По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

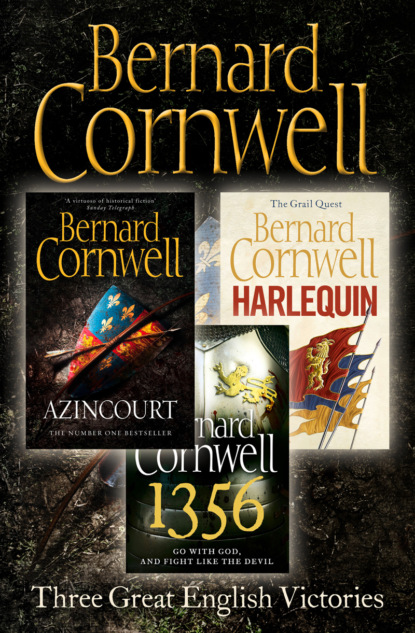

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sir Guillaume sneered. ‘You’re Cathar, you’re French, you’re from Languedoc, who knows what you are? You’re a priest’s son, a mongrel bastard of heretic stock.’

‘I’m English,’ Thomas said.

‘You’re a Christian,’ Sir Guillaume retorted, ‘and God has given you and me a duty. How are you to fulfil that duty by joining Edward’s army?’

Thomas did not answer at once. Had God given him a duty? If so he did not want to accept it, for acceptance meant believing in the legends of the Vexilles. Thomas, in the evening after he had met Brother Germain, had talked with Mordecai in Sir Guillaume’s garden, asking the old man if he had ever read the book of Daniel.

Mordecai had sighed, as if he found the question wearisome. ‘Years ago,’ he’d said, ‘many years ago. It is part of the Ketuvim, the writings that all Jewish youths must read. Why?’

‘He’s a prophet, yes? He tells the future.’

‘Dear me,’ Mordecai had said, sitting on the bench and dragging his thin fingers through his forked beard. ‘You Christians,’ he had said, ‘insist that prophets tell the future, but that wasn’t really what they did at all. They warned Israel. They told us that we would be visited by death, destruction and horror if we did not mend our ways. They were preachers, Thomas, just preachers, though, God knows, they were right about the death, destruction and horror. As for Daniel … He is very strange, very strange. He had a head filled with dreams and visions. He was drunk on God, that one.’

‘But do you think,’ Thomas had asked, ‘that Daniel could foretell what is happening now?’

Mordecai had frowned. ‘If God wished him to, yes, but why should God wish that? And I assume, Thomas, that you think Daniel might foretell what happens here and now in France, and what possible interest could that hold for the God of Israel? The Ketuvim are full of fancy, vision and mystery, and you Christians see more in them than we ever did. But would I make a decision because Daniel ate a bad oyster and had a vivid dream all those years ago? No, no, no.’ He stood and held a jordan bottle high. ‘Trust what is before your eyes, Thomas, what you can smell, hear, taste, touch and see. The rest is dangerous.’

Thomas now looked at Sir Guillaume. He had come to like the Frenchman whose battle-hardened exterior hid a wealth of kindness, and Thomas knew he was in love with the Frenchman’s daughter, but, even so, he had a greater loyalty.

‘I cannot fight against England,’ he said, ‘any more than you would carry a lance against King Philip.’

Sir Guillaume dismissed that with a shrug. ‘Then fight against the Vexilles.’

But Thomas could not smell, hear, taste, touch or see the Vexilles. He did not believe the king of the south would send his daughter to the north. He did not believe the Holy Grail was hidden in some heretic’s fastness. He believed in the strength of a yew bow, the tension of a hemp cord and the power of a white-feathered arrow to kill the King’s enemies. To think of dark lords and of heresiarchs was to flirt with the madness that had harrowed his own father.

‘If I find the man who killed my father,’ he evaded Sir Guillaume’s demand, ‘then I will kill him.’

‘But you will not search for him?’

‘Where do I look? Where do you look?’ Thomas asked, then offered his own answer. ‘If the Vexilles really still exist, if they truly want to destroy France, then where would they begin? In England’s army. So I shall look for them there.’ That answer was an evasion, but it half convinced Sir Guillaume, who grudgingly conceded that the Vexilles might indeed take their forces to Edward of England.

That night they sheltered in the scorched remains of a farm where they gathered about a small fire on which they roasted the hind legs of a boar that Thomas had shot. The men-at-arms treated Thomas warily. He was, after all, one of the hated English archers whose bows could pierce even plate mail. If he had not been Sir Guillaume’s friend they would have wanted to slice off his string fingers in revenge for the pain that the white-fledged arrows had given to the horsemen of France, but instead they treated him with a distant curiosity. After the meal Sir Guillaume gestured to Eleanor and Thomas that they should both accompany him outside. His squire was keeping watch, and Sir Guillaume led them away from the young man, going to the bank of a stream where, with an odd formality, he looked at Thomas. ‘So you will leave us,’ he said, ‘and fight for Edward of England.’

‘Yes.’

‘But if you see my enemy, if you see the lance, what will you do?’

‘Kill him,’ Thomas said. Eleanor stood slightly apart, watching and listening.

‘He will not be alone,’ Sir Guillaume warned, ‘but you assure me he is your enemy?’

‘I swear it,’ Thomas said, puzzled that the question even needed to be asked.

Sir Guillaume took Thomas’s right hand. ‘You have heard of a brotherhood in arms?’

Thomas nodded. Men of rank frequently made such pacts, swearing to aid each other in battle and share each other’s spoils.

‘Then I swear a brotherhood to you,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘even if we will fight on opposing sides.’

‘I swear the same,’ Thomas said awkwardly.

Sir Guillaume let Thomas’s hand go. ‘There,’ he said to Eleanor, ‘I’m safe from one damned archer.’ He paused, still looking at Eleanor. ‘I shall marry again,’ he said abruptly, ‘and have children again and they will be my heirs. You know what I’m saying, don’t you?’

Eleanor’s head was lowered, but she looked up at her father briefly, then dropped her gaze again. She said nothing.

‘And if I have more children, God willing,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘what does that leave for you, Eleanor?’

She gave a very small shrug as if to suggest that the question was not of great interest to her. ‘I have never asked you for anything.’

‘But what would you have asked for?’

She stared into the ripples of the stream. ‘What you gave me,’ she said after a while, ‘kindness.’

‘Nothing else?’

She paused. ‘I would have liked to call you Father.’

Sir Guillaume seemed uncomfortable with that answer. He stared northwards. ‘You are both bastards,’ he said after a while, ‘and I envy that.’

‘Envy?’ Thomas asked.

‘A family serves like the banks of a stream. They keep you in your place, but bastards make their own way. They take nothing and they can go anywhere.’ He frowned, then flicked a pebble into the water. ‘I had always thought, Eleanor, that I would marry you to one of my men-at-arms. Benoit asked me for your hand and so did Fossat. And it’s past time you were married. What are you? Fifteen?’

‘Fifteen,’ she agreed.

‘You’ll rot away, girl, if you wait any longer,’ Sir Guillaume said gruffly, ‘so who shall it be? Benoit? Fossat?’ He paused. ‘Or would you prefer Thomas?’

Eleanor said nothing and Thomas, embarrassed, kept silent.

‘You want her?’ Sir Guillaume asked him brutally.

‘Yes.’

‘Eleanor?’

She looked at Thomas, then back to the stream. ‘Yes,’ she said simply.

‘The horse, the mail, the sword and the money,’ Sir Guillaume said to Thomas, ‘are my bastard daughter’s dowry. Look after her, or else become my enemy again.’ He turned away.

‘Sir Guillaume?’ Thomas asked. The Frenchman turned back. ‘When you went to Hookton,’ Thomas went on, wondering why he asked the question now, ‘you took a dark-haired girl prisoner. She was pregnant. Her name was Jane.’

Sir Guillaume nodded. ‘She married one of my men. Then died in childbirth. The child too. Why?’ He frowned. ‘Was the child yours?’

‘She was a friend,’ Thomas evaded the question.

‘She was a pretty friend,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘I remember that. And when she died we had twelve Masses said for her English soul.’

‘Thank you.’