf’s hall. ‘There is food, lord King, and ale. And a woman for you. Two if you want.’

‘I have a wife,’ I said harshly.

‘Then there is food, ale and warmth for you,’ he said humbly. The other men stood. My warriors looked at me strangely, confused by the message they had heard, but I ignored them. King of other kings. Lord of the land between the rivers. King Uhtred.

I looked back once and saw the two men scraping at the soil to make Bjorn’s grave again, and then I followed Haesten into the hall and took the chair at the table’s centre, the lord’s chair, and I watched the men who had witnessed the dead rise, and I saw they were convinced as I was convinced, and that meant they would take their troops to Haesten’s side. The rebellion against Guthrum, the rebellion that was meant to spread across Britain and destroy Wessex, was being led by a dead man. I rested my head on my hands and I thought. I thought of being king. I thought of leading armies.

‘Your wife is Danish, I hear?’ Haesten interrupted my thoughts.

‘She is,’ I said.

‘Then the Saxons of Mercia will have a Saxon king,’ he said, ‘and the Danes of Mercia will have a Danish queen. They will both be happy.’

I raised my head and stared at him. I knew him to be clever and sly, but that night he was carefully subservient and genuinely respectful. ‘What do you want, Haesten?’ I asked him.

‘Sigefrid and his brother,’ he said, ignoring my question, ‘want to conquer Wessex.’

‘The old dream,’ I said scornfully.

‘And to do it,’ he said, disregarding my scorn, ‘we shall need men from Northumbria. Ragnar will come if you ask him.’

‘He will,’ I agreed.

‘And if Ragnar comes, others will follow.’ He broke a loaf of bread and pushed the greater part towards me. A bowl of stew was in front of me, but I did not touch it. Instead I began to crumble the bread, feeling for the granite chips that are left from the grindstone. I was not thinking about what I did, just keeping my hands busy while I watched Haesten.

‘You didn’t answer my question,’ I said. ‘What do you want?’

‘East Anglia,’ he said.

‘King Haesten?’

‘Why not?’ he said, smiling.

‘Why not, lord King,’ I retorted, provoking a wider smile.

‘King Æthelwold in Wessex,’ Haesten said, ‘King Haesten in East Anglia, and King Uhtred in Mercia.’

‘Æthelwold?’ I asked scornfully, thinking of Alfred’s drunken nephew.

‘He is the rightful King of Wessex, lord,’ Haesten said.

‘And how long will he live?’ I asked.

‘Not long,’ Haesten admitted, ‘unless he is stronger than Sigefrid.’

‘So it will be Sigefrid of Wessex?’ I asked.

Haesten smiled. ‘Eventually, lord, yes.’

‘What of his brother, Erik?’

‘Erik likes to be a Viking,’ Haesten said. ‘His brother takes Wessex and Erik takes the ships. Erik will be a sea king.’

So it would be Sigefrid of Wessex, Uhtred of Mercia and Haesten in East Anglia. Three weasels in a sack, I thought, but did not let the thought show. ‘And where,’ I asked instead, ‘does this dream begin?’

His smile went. He was serious now. ‘Sigefrid and I have men. Not enough, but the heart of a good army. You bring Ragnar south with the Northumbrian Danes and we’ll have more than enough to take East Anglia. Half of Guthrum’s earls will join us when they see you and Ragnar. Then we take the men of East Anglia, join them to our army, and conquer Mercia.’

‘And join the men of Mercia,’ I finished for him, ‘to take Wessex?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘When the leaves fall,’ he went on, ‘and when the barns are filled, we shall march on Wessex.’

‘But without Ragnar,’ I said, ‘you can do nothing.’

He bowed his head in agreement. ‘And Ragnar will not march unless you join us.’

It could work, I thought. Guthrum, the Danish King of East Anglia, had repeatedly failed to conquer Wessex and now had made his peace with Alfred, but just because Guthrum had become a Christian and was now an ally of Alfred did not mean that other Danes had abandoned the dream of Wessex’s rich fields. If enough men could be assembled, then East Anglia would fall, and its earls, ever eager for plunder, would march on Mercia. Then Northumbrians, Mercians and East Anglians could turn on Wessex, the richest kingdom and the last Saxon kingdom in the land of the Saxons.

Yet I was sworn to Alfred. I was sworn to defend Wessex. I had given Alfred my oath and without oaths we are no better than beasts. But the Norns had spoken. Fate is inexorable, it cannot be cheated. That thread of my life was already in place, and I could no more change it than I could make the sun go backwards. The Norns had sent a messenger across the black gulf to tell me that my oath must be broken, and that I would be a king, and so I nodded to Haesten. ‘So be it,’ I said.

‘You must meet Sigefrid and Erik,’ he said, ‘and we must make oaths.’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Tomorrow,’ he said, watching me carefully, ‘we leave for Lundene.’

So it had begun. Sigefrid and Erik were readying to defend Lundene, and by doing that they defied the Mercians, who claimed the city as theirs, and they defied Alfred, who feared Lundene being garrisoned by an enemy, and they defied Guthrum, who wanted the peace of Britain kept. But there would be no peace.