По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

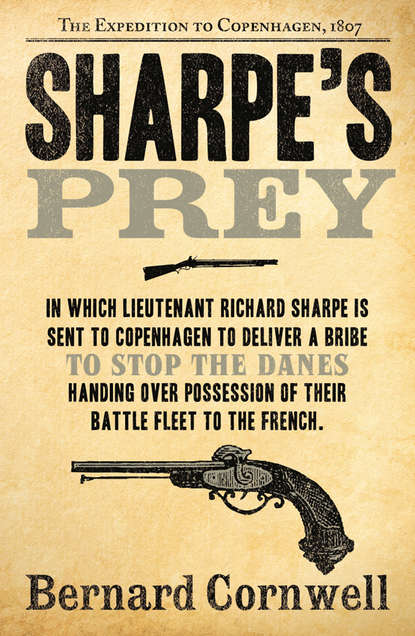

Sharpe’s Prey: The Expedition to Copenhagen, 1807

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I will, sir?’

‘They are a very trusting people,’ Lavisser said, still unable to take his gaze from Willsen’s body. ‘We shall be as ravening wolves among the woolliest of baa-lambs.’ He finally managed to look away from the corpse, raised a languid hand and edged past the handcart. He made bleating noises as he went down the alley.

The rain fell harder. It was the end of July, 1807, yet it felt more like March. It would be a poor harvest, there was a new widow in Kent and the Honourable John Lavisser went to Almack’s where he lost considerably more than a thousand guineas, but it no longer mattered. Nothing mattered now. He left worthless notes of hand promising to pay his debts and walked away. He was on his way to glory.

Mister Brown and Mister Belling, the one fat and the other thin, sat side by side and stared solemnly at the green-jacketed army officer across the table. Neither Mister Belling nor Mister Brown liked what they saw. Their visitor – he was not exactly a client – was a tall man with black hair, a hard face and a scar on his cheek and, ominously, he looked like a man who was no stranger to scars. Mister Brown sighed and turned to stare at the rain falling on London’s Eastcheap. ‘It will be a bad harvest, Mister Belling,’ he said heavily.

‘I fear so, Mister Brown.’

‘July!’ Brown said. ‘July indeed! Yet it’s more like March!’

‘A fire in July!’ Mister Belling said. ‘Unheard of!’

The fire, a mean heap of sullen coals, burned in a blackened hearth above which hung a cavalry sabre. It was the only decoration in the panelled room and hinted at the office’s military nature. Messrs Belling and Brown of Cheapside were army agents and their business was to look after the finances of officers who served abroad. They also acted as brokers for men wanting to buy or sell commissions, but this wet, chill July afternoon was bringing them no fees. ‘Alas!’ Mister Brown spread his hands. His fingers were very white, plump and beautifully manicured. He flexed them as though he was about to play a harpsichord. ‘Alas,’ he said again, looking at the green-jacketed officer who glowered from the opposite side of the table.

‘It is the nature of your commission,’ Mister Belling explained.

‘Indeed it is,’ Mister Brown intervened, ‘the nature, so to speak, of your commission.’ He smiled ruefully.

‘It’s as good as anyone else’s commission,’ the officer said belligerently.

‘Oh, better!’ Mister Brown said cheerfully. ‘Would you not agree, Mister Belling?’

‘Far better,’ Mister Belling said enthusiastically. ‘A battlefield commission, Mister Sharpe? ’Pon my soul, but that’s a rare thing. Rare!’

‘An admirable thing!’ Mister Brown added.

‘Most admirable,’ Mister Belling agreed energetically. ‘A battlefield commission! Up from the ranks! Why, it’s a …’ He paused, trying to think what it was. ‘It’s a veritable achievement!’

‘But it is not’ – Mister Brown spoke delicately, his plump hands opening and closing like a butterfly’s wings – ‘fungible.’

‘Precisely.’ Mister Belling’s manner exuded relief that his partner had found the exact word to settle the matter. ‘It is not fungible, Mister Sharpe.’

No one spoke for a few seconds. A coal hissed, rain spattered on the office window and a carter’s whip cracked in the street, which was filled with the rumble, crash and squeal of wagons and carriages.

‘Fungible?’ Lieutenant Richard Sharpe asked.

‘The commission cannot be exchanged for cash,’ Mister Belling explained. ‘You did not buy it, you cannot sell it. You were given it. What the King gives you may give back, but you cannot sell. It is not’ – he paused – ‘fungible.’

‘I was told I could sell it!’ Sharpe said angrily.

‘You were told wrong,’ Mister Brown said.

‘Misinformed,’ Mister Belling added.

‘Grievously so,’ Mister Brown said, ‘alas.’

‘The regulations are plain,’ Mister Belling went on. ‘An officer who purchases a commission is free to sell it, but a man awarded a commission is not. I wish it were otherwise.’

‘We both do!’ Mister Brown said.

‘But I was told …’

‘You were told wrong,’ Mister Belling snapped, then wished he had not spoken so brusquely for Lieutenant Sharpe started forward in his chair as though he was going to attack the two men.

Sharpe checked himself. He looked from the plump Mister Brown to the scrawny Mister Belling. ‘So there’s nothing you can do?’

Mister Belling stared at the smoke-browned ceiling for a few seconds as though seeking inspiration, then shook his head. ‘There is nothing we can do,’ he pronounced, ‘but you might apply to His Majesty’s government for a dispensation. I’ve not heard of such a course ever being followed, but an exception might be made?’ He sounded very dubious. ‘There are senior officers, perchance, who would speak for you?’

Sharpe said nothing. He had saved Sir Arthur Wellesley’s life in India, but he doubted whether the General would help him now. All Sharpe wanted was to sell his commission, take the £450 and get out of the army. But it seemed he could not sell his rank because he had not bought it.

‘Such an appeal would take time,’ Mister Brown warned him, ‘and I would not be sanguine about the outcome, Mister Sharpe. You are asking the government to set a precedent and governments are chary of precedents.’

‘Indeed they are,’ Belling said, ‘and so they should be. Though in your case … ?’ He smiled, raised his eyebrows, then sat back.

‘In my case?’ Sharpe asked, puzzled.

‘I would not be sanguine,’ Mister Brown repeated.

‘You’re saying I’m buggered?’ Sharpe asked.

‘We are saying, Mister Sharpe, that we cannot assist you.’ Mister Brown spoke severely for he had been offended by Sharpe’s language. ‘Alas.’

Sharpe gazed at the two men. Take them both down, he thought. Two minutes of bloody violence and then strip their pockets bare. The bastards must have money. And he had three shillings and threepence halfpenny in his pouch. That was it. Three shillings and threepence halfpenny.

But it was not Brown or Belling’s fault that he could not sell his commission. It was the rules. The regulations. The rich could make more money and the poor could go to hell. He stood, and the clatter of his sabre scabbard on the chair made Mister Brown wince. Sharpe draped a damp greatcoat round his shoulders, crammed a shako onto his unruly hair and picked up his pack. ‘Good day,’ he said curtly, then ducked out of the door, letting in a gust of unseasonably cold air and rain.

Mister Belling let out a great sigh of relief. ‘You know who that was, Mister Brown?’

‘He announced himself as Lieutenant Sharpe of the 95th Rifles,’ Mister Brown said, ‘and I have no reason to doubt him, do I?’

‘The very same officer, Mister Brown, who lived, or should I say cohabited, with the Lady Grace Hale!’

Mister Brown’s eyes widened. ‘No! I thought she took up with an ensign!’

Mister Belling sighed. ‘In the Rifles, Mister Brown, there are no ensigns. He is a second lieutenant. Lowest of the low!’

Mister Brown stared at the closed door. ‘’Pon my soul,’ he said softly, ‘’pon my soul!’ Here was something to tell Amelia when he got home! A scandal in the office! It had been whispered throughout London how the Lady Grace Hale, widow to a prominent man, had moved into a house with a common soldier. True, the common soldier was an officer, but not a proper officer. Not a man who had purchased his commission, but rather a sergeant who had earned a battlefield promotion, which was, in its way, entirely admirable, but even so! Lady Grace Hale, daughter of the Earl of Selby, living with a common soldier? And not just living with him, but having his baby! Or so the gossip said. The Hale family claimed the dead husband had been the child’s father and the date of the baby’s birth was conveniently within nine months of Lord William’s death, but few believed it. ‘I thought the name was somehow familiar,’ Brown said.

‘I scarcely credited it myself,’ Mister Belling admitted. ‘Can you imagine her ladyship enduring such a man? He’s scarce more than a savage!’

‘Did you note the scar on his face?’

‘And when did he last shave?’ Belling shuddered. ‘I fear he is not long for the army, Mister Brown. A curtailed career, would you not say?’

‘Truncated, Mister Belling.’

‘Penniless, no doubt!’