По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

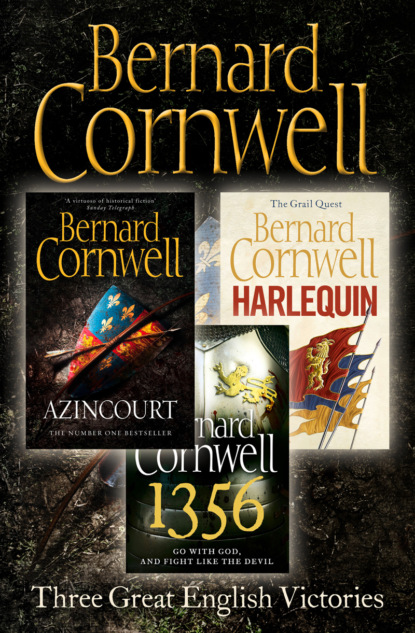

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘His name,’ Jeanette said vengefully, ‘is Sir Simon Jekyll. He tried to strip me naked, sire, and then he would have raped me if I had not been rescued. He stole my money, my armour, my horses, my ships and he would have taken my honour with as much delicacy as a wolf stealing a lamb.’

‘Is it true?’ the Prince demanded.

Sir Simon still could not speak, but the Earl of Northampton intervened. ‘The ships, armour and horses, sire, were spoils of war. I granted them to him.’

‘And the rest, Bohun?’

‘The rest, sire?’ The Earl shrugged. ‘The rest Sir Simon must explain for himself.’

‘But it seems he is speechless,’ the Prince said. ‘Have you lost your tongue, Jekyll?’

Sir Simon raised his head and caught Jeanette’s gaze, and it was so triumphant that he dropped his head again. He knew he should say something, anything, but his tongue seemed too big for his mouth and he feared he would merely stammer nonsense, so he kept silent.

‘You tried to smirch a lady’s honour,’ the Prince accused Sir Simon. Edward of Woodstock had high ideas of chivalry, for his tutors had ever read to him from the romances. He understood that war was not as gentle as the hand-written books liked to suggest, but he believed that those who were in places of honour should display it, whatever the common man might do. The Prince was also in love, another ideal encouraged by the romances. Jeanette had captivated him, and he was determined that her honour would be upheld. He spoke again, but his words were drowned by the sound of a tube gun firing. Everyone turned to stare at the castle, but the stone ball merely shattered against the gate tower, doing no damage.

‘Would you fight me for the lady’s honour?’ the Prince demanded of Sir Simon.

Sir Simon would have been happy to fight the Prince so long as he could have been assured that his victory would bring no reprisals. He knew the boy had a reputation as a warrior, yet the Prince was not full grown and nowhere near as strong or experienced as Sir Simon, but only a fool fought against a prince and expected to win. The King, it was true, entered tournaments, but he did so disguised in plain armour, without a surcoat, so that his opponents had no idea of his identity, but if Sir Simon fought the Prince then he would not dare use his full strength, for any injury done would be repaid a thousandfold by the prince’s supporters, and indeed, even as Sir Simon hesitated, the grim men behind the Prince spurred their horses forward as if offering themselves as champions for the fight. Sir Simon, overwhelmed by reality, shook his head.

‘If you will not fight,’ the Prince said in his high, clear voice, ‘then we must assume your guilt and demand recompense. You owe the lady armour and a sword.’

‘The armour was fairly taken, sire,’ the Earl of Northampton pointed out.

‘No man can take armour and weapons from a mere woman fairly,’ the Prince snapped. ‘Where is the armour now, Jekyll?’

‘Lost, sir,’ Sir Simon spoke for the first time. He wanted to tell the Prince the whole story, how Jeanette had arranged an ambush, but that tale ended with his own humiliation and he had the sense to keep quiet.

‘Then that mail coat will have to suffice,’ the Prince declared. ‘Take it off. And the sword too.’

Sir Simon gaped at the Prince, but saw he was serious. He unbuckled the sword belt and let it drop, then hauled the mail coat over his head so that he was left in his shirt and breeches.

‘What is in the pouch?’ the Prince demanded, pointing at the heavy leather bag suspended about Sir Simon’s neck.

Sir Simon sought an answer and found none but the truth, which was that the pouch was the heavy money bag he had taken from Thomas. ‘It is money, sire.’

‘Then give it to her ladyship.’

Sir Simon lifted the bag over his head and held it out to Jeanette, who smiled sweetly. ‘Thank you, Sir Simon,’ she said.

‘Your horse is forfeit too,’ the Prince decreed, ‘and you will leave this encampment by midday for you are not welcome in our company. You may go home, Jekyll, but in England you will not have our favour.’

Sir Simon looked into the Prince’s eyes for the first time. You damned miserable little pup, he thought, with your mother’s milk still sour on your unshaven lips, then he shook as he was struck by the coldness of the Prince’s eyes. He bowed, knowing he was being banished, and he knew it was unfair, but there was nothing he could do except appeal to the King, yet the King owed him no favours and no great men of the realm would speak for him, and so he was effectively an outcast. He could go home to England, but there men would soon learn he had incurred royal disfavour and his life would be endless misery. He bowed, he turned and he walked away in his dirty shirt as silent men opened a path for him.

The cannon fired on. They fired four times that day and eight the next, and at the end of the two days there was a splintered rent in the castle gate that might have given entrance to a starved sparrow. The guns had done nothing except hurt the gunners’ ears and shatter stone balls against the castle’s ramparts. Not a Frenchman had died, though one gunner and an archer had been killed when one of the brass guns exploded into a myriad red-hot scraps of metal. The King, realizing that the attempt was ridiculous, ordered the guns taken away and the siege of the castle abandoned.

And the next day the whole army left Caen. They marched eastwards, going towards Paris, and after them crawled their wagons and their camp followers and their herds of beef cattle, and for a long time afterwards the eastern sky showed white where the dust of their marching hazed the air. But at last the dust settled and the city, ravaged and sacked, was left alone. The folk who had succeeded in escaping from the island crept back to their homes. The splintered door of the castle was pushed open and its garrison came down to see what was left of Caen. For a week the priests carried an image of St Jean about the littered streets and sprinkled holy water to get rid of the lingering stink of the enemy. They said Masses for the souls of the dead, and prayed fervently that the wretched English would meet the King of France and have their own ruin visited on them.

But at least the English were gone, and the violated city, ruined, could stir again.

Light came first. A hazy light, smeared, in which Thomas thought he could see a wide window, but a shadow moved against the window and the light went. He heard voices, then they faded. In pascuis herbarum adclinavit me. The words were in his head. He makes me lie down in leafy pastures. A psalm, the same psalm from which his father had quoted his dying words. Calix meus inebrians. My cup makes me drunk. Only he was not drunk. Breathing hurt, and his chest felt as though he was being pressed by the torture of the stones. Then there was blessed darkness and oblivion once more.

The light came again. It wavered. The shadow was there, the shadow moved towards him and a cool hand was laid on his forehead.

‘I do believe you are going to live,’ a man’s voice said in a tone of surprise.

Thomas tried to speak, but only managed a strangled, grating sound.

‘It astonishes me,’ the voice went on, ‘what young men can endure. Babies too. Life is marvellously strong. Such a pity we waste it.’

‘It’s plentiful enough,’ another man said.

‘The voice of the privileged,’ the first man, whose hand was still on Thomas’s forehead, answered. ‘You take life,’ he said, ‘so value it as a thief values his victims.’

‘And you are a victim?’

‘Of course. A learned victim, a wise victim, even a valuable victim, but still a victim. And this young man, what is he?’

‘An English archer,’ the second voice said sourly, ‘and if we had any sense we’d kill him here and now.’

‘I think we shall try and feed him instead. Help me raise him.’

Hands pushed Thomas upright in the bed, and a spoonful of warm soup was put into his mouth, but he could not swallow and so spat the soup onto the blankets. Pain seared through him and the darkness came again.

The light came a third time or perhaps a fourth, he could not tell. Perhaps he dreamed it, but this time an old man stood outlined against the bright window. The man had a long black robe, but he was not a priest or monk, for the robe was not gathered at the waist and he wore a small square black hat over his long white hair.

‘God,’ Thomas tried to say, though the word came out as a guttural grunt.

The old man turned. He had a long, forked beard and was holding a jordan jar. It had a narrow neck and a round belly, and the bottle was filled with a pale yellow liquid that the man held up to the light. He peered at the liquid, then swilled it about before sniffing the jar’s mouth.

‘Are you awake?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you can speak! What a doctor I am! My brilliance astonishes me; if only it would persuade my patients to pay me. But most believe I should be grateful that they don’t spit at me. Would you say this urine is clear?’

Thomas nodded and wished he had not for the pain jarred through his neck and down his spine.

‘You do not consider it turgid? Not dark? No, indeed not. It smells and tastes healthy too. A good flask of clear yellow urine, and there is no better sign of good health. Alas, it is not yours.’ The doctor pushed open the window and poured the urine away. ‘Swallow,’ he instructed Thomas.

Thomas’s mouth was dry, but he obediently tried to swallow and immediately gasped with pain.

‘I think,’ the doctor said, ‘that we had best try a thin gruel. Very thin, with some oil, I believe, or better still, butter. That thing tied about your neck is a strip of cloth which has been soaked in holy water. It was not my doing, but I did not forbid it. You Christians believe in magic – indeed you could have no faith without a trust in magic – so I must indulge your beliefs. Is that a dog’s paw about your neck? Don’t tell me, I’m sure I don’t want to know. However, when you recover, I trust you will understand that it was neither dog paws nor wet cloths that healed you, but my skill. I have bled you, I have applied poultices of dung, moss and clove, and I have sweated you. Eleanor, though, will insist it was her prayers and that tawdry strip of wet cloth that revived you.’

‘Eleanor?’

‘She cut you down, dear boy. You were half dead. By the time I arrived you were more dead than alive and I advised her to let you expire in peace. I told her you were halfway in what you insist is hell and that I was too old and too tired to enter into a tugging contest with the devil, but Eleanor insisted and I have ever found it difficult to resist her entreaties. Gruel with rancid butter, I think. You are weak, dear boy, very weak. Do you have a name?’

‘Thomas.’