По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

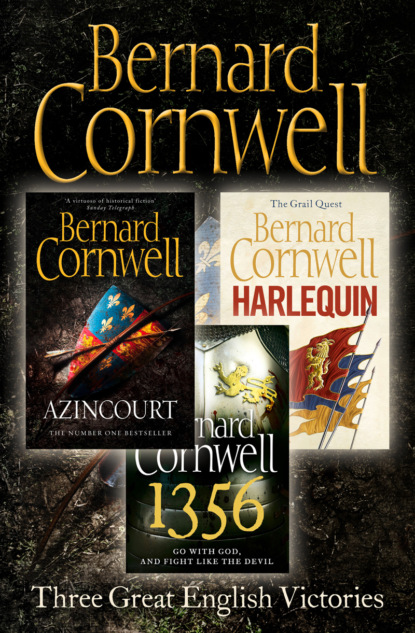

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Eleanor must have been watching for his departure, for she appeared from under the pear trees that grew at the garden’s end and gestured towards the river gate. Thomas followed her down to the bank of the River Orne where they watched an excited trio of small boys trying to spear a pike with English arrows left after the city’s capture.

‘Will you help my father?’ Eleanor asked.

‘Help him?’

‘You said his enemy was your enemy.’

Thomas sat on the grass and she sat beside him. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. He still did not really believe in any of it. There was a lance, he knew that, and a mystery about his family, but he was reluctant to admit that the lance and the mystery must govern his whole life.

‘Does that mean you’ll go back to the English army?’ Eleanor asked in a small voice.

‘I want to stay here,’ Thomas said after a pause, ‘to be with you.’

She must have known he was going to say something of the sort, but she still blushed and gazed at the swirling water where fish rose to the swarms of insects, and the three boys vainly splashed. ‘You must have a woman,’ she said softly.

‘I did,’ Thomas said, and he told her about Jeanette and how she had found the Prince of Wales and so abandoned him without a glance. ‘I will never understand her,’ he admitted.

‘But you love her?’ Eleanor asked directly.

‘No,’ Thomas said.

‘You say that because you’re with me,’ Eleanor declared.

He shook his head. ‘My father had a book of St Augustine’s sayings and there was one that always puzzled me.’ He frowned, trying to remember the Latin. ‘Nondum amabam, et amare amabam. I did not love, but yearned to love.’

Eleanor gave him a sceptical look. ‘A very elaborate way of saying you’re lonely.’

‘Yes,’ Thomas agreed.

‘So what will you do?’ she asked.

Thomas did not speak for a while. He was thinking of the penance he had been given by Father Hobbe. ‘I suppose one day I must find the man who killed my father,’ he said after a while.

‘But what if he is the devil?’ she asked seriously.

‘Then I shall wear garlic,’ Thomas said lightly, ‘and pray to St Guinefort.’

She looked at the darkening water. ‘Did St Augustine really say that thing?’

‘Nondum amabam, et amare amabam?’ Thomas said. ‘Yes, he did.’

‘I know how he felt,’ Eleanor said, and rested her head on his shoulder.

Thomas did not move. He had a choice. Follow the lance or take his black bow back to the army. In truth he did not know what he should do. But Eleanor’s body was warm against his and it was comforting and that, for the moment, was enough and so, for the moment, he would stay.

Next morning Sir Guillaume, escorted now by a half-dozen men-at-arms, took Thomas to the Abbaye aux Hommes. A crowd of petitioners stood at the gates, wanting food and clothing that the monks did not have, though the abbey itself had escaped the worst of the plundering because it had been the quarters of the King and of the Prince of Wales. The monks themselves had fled at the approach of the English army. Some had died on the Île St Jean, but most had gone south to a brother house and among those was Brother Germain who, when Sir Guillaume arrived, had just returned from his brief exile.

Brother Germain was tiny, ancient and bent, a wisp of a man with white hair, myopic eyes and delicate hands with which he was trimming a goose quill.

‘The English,’ the old man said, ‘use these feathers for their arrows. We use them for God’s word.’ Brother Germain, Thomas was told, had been in charge of the monastery’s scriptorium for more than thirty years. ‘In the course of copying books,’ the monk explained, ‘one discovers knowledge whether one wishes it or not. Most of it is quite useless, of course. How is Mordecai? He lives?’

‘He lives,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘and sends you this.’ He put a clay pot, sealed with wax, on the sloping surface of the writing desk. The pot slid down until Brother Germain trapped it and pushed it into a pouch. ‘A salve,’ Sir Guillaume explained to Thomas, ‘for Brother Germain’s joints.’

‘Which ache,’ the monk said, ‘and only Mordecai can relieve them. ’Tis a pity he will burn in hell, but in heaven, I am assured, I shall need no ointments. Who is this?’ He peered at Thomas.

‘A friend,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘who brought me this.’ He was carrying Thomas’s bow, which he now laid across the desk and tapped the silver plate. Brother Germain stooped to inspect the badge and Thomas heard a sharp intake of breath.

‘The yale,’ Brother Germain said. He pushed the bow away, then blew the scraps from his sharpened quill off the desk. ‘The beast was introduced by the heralds in the last century. Back then, of course, there was real scholarship in the world. Not like today. I get young men from Paris whose heads are stuffed with wool, yet they claim to have doctorates.’

He took a sheet of scrap parchment from a shelf, laid it on the desk and dipped his quill in a pot of vermilion ink. He let a glistening drop fall onto the parchment and then, with the skill gained in a lifetime, drew the ink out of the drop in quick strokes. He hardly seemed to be taking notice of what he was doing, but Thomas, to his amazement, saw a yale taking shape on the parchment.

‘The beast is said to be mythical,’ Brother Germain said, flicking the quill to make a tusk, ‘and maybe it is. Most heraldic beasts seem to be inventions. Who has seen a unicorn?’ He put another drop of ink on the parchment, paused a heartbeat, then began on the beast’s raised paws. ‘There is, however, a notion that the yale exists in Ethiopia. I could not say, not having travelled east of Rouen, nor have I met any traveller who has been there, if indeed Ethiopia even exists.’ He frowned. ‘The yale is mentioned by Pliny, however, which suggests it was known to the Romans, though God knows they were a credulous race. The beast is said to possess both horns and tusks, which seems extravagant, and is usually depicted as being silver with yellow spots. Alas, our pigments were stolen by the English, but they left us the vermilion which, I suppose, was kind of them. It comes from cinnabar, I’m told. Is that a plant? Father Jacques, rest his soul, always claimed it grows in the Holy Land and perhaps it does. Do I detect that you are limping, Sir Guillaume?’

‘A bastard English archer put an arrow in my leg,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘and I pray nightly that his soul will roast in hell.’

‘You should, instead, give thanks that he was inaccurate. Why do you bring me an English war bow decorated with a yale?’

‘Because I thought it would interest you,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘and because my young friend here,’ he touched Thomas’s shoulder, ‘wants to know about the Vexilles.’

‘He would do much better to forget them,’ Brother Germain grumbled.

He was perched on a tall chair and now peered about the room where a dozen young monks tidied the mess left by the monastery’s English occupiers. Some of them chattered as they worked, provoking a frown from Brother Germain.

‘This is not Caen marketplace!’ he snapped. ‘If you want to gossip, go to the lavatories. I wish I could. Ask Mordecai if he has an unguent for the bowels, would you?’ He glowered about the room for an instant, then struggled to pick up the bow that he had propped against the desk. He looked intently at the yale for an instant, then put the bow down. ‘There was always a rumour that a branch of the Vexille family went to England. This seems to confirm it.’

‘Who are they?’ Thomas asked.

Brother Germain seemed irritated by the direct question, or perhaps the whole subject of the Vexilles made him uncomfortable. ‘They were the rulers of Astarac,’ he said, ‘a county on the borders of Languedoc and the Agenais. That, of course, should tell you all you need to know of them.’

‘It tells me nothing,’ Thomas confessed.

‘Then you probably have a doctorate from Paris!’ The old man chuckled at this jest. ‘The Counts of Astarac, young man, were Cathars. Southern France was infested by that damned heresy, and Astarac was at the centre of the evil.’ He made the sign of the cross with fingers deep-stained by pigments. ‘Habere non potest,’ he said solemnly, ‘Deum patrem qui ecclesiam non habet matrem.’

‘St Cyprian,’ Thomas said. ‘‘‘He cannot have God as his father who does not have the Church as his mother.’’’

‘I see you are not from Paris after all,’ Brother Germain said. ‘The Cathars rejected the Church, looking for salvation within their own dark souls. What would become of the Church if we all did that? If we all pursued our own whims? If God is within us then we need no Church and no Holy Father to lead us to His mercy, and that notion is the most pernicious of heresies, and where did it lead the Cathars? To a life of dissipation, of fleshly lust, of pride and of perversion. They denied the divinity of Christ!’ Brother Germain made the sign of the cross again.

‘And the Vexilles were Cathars?’ Sir Guillaume prompted the old man.

‘I suspect they were devil worshippers,’ Brother Germain retorted, ‘but certainly the Counts of Astarac protected the Cathars, they and a dozen other lords. They were called the dark lords and very few of them were Perfects. The Perfects were the sect leaders, the heresiarchs, and they abstained from wine, intercourse and meat, and no Vexille would willingly abandon those three joys. But the Cathars allowed such sinners to be among their ranks and promised them the joys of heaven if they recanted before their deaths. The dark lords liked such a promise and, when the heresy was assailed by the Church, they fought bitterly.’ He shook his head. ‘This was a hundred years ago! The Holy Father and the King of France destroyed the Cathars, and Astarac was one of the last fortresses to fall. The fight was dreadful, the dead innumerable, but the heresiarchs and the dark lords were finally scotched.’

‘Yet some escaped?’ Sir Guillaume suggested gently.

Brother Germain was silent for a while, gazing at the drying vermilion ink. ‘There was a story,’ he said, ‘that some of the Cathar lords did survive, and that they took their riches to countries all across Europe. There is even a rumour that the heresy yet survives, hidden in the lands where Burgundy and the Italian states meet.’ He made the sign of the cross. ‘I think a part of the Vexille family went to England, to hide there, for it was in England, Sir Guillaume, that you found the lance of St George. Vexille …’ He said the name thoughtfully. ‘It derives, of course, from vexillaire, a standard-bearer, and it is said that an early Vexille discovered the lance while on the crusades and thereafter carried it as a standard. It was certainly a symbol of power in those old days. Myself? I am sceptical of these relics. The abbot assures me he has seen three foreskins of the infant Jesus and even I, who hold Him blessed above all things, doubt He was so richly endowed, but I have asked some questions about this lance. There is a legend attached to it. It is said that the man who carries the lance into battle cannot be defeated. Mere legend, of course, but belief in such nonsense inspires the ignorant, and there are few more ignorant than soldiers. What troubles me most, though, is their purpose.’

‘Whose purpose?’ Thomas asked.

‘There is a story,’ Brother Germain said, ignoring the question, ‘that before the fall of the last heretic fortresses, the surviving dark lords made an oath. They knew the war was lost, they knew their strongholds must fall and that the Inquisition and the forces of God would destroy their people, and so they made an oath to visit vengeance on their enemies. One day, they swore, they would bring down the Throne of France and the Holy Mother Church, and to do it they would use the power of their holiest relics.’