По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

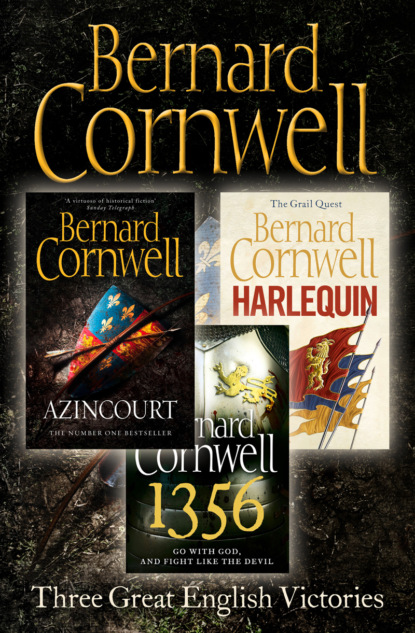

Three Great English Victories: A 3-book Collection of Harlequin, 1356 and Azincourt

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sir Guillaume looked from Thomas to Eleanor, then back to Thomas. ‘A good night for sleeping under the stars,’ he said, ‘and we shall leave at dawn.’ He walked away.

Thomas and Eleanor sat by the stream. The sky was still not wholly dark, but had a luminous quality like the glow of a candle behind horn. An otter slid down the far side of the stream, its fur glistening where it showed above the water. It raised its head, looked briefly at Thomas, then dived out of sight, to leave a trickle of silver bubbles breaking the dark surface.

Eleanor broke the silence, speaking the only English words she knew. ‘I am an archer’s woman,’ she said.

Thomas smiled. ‘Yes,’ he said.

And in the morning they rode on and next evening they saw the smear of smoke on the northern horizon and knew it was a sign that the English army was going about its business. They parted in the next dawn.

‘How you reach the bastards, I do not know,’ Sir Guillaume said, ‘but when it is all over, look for me.’

He embraced Thomas, kissed Eleanor, then pulled himself into his saddle. His horse had a long blue trapper decorated with yellow hawks. He settled his right foot into its stirrup, gathered the reins and pushed back his spurs.

A track led north across a heath that was fragrant with thyme and fluttering with blue butterflies. Thomas, his helmet hanging from the saddle’s pommel and the sword thumping at his side, rode towards the smoke, and Eleanor, who insisted on carrying his bow because she was an archer’s woman, rode with him. They looked back from the low crest of the heath, but Sir Guillaume was already a half-mile westwards, not looking back, hurrying towards the oriflamme.

So Thomas and Eleanor rode on.

The English marched east, ever further from the sea, searching for a place to cross the Seine, but every bridge was broken or else was guarded by a fortress. They still destroyed everything they touched. Their chevauchée was a line twenty miles wide and behind it was a charred trail a hundred miles long. Every house was burned and every mill destroyed. The folk of France fled from the army, taking their livestock and the newly gathered harvest with them so that Edward’s men had to range ever further to find food. Behind them was desolation while in front lay the formidable walls of Paris. Some men thought the King would assault Paris, others reckoned he would not waste his troops on those great walls, but instead attack one of the strongly fortified bridges that could lead him north of the river. Indeed, the army tried to capture the bridge at Meulan, but the stronghold which guarded its southern end was too massive and its crossbowmen were too many, and the assault failed. The French stood on the ramparts and bared their backsides to insult the defeated English. It was said that the King, confident of crossing the river, had ordered supplies sent to the port of Le Crotoy that lay far to the north, beyond both the Seine and the River Somme, but if the supplies were waiting then they were unreachable because the Seine was a wall behind which the English were penned in a land they had themselves emptied of food. The first horses began to go lame and men, their boots shredded by marching, went barefoot.

The English came closer to Paris, entering the wide lands that were the hunting grounds of the French kings. They took Philip’s lodges and stripped them of tapestries and plate, and it was while they hunted his royal deer that the French King sent Edward a formal offer of battle. It was the chivalrous thing to do, and it would, by God’s grace, end the harrowing of his farmlands. So Philip of Valois sent a bishop to the English, courteously suggesting that he would wait with his army south of Paris, and the English King graciously accepted the invitation and so the French marched their army through the city and arrayed it among the vineyards on a hillcrest by Bourg-la-Reine. They would make the English attack them there, forcing the archers and men-at-arms to struggle uphill into massed Genoese crossbows, and the French nobles estimated the value of the ransoms they would fetch for their prisoners.

The French battleline waited, but no sooner had Philip’s army settled in its positions than the English treacherously turned about and marched in the other direction, going to the town of Poissy where the bridge across the Seine had been destroyed and the town evacuated. A few French infantrymen, poor soldiers armed with spears and axes, had been left to guard the northern bank, but they could do nothing to stop the swarm of archers, carpenters and masons who used timbers ripped from the roofs of Poissy to make a new bridge on the fifteen broken piers of the old. It took two days to repair the bridge and the French were still waiting for their arranged battle among the ripening grapes at Bourg-la-Reine as the English crossed the Seine and started marching northwards. The devils had escaped the trap and were loose again.

It was at Poissy that Thomas, with Eleanor beside him, rejoined the army.

And it was there, by God’s grace, that the hard times began.

Eleanor had been apprehensive about joining the English army. ‘They won’t like me because I’m French,’ she said.

‘The army’s full of Frenchmen,’ Thomas had told her. ‘There are Gascons, Bretons, even some Normans, and half the women are French.’

‘The archers’ women?’ she asked, giving him a wry smile. ‘But they are not good women?’

‘Some are good, some are bad,’ Thomas said vaguely, ‘but you I shall make into a wife and everyone will know you’re special.’

If Eleanor was pleased she showed no sign, but they were now in the broken streets of Poissy, where a rearguard of English archers shouted at them to hurry. The makeshift bridge was about to be destroyed and the army’s laggards were being chivvied across its planks. The bridge had no parapets and had been hurriedly made from whatever timbers the army had found in the abandoned town, and the uneven planking swayed, creaked and bent as Thomas and Eleanor led their horses onto the roadway. Eleanor’s palfrey became so scared of the uncertain footing that it refused to move until Thomas put a blindfold over its eyes and then, still shaking, it trod slowly and steadily across the planks, which had gaps between them through which Thomas could see the river sliding. They were among the last to cross. Some of the army’s wagons had been abandoned in Poissy, their loads distributed onto the hundreds of horses that had been captured south of the Seine.

Once the last stragglers had crossed the bridge the archers began hurling the planks into the river, breaking down the fragile link that had let the English escape across the river. Now, King Edward hoped, they would find new land to waste in the wide plains that lay between the Seine and the Somme and the three battles spread into the twenty-mile-wide line of the chevauchée and advanced northwards, camping that night just a short march from the river.

Thomas looked for the Prince of Wales’s troops while Eleanor tried to ignore the dirty, tattered and sun-browned archers, who looked more like outlaws than soldiers. They were supposed to be making their shelters for the coming night, but preferred to watch the women and call obscene invitations. ‘What are they saying?’ Eleanor asked Thomas.

‘That you are the most beautiful creature in all France,’ he said.

‘You lie,’ she said, then flinched as a man shouted at her. ‘Have they never seen a woman before?’

‘Not like you. They probably think you’re a princess.’

She scoffed at that, but was not displeased. There were, she saw, women everywhere. They gathered firewood while their men made the shelters and most, Eleanor noted, spoke French. ‘There will be many babies next year,’ she said.

‘True.’

‘They will go back to England?’ she asked.

‘Some, perhaps.’ Thomas was not really sure. ‘Or they’ll go to their garrisons in Gascony.’

‘If I marry you,’ she asked, ‘will I become English?’

‘Yes,’ Thomas said.

It was getting late and cooking fires were smoking across the stubble fields, though there was precious little to cook. Every pasture held a score of horses and Thomas knew they needed to rest, feed and water their own animals. He had asked many soldiers where the Prince of Wales’s men could be found, but one man said west, another east, so in the dusk Thomas simply turned their tired horses towards the nearest village for he did not know where else to go. The place was swarming with troops, but Thomas and Eleanor found a quiet enough spot in the corner of a field where Thomas made a fire while Eleanor, the black bow prominent on her shoulder to demonstrate that she belonged to the army, watered the horses in a stream. They cooked the last of their food and afterwards sat under the hedge and watched the stars brighten above a dark wood. Voices sounded from the village where some women were singing a French song and Eleanor crooned the words softly.

‘I remember my mother singing it to me,’ she said, plucking strands of grass that she wove into a small bracelet. ‘I was not his only bastard,’ she said ruefully. ‘There were two others I know of. One died when she was very small, and the other is now a soldier.’

‘He’s your brother.’

‘Half-brother.’ She shrugged. ‘I don’t know him. He went away.’ She put the bracelet on her thin wrist. ‘Why do you wear a dog’s paw?’ she asked.

‘Because I’m a fool,’ he said, ‘and mock God.’ That was the truth, he thought ruefully, and he pulled the dry paw hard to break its cord, then tossed it into the field. He did not really believe in St Guinefort; it was an affectation. A dog would not help him recover the lance, and that duty made him grimace, for the penance weighed on his conscience and soul.

‘Do you really mock God?’ Eleanor asked, worried.

‘No. But we jest about the things we fear.’

‘And you fear God?’

‘Of course,’ Thomas said, then stiffened because there had been a rustle in the hedge behind him and a cold blade was suddenly pressed against the back of his neck. The metal felt very sharp.

‘What we should do,’ a voice said, ‘is hang the bastard properly and take his woman. She’s pretty.’

‘She’s pretty,’ another man agreed, ‘but he ain’t good for anything.’

‘You bastards!’ Thomas said, turning to stare into two grinning faces. It was Jake and Sam. He did not believe it at first, just gazed for a while. ‘It is you! What are you doing here?’

Jake slashed at the hedge with his billhook, pushed through and gave Eleanor what he thought was a reassuring grin, though with his scarred face and crossed eyes he looked like something from a nightmare. ‘Charlie Blois got his face smacked,’ Jake said, ‘so Will brought us here to give the King of France a bloody nose. She your woman?’

‘She’s the Queen of bloody Sheba,’ Thomas said.

‘And the Countess is humping the Prince, I hear,’ Jake grinned. ‘Will saw you earlier, only you didn’t see us. Got your nose in the air. We heard you were dead.’

‘I nearly was.’

‘Will wants to see you.’

The thought of Will Skeat, of Jake and Sam, came as a vast relief to Thomas, for such men lived in a world far removed from dire prophecies, stolen lances and dark lords. He told Eleanor these men were his friends, his best friends, and that she could trust them, though she looked alarmed at the ironic cheer which greeted Thomas when they ducked into the village tavern. The archers put their hands at their throats and contorted their faces to imitate a hanged man while Will Skeat shook his head in mock despair.

‘God’s belly,’ he said, ‘but they can’t even hang you properly.’ He looked at Eleanor. ‘Another countess?’

‘The daughter of Sir Guillaume d’Evecque, knight of the sea and of the land,’ Thomas said, ‘and she’s called Eleanor.’