По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

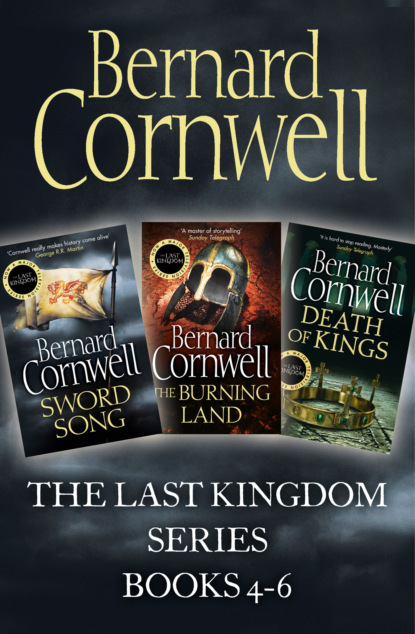

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Tomorrow,’ Haesten said again, ‘we leave for Lundene.’

We rode next day. I led my six men while Haesten had twenty-one companions, and we followed Wæclingastræt south through a persistent rain that turned the road’s verges to thick mud. The horses were miserable, we were miserable. As we rode I tried to remember every word that Bjorn the Dead had said to me, knowing that Gisela would want the conversation recounted in every detail.

‘So?’ Finan challenged me soon after midday. Haesten had ridden ahead and Finan now spurred his horse to keep pace with mine.

‘So?’ I asked.

‘So are you going to be king in Mercia?’

‘The Fates say so,’ I said, not looking at him. Finan and I had been slaves together on a trader’s ship. We had suffered, frozen, endured and learned to love each other like brothers, and I cared about his opinion.

‘The Fates,’ Finan said, ‘are tricksters.’

‘Is that a Christian view?’ I asked.

He smiled. He wore his cloak’s hood over his helmet, so I could see little of his thin, feral face, but I saw the flash of teeth when he smiled. ‘I was a great man in Ireland,’ he said, ‘I had horses to outrun the wind, women to dim the sun, and weapons that could outfight the world, yet the Fates doomed me.’

‘You live,’ I said, ‘and you’re a free man.’

‘I’m your oath-man,’ he said, ‘and I gave you my oath freely. And you, lord, are Alfred’s oath-man.’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Were you forced to make your oath to Alfred?’ Finan asked.

‘No,’ I confessed.

The rain was stinging in my face. The sky was low, the land dark. ‘If fate is unavoidable,’ Finan asked, ‘why do we make oaths?’

I ignored the question. ‘If I break my oath to Alfred,’ I said instead, ‘will you break yours to me?’

‘No, lord,’ he said, smiling again. ‘I would miss your company,’ he went on, ‘but you would not miss Alfred’s.’

‘No,’ I admitted, and we let the conversation drift away with the wind-blown rain, though Finan’s words lingered in my mind and they troubled me.

We spent that night close to the great shrine of Saint Alban. The Romans had made a town there, though that town had now decayed, and so we stayed at a Danish hall just to the east. Our host was welcoming enough, but he was cautious in conversation. He did admit to hearing that Sigefrid had moved men into Lundene’s old town, but he neither condemned nor praised the act. He wore the hammer amulet, as did I, but he also kept a Saxon priest who prayed over the meal of bread, bacon and beans. The priest was a reminder that this hall was in East Anglia, and that East Anglia was officially Christian and at peace with its Christian neighbours, but our host made certain that his palisade gate was barred and that he had armed men keeping watch through the damp night. There was a shiftless air to this land, a feeling that a storm might break at any time.

The rainstorm ended in the darkness. We left at dawn, riding into a world of frost and stillness, though Wæclingastræt became busier as we encountered men driving cattle to Lundene. The beasts were scrawny, but they had been spared the autumn slaughter so they could feed the city through its winter. We rode past them and the herdsmen dropped to their knees as so many armed men clattered by. The clouds cleared to the east so that, when we came to Lundene in the middle of the day, the sun was bright behind the thick pall of dark smoke that always hangs above the city.

I have always liked Lundene. It is a place of ruins, trade and wickedness that sprawls along the northern bank of the Temes. The ruins were the buildings the Romans left when they abandoned Britain, and their old city crowned the hills at the city’s eastern end and were surrounded by a wall made of brick and stone. The Saxons had never liked the Roman buildings, fearing their ghosts, and so had made their own town to the west, a place of thatch and wood and wattle and narrow alleys and stinking ditches that were supposed to carry sewage to the river, but usually lay glistening and filthy until a downpour of rain flooded them. That new Saxon town was a busy place, stinking with the smoke from smithy fires and raucous with the shouts of tradesmen, too busy, indeed, to bother making a defensive wall. Why did they need a wall, the Saxons argued, for the Danes were content to live in the old city and had showed no desire to slaughter the inhabitants of the new. There were palisades in a few places, evidence that some men had tried to protect the rapidly growing new town, but enthusiasm for the project always died and the palisades rotted, or else their timbers were stolen to make new buildings along the sewage-stinking streets.

Lundene’s trade came from the river and from the roads that led to every part of Britain. The roads, of course, were Roman, and down them flowed wool and pottery, ingots and pelts, while the river brought luxuries from abroad and slaves from Frankia and hungry men seeking trouble. There was plenty of that, because the city, which was built where three kingdoms met, was virtually ungoverned in those years.

To the east of Lundene the land was East Anglia, and so ruled by Guthrum. To the south, on the far bank of the Temes, was Wessex, while to the west was Mercia to which the city really belonged, but Mercia was a crippled country without a king and so there was no reeve to keep order in Lundene, and no great lord to impose laws. Men went armed in the alleyways, wives had bodyguards and great dogs were chained in gateways. Bodies were found every morning, unless the tide carried them downriver towards the sea and past the coast where the Danes had their great camp at Beamfleot from where the Northmen’s ships sailed to demand customs payments from the traders working their way up the wide mouth of the Temes. The Northmen had no authority to impose such dues, but they had ships and men and swords and axes, and that was authority enough.

Haesten had exacted enough of those illegal dues, indeed he had become rich by piracy, rich and powerful, but he was still nervous as we rode into the city. He had talked incessantly as we neared Lundene, mostly about nothing, and he laughed too easily when I made sour comments about his inane words. But then, as we passed between the half-fallen towers either side of a wide gateway, he fell silent. There were sentries on the gate, but they must have recognised Haesten for they did not challenge us, but simply pulled aside the hurdles that blocked the ruined arch. Inside the arch I could see a stack of timbers that meant the gate was being rebuilt.

We had come to the Roman town, the old town, and our horses picked a slow path up the street that was paved with wide flagstones between which weeds grew thick. It was cold. Frost still lay in the dark corners where the sun had not reached the stone all day. The buildings had shuttered windows through which woodsmoke sifted to be whirled down the street. ‘You’ve been here before?’ Haesten broke his silence with the abrupt question.

‘Many times,’ I said. Haesten and I rode ahead now.

‘Sigefrid,’ Haesten said, then found he had nothing to say.

‘Is a Norseman, I hear,’ I said.

‘He is unpredictable,’ Haesten said, and the tone of his voice told me that it was Sigefrid who had made him nervous. Haesten had faced a living corpse without flinching, but the thought of Sigefrid made him apprehensive.

‘I can be unpredictable,’ I said, ‘and so can you.’

Haesten said nothing to that. Instead he touched the hammer hanging at his neck, then turned his horse into a gateway where servants ran forward to greet us. ‘The king’s palace,’ Haesten said.

I knew the palace. It had been made by the Romans and was a great vaulted building of pillars and carved stone, though it had been patched by the kings of Mercia so that thatch, wattle and timber filled the gaps in the half-ruined walls. The great hall was lined with Roman pillars and its walls were of brick, but here and there patches of marble facing had somehow survived. I stared at the high masonry and marvelled that men had ever been able to make such walls. We built in wood and thatch, and both rotted away, which meant we would leave nothing behind. The Romans had left marble and stone, brick and glory.

A steward told us that Sigefrid and his younger brother were in the old Roman arena that lay to the north of the palace. ‘What is he doing there?’ Haesten asked.

‘Making a sacrifice, lord,’ the steward said.

‘Then we’ll join him,’ Haesten said, looking at me for confirmation.

‘We will,’ I said.

We rode the short distance. Beggars shrank from us. We had money, and they knew it, but they dared not ask for it because we were armed strangers. Swords, shields, axes and spears hung beside our horses’ muddy flanks. Shopkeepers bowed to us, while women hid their children in their skirts. Most of the folk who lived in the Roman part of Lundene were Danes, yet even these Danes were nervous. Their city had been occupied by Sigefrid’s crewmen who would be hungry for money and women.

I knew the Roman arena. When I was a child I was taught the fundamental strokes of the sword by Toki the Shipmaster, and he had given me those lessons in the great oval arena that was surrounded by decayed layers of stone where wooden benches had once been placed. The tiered stone layers were almost empty, except for a few idle folk who were watching the men in the centre of the weed-choked arena. There must have been forty or fifty men there, and a score of saddled horses were tethered at the far end, but what surprised me most as I rode through the high walls of the entrance, was a Christian cross planted in the middle of the small crowd.

‘Sigefrid’s a Christian?’ I asked Haesten in astonishment.

‘No!’ Haesten said forcefully.

The men heard our hoofbeats and turned towards us. They were all dressed for war, grim in mail or leather and armed with swords or axes, but they were cheerful. Then, from the centre of that crowd, from a place close to the cross, stalked Sigefrid.

I knew him without having to be told who he was. He was a big man, and made to look even bigger for he wore a great cloak of black bear’s fur that swathed him from neck to ankles. He had tall black leather boots, a shining mail coat, a sword belt studded with silver rivets, and a bushy black beard that sprang from beneath his iron helmet that was chased with silver patterns. He pulled the helmet off as he strode towards us and his hair was as black and bushy as his beard. He had dark eyes in a broad face, a nose that had been broken and squashed, and a wide slash of a mouth that gave him a grim appearance. He stopped, facing us, and set his feet wide apart as though he waited for an attack.

‘Lord Sigefrid!’ Haesten greeted him with forced cheerfulness.

‘Lord Haesten! Welcome back! Welcome indeed.’ Sigefrid’s voice was curiously high-pitched, not feminine, but it sounded odd coming from such a huge and malevolent-looking man. ‘And you!’ he pointed a black-gloved hand towards me, ‘must be the Lord Uhtred!’

‘Uhtred of Bebbanburg,’ I named myself.

‘And you are welcome, welcome indeed!’ He stepped forward and took my reins himself, which was an honour, and then he smiled up at me and his face, that had been so fearsome, was suddenly mischievous, almost friendly. ‘They say you are tall, Lord Uhtred!’

‘So I am told,’ I said.

‘Then let us see who is taller,’ he suggested genially, ‘you or I?’ I slid from the saddle and eased the stiffness from my legs. Sigefrid, vast in his fur cloak, still held my reins and still smiled. ‘Well?’ he demanded of the men nearest to him.

‘You are taller, lord,’ one of them said hastily.

‘If I asked you who was the prettiest,’ Sigefrid said, ‘what would you say?’