По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

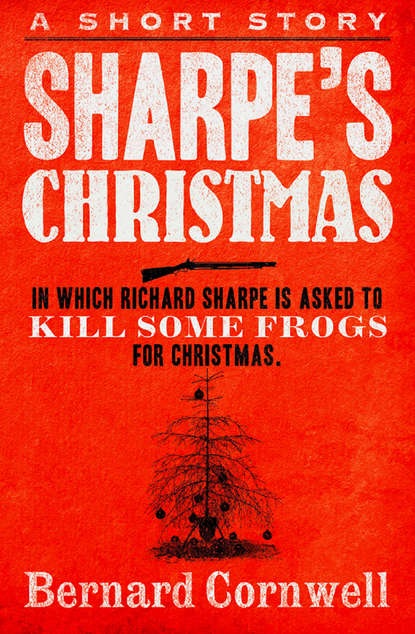

Sharpe’s Christmas

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sharpe’s Christmas

Bernard Cornwell

A Richard Sharpe short story, featuring scenes of action and adventure at Christmas.

‘You’ll like Irati,’ Colonel Hogan said. ‘It’s a nothing place, Richard. Hovels and misery, that’s all it is and all it ever will be, but that’s where you’re going for Christmas.’

Sharpe was sent to Irati because maybe the French were going there. The garrison planned to march at Christmas in the hope that their enemies would be too bloated with beef and wine to fight, but Hogan had got wind of their plans and was now setting his snares on the only two routes that the escaping French could use. One, the eastern road, was by far the easier route, for it entered France through a low pass, and Hogan guessed it was that route that the French would choose. But there was a second road, a tight, hard, steep road, and that had to be blocked as well and so the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers, Sharpe’s regiment, would climb into the hills and spend their Christmas at a place of hovels and misery called Irati.

Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

Sharpe’s Christmas

A short story

Bernard Cornwell

Copyright

While some of the events and characters are based on historical incidents and figures, this novel is entirely a work of fiction.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2011

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 1994

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

EPub Edition © 2011 ISBN: 978 0 00 723753 1

Version: 2017-05-05

Table of Contents

Cover (#ucfca540a-ed68-54f3-bff0-26061cd4d311)

Title Page (#u077dbd1b-087d-54a9-bed0-b8473937f11c)

Copyright (#uf89bfc4a-a2ee-5b49-a53a-cfeba0c0bd98)

Introduction (#ub1b0c58e-e566-59f6-951a-161d2d327b5f)

Sharpe’s Christmas (#u8799997c-6d19-5129-a20c-d3c910250f9e)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

Sharpe’s Christmas was written for the Daily Mail who needed to fill their pages over the holiday season. American readers should understand that British newspapers regard the whole of Christmas week as a vacation. Some news will make its way into the paper, but most of the staff will be at home, filling themselves with turkey, stuffing, plum pudding and brandy, and so the pages must be filled with something else. The Daily Mail was very specific; they wanted a story of 12,000 words, neatly divided into three, so they could run 4,000 words each day, and I took immense pride in delivering that requirement to a tolerance of plus or minus two words. The story is now much longer because, free of the restraints, I have taken the chance to rewrite it.

Even at the time the request seemed a bit odd to me. Sharpe, bless him, is not a man of peace. Goodwill? Yes, to those he likes, but he and Christmas are not a natural fit. It is a season, after all, when we enjoin peace on earth, it is about shepherds and babies, angels and wonder, gifts and feasting, while Sharpe is about struggle. The mismatch is almost total, but I was intrigued by the request and tried to write a tale which, while not ignoring Sharpe’s belligerent nature, nevertheless acknowledged the Christmas spirit.

For those who like to know where these stories fit into the larger scheme of Sharpe’s career, Sharpe’s Christmas falls after Sharpe’s Regiment. It is set in 1813, towards the end of the Peninsular War, but the story was written shortly after I had finished Sharpe’s Tiger, which tells of the Mysore War in India in 1799. Many of the references in Sharpe’s Christmas hark back to the events of 1799 when Sharpe briefly (and with official blessing) served in the small French force that was attempting to repel the British attack on Seringapatam, and one of the pleasures of writing it was to reintroduce Colonel Gudin, the Frenchman who was one of the first officers to spot the young Richard Sharpe’s potential.

I am most grateful to CeCe Motz, my irreplaceable assistant, who had the tiresome task of converting old newspaper pages into computer files so I could rewrite them. And I am also grateful to the Daily Mail, ever a lively newspaper, who commissioned this tale in the first place. The printed book, Sharpe’s Christmas, is available via www.bernardcornwell.net. It contains an additional story, Sharpe’s Ransom, which will be available as an ebook in 2012.

Sharpe’s Christmas

The two soldiers crouched at the edge of the field. One of them, a dark-haired man with a scarred face and hard eyes, eased back the cock of his rifle, aimed the weapon, but then, after a few seconds, lowered the gun. “Too far away,” he said softly.

The second man was even taller than the first and, like his companion, wore the faded green jacket of the 95

Rifles, but instead of a Baker rifle he carried a curious volley gun of seven barrels, each of half-inch bore and fired by a single flintlock. It was a murderous weapon, with a kick like an angry mule, but the man looked strong enough to use it. “No good trying with this,” he whispered, hefting the huge gun. “Only works at close range.”

“If we get too close they’ll run,” the first man suggested.

“Where can they run to?” the second man asked. His accent was of Ulster. “It’s a field, so it is. They can’t run away!”

“So we just walk up and shoot him?”

“Unless you want to strangle the sod, sir. Shooting’s quicker.”

Major Richard Sharpe lowered his rifle’s flint. “Come on, then,” he said, and the two men stood and walked gingerly towards the three bullocks. “You think they’ll charge us, Pat?” Sharpe asked.

“They’re gelded, sir!” Sergeant Major Patrick Harper offered. “Got about as much spunk as three blind mice.”

“They look dangerous to me,” Sharpe said. “They’ve got horns.”

“But they’re missing their other equipment, sir,” Harper said. “They can’t sing the low notes, if you follow me.” He pointed to one of the bullocks. “He’s got some rare fine fat on him, sir. He’ll roast just lovely.”

The chosen bullock, unaware of its fate, watched the two men. “I can’t just shoot it!” Sharpe protested.

“You bayoneted all those goats in Portugal, sir,” Harper pointed out, remembering a time when they had been stripping the countryside bare in front of a French advance, “so what’s different?”

“I hate goats.”

Bernard Cornwell

A Richard Sharpe short story, featuring scenes of action and adventure at Christmas.

‘You’ll like Irati,’ Colonel Hogan said. ‘It’s a nothing place, Richard. Hovels and misery, that’s all it is and all it ever will be, but that’s where you’re going for Christmas.’

Sharpe was sent to Irati because maybe the French were going there. The garrison planned to march at Christmas in the hope that their enemies would be too bloated with beef and wine to fight, but Hogan had got wind of their plans and was now setting his snares on the only two routes that the escaping French could use. One, the eastern road, was by far the easier route, for it entered France through a low pass, and Hogan guessed it was that route that the French would choose. But there was a second road, a tight, hard, steep road, and that had to be blocked as well and so the Prince of Wales’s Own Volunteers, Sharpe’s regiment, would climb into the hills and spend their Christmas at a place of hovels and misery called Irati.

Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

Sharpe’s Christmas

A short story

Bernard Cornwell

Copyright

While some of the events and characters are based on historical incidents and figures, this novel is entirely a work of fiction.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2011

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 1994

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

EPub Edition © 2011 ISBN: 978 0 00 723753 1

Version: 2017-05-05

Table of Contents

Cover (#ucfca540a-ed68-54f3-bff0-26061cd4d311)

Title Page (#u077dbd1b-087d-54a9-bed0-b8473937f11c)

Copyright (#uf89bfc4a-a2ee-5b49-a53a-cfeba0c0bd98)

Introduction (#ub1b0c58e-e566-59f6-951a-161d2d327b5f)

Sharpe’s Christmas (#u8799997c-6d19-5129-a20c-d3c910250f9e)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

Sharpe’s Christmas was written for the Daily Mail who needed to fill their pages over the holiday season. American readers should understand that British newspapers regard the whole of Christmas week as a vacation. Some news will make its way into the paper, but most of the staff will be at home, filling themselves with turkey, stuffing, plum pudding and brandy, and so the pages must be filled with something else. The Daily Mail was very specific; they wanted a story of 12,000 words, neatly divided into three, so they could run 4,000 words each day, and I took immense pride in delivering that requirement to a tolerance of plus or minus two words. The story is now much longer because, free of the restraints, I have taken the chance to rewrite it.

Even at the time the request seemed a bit odd to me. Sharpe, bless him, is not a man of peace. Goodwill? Yes, to those he likes, but he and Christmas are not a natural fit. It is a season, after all, when we enjoin peace on earth, it is about shepherds and babies, angels and wonder, gifts and feasting, while Sharpe is about struggle. The mismatch is almost total, but I was intrigued by the request and tried to write a tale which, while not ignoring Sharpe’s belligerent nature, nevertheless acknowledged the Christmas spirit.

For those who like to know where these stories fit into the larger scheme of Sharpe’s career, Sharpe’s Christmas falls after Sharpe’s Regiment. It is set in 1813, towards the end of the Peninsular War, but the story was written shortly after I had finished Sharpe’s Tiger, which tells of the Mysore War in India in 1799. Many of the references in Sharpe’s Christmas hark back to the events of 1799 when Sharpe briefly (and with official blessing) served in the small French force that was attempting to repel the British attack on Seringapatam, and one of the pleasures of writing it was to reintroduce Colonel Gudin, the Frenchman who was one of the first officers to spot the young Richard Sharpe’s potential.

I am most grateful to CeCe Motz, my irreplaceable assistant, who had the tiresome task of converting old newspaper pages into computer files so I could rewrite them. And I am also grateful to the Daily Mail, ever a lively newspaper, who commissioned this tale in the first place. The printed book, Sharpe’s Christmas, is available via www.bernardcornwell.net. It contains an additional story, Sharpe’s Ransom, which will be available as an ebook in 2012.

Sharpe’s Christmas

The two soldiers crouched at the edge of the field. One of them, a dark-haired man with a scarred face and hard eyes, eased back the cock of his rifle, aimed the weapon, but then, after a few seconds, lowered the gun. “Too far away,” he said softly.

The second man was even taller than the first and, like his companion, wore the faded green jacket of the 95

Rifles, but instead of a Baker rifle he carried a curious volley gun of seven barrels, each of half-inch bore and fired by a single flintlock. It was a murderous weapon, with a kick like an angry mule, but the man looked strong enough to use it. “No good trying with this,” he whispered, hefting the huge gun. “Only works at close range.”

“If we get too close they’ll run,” the first man suggested.

“Where can they run to?” the second man asked. His accent was of Ulster. “It’s a field, so it is. They can’t run away!”

“So we just walk up and shoot him?”

“Unless you want to strangle the sod, sir. Shooting’s quicker.”

Major Richard Sharpe lowered his rifle’s flint. “Come on, then,” he said, and the two men stood and walked gingerly towards the three bullocks. “You think they’ll charge us, Pat?” Sharpe asked.

“They’re gelded, sir!” Sergeant Major Patrick Harper offered. “Got about as much spunk as three blind mice.”

“They look dangerous to me,” Sharpe said. “They’ve got horns.”

“But they’re missing their other equipment, sir,” Harper said. “They can’t sing the low notes, if you follow me.” He pointed to one of the bullocks. “He’s got some rare fine fat on him, sir. He’ll roast just lovely.”

The chosen bullock, unaware of its fate, watched the two men. “I can’t just shoot it!” Sharpe protested.

“You bayoneted all those goats in Portugal, sir,” Harper pointed out, remembering a time when they had been stripping the countryside bare in front of a French advance, “so what’s different?”

“I hate goats.”