По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

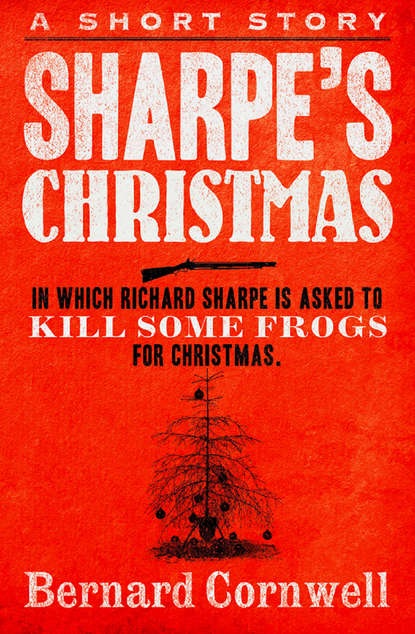

Sharpe’s Christmas

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Not all of them,” Gudin said, “some are French.”

“But French or Spanish,” Caillou insisted, “they will slow us down. The essence of success, Gudin, is to march fast. Audacity! Speed! There lies safety. We cannot take women and children.”

“If they stay,” Gudin said stubbornly, “they will be killed.”

“That’s war, Gudin, that’s war!” Caillou declared. “In war the weak die.”

“We are soldiers of France,” Gudin said stiffly, “and we do not leave women and children to die. They march with us.” Jean Gudin knew that maybe all of them, soldiers, women and children alike, might die because of that decision, but he could not abandon these Spanish women who had found themselves French husbands and given birth to half-French babies. If they were left here then the partisans would find them, they would be called traitors, they would be tortured, and they would die. No, Gudin thought, he could not just leave them. “And Maria is pregnant,” he added, nodding towards an ammunition cart on which a woman lay swathed in grey army blankets.

“I don’t care if she’s the Virgin Mary!” Caillou exploded. “We cannot afford to take women and children!” Caillou saw that his words were having no effect on the grey-haired Colonel Gudin, and the older man’s stubbornness inflamed Caillou. “My God, Gudin, no wonder they call you a failure!”

“You go too far, Colonel,” Gudin said stiffly. He outranked Caillou, but only by virtue of having been a Colonel longer than the fiery infantryman.

“I go too far?” Caillou spat in derision. “But at least I care more for France than for a pack of snivelling women. If you lose my Eagle, Gudin,” he pointed to the tricolor flag beneath its statuette of the eagle, “I will have you shot.” It was a small thing, an Eagle, hardly bigger than a man’s spread hand, but the gilded bronze birds were granted personally by Napoleon, and each held in its clawed grip the whole honour of France. To lose an Eagle was the greatest disaster a regiment could imagine, for the Emperor’s Eagle was France. “Lose it,” Caillou said savagely, “and I’ll personally command the firing squad that kills you.”

Gudin did not bother to reply, but just kicked his horse towards the gate. He felt an immense sadness. Caillou was right, he thought, he was a failure. It had all begun in India, thirteen years before, when he had been a military adviser to the Tippoo Sultan, ruler of Mysore, and Gudin had held such high hopes that, with French help and advice, the Tippoo could defeat the British in southern India, but instead the British had won. The Tippoo’s capital, Seringapatam, had fallen, and Gudin had been a prisoner for a year until he was exchanged for a British officer held prisoner by the French. He had returned to France then and thought that his career would revive, but instead it had been one long failure. He had not received one promotion in all those years, but had gone from one misfortune to the next until now he was the commander of a useless fort in a bleak landscape where France was losing a war. And if he could escape successfully? That would be a victory, especially if he could take Caillou’s precious Eagle safe across the Pyrenees, but he doubted that even an Eagle was worth the life of so many women and children. And that, he knew all too well, was his handicap. The Emperor would sacrifice a hundred thousand women and children to preserve the glory of France, but Gudin could not do it. He reached the fort’s gate and nodded to the Sergeant of the guard. “You can open up,” he said, “and once we’ve left, Sergeant, light the fuses.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: