По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

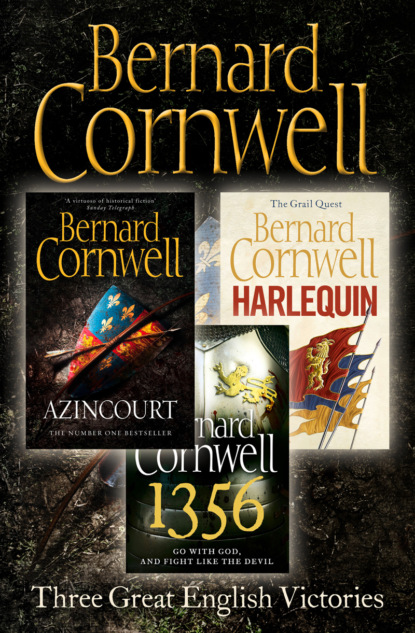

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Thomas was still crouching in the church porch. He sent an occasional arrow up towards the barbican, but the thickening smoke hung like fog and he could scarcely see his targets. He watched the men streaming off the bridge onto the narrow riverbank, but did not follow, for that seemed just another way of committing suicide. They were trapped there with the high city wall at their backs and the swirling river in front, and the far bank of the river was lined with boats from which crossbowmen poured quarrels into these new and inviting targets.

The spillage of men off the bridge opened the roadway to the barricade again and newly arrived men, who had not experienced the carnage of the first attacks, took up the fight. A hobelar managed to climb onto an overturned wagon and stabbed down with his short spear. There were crossbow bolts sticking from his chest, but still he screeched and stabbed and tried to go on fighting even when a French man-at-arms disembowelled him. His guts spilled out, but somehow he found the strength to raise the spear and give one last lunge before he fell into the defenders. A half-dozen archers were trying to dismantle the barricade, while others were throwing the dead off the bridge to clear the roadway. At least one living man, wounded, was thrown into the river. He screamed as he fell.

‘Get back, you dogs, get back!’ The Earl of Warwick had come to the chaos and he flailed at men with his marshal’s staff. He had a trumpeter sounding the four falling notes of the retreat while the French trumpeter was blasting out the attack signal, brisk couplets of rising notes that stirred the blood, and the English and Welsh were obeying the French rather than the English trumpet. More men – hundreds of them – were streaming into the old city, dodging the Earl of Warwick’s constables and closing on the bridge where, unable to get past the barricade, they followed the men down to the riverbank from where they shot their arrows at the crossbowmen in the barges. The Earl of Warwick’s men started pulling archers away from the street that led to the bridge, but for every one they hauled away another two slipped past.

A crowd of Caen’s menfolk, some armed with nothing more than staves, waited beyond the barbican, promising yet another fight if the barricade was ever overcome. A madness had gripped the English army, a madness to attack a bridge that was too well defended. Men went screaming to their deaths and still more followed. The Earl of Warwick was bellowing at them to pull back, but they were deaf to him. Then a great roar of defiance sounded from the riverbank and Thomas stepped out from the porch to see that groups of men were now trying to wade the River Odon. And they were succeeding. It had been a dry summer, the river was low and the falling tide made it lower still, so that at its deepest the water only came up to a man’s chest. Scores of men were now plunging into the river. Thomas, dodging two of the Earl’s constables, leaped the remnants of the fence and slithered down the bank, which was studded with embedded crossbow quarrels. The place stank of shit, for this was where the city emptied its nightsoil. A dozen Welsh hobelars waded into the river and Thomas joined them, holding his bow high above his head to keep its string dry. The crossbowmen had to stand up from their shelter behind the barge gunwales to shoot down at the attackers in the river, and once they were standing they made easy targets for those archers who had stayed on the city bank.

The current was strong and Thomas could only take short steps. Bolts splashed about him. A man just in front was hit in the throat and was snatched down by the weight of his mail coat to leave nothing but a swirl of bloody water. The ships’ gunwales were stuck with white-feathered arrows. A Frenchman was draped over the side of one boat and his body twitched whenever an arrow hit his corpse. Blood trickled from a scupper.

‘Kill the bastards, kill the bastards,’ a man muttered next to Thomas, who saw it was one of the Earl of Warwick’s constables; finding he could not stop the attack, he had decided to join it. The man was carrying a curved falchion, half sword and half butcher’s cleaver.

The wind flattened the smoke from the burning houses, dipping it close to the river and filling the air with scraps of burning straw. Some of those scraps had lodged in the furled sails of two of the ships that were now burning fiercely. Their defenders had scrambled ashore. Other enemy bowmen were retreating from the first mud-streaked English and Welsh soldiers who clambered up the bank between the grounded boats. The air was filled with the quick-fluttering hiss of arrows flying overhead. The island’s bells still clamoured. A Frenchman was shouting from the barbican’s tower, ordering men to spread along the river and attack the groups of Welsh and English who struggled and slithered in the river mud.

Thomas kept wading. The water reached his chest, then began to recede. He fought the clinging mud of the riverbed and ignored the crossbow bolts that drove into the water about him. A crossbowman stood up from behind a boat’s gunwale and aimed straight at Thomas’s chest, but then two arrows struck the man and he fell backwards. Thomas pushed on, climbing now. Then suddenly he was out of the river, and he stumbled up the slick mud into the shelter of the overhanging stern of the closest barge. He could see that men were still fighting at the barricade, but he could also see that the river was now swarming with archers and hobelars who, mud-spattered and soaking, began to haul themselves onto the boats. The remaining defenders had few weapons other than their crossbows, while most of the archers had swords or axes. The fight on the moored boats was one-sided, the slaughter brief, and then the disorganized and leaderless mass of attackers surged off the blood-soaked decks and up from the river onto the island.

The Earl of Warwick’s man-at-arms went ahead of Thomas. He clambered up the steep grassy bank and was immediately hit in the face by a crossbow bolt so that he jerked backwards with a fine mist of blood encircling his helmet. The bolt had driven clean through the bridge of his nose, killing him instantly and leaving him with an offended expression. His falchion landed in the mud at Thomas’s feet, so he slung his bow and picked the weapon up. It was surprisingly heavy. There was nothing sophisticated about a falchion; it was simply a killing tool with an edge designed to cut deep because of the weight of the broad blade. It was a good weapon for a mêlée. Will Skeat had once told Thomas how he had seen a Scottish horse decapitated with a single blow of a falchion, and just to see one of the brutal blades was to feel terror in the gut.

The Welsh hobelars were on the barge, finishing off its defenders, then they gave a shout in their strange language and leaped ashore and Thomas followed them, to find himself in a loose rank of crazed attackers who ran towards a row of tall and wealthy houses defended by the men who had escaped from the barges and by the citizens of Caen. The crossbowmen had time to loose one bolt apiece, but they were nervous and most shot wide, and then the attackers were onto them like hounds onto a wounded deer.

Thomas wielded the falchion two-handed. A crossbowman tried to defend himself with his bow but the heavy blade sliced through the weapon’s stock as if it had been made of ivory, then buried itself in the Frenchman’s neck. A spurt of blood jetted over Thomas’s head as he wrenched the heavy sword free and kicked the crossbowman between the legs. A Welshman was grinding a spear blade into a Frenchman’s ribs. Thomas stumbled on the man he had struck down, caught his balance and shouted the English war cry. ‘St George!’ He swung the blade again, chopping through the forearm of a man wielding a club. He was close enough to smell the man’s breath and the stink of his clothes. A Frenchman was swinging a sword while another was beating at the Welsh with an iron-studded mace. This was tavern fighting, outlaw fighting, and Thomas was screaming like a fiend. God damn them all. He was spattered with blood as he kicked and clawed and slashed his way down the alley. The air seemed unnaturally thick, moist and warm; it stank of blood. The iron-studded mace missed his head by a finger’s breadth and struck the wall instead, and Thomas swung the falchion upwards so it cut into the man’s groin. The man yelled out and Thomas kicked the back of the blade to drive it home. ‘Bastard,’ he said, kicking the blade again, ‘bastard.’ A Welshman speared the man and two more leaped his body and, their long hair and beards smeared with blood, lunged their red-bladed spears at the next rank of defenders.

There must have been twenty or more enemy in the alley, and Thomas and his companions were fewer than a dozen, but the French were nervous and the attackers were confident and so they ripped into them with spear and sword and falchion; just hacking and stabbing, slicing and cursing them, killing in a welter of summer hatred. More and more English and Welsh were swarming up from the river, and the sound they made was a keening noise, a howl for blood and a wail of derision for a wealthy enemy. These were the hounds of war that had escaped from their kennels and they were taking this great city that the lords of the army had supposed would hold the English advance for a month.

The defenders in the alley broke and ran. Thomas hacked a man down from behind and wrenched the blade free with a scraping noise of steel on bone. The hobelars kicked in a door, claiming the house beyond as their property. A rush of archers in the Prince of Wales’s green and white livery poured down the alley, following Thomas into a long and pretty garden where pear trees grew about neat plots of herbs. Thomas was struck by the incongruity of such a beautiful place under a sky filled with smoke and terrible with screams. The garden had a border of sweet rocket, wallflowers and peonies, and seats under a vine trellis and for an instant it looked like a scrap of heaven, but then the archers trampled the herbs, threw down the grape arbour and ran across the flowers.

A group of Frenchmen tried to drive the invaders out of the garden. They approached from the east, from out of the mass of men waiting behind the bridge’s barbican. They were led by three mounted men-at-arms, who all wore blue surcoats decorated with yellow stars. They jumped their horses over the low fences and shouted as they raised their long swords ready to strike.

The arrows smacked into the horses. Thomas had not unslung his bow, but some of the Prince’s archers had arrows on their cords and they aimed at the horses instead of the riders. The arrows bit deep, the horses screamed, reared and fell, and the archers swarmed over the fallen men with axes and swords. Thomas went to the right, heading off the Frenchmen on foot, most of whom seemed to be townsfolk armed with anything from small axes to thatch-hooks to ancient two-handed swords. He cut the falchion through a leather coat, kicked the blade free, swung it so that blood streamed in droplets from the blade, then hacked again. The French wavered, saw more archers coming from the alley and fled back to the barbican.

The archers were hacking at the unsaddled horsemen. One of the fallen men screamed as the blades chopped at his arms and trunk. The blue and yellow surcoats were soaked in blood. Then Thomas saw that it was not yellow stars on a blue field, but hawks. Hawks with their wings raised and their claws outstretched. Sir Guillaume d’Evecque’s men! Maybe Sir Guillaume himself! But when he looked at the grimacing, blood-spattered faces Thomas saw that all three had been young men. But Sir Guillaume was here in Caen, and the lance, Thomas thought, must be near. He broke through the fence and headed down another alley. Behind him, in the house that the hobelars had commandeered, a woman cried, the first of many. The church bells were falling silent.

Edward the Third, by the Grace of God, King of England, led close to twelve thousand fighting men and by now a fifth of them were on the island and still more were coming. No one had led them there. The only orders they had received were to retreat. But they had disobeyed and so they had captured Caen, though the enemy still held the bridge barbican from where they were spitting crossbow bolts.

Thomas emerged from the alley into the main street, where he joined a group of archers who swamped the crenellated tower with arrows and, under their cover, a howling mob of Welsh and English overwhelmed the Frenchmen cowering under the barbican’s arch before charging the defenders of the bridge barricade, who were now assailed on both sides. The Frenchmen, seeing their doom, threw down their weapons and shouted that they yielded, but the archers were in no mood for quarter. They just howled and attacked. Frenchmen were tossed into the river, and then scores of men hauled the barricade apart, tipping its furniture and wagons over the parapet.

The great mass of Frenchmen who had been waiting behind the barbican scattered into the island, most, Thomas assumed, going to rescue their wives and daughters. They were pursued by the vengeful archers who had been waiting at the bridge’s far side, and the grim crowd went past Thomas, going into the heart of the Île St Jean where the screams were now constant. The cry of havoc was everywhere. The barbican tower was still held by the French, though they were no longer using their crossbows for fear of retaliation by the English arrows. No one tried to take the tower, though a small group of archers stood in the bridge’s centre and stared up at the banners hanging from the ramparts.

Thomas was about to go into the island’s centre when he heard the clash of hooves on stone and he looked back to see a dozen French knights who must have been concealed behind the barbican. Those men now erupted from a gate and, with visors closed and lances couched, spurred their horses towards the bridge. They plainly wanted to charge clean through the old city to reach the greater safety of the castle.

Thomas took a few steps towards the Frenchmen, then thought better of it. No one wanted to resist a dozen fully armoured knights. But he saw the blue and yellow surcoat, saw the hawks on a knight’s shield and he unslung his bow and took an arrow from the bag. He hauled the cord back. The Frenchmen were just spurring onto the bridge and Thomas shouted, ‘Evecque! Evecque!’ He wanted Sir Guillaume, if it was he, to see his killer, and the man in the blue and yellow surcoat did half turn in the saddle though Thomas could not see his enemy’s face because the visor was down. He loosed, but even as he let the cord snap he saw that the arrow was warped. It flew low, smacking into the man’s left leg instead of the small of his back where Thomas had aimed. He pulled a second arrow out, but the dozen knights were on the bridge now, their horses’ hooves striking sparks from the cobbles, and the leading men lowered their lances to batter the handful of archers aside, and then they were through and galloping up the further streets towards the castle. The white-fledged arrow still jutted from the knight’s thigh where it had sunk deep and Thomas sent a second arrow after it, but that one vanished in the smoke as the French fugitives disappeared in the old city’s tight streets.

The castle had not fallen, but the city and the island belonged to the English. They did not belong to the King yet, because the great lords – the earls and the barons – had not captured either place. They belonged to the archers and the hobelars, and they now set about plundering the wealth of Caen.

The Île St Jean was, other than Paris itself, the fairest, plumpest and most elegant city in northern France. Its houses were beautiful, its gardens fragrant, its streets wide, its churches wealthy and its citizens, as they should be, civilized. Into that pleasant place came a savage horde of muddy, bloody men who found riches beyond their dreams. What the hellequin had done to countless Breton villages was now visited on a great city. It was a time for killing, for rape and wanton cruelty. Any Frenchman was an enemy, and every enemy was cut down. The leaders of the city garrison, magnates of France, were safe in the upper floors of the barbican tower and they stayed there until they recognized some English lords to whom they could safely surrender, while a dozen knights had escaped to the castle. A few other lords and knights managed to outgallop the invading English and flee across the island’s southern bridge, but at least a dozen titled men whose ransoms could have made a hundred archers rich as princelings were cut down like dogs and reduced to mangled meat and weltering blood. Knights and men-at-arms, who could have paid a hundred or two hundred pounds for their freedom, were shot with arrows or clubbed down in the mad rage which possessed the army. As for the humbler men, the citizens armed with lengths of timber, mattocks or mere knives, they were just slaughtered. Caen, the city of the Conqueror that had become rich on English plunder, was killed that day and the wealth of it was given back to Englishmen.

And not just its wealth, its women too. To be a woman in Caen that day was to be given a foretaste of hell. There was little fire, for men wanted the houses to be plundered rather than burned, but there were devils aplenty. Men begged for the honour of their wives and daughters, then were forced to watch that honour being trampled. Many women hid, but they were found soon enough by men accustomed to riddling out hiding places in attics or under stairs. The women were driven to the streets, stripped bare and paraded as trophies. One merchant’s wife, monstrously fat, was harnessed to a small cart and whipped naked up and down the main street which ran the length of the island. For an hour or more the archers made her run, some men laughing themselves to tears at the sight of her massive rolls of fat, and when they were bored with her they tossed her into the river where she crouched, weeping and calling for her children until an archer, who had been trying out a captured crossbow on a pair of swans, put a quarrel through her throat. Men laden with silver plate were staggering over the bridge, others were still searching for riches and instead found ale, cider or wine, and so the excesses grew worse. A priest was hanged from a tavern sign after he tried to stop a rape. Some men-at-arms, very few, tried to stem the horror, but they were hugely outnumbered and driven back to the bridge. The church of St Jean, which was said to contain the finger-bones of St John the Divine, a hoof of the horse St Paul was riding to Damascus and one of the baskets that had held the miraculous loaves and fishes, was turned into a brothel where the women who had fled to the church for sanctuary were sold to grinning soldiers. Men paraded in silks and lace and threw dice for the women from whom they had stolen the finery.

Thomas took no part. What happened could not be stopped, not by one man nor even by a hundred men. Another army could have quelled the mass rape, but in the end Thomas knew it would be the stupor of drunkenness that would finish it. Instead he searched for his enemy’s house, wandering from street to street until he found a dying Frenchman and gave him a drink of water before asking where Sir Guillaume d’Evecque lived. The man rolled his eyes, gasped for breath and stammered that the house was in the southern part of the island. ‘You cannot miss it,’ the man said, ‘it is stone, all stone, and has three hawks carved above the door.’

Thomas walked south. Bands of the Earl of Warwick’s men-at-arms were coming in force to the island to restore order, but they were still struggling with the archers close to the bridge, and Thomas was going to the southern part of the island which had not suffered as badly as the streets and alleys closer to the bridge. He saw the stone house above the roofs of some plundered shops. Most other buildings were half-timbered and straw-roofed, but Sir Guillaume d’Evecque’s two-storey mansion was almost a fortress. Its walls were stone, its roof tiled and its windows small, but still some archers had got inside, for Thomas could hear screams. He crossed a small square where a large oak grew through the cobbles, strode up the house steps and under an arch that was surmounted by the three carved hawks. He was surprised by the depth of anger that the sight of the escutcheon gave him. This was revenge, he told himself, for Hookton.

He went through the hallway to find a group of archers and hobelars squabbling over the kitchen pots. Two menservants lay dead by the hearth in which a fire still smouldered. One of the archers snarled at Thomas that they had reached the house first and its contents were theirs, but before Thomas could answer he heard a scream from the upper floor and he turned and ran up the big wooden stairway. Two rooms opened from the upper hallway and Thomas pushed open one of the doors to see an archer in the Prince of Wales’s livery struggling with a girl. The man had half torn off her pale blue dress, but she was fighting back like a vixen, clawing at his face and kicking his shins. Then, just as Thomas came into the room, the man managed to subdue her with a great clout to the head. The girl gasped and fell back into the wide and empty hearth as the archer turned on Thomas. ‘She’s mine,’ he said curtly, ‘go and find your own.’

Thomas looked at the girl. She was fair-haired, thin and weeping. He remembered Jeanette’s anguish after the Duke had raped her and he could not stomach seeing such pain inflicted on another girl, not even a girl in Sir Guillaume d’Evecque’s mansion.

‘I think you’ve hurt her enough,’ he said. He crossed himself, remembering his sins in Brittany. ‘Let her go,’ he added.

The archer, a bearded man a dozen years older than Thomas, drew his sword. It was an old weapon, broad-bladed and sturdy, and the man hefted it confidently. ‘Listen, boy,’ he said, ‘I’m going to watch you go through that door, and if you don’t I’ll string your goddamn guts from wall to wall.’

Thomas hefted the falchion. ‘I’ve sworn an oath to St Guinefort,’ he told the man, ‘to protect all women.’

‘Goddamn fool.’

The man leaped at Thomas, lunged, and Thomas stepped back and parried so that the blades struck sparks as they rang together. The bearded man was quick to recover, lunged again, and Thomas took another backwards step and swept the sword aside with the falchion. The girl was watching from the hearth with wide blue eyes. Thomas swung his broad blade, missed and was almost skewered by the sword, but he stepped aside just in time, then kicked the bearded man in the knee so that he hissed with pain, then Thomas swept the falchion in a great haymaking blow that cut into the bearded man’s neck. Blood arced across the room as the man, without a sound, dropped to the floor. The falchion had very nearly severed his head and the blood still pulsed from the open wound as Thomas knelt beside his victim.

‘If anyone asks,’ he said to the girl in French, ‘your father did this, then ran away.’ He had got into too much trouble after murdering a squire in Brittany and did not want to compound the crime by the death of an archer. He took four small coins from the archer’s pouch then smiled at the girl, who had remained remarkably calm while a man was almost decapitated in front of her eyes. ‘I’m not going to hurt you,’ Thomas said, ‘I promise.’

She watched him from the hearth. ‘You won’t?’

‘Not today,’ he said gently.

She stood, shaking the dizziness from her head. She pulled her dress close at her neck and tied the torn parts together with loose threads. ‘You may not hurt me,’ she said, ‘but others will.’

‘Not if you stay with me,’ Thomas said. ‘Here,’ he took the big black bow from his shoulder, unstrung it and tossed it to her. ‘Carry that,’ he said, ‘and everyone will know you’re an archer’s woman. No one will touch you then.’

She frowned at the weight of the bow. ‘No one will hurt me?’

‘Not if you carry that,’ Thomas promised her again. ‘Is this your house?’

‘I work here,’ she said.

‘For Sir Guillaume d’Evecque?’ he asked and she nodded. ‘Is he here?’

She shook her head. ‘I don’t know where he is.’

Thomas reckoned his enemy was in the castle where he would be trying to extricate an arrow from his thigh. ‘Did he keep a lance here?’ he asked. ‘A great black lance with a silver blade?’

She shook her head quickly. Thomas frowned. The girl, he could see, was trembling. She had shown bravery, but perhaps the blood seeping from the dead man’s neck was unsettling her. He also noted she was a pretty girl despite the bruises on her face and the dirt in her tangle of fair hair. She had a long face made solemn by big eyes. ‘Do you have family here?’ Thomas asked her.

‘My mother died. I have no one except Sir Guillaume.’

‘And he left you here alone?’ Thomas asked scornfully.

‘No!’ she protested. ‘He thought we’d be safe in the city, but then, when your army came, the men decided to defend the island instead. They left the city! Because all the good houses are here.’ She sounded indignant.

‘So what do you do for Sir Guillaume?’ Thomas asked her.

‘I clean,’ she said, ‘and milk the cows on the other side of the river.’ She flinched as men shouted angrily from the square outside.