По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

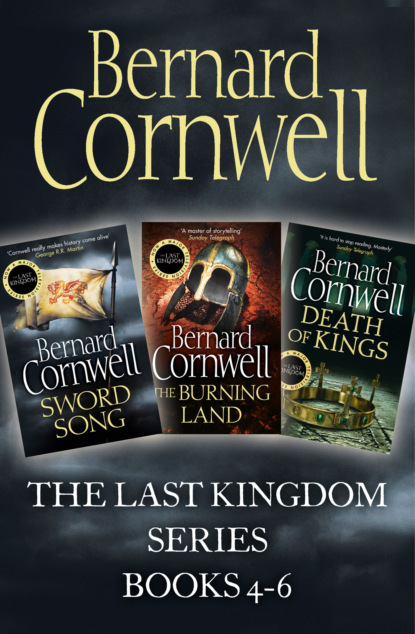

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He fell silent again, and I knew what he was thinking. He was thinking that the Temes is our road to other kingdoms, to the rest of the world, and if the Danes and the Norse block the Temes, then Wessex was cut off from much of the world’s trade. Of course there were other ports and other rivers, but the Temes is the great river that sucks in vessels from all the wide seas. ‘Do they want money?’ he asked bitterly.

‘That is Mercia’s problem, lord,’ I suggested.

‘Don’t be a fool!’ he snapped at me. ‘Lundene might be in Mercia, but the river belongs to both of us.’ He turned around again, staring downriver almost as though he expected to see the masts of Norse ships appearing in the distance. ‘If they will not go,’ he said quietly, ‘then they will have to be expelled.’

‘Yes, lord.’

‘And that,’ he said decisively, ‘will be my wedding gift to your cousin.’

‘Lundene?’

‘And you will provide it,’ he said savagely. ‘You will restore Lundene to Mercian rule, Lord Uhtred. Let me know by the Feast of Saint David what force you will need to secure the gift.’ He frowned, thinking. ‘Your cousin will command the army, but he is too busy to plan the campaign. You will make the necessary preparations and advise him.’

‘I will?’ I asked sourly.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘you will.’

He did not stay to eat. He said prayers in the church, gave silver to the nunnery, then embarked on Haligast and vanished upstream.

And I was to capture Lundene and give all the glory to my cousin Æthelred.

The summons to meet the dead came two weeks later and took me by surprise.

Each morning, unless the snow was too thick for easy travel, a crowd of petitioners waited at my gate. I was the ruler in Coccham, the man who dispensed justice, and Alfred had granted me that power, knowing it was essential if his burh was to be built. He had given me more. I was entitled to a tenth part of every harvest in northern Berrocscire, I was given pigs and cattle and grain, and from that income I paid for the timber that made the walls and the weapons that guarded them. There was opportunity in that, and Alfred suspected me, which is why he had given me a sly priest called Wulfstan, whose task was to make sure I did not steal too much. Yet it was Wulfstan who stole. He had come to me in the summer, half grinning, and pointed out that the dues we collected from the merchants who used the river were unpredictable, which meant Alfred could never estimate whether we were keeping proper accounts. He waited for my approval and got a thump about his tonsured skull instead. I sent him to Alfred under guard with a letter describing his dishonesty, and then I stole the dues myself. The priest had been a fool. You never, ever, tell others of your crimes, not unless they are so big as to be incapable of concealment, and then you describe them as policy or statecraft.

I did not steal much, no more than another man in my position would put aside, and the work on the burh’s walls proved to Alfred that I was doing my job. I have always loved building and life has few ordinary pleasures greater than chatting with the skilled men who split, shape and join timbers. I dispensed justice too, and I did that well, because my father, who had been Lord of Bebbanburg in Northumbria, had taught me that a lord’s duty was to the folk he ruled, and that they would forgive a lord many sins so long as he protected them. So each day I would listen to misery, and some two weeks after Alfred’s visit I remember a morning of spitting rain in which some two dozen folk knelt to me in the mud outside my hall. I cannot remember all the petitions now, but doubtless they were the usual complaints of boundary stones being moved or of a marriage-price unpaid. I made my decisions swiftly, gauging my judgments by the demeanour of the petitioners. I usually reckoned a defiant petitioner was probably lying, while a tearful one elicited my pity. I doubt I got every decision right, but folk were content enough with my judgments and they knew I did not take bribes to favour the wealthy.

I do remember one petitioner that morning. He was solitary, which was unusual, for most folk arrived with friends or relatives to swear the truth of their complaints, but this man came alone and continually allowed others to get ahead of him. He plainly wanted to be the last to talk to me, and I suspected he wanted a lot of my time and I was tempted to end the morning session without granting him audience, but in the end I let him speak and he was mercifully brief.

‘Bjorn has disturbed my land, lord,’ he said. He was kneeling and all I could see of him was his tangled and dirt-crusted hair.

For a moment I did not recognise the name. ‘Bjorn?’ I demanded. ‘Who is Bjorn?’

‘The man who disturbs my land, lord, in the night.’

‘A Dane?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘He comes from his grave, lord,’ the man said, and I understood then and hushed him to silence so that the priest who noted down my judgments would not learn too much.

I tipped up the petitioner’s head to see a scrawny face. By his tongue I reckoned him for a Saxon, but perhaps he was a Dane who spoke our tongue perfectly, so I tried him in Danish. ‘Where have you come from?’ I asked.

‘From the disturbed ground, lord,’ he answered in Danish, but it was obvious from the way he mangled the words that he was no Dane.

‘Beyond the street?’ I spoke English again.

‘Yes, lord,’ he said.

‘And when does Bjorn disturb your land again?’

‘The day after tomorrow, lord. He will come after moonrise.’

‘You are sent to guide me?’

‘Yes, lord.’

We rode next day. Gisela wanted to come, but I would not allow her for I did not wholly trust the summons, and because of that mistrust I rode with six men; Finan, Clapa, Sihtric, Rypere, Eadric and Cenwulf. The last three were Saxons, Clapa and Sihtric were Danes, and Finan was the fiery Irishman who commanded my household troops, and all six were my oath-men. My life was theirs as theirs was mine. Gisela stayed behind Coccham’s walls, guarded by the fyrd and by the remainder of my household troops.

We rode in mail and we carried weapons. We went west and north first because the Temes was winter swollen and we had to ride a long way upstream to find a ford shallow enough to be crossed. That was at Welengaford, another burh, and I noted how the earth walls were unfinished and how the timber to make the palisades lay rotting and untrimmed in the mud. The commander of the garrison, a man named Oslac, wanted to know why we crossed the river, and it was his right to know because he guarded this part of the frontier between Wessex and lawless Mercia. I said a fugitive had fled Coccham and was thought to be skulking on the Temes’s northern bank, and Oslac believed the tale. It would reach Alfred soon enough.

The man who had brought the summons was our guide. He was called Huda and he told me he served a Dane named Eilaf who had an estate that bordered the eastern side of Wæclingastræt. That made Eilaf an East Anglian and a subject of King Guthrum. ‘Is Eilaf a Christian?’ I asked Huda.

‘We are all Christians, lord,’ Huda said, ‘King Guthrum demands it.’

‘So what does Eilaf wear about his neck?’ I asked.

‘The same as you, lord,’ he said. I wore Thor’s hammer because I was no Christian and Huda’s answer told me that Eilaf, like me, worshipped the older gods, though to please his king, Guthrum, he pretended to a belief in the Christian god. I had known Guthrum in the days when he had led great armies to attack Wessex, but he was getting old now. He had adopted his enemy’s religion and it seemed he no longer wanted to rule all Britain, but was content with the wide fertile fields of East Anglia as his kingdom. Yet there were many in his lands who were not content. Sigefrid, Erik, Haesten, and probably Eilaf. They were Norsemen and Danes, they were warriors, they sacrificed to Thor and to Odin, they kept their swords sharp and they dreamed, as all Northmen dream, of the richer lands of Wessex.

We rode through Mercia, the land without a king, and I noted how many farmsteads had been burned so that the only trace of their existence was now a patch of scorched earth where weeds grew. More weeds smothered what had been ploughland. Hazel saplings had invaded the pastures. Where folk did still live, they lived in fear and when they saw us coming they ran to the woodlands, or else shut themselves behind palisades. ‘Who rules here?’ I asked Huda.

‘Danes,’ he said, then jerked his head westwards, ‘Saxons over there.’

‘Eilaf doesn’t want this land?’

‘He has much of it, lord,’ Huda said, ‘but the Saxons harass him.’

According to the treaty between Alfred and Guthrum this land was Saxon, but the Danes are land hungry and Guthrum could not control all his thegns. So this was battle land, a place where both sides fought a sullen, small and endless war, and the Danes were offering me its crown.

I am a Saxon. A northerner. I am Uhtred of Bebbanburg, but I had been raised by the Danes and I knew their ways. I spoke their tongue, I had married a Dane, and I worshipped their gods. If I were to be king here then the Saxons would know they had a Saxon ruler while the Danes would accept me because I had been as a son to Earl Ragnar. But to be king here was to turn on Alfred and, if the dead man had spoken truly, to put Alfred’s drunken nephew on the throne of Wessex, and how long would Æthelwold last? Less than a year, I reckoned, before the Danes killed him, and then all England would be under Danish rule except for Mercia where I, a Saxon who thought like a Dane, would be king. And how long would the Danes tolerate me?

‘Do you want to be a king?’ Gisela had asked me the night before we rode.

‘I never thought I did,’ I answered cautiously.

‘Then why go?’

I had stared into the fire. ‘Because the dead man brings a message from the Fates,’ I told her.

She had touched her amulet. ‘The Fates can’t be avoided,’ she said softly. Wyrd bið ful ãræd.

‘So I must go,’ I said, ‘because fate demands it. And because I want to see a dead man talk.’

‘And if the dead man says you are to be a king?’

‘Then you will be a queen,’ I said.

‘And you will fight Alfred?’ Gisela asked.

‘If the Fates say so,’ I said.