По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

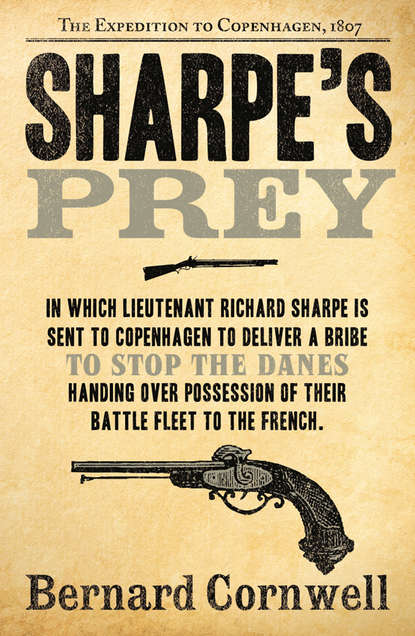

Sharpe’s Prey: The Expedition to Copenhagen, 1807

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No doubt!’ Brown said. ‘And he carried his own pack and greatcoat! An officer doesn’t carry a pack! Never seen such a thing in all my years. And he was reeking of gin.’

‘He was?’

‘Reeking!’ Brown said. ‘Well, I never! So that’s the fellow, is it? What was the Lady Grace thinking of? She must have been quite mad!’ He jumped, startled because the door had been suddenly thrown open. ‘Mister Sharpe?’ he said faintly, wondering if the tall rifleman had returned to exact vengeance for their unhelpfulness. ‘You forgot something, perhaps?’

Sharpe shook his head. ‘Today’s Friday, isn’t it?’ he asked.

Mister Belling blinked. ‘It is, Mister Sharpe,’ he said feebly, ‘it is indeed.’

‘Friday,’ Mister Brown confirmed, ‘the very last day of July.’

Sharpe, dark-eyed, tall and hard-faced, stared suspiciously at each of the two men in turn, then nodded reluctantly. ‘I thought it was,’ he said, then left again.

This time it was Brown who let out a sigh of relief as the door closed. ‘I cannot think,’ he said, ‘that promoting men from the ranks is a wise idea.’

‘It never lasts,’ Belling said consolingly, ‘they ain’t suited to rank, Mister Brown, and they take to liquor and so run out of cash. There is no prudence in the lower sort of men. He’ll be on the streets within the month, rely upon it, within the month.’

‘Poor fellow,’ Mister Brown said and shot the door’s bolt. It was only five o’clock in the evening, and the office was supposed to remain open until six, but somehow it seemed prudent to shut up early. Just in case Sharpe came back. Just in case.

Grace, Sharpe thought, Grace. God help me, Grace. God help me. Three shillings, three pence and a bloody halfpenny, all the money he had left in the world. What do I do now, Grace? He often talked to her. She was not there to listen, not now, but he still talked to her. She had taught him so much, she had encouraged him to read and tried to make him think, but nothing lasts. Nothing. ‘Bloody hell, Grace,’ he said aloud and men on the street gave him room, thinking him either mad or drunk. ‘Bloody hell.’ The anger was welling inside him, thick and dark, a fury that wanted to explode in violence or else drown itself in drink. Three shillings and threepence bloody halfpenny. He could get well drunk on that, but the ale and gin he had taken at midday was already sour in his belly. What he wanted was to hurt someone, anyone. Just a blind, desperate anger.

He had not planned it this way. He thought he would come to London, borrow an advance from an army agent, and then go away. Back to India, he had thought. Other men went there poor and came back rich. Sharpe the nabob and why not? Because he could not sell his rank, that was why not. Some snotty child with a rich father could buy and sell his rank, but a real soldier who had fought his way up the ladder could not. Bugger them all. So what now? Ebenezer Fairley, the merchant who had sailed with Sharpe from India, had offered him a job, and Sharpe supposed he could walk to Cheshire and beg from the man, but he had no urge to start that journey now. He just wanted to vent his anger and so, reassured that it was indeed Friday, he walked towards the Tower. The street stank of the river, coal smoke and horse dung. There was wealth in this part of London that lay so close to the docks and to the Custom House and to the big warehouses crammed with spices, tea and silks. This was a district of counting houses, bankers and merchants, a conduit for the world’s wealth, but the money was not displayed. A few clerks hurried from one office to another, but there were no crossing sweepers and none of the signs of luxury that filled the elegant streets to the city’s west. The buildings here were tall, dark and secret, and it was impossible to tell whether the grey-haired man scuttling with a ledger under his arm was a merchant prince or a worn-out clerk.

Sharpe turned down Tower Hill. There was a pair of red-coated sentries at the Tower’s outer gate and they pretended not to see the sabre scabbard protruding from Sharpe’s greatcoat and he pretended not to see them. He did not care if they saluted him or not. He did not much care if he never saw the army again so long as he lived. He was a failure. Storekeeper to the regiment. A bloody quartermaster. He had come from India, where he had received a commission into a red-coated regiment, to England, where he had been placed in the greenjackets, and at first he had liked the Rifles, but then Grace had gone and everything went wrong. Yet it was not her fault. Sharpe blamed himself, but still did not understand why he had failed. The Rifles were a new kind of regiment, prizing skill and intelligence above blind discipline. They worked hard, rewarded progress and encouraged the men to think for themselves. Officers trained with the men, even drilled with them, and the hours that other regiments wasted in pipe-claying and stock-polishing, in boot-licking and tuft-brushing, the green-jackets spent in rifle practice. Men and officers competed against each other, all trying to make their own company the best. It was exactly the kind of regiment that Sharpe had dreamed of when he had been in India, and he had been recommended to it. ‘I hear you’re just the sort of officer we want,’ Colonel Beckwith had greeted Sharpe, and the Colonel’s welcome was heartfelt, for Sharpe brought the green-jackets a wealth of recent experience in battle, but in the end they did not want him. He did not fit. He could not make small talk. Perhaps he had frightened them. Most of the regiment’s officers had spent the last years training on England’s south coast, while Sharpe had been fighting in India. He had become bored with the training, and after Grace he had become bitter so that the Colonel had taken him away from number three company and put him in charge of the stores. Which was where most officers up from the ranks were placed in the hidebound, red-coated regiments, but the Rifles were supposed to be different.

Now the regiment had marched away, going to fight somewhere abroad, but Sharpe, the morose quartermaster, had been left behind. ‘It’ll be a chance,’ Colonel Beckwith had told Sharpe, ‘to clean out the hutments. Give them a damn good scouring, eh? Have everything ready for our return.’

‘Yes, sir,’ Sharpe had said, and thought Beckwith could go to hell. Sharpe was a soldier, not a damned barracks cleaner, but he had hidden his anger as he watched the regiment march north. No one knew where it was going. Some said Spain, others said they were going to Stralsund, which was a British garrison on the Baltic, though why the British held a garrison on the southern coast of the Baltic no one could explain, and a few claimed the regiment was going to Holland. No one actually knew, but they all expected to fight and they marched in fine spirits. They were the greenjackets, a new regiment for a new century, but with no place for Richard Sharpe. So Sharpe had decided to run. Damn Beckwith, damn the green-jackets, damn the army and damn everything. He had reckoned he would sell his commission, take the money and find a new life. Except he could not sell because of the bloody regulations. God damn it, Grace, he thought, what do I do?

Only he knew what he was going to do. He was still going to run. Yet to start a new life he needed money, which was why he had made certain it was a Friday. Now he edged down the greasy stairs at the foot of Tower Hill and nodded to a waterman. ‘Wapping Steps,’ he said, settling in the boat’s stern.

The waterman shoved off, letting the river current carry him downstream past Traitor’s Gate. The masts were thick on either side of the river where ships and barges were double berthed against wharves crudely protected by bulging fenders made of thick, twisted, tar-soaked rope. Sharpe knew those fenders. The worn-out ones had been carted to the foundling home in Brewhouse Lane where the children had been made to dismantle the matted remnants of tar and hemp. At the age of nine, Sharpe remembered, he had lost the nails on four of his fingers. It had been useless work. Teasing out the hemp strands with small bare and bloody hands. The strands were sold as an alternative for the horsehair that stiffened the plaster used on walls. He looked at his hands now. Still rough, he thought, but no longer black with tar and bloody with ripped nails.

‘Recruiting?’ the waterman asked.

‘No.’

The curt tone might have offended the waterman, but he shrugged it off. ‘It ain’t my business,’ he said, deftly using an oar to keep the boat drifting straight, ‘but Wapping ain’t healthy. Not to an officer, sir.’

‘I grew up there.’

‘Ah,’ the man said, giving Sharpe a puzzled look. ‘Going home, then?’

‘Going home,’ Sharpe agreed. The sky was leaden with cloud and darkened further by the pall of smoke that threaded the spires and towers and masts. A black sky over a black city, broken only by a jagged streak of pink in the west. Going home, Sharpe thought. Friday evening. The small rain pitted the river. Lights glimmered from portholes in the berthed ships which stank of coal dust, sewage, whale oil and spices. Gulls flew like white scraps in the early dark, wheeling and diving about the heavy beam at Execution Dock, where the bodies of two men, mutineers or pirates, hung with broken necks.

‘Watch yourself,’ the waterman said, skilfully nudging his skiff in among the other boats at the Wapping Steps. He was not warning Sharpe against the slippery flight of stairs, but against the folk who lived in the huddled streets above.

Sharpe paid in coppers, then climbed up to the wharf which was edged with low warehouses guarded by ragged dogs and cudgel-bearing thugs. This place was safe enough, but once through the alley and into the streets he was in hungry territory. He would be back in the gutter, but it was his gutter, the place he had started and he felt no particular fear of it.

‘Colonel!’ A whore called to him from behind a warehouse. She lifted her skirt then spat a curse when Sharpe ignored her. A chained dog lunged at him as he emerged onto High Street where a dozen small boys whooped in derision at the sight of an army officer and fell into mocking step behind him. Sharpe let them follow for twenty paces, then whipped round fast and snatched the nearest boy’s shabby coat, lifted and slammed him against the wall. Two of the other boys ran off, doubtless to fetch brothers or fathers. ‘Where’s Maggie Joyce?’ Sharpe asked the boy.

The child hesitated, wondering whether to be brave, then half grinned. ‘She’s gone, mister.’

‘Gone where?’

‘Seven Dials.’

Sharpe believed him. Maggie was his one friend, or he hoped she was, but she must have had the sense to leave Wapping, though Sharpe doubted that the Seven Dials was much safer. But he had not come here to see Maggie. He had come here because it was Friday night and he was poor. ‘Who’s the Master at the workhouse?’ he asked.

The child looked really scared now. ‘The Master?’ he whispered.

‘Who is it, boy?’

‘Jem Hocking, sir.’

Sharpe put the lad down, took the halfpenny from his pocket and spun it down the street so that the boys pursued it between the people, dogs, carts and horses. Jem Hocking. That was the name he had hoped to hear. A name from a black past, a name that festered in Sharpe’s memory as he walked down the centre of the street so that no one emptied a slop bucket over his head. It was a summer evening, the cloud-hidden sun was still above the horizon, but it seemed like winter twilight here. The houses were black, their old bricks patched with crude timbers. Some had fallen down and were nothing but heaps of rubble. Cesspits stank. Dogs barked everywhere. In India the British officers had shuddered at the stench of the streets, but none had ever walked here. Even the worst street in India, Sharpe thought, was better than this foetid place where the people had pinched faces, sunk with hunger, but their eyes were bright enough, especially when they saw the pack in Sharpe’s left hand. They saw a heavy pack, a sabre and assessed the value of the greatcoat draped like a cloak over his broad shoulders. There was more wealth on Sharpe than these folk saw in a half-dozen years, though Sharpe reckoned himself poor. He had been rich once. He had taken the jewels of the Tippoo Sultan, stripping them from the dying king’s body in the shit-stinking tunnel of the Water Gate of Seringapatam, but those jewels were gone. Bloody lawyers. Bloody, bloody lawyers.

But if the folk saw the wealth on Sharpe they also saw that he was very tall and very strong and that his face was scarred and hard and bitter and forbidding. A man would have to be desperately hungry to risk his life in an attempt to steal Sharpe’s coat or pack and so, like wolves that scented blood but feared losing their own, the men watched him pass and, though some followed him as he turned up Wapping Lane, they did not pursue him into Brewhouse Lane. The poorhouse and the foundling home were there and no one went close to those grim high walls unless they were forced.

Sharpe stood in the doorway of the old brewery, long closed down, and stared across the street at the workhouse walls. On the right was the poorhouse that mostly held folk too old to work, or else they were sick or had been abandoned by their children. Landlords turned them onto the street and the parish beadle brought them here, to Jem Hocking’s kingdom, where the men were put in one ward and the women in the other. They died here, husbands forbidden to speak with their wives, and all half starved until their corpses were carried in a knacker’s cart to a pauper’s grave. That was the poorhouse, and it was divided from the foundling home by a narrow, three-storey brick house with white-painted shutters and an elegant wrought-iron lantern suspended above its well-scrubbed front steps. The Master’s house. Jem Hocking’s small palace which overlooked the foundling home which, like the poorhouse, had its own gate: a black slab of heavy timber smeared with tar and surmounted with rusted iron spikes four inches long. A prison, really, for orphans. The magistrates sent pregnant girls here, girls too poor to have a home or too sick to sell their swollen bodies on the streets. Their bastards were born here and the girls, as often as not, died of the fever. Those that survived went back to the streets, leaving their children in the tender care of Jem Hocking and his wife.

It had been Sharpe’s home once. And now it was Friday.

He crossed the street and hammered on the small wicket door set into the foundling home’s larger gate. Grace had wanted to come here. She had listened to Sharpe’s stories and believed she could change things, but there had never been time. So Sharpe would change things now. He lifted his hand to hammer again just as the wicket door opened to reveal a pale and anxious young man who flinched away from Sharpe’s fist. ‘Who are you?’ Sharpe demanded as he stepped through the small opening.

‘Sir?’ The young man had been expecting to ask that same question.

‘Who are you?’ Sharpe asked. ‘Come on, man, don’t bloody dither! And where’s the Master?’

‘The Master’s in his house, but …’ The young man abandoned whatever he had been trying to say and instead attempted to stand in front of Sharpe. ‘You can’t go in there, mister!’

‘Why not?’ Sharpe had crossed the small yard and now pushed open the door to the hall. When he had been a child he had thought it a vast room, big as a cathedral, but now it looked squalid and small. Scarce bigger than a company’s barrack room, he realized. It was supper and some thirty or more children were sitting on the floor among the oakum and the tar-encrusted fenders that was their daily work. They scooped spoons in wooden bowls while another thirty children queued beside a table that held a cauldron of soup and a bread board. A woman, her red arms massive, stood behind the table while a young man, equipped with a riding crop, lolled on the hall’s low dais above which a biblical text arched across the brown-painted wall. Be sure your sin will find you out.

Sixty pairs of eyes stared at Sharpe in astonishment. None of the children spoke for fear of the riding crop or a blow from the woman’s burly arm. Sharpe did not speak either. He was staring at the room, smelling the tar and fighting against the overwhelming memories. It had been twenty years since he had last been under this roof. Twenty years. It smelt the same, though. It smelt of tar and fear and rotten food. He stepped to the table and sniffed the soup.

‘Leek and barley gruel, sir.’ The woman, seeing the silver buttons and the black braid and the sabre, dropped a clumsy curtsey.

‘Looks like lukewarm water to me,’ Sharpe said.

‘Leek and barley, sir.’

Sharpe picked up a random piece of bread. Hard as brick. Hard as ship’s biscuit.

‘Sir?’ The woman held out her hand. She was nervous. ‘The bread is counted, sir, counted.’

Sharpe tossed it down. He was tempted to some extravagant gesture, but what would it do? Upsetting the cauldron merely meant the children would go hungry, while dropping the bread into the soup would achieve nothing. Grace would have known what to do. Her voice would have cracked like a whip and the work-house servants would have been scurrying to fetch food, clothes and soap. But those things cost money and Sharpe only had a pocketful of copper.

‘And what have we here?’ a strong voice boomed from the hall door. ‘What has the east wind blown in today?’ The children whimpered and went very still while the woman dropped another curtsey. Sharpe turned. ‘And who are you?’ the man demanded. ‘Colonel of the regiment, are you?’