По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

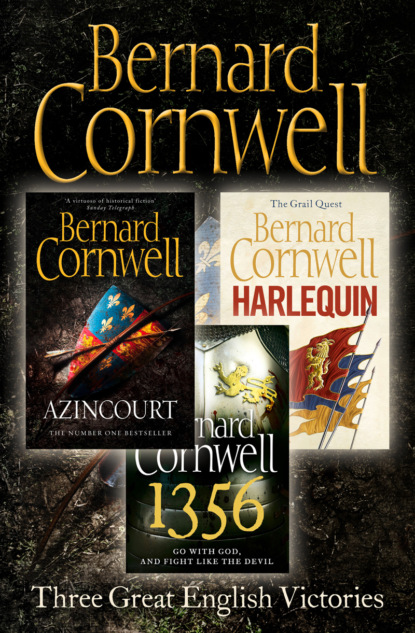

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The lance of St George?’ Thomas asked.

‘That too,’ Brother Germain said.

‘That too?’ Sir Guillaume repeated the words in a puzzled tone.

Brother Germain dipped his quill and put another glistening drop of ink on the parchment. Then, deftly, he finished his copy of the badge on Thomas’s bow. ‘The yale,’ he said, ‘I have seen before, but the badge you showed me is different. The beast is holding a chalice. But not any chalice, Sir Guillaume. You are right, the bow interests me, and frightens me, for the yale is holding the Grail. The holy, blessed and most precious Grail. It was always rumoured that the Cathars possessed the Grail. There is a tawdry lump of green glass in Genoa Cathedral that is said to be the Grail, but I doubt our dear Lord drank from such a bauble. No, the real Grail exists, and whoever holds it possesses power above all men on earth.’ He put down the quill. ‘I fear, Sir Guillaume, that the dark lords want their revenge. They gather their strength. But they hide still and the Church has not yet taken notice. Nor will it until the danger is obvious, and by then it will be too late.’ Brother Germain lowered his head so that Thomas could only see the bald pink patch among the white hair. ‘It is all prophesied,’ the monk said; ‘it is all in the books.’

‘What books?’ Sir Guillaume asked.

‘Et confortabitur rex austri et de principibus eius praevalebit super eum,’ Brother Germain said softly.

Sir Guillaume looked quizzically at Thomas. ‘And the King from the south will be mighty,’ Thomas reluctantly translated, ‘but one of his princes will be stronger than him.’

‘The Cathars are of the south,’ Brother Germain said, ‘and the prophet Daniel foresaw it all.’ He raised his pigment-stained hands. ‘The fight will be terrible, for the soul of the world is at stake, and they will use any weapon, even a woman. Filiaque regis austri veniet ad regem aquilonis facere amicitiam.’

‘The daughter of the King of the south,’ Thomas said, ‘shall come to the King of the north and make a treaty.’

Brother Germain heard the distaste in Thomas’s voice. ‘You don’t believe it?’ he hissed. ‘Why do you think we keep the scriptures from the ignorant? They contain all sorts of prophecies, young man, and each of them given direct to us by God, but such knowledge is confusing to the unlearned. Men go mad when they know too much.’ He made the sign of the cross. ‘I thank God I shall be dead soon and taken to the bliss above while you must struggle with this darkness.’

Thomas walked to the window and watched two wagons of grain being unloaded by novices. Sir Guillaume’s men-at-arms were playing dice in the cloister. That was real, he thought, not some babbling prophet. His father had ever warned him against prophecy. It drives men’s minds awry, he had said, and was that why his own mind had gone astray?

‘The lance,’ Thomas said, trying to cling to fact instead of fancy, ‘was taken to England by the Vexille family. My father was one of them, but he fell out with the family and he stole the lance and hid it in his church. He was killed there, and at his death he told me it was his brother’s son who did it. I think it is that man, my cousin, who called himself the Harlequin.’ He turned to look at Brother Germain. ‘My father was a Vexille, but he was no heretic. He was a sinner, yes, but he struggled against his sin, he hated his own father, and he was a loyal son of the Church.’

‘He was a priest,’ Sir Guillaume explained to the monk.

‘And you are his son?’ Brother Germain asked in a disapproving tone. The other monks had abandoned their tidying and were listening avidly.

‘I am a priest’s son,’ Thomas said, ‘and a good Christian.’

‘So the family discovered where the lance was hidden,’ Sir Guillaume took up the story, ‘and hired me to retrieve it. But forgot to pay me.’

Brother Germain appeared not to have heard. He was staring at Thomas. ‘You are English?’

‘The bow is mine,’ Thomas acknowledged.

‘So you are a Vexille?’

Thomas shrugged. ‘It would seem so.’

‘Then you are one of the dark lords,’ Brother Germain said.

Thomas shook his head. ‘I am a Christian,’ he said firmly.

‘Then you have a God-given duty,’ the small man said with surprising force, ‘which is to finish the work that was left undone a hundred years ago. Kill them all! Kill them! And kill the woman. You hear me, boy? Kill the daughter of the King of the south before she seduces France to heresy and wickedness.’

‘If we can even find the Vexilles,’ Sir Guillaume said dubiously, and Thomas noted the word ‘we’. ‘They don’t display their badge. I doubt they use the name Vexille. They hide.’

‘But they have the lance now,’ Brother Germain said, ‘and they will use it for the first of their vengeances. They will destroy France, and in the chaos that ensues, they will attack the Church.’ He moaned, as if he was in physical pain. ‘You must take away their power, and their power is the Grail.’

So it was not just the lance that Thomas must save. To Father Hobbe’s charge had been added all of Christendom. He wanted to laugh. Catharism had died a hundred years before, scourged and burned and dug out of the land like couch grass grubbed from a field! Dark lords, daughters of kings and princes of darkness were figments of the troubadours, not the business of archers. Except that when he looked at Sir Guillaume he saw that the Frenchman was not mocking the task. He was staring at a crucifix hanging on the scriptorium wall and mouthing a silent prayer. God help me, Thomas thought, God help me, but I am being asked to do what all the great knights of Arthur’s round table failed to do: to find the Grail.

Philip of Valois, King of France, ordered every Frenchman of military age to gather at Rouen. Demands went to his vassals and appeals were carried to his allies. He had expected the walls of Caen to hold the English for weeks, but the city had fallen in a day and the panicked survivors were spreading across northern France with terrible stories of devils unleashed.

Rouen, nestled in a great loop of the Seine, filled with warriors. Thousands of Genoese crossbowmen came by galley, beaching their ships on the river’s bank and thronging the city’s taverns, while knights and men-at-arms arrived from Anjou and Picardy, from Alençon and Champagne, from Maine, Touraine and Berry. Every blacksmith’s shop became an armoury, every house a barracks and every tavern a brothel. More men arrived, until the city could scarce contain them, and tents had to be set up in the fields south of the city. Wagons crossed the bridge, loaded with hay and newly harvested grain from the rich farmlands north of the river, while from the Seine’s southern bank came rumours. The English had taken Evreux, or perhaps it was Bernay? Smoke had been seen at Lisieux, and archers were swarming through the forest of Brotonne. A nun in Louviers had a dream in which the dragon killed St George. King Philip ordered the woman brought to Rouen, but she had a harelip, a hunchback and a stammer, and when she was presented to the King she proved unable to recount the dream, let alone confide God’s strategy to His Majesty. She just shuddered and wept and the King dismissed her angrily, but took consolation from the bishop’s astrologer who said Mars was in the ascendant and that meant victory was certain.

Rumour said the English were marching on Paris, then another rumour claimed they were going south to protect their territories in Gascony. It was said that every person in Caen had died, that the castle was rubble; then a story went about that the English themselves were dying of a sickness. King Philip, ever a nervous man, became petulant, demanding news, but his advisers persuaded their irritable master that wherever the English were they must eventually starve if they were kept south of the great River Seine that twisted like a snake from Paris to the sea. Edward’s men were wasting the land, so needed to keep moving if they were to find food, and if the Seine was blocked then they could not go north towards the harbours on the Channel coast where they might expect supplies from England.

‘They use arrows like a woman uses money,’ Charles, the Count of Alençon and the King’s younger brother, advised Philip, ‘but they cannot fetch their arrows from France. They are brought to them by sea, and the further they go from the sea, the greater their problems.’ So if the English were kept south of the Seine then they must eventually fight or make an ignominious retreat to Normandy.

‘What of Paris? Paris? What of Paris?’ the King demanded.

‘Paris will not fall,’ the Count assured his brother. The city lay north of the Seine, so the English would need to cross the river and assault the largest ramparts in Christendom, and all the while the garrison would be showering them with crossbow bolts and the missiles from the hundreds of small iron guns that had been mounted on the city walls.

‘Maybe they will go south?’ Philip worried. ‘To Gascony?’

‘If they march to Gascony,’ the Count said, ‘then they will have no boots by the time they arrive, and their arrow store will be gone. Let us pray they do go to Gascony, but above all things pray they do not reach the Seine’s northern bank.’ For if the English crossed the Seine they would go to the nearest Channel port to receive reinforcements and supplies and, by now, the Count knew, the English would be needing supplies. A marching army tired itself, its men became sick and its horses lame. An army that marched too long would eventually wear out like a tired crossbow.

So the French reinforced the great fortresses that guarded the Seine’s crossings and where a bridge could not be guarded, such as the sixteen-arched bridge at Poissy, it was demolished. A hundred men with sledgehammers broke down the parapets and hammered the stonework of the arches into the river to leave the fifteen stumps of the broken piers studding the Seine like the stepping stones of a giant, while Poissy itself, which lay south of the Seine and was reckoned indefensible, was abandoned and its people evacuated to Paris. The wide river was being turned into an impassable barrier to trap the English in an area where their food must eventually run short. Then, when the devils were weakened, the French would punish them for the terrible damage they had wrought on France. The English were still burning towns and destroying farms so that, in those long summer days, the western and southern horizons were so smeared by smoke plumes that it seemed as if there were permanent clouds on the skylines. At night the world’s edge glowed and folk fleeing the fires came to Rouen where, because so many could not be housed or fed, they were ordered across the river and away to wherever they might find shelter.

Sir Simon Jekyll, and Henry Colley, his man-at-arms, were among the fugitives, and they were not refused admittance, for they both rode destriers and were in mail. Colley wore his own mail and rode his own horse, but Sir Simon’s mount and gear had been stolen from one of his other men-at-arms before he fled from Caen. Both men carried shields, but they had stripped the leather covers from the willow boards so that the shields bore no device, thus declaring themselves to be masterless men for hire. Scores like them came to the city, seeking a lord who could offer food and pay, but none arrived with the anger that filled Sir Simon.

It was the injustice that galled him. It burned his soul, giving him a lust for revenge. He had come so close to paying all his debts – indeed, when the money from the sale of Jeanette’s ships was paid from England he had expected to be free of all encumbrances – but now he was a fugitive. He knew he could have slunk back to England, but any man out of favour with the King or the King’s eldest son could expect to be treated as a rebel, and he would be fortunate if he kept an acre of land, let alone his freedom. So he had preferred flight, trusting that his sword would win back the privileges he had lost to the Breton bitch and her puppy lover, and Henry Colley had ridden with him in the belief that any man as skilled in arms as Sir Simon could not fail.

No one questioned their presence in Rouen. Sir Simon’s French was tinged with the accent of England’s gentry, but so was the French of a score of other men from Normandy. What Sir Simon needed now was a patron, a man who would feed him and give him the chance to fight back against his persecutors, and there were plenty of great men looking for followers. In the fields south of Rouen, where the looping river narrowed the land, a pasture had been set aside as a tourney ground where, in front of a knowing crowd of men-at-arms, anyone could enter the lists to show their prowess. This was not a serious tournament – the swords were blunt and lances were tipped with wooden blocks – but rather it was a chance for masterless men to show their prowess with weapons, and a score of knights, the champions of dukes, counts, viscounts and mere lords, were the judges. Dozens of hopeful men were entering the lists, and any horseman who could last more than a few minutes against the well-mounted and superbly armed champions was sure to find a place in the entourage of a great nobleman.

Sir Simon, on his stolen horse and with his ancient battered sword, was one of the least impressive men to ride into the pasture. He had no lance, so one of the champions drew a sword and rode to finish him off. At first no one took particular notice of the two men for other combats were taking place, but when the champion was sprawling on the grass and Sir Simon, untouched, rode on, the crowd took notice.

A second champion challenged Sir Simon and was startled by the fury which confronted him. He called out that the combat was not to the death, but merely a demonstration of swordplay, but Sir Simon gritted his teeth and hacked with the sword so savagely that the champion spurred and wheeled his horse away rather than risk injury. Sir Simon turned his horse in the pasture’s centre, daring another man to face him, but instead a squire trotted a mare to the field’s centre and wordlessly offered the Englishman a lance.

‘Who sent it?’ Sir Simon demanded.

‘My lord.’

‘Who is?’

‘There,’ the squire said, pointing to the pasture’s end where a tall man in black armour and riding a black horse waited with his lance.

Sir Simon sheathed his sword and took the lance. It was heavy and not well balanced, and he had no lance rest in his armour that would cradle the long butt to help keep the point raised, but he was a strong man and an angry one, and he reckoned he could manage the cumbersome weapon long enough to break the stranger’s confidence.

No other men fought on the field now. They just watched. Wagers were being made and all of them favoured the man in black. Most of the onlookers had seen him fight before, and his horse, his armour and his weapons were all plainly superior. He wore plate mail and his horse stood at least a hand’s breadth taller than Sir Simon’s sorry mount. His visor was down, so Sir Simon could not see the man’s face, while Sir Simon himself had no faceplate, merely an old, cheap helmet like those worn by England’s archers. Only Henry Colley laid a bet on Sir Simon, though he had difficulty in doing it for his French was rudimentary, but the money was at last taken.

The stranger’s shield was black and decorated with a simple white cross, a device unknown to Sir Simon, while his horse had a black trapper that swept the pasture as the beast began to walk. That was the only signal the stranger gave and Sir Simon responded by lowering the lance and kicking his own horse forward. They were a hundred paces apart and both men moved swiftly into the canter. Sir Simon watched his opponent’s lance, judging how firmly it was held. The man was good, for the lance tip scarcely wavered despite the horse’s uneven motion. The shield was covering his trunk, as it should be.

If this had been a battle, if the man with the strange shield had not offered Sir Simon a chance of advancement, he might have lowered his own lance to strike his opponent’s horse. Or, a more difficult strike, thrust the weapon’s tip into the high pommel of his saddle. Sir Simon had seen a lance go clean through the wood and leather of a saddle to gouge into a man’s groin, and it was ever a killing blow. But today he was required to show the skill of a knight, to strike clean and hard, and at the same time defend himself from the oncoming lance. The skill of that was to deflect the thrust which, having the weight of a horse behind it, could break a man’s back by throwing him against the high cantle. The shock of two heavy horsemen meeting, and with all their weight concentrated into lance points, was like being hit by a cannon’s stone.

Sir Simon was not thinking about any of this. He was watching the oncoming lance, glancing at the white cross on the shield where his own lance was aimed, and guiding his horse with pressure from his knees. He had trained to this from the time he could first sit on a pony. He had spent hours tilting at a quintain in his father’s yard, and more hours schooling stallions to endure the noise and chaos of battle. He moved his horse slightly to the left like a man wanting to widen the angle at which the lances would strike and so deflect some of their force, and he noted that the stranger did not follow the move to straighten the line, but seemed happy to accept the lesser risk. Then both men rowelled back their spurs and the destriers went into the gallop. Sir Simon touched the horse’s right side and straightened the line himself, driving hard at the stranger now, and leaning slightly forward to ready himself for the blow. His opponent was trying to swing towards him, but it was too late. Sir Simon’s lance cracked against the black and white shield with a thump that hurled Sir Simon back, but the stranger’s lance was not centred and banged against Sir Simon’s plain shield and glanced off.

Sir Simon’s lance broke into three pieces and he let it fall as he pressed his knee to turn the horse. His opponent’s lance was across his body now and was encumbering the black-armoured knight. Sir Simon drew his sword and, while the other man was still trying to rid himself of the lance, gave a backswing that struck his opponent like a hammer blow.